What was the American Revolution? The people who joined to carry it out had different views of what they had done. In 1787 Benjamin Rush, a Philadelphia physician and ardent patriot, reflected that “the war is over, but this is far from being the case with the American Revolution. On the contrary, nothing but the first act of the great drama is closed.” In 1818 Rush’s Massachusetts friend John Adams had another view. “What do we mean by the American Revolution?” he asked. “Do we mean the American war?” And he answered himself, “The Revolution was effected before the war commenced. The Revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people.” Historians have extended the time span in both directions to give the Revolution different meanings. Gordon Wood in The Radicalism of the American Revolution carried it forward to include the advent of Jacksonian democracy in the 1830s. Jon Butler carried it backward as far as 1680, in Becoming America: The Revolution Before 1776.

In these assessments, whatever the Revolution was, the war figured in it only incidentally, if at all: the Revolution took place in cultural, political, and social changes that began long before the war and continued long after. Now comes David Hackett Fischer with a book devoted to one campaign in the war as a “pivotal moment” not simply in the war but in American history. Fischer’s moment, he explains, was the product of a “web of contingency,” choices made at different times by different people, culminating in George Washington’s crossing of the Delaware River on December 26, 1776, and in the battles he fought during the next eight days at Trenton and Princeton. In a fascinating narrative of the moves and countermoves of American, British, and Hessian forces, Fischer persuades us that the war itself was the source of political and social developments that continue to this day. His mastery of the historian’s craft enables him to embody his argument in telling us what happened and who it happened to, taking care not to clog the story with lengthy didac-tic interruptions. He thus resuscitates Washington’s reputation as a field general and at the same time demonstrates his role in establishing an American way of warfare and in fixing the place of the military in the republic that the Revolution created.

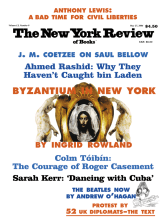

Fischer begins with a prologue devoted to the German-American painter Emmanuel Leutze’s commemorative depiction of Washington’s crossing, a huge painting, twelve feet high by twenty feet long, that has long been a target of ridicule. In it Washington stands proudly, right foot on a thwart, Bonaparte-like, in an overcrowded rowboat on the ice-filled Delaware. Surely he is about to tumble in. Actually, as we learn later, although the men manning the oars and paddles (one looks like a woman) seem to be sitting or crouching, most of those who made the crossing that night or any other time in the small river boats had to stand because those boats had no seats, and bilge filled the bottoms. The painting, Fischer argues, however faulty in minor factual details and whatever its artistic merits or lack of them, deserves the acclaim it received when first shown in Berlin in 1850. It faithfully portrays and celebrates the daring of the general and the leadership he brought at a critical time to ordinary people arrayed against the most powerful army in the world.

The other occupants of Washington’s boat are remnants of the Continental Army, badly bruised under his direction in their first pitched battle on Long Island in August, where they lost probably three hundred killed and over one thousand captured. Fatigue, disease, and desertion have plagued their lengthy retreat to the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware. Now, as the year draws to a close and their terms of enlistment expire, they are seemingly headed for dissolution as an army. Yet they are not behaving like men defeated. Washington still commands their loyalty as he stands precariously above them on their yet more precarious mission, striking back at the enemy that has mauled them so. “The painting,” Fischer tells us, “gives us some sense of the complex relations they had with one another, and also with their leader. To study them with their general is to understand what George Washington meant when he wrote, ‘A people unused to restraint must be led; they will not be drove.'”

Fischer has studied them, and he understands what Washington meant, understands it better perhaps than previous historians and biographers. He pulls no punches in describing Washington’s blunders on Long Island, but he demonstrates the success at Trenton and Princeton to have been achieved not by a stroke of luck but by brilliant military tactics. The usual accounts of those battles give us the garrison of Hessians, who had been brought to fight alongside the British, as dozing, drunk, and befuddled after a night of Yuletide revelry, and thus an easy prey. Fischer’s meticulous recovery of the facts from a multitude of diaries and official reports and correspondence shows the Hessians to have been exhausted but alert, exhausted, not from drink but from sleepless nights spent in fighting off continual raids by the New Jersey and Pennsylvania militias. For weeks they had been obliged to take their rest with the men of one whole regiment fully clothed, lying on their arms, and ready for battle. They were seasoned troops under experienced commanders, and they put up a fierce and skillful resistance in the streets of Trenton before they were forced to surrender. They were simply outfought and outgeneraled.

Advertisement

The Americans with Washington at Trenton, about 2,400 men, were probably even more exhausted than their opponents, after contending with the ice on the Delaware and making an eight-mile march through the night in a freezing Northeast storm. Two men actually froze to death on the march. After the battle it took the rest of the day and another day to get them and more than 800 prisoners back across the river to their camp in Pennsylvania. There they were joined by 1,800 militia from Philadelphia, eager to make another crossing and drive the enemy entirely from lower New Jersey. Washington and his weary men were up to the challenge. Most of them would complete the term of their enlistment in four days. They had earned not only rest but relief, a chance to go home alive. But when Washington asked for volunteers, most of them stepped forward, knowing only too well what they were doing.

By New Year’s Eve, they were back in Trenton, heavily reinforced by troops from as far as Virginia, but still outnumbered by the gathering host of British and Hessian regulars under Charles Cornwallis, the man whose final surrender Washington would accept nearly five years later. At Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781 Washington would trap Cornwallis between two rivers. Now Cornwallis tried but failed to trap Washington the same way. “One of [Howe’s] finest officers,” and later to be viceroy of India, Cornwallis was in Fischer’s estimate “a man of many talents and one of the most appealing figures of his generation.” Like Cornwallis, Washington was a commander who would not recklessly spend the lives of his troops, but he relished the warrior’s life. At twenty-two, writing to his brother in 1754, he had famously reported, “I can with truth assure you, I heard Bulletts whistle and believe me there was something charming in the sound.” Now, on the afternoon of January 2, 1777, Cornwallis marched 8,000 troops from their headquarters at Princeton and pinned Washington between the Delaware and one of its tributaries, Assunpink Creek. Cornwallis took heavy casualties that afternoon in repeated attempts to storm a small bridge on the Assunpink. He lost a total of 365 killed, wounded, and captured before darkness put an end to the battle.

In a council of war with his officers Cornwallis ordered a final full-scale assault the next morning, reportedly saying, “We’ve got the Old Fox safe now. We’ll go over and bag him in the morning.” But the Old Fox outwitted him. Leaving a few men to keep his campfires burning, Washington slipped away and marched his army by a roundabout route to Princeton, thinly defended after Cornwallis’s departure. There the Americans overcame the garrison in an early morning battle and retired from the town with their prisoners before Cornwallis, hurrying back from Trenton, could overwhelm them with his numbers. After two nights without sleep and two days of battle, the Americans withdrew to winter quarters at Morristown, and Cornwallis did not risk following. Looking back on the events six weeks later, a junior British officer confessed that Cornwallis, though a brave man, “allowed himself to be fairly outgeneralled by Washington.”

Washington’s victories, Fischer argues, were far more than symbolic. They were part of the strategy Washington had adopted after the Battle of Long Island: to avoid a general engagement (that would risk the loss of his only too volatile army) and to strike only when “a brilliant stroke could be made with any probability of success.” Trenton and Princeton were brilliant strokes: “The campaign that followed in 1777 might have had a different outcome if the British and Hessian regiments had not lost so many of their best troops before it began.” Fischer gives full credit to the professional skills and discipline of those troops and reconstructs the maneuvers of both sides with extraordinarily clear maps of every engagement. His appraisal of the enemy’s well-executed defense serves to magnify the success of Washington’s daring attacks. Dining with Washington after surrendering at Yorktown, Cornwallis generously toasted his adversary with the words, “Fame will gather your brightest laurels rather from the banks of the Delaware than from those of the Chesapeake.”

Advertisement

But what makes that success remarkable is not merely the tactical skills Washington had learned since the Battle of Long Island but the skills he had also learned in leading men who would not be drove. Washington wanted a disciplined, orderly army, and he often sounds like a martinet in his demands that everyone toe the line. He had a poor opinion of militia. But he learned to make the most of the fact that the men he led were often militia and that even the soldiers of his Continental Army regarded their service as contractual. They could rightly depart when they thought their contracts had expired. Soldiers from one state might refuse to serve under officers from another. And Washington himself had to accept the terms of his own employment by a Continental Congress that felt entitled to discuss and decide strategy.

The war was a learning experience for them all. Washington’s low opinion of militia did not blind him to the opportunity the Philadelphia militia presented him and his regulars when they returned on December 27 from their victory at Trenton. He embraced the militia’s proposal and led them with him through the Second Battle of Trenton and the Battle of Princeton, where he did not hesitate to call them “brave fellows,” assuring them that “there is but a handful of the enemy, and we will have them directly.” Washington personally led a detachment into action against British regulars, conspicuously mounted on a white horse, which prompted an American witness to record, in the high-flown language of the time, “I saw him brave all the dangers of the field and his important life hanging as it were by a single hair with a thousand deaths flying around him.”

As the war went on and other brave fellows enlisted in his army for longer periods and even for the duration, it came to look more the way Washington thought any army should. And Congress learned to keep hands off his operations. Two weeks before the famous crossing, Congress passed a resolution that “until Congress shall otherwise order, General Washington be possessed of full power to order and direct all things relative to the department, and the operations of war.” It was not a blank check. As Fischer emphasizes, both Washington and Congress insisted on “the principle of civil supremacy over the military.” Together they “created a new system that combined energy in government with republican institutions on a continental scale.”

Washington’s success at Trenton and Princeton bought time for republican institutions on a continental scale to develop and mature, eventuating in the Articles of Confederation and then in the federal Constitution. More immediately his success justified him in conducting the war as what it was declared to be, a defense of human rights. The enemy displayed the same contempt for those rights that the British ministry had. The “ministerial troops,” as Washington called them, were often encouraged by their British and Hessian officers to take no prisoners. After the Battle of Long Island an English officer observed that “the Hessians and our brave Highlanders gave no quarters, and it was a fine sight to see with what alacrity they despatched the rebels with their Bayonets, after we had surrounded them so that they could not resist.” At the Battle of Princeton “wounded Americans were denied quarter and murdered by British infantry, with their officers looking on.”

Washington did not countenance this kind of warfare. All wars beget atrocities, but as Fischer emphasizes, Washington “often reminded his men that they were an army of liberty and freedom, and the rights for which they were fighting should extend even to their enemies.” He did his best to see to it that his prisoners of war were treated more humanely than the Americans, who suffered starvation and disease in British prison ships. To the officer he placed in charge of 211 prisoners taken at Princeton he gave orders to “treat them with humanity, and let them have no reason to Complain of our Copying the brutal example of the British army in their Treatment of our unfortunate brethren.” After the war, over three thousand Hessian soldiers elected to remain in a country where they enjoyed rights denied them at home.

Washington had his own ideas about what the Revolution was. He had no hand in composing the Declaration of Independence, but he required his officers to assemble their men and read it to them “with an audible voice.” It was, he said, an assertion of “the Claims of the Colonies to the Rights of Humanity.” He and his men had fought the war from April 1775 to July 1776 in defense of rights claimed under the British constitution. The Declaration defined and affirmed those rights as belonging to all humanity. If the Revolution continued beyond the surrender of the British army at Yorktown, it continued as a fulfillment of the Declaration’s commitment to human rights. The rest of American history has been punctuated by movements to expand the definition of those rights and of the humanity that entitles them.

Washington and his contemporaries have often been faulted for not expanding the definitions fast enough, but Washington made a beginning by recognizing the humanity of his enemies in battle. The recognition could not have come easily when the enemy’s inhumanity invited retaliation in kind. It was indeed a pivotal moment when Washington made the war itself an example of what the Revolution meant and what it bequeathed to the nation it created. That heritage endures. It is violated whenever we fail to recognize our enemies’ humanity and deny them the rights that we fight to protect.

This Issue

May 27, 2004