1.

No tyrannical father presiding over an intimidated household was ever tiptoed around with greater caution than is the figure of President George W. Bush in the Senate Intelligence Committee’s fat report of its investigation into the scary stories about Saddam Hussein’s weapons of mass destruction cited by the President as all the justification he needed for going to war in Iraq.

Before the war the CIA expressed “high confidence” that once American soldiers had the run of Iraq they would find stockpiles of chemical and biological weapons, mobile laboratories to make more, vigorous programs to buy uranium and develop atomic bombs, and much else confronting the United States with a “gathering threat” or “growing danger”—words used by the President and other high administration officials to summarize the intelligence laid out in a National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) issued by the CIA on October 1, 2002. Only a week later the dangers described in the NIE convinced Congress to vote for war, and in March 2003 President Bush ordered an invasion of Iraq to remove those dangers once and for all. There would have been no Senate investigation and no report if the weapons had been found—indeed, almost any one of them would have satisfied—but a year of looking has turned up nothing.

It is presidents, not secret intelligence organizations, who decide if and when the United States shall go to war, but that fact was set aside, perhaps only temporarily, by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence at the outset of its investigation into the CIA’s embarrassing failure to be right about almost anything when it came to Iraq. It is unlikely that most Americans grasp the magnitude of the failure even now, but plenty of others around the world see it only too plainly. France, Germany, and Russia all resisted the American insistence on war in the Security Council of the United Nations, arguing that UN inspectors should be given additional weeks or months to continue their search for these weapons of mass destruction before war could be justified.

American officials and private citizens alike derided their concerns, ascribing them to naiveté, greed, or hatred of America. France in particular was held up to scorn. In the eighteen months since the invasion no one representing the United States—certainly not the President—has apologized for the administration’s arrogant insistence that it knew best, or even granted that in retrospect the French, the Germans, and the Russians might have had a point. But those who were proved right—Chirac, Schröder, and Putin—have said nothing triumphant or wounding about the weapons that weren’t there, perhaps because they share the Senate Intelligence Committee’s cautious restraint when it comes to the office of the President of the United States. More time for inspections might have allowed passions to cool, but the President was impatient, he was tired of “swatting flies,” as National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice later told the 9/11 Commission; and he put the presidential thumb on the scales for war.

Leaving out the President himself has become something of a pattern. The report of the 9/11 Commission, also released in July, is equally circumspect. The names of President Bush and his chief advisers are frequently mentioned, but the idea that the President himself might or should have done something to prevent the terrorist attacks of September 11 is not directly addressed.1 About as close to actual criticism as the commissioners were willing to go is the flat remark that despite numerous warnings from the CIA, America’s

domestic agencies never mobilized in response to the threat. They did not have direction, and did not have a plan to institute. The borders were not hardened. Transportations systems were not fortified. Electronic surveillance was not targeted against a domestic threat. State and local law enforcement were not marshaled to augment the FBI’s efforts. The public was not warned.

These things that were not done must have been not done by somebody, but that somebody, and the somebodies reporting to him, are not criticized by name, although knowledgeable readers who closely read the text get the drift easily enough. The Senate Intelligence Committee has gone the 9/11 Commission one better, barely mentioning the White House or its chief occupant at all. If presidents bear some responsibility for the performance of the directors of central intelligence who report to them, you won’t find it in the Senate report on the CIA’s biggest misreading of what would be found when the troops went in since it assured President John F. Kennedy in 1961 that rebel guerrillas would be met on the beaches at the Bay of Pigs by wildly cheering Cubans eager to be freed of Castro. Not even the Democratic nominee for president, Senator John Kerry, seems ready to say plainly that this immense mistake—the bloody invasion of Iraq to end threats which have turned out to be entirely imaginary—must properly be tracked to the door of the White House. Virtually all commentators in public office, Kerry included, prefer to linger on the “intelligence failure” itself—the CIA’s hundred-page NIE, wrong in almost every particular, and most dramatically about those in which it expressed “high confidence.”

Advertisement

But it is too soon for President Bush to hazard a sigh of relief, because the committee plans a second report, to be completed next year, which will address additional questions including “whether public statements, reports, and testimony regarding Iraq by US Government officials…were substantiated by intelligence information.” Put another way, the question is whether the President and his chief advisers in the run-up to war exaggerated, misrepresented, or ran on beyond the intelligence claims now shown to have been wrong.

There can be little doubt that the outcome of the election in November will affect the tone, perhaps even the conclusions themselves, in this “second phase” of the committee’s work. But in going about its work the Senate Intelligence Committee has laid the ground carefully for tough questions to follow, by choosing an unexpectedly narrow question to begin: Did the findings of the CIA in the National Intelligence Estimate of October 2002 rise plausibly from the evidence the agency had to work with? The temptation to score cheap points by matching up predicted stockpiles with the empty warehouses actually found has been firmly resisted by the committee. The estimate is treated on the CIA’s own professional terms: Were they wrong but reasonable in their assessments, or did they have to stretch the evidence to be wrong? In almost every case the Senate investigators tell us that the findings—those “high confidence” predictions about what Saddam Hussein had or was trying to get—did not reflect the evidence.

The basic sin came in many varieties—ignoring evidence, misrepresenting evidence, exaggerating evidence, overstating the evidence, going beyond the evidence, interpreting some evidence as strong when it was weak, sometimes even reaching conclusions without any real evidence at all. The report reaches 117 separate conclusions about the October 2002 NIE and other matters relating to prewar intelligence about Iraq, and it is fair to say that almost every one contains a more or less stinging rebuke of the CIA. The report does not say, but unmistakably implies with persuasive detail, that the exaggerations, overstatements, and misreadings of the CIA’s estimate writers all fail in one direction—describing Iraq as more dangerous than it really was.

Now why was that? you ask. The committee did too. A year ago the chairman, Senator Pat Roberts, said he was “concerned by the number of anonymous officials that have been speaking to the press alleging that they were pressured by Administration officials to skew their analysis, a most serious charge and allegation that must be cleared up.” In a secret committee hearing with leading intelligence officials on June 19 of last year, Roberts repeated his concerns and asked for help:

Did any of you ever feel pres-sure or influence to make your judgement…conform to the policies of this or previous administrations? The second part of that is, has any analyst come to you or expressed to you that he or she felt pressure to alter any assessment of intelligence? And finally, if you did feel pressure or were informed that someone else felt pressure, were any intelligence assessments changed as a result of that pressure?

Even before the war Washington was afloat in rumors that intelligence about Iraq was being skewed, but details were hard to pin down. Late last year the journalist James Bamford, best known for his books about the National Security Agency, was told by a CIA officer working on intelligence about Iraqi WMDs that “I never saw anything” proving Saddam had or was developing weapons of mass destruction, and “no one else there did either.”2 Office wisdom within the agency said the cupboard was bare. But in late 2002, while UN inspectors were reporting from Iraq that they had found no prohibited weapons or programs, the administration was pushing hard to build its case that Saddam’s WMDs were reason for war.

On December 21, according to Bob Woodward in his recent book Plan of Attack, George Tenet arrived at the White House with John McLaughlin, a career intelligence analyst who had risen to become the CIA’s deputy director, to outline the case for WMDs. It was a briefing in the classic mode of the sort sometimes called a dog and pony show—slides and flip charts about missile payloads and ranges; reports of bulldozer activity that suggested efforts to hide chemical or biological weapons programs; an elegant technical argument proving that Saddam was flight-testing an unmanned aerial vehicle with a range three times the distance permitted under UN rules; defector reports about mobile laboratories that could be used to brew up terrible diseases; recordings of Iraqi military officers apparently engaged in efforts to hide things from UN inspectors.

Advertisement

Many of the charges outlined by McLaughlin were later cited by Secretary of State Colin Powell in his speech to the United Nations on February 5, 2003, laying out the administration’s case for war. But Powell, who got mainly rave notices at the time, evidently has a gift for expression not shared by McLaughlin. At the White House briefing on December 21 the President was unimpressed. “This is the best we’ve got?” Bush asked Tenet, according to Woodward. “George, how confident are you?” “Don’t worry,” said Tenet, in a remark widely quoted, “it’s a slam dunk.”

Exactly what Tenet intended to convey by that remark is unknown; he has declined to own or deny it. But the effect was a whirlwind shaking of the cupboard in the CIA office charged with tracking Saddam’s WMDs, the Weapons Intelligence, Nonproliferation and Arms Control Center, referred to by its acronym, WINPAC. It was in this office that Bamford’s informant worked at the turn of the year 2002–2003. In January the informant’s boss at WINPAC convened about fifty people in a meeting to bolster the case for WMDs, described by Bamford in his new book, A Pretext for War. “And he said, ‘You know what—if Bush wants to go to war, it’s your job to give him a reason to do so.'”

Thoroughly disgusted, Bamford’s informant quit WINPAC but moved on to another intelligence office where he continues to do roughly the same work. It is probable that Senator Pat Roberts’s invitation to whistle-blowers reached the ears of Bamford’s informant but he did not choose to repeat to the Senate Intelligence Committee the marching orders issued by his boss at WINPAC. In his testimony, Jami Miscik, the agency’s chief of intelligence analysis, admitted there was a lot of interaction of CIA officials with policymakers, including Vice President Dick Cheney “coming back to certain points or issues repeatedly….” Cheney crossed the Potomac to discuss WMDs at the CIA as many as eight times in the year before the war, and Miscik conceded that an analyst pressed to go over and over some point about Saddam’s nuclear weapons program, say, “might be able to say or might think of that as some sort of, if not pressure, then some sort of a reluctance to accept the answer they were given….”

But was there outright pressure to change an assessment? No one claimed anything quite like that, despite a platoon of witnesses asked to identify anything—anything—that smacked of White House pressure. In its report the committee quoted eight analysts who went beyond the typical “no” or “never” when they were asked about pressure from on high. Among their comments:

? “…It might be that our assessments suited what they needed. But we were never pressured to make an assessment a certain way or anything.” (Biological weapons analyst at the CIA.)

? “I did not have any analysts come to me [to say] they were feeling pressure to change their judgments…as far as I’m concerned, there were no such things happening.” (National intelligence officer for science and technology at the CIA.)

? “We had no internal or external influences on what [the analysts’] judgments were.” (Chief of programs on nuclear weapons at the Defense Intelligence Agency.)

? “I think the NIE…was a rushed process like we talked about, but as it stands our position is adequately represented in there.” (Nuclear weapons analyst at the Department of Energy.)

About as close to charges of actual skewing as the committee could find came from two former intelligence officials, Gregory Thielmann, who left his position as head of the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR) shortly before the NIE was written, and Richard Kerr, a retired CIA official called back by Tenet to review the Iraqi WMD intelligence once it was clear the inspectors had come up empty. Kerr said that some CIA analysts had complained of the repeated questions from White House and other high officials, but in his opinion “nobody changed a judgment” and in any event “it is not at all unusual for analysts to feel they are being pushed by one group or another.” Not even Gregory Thielmann, who had publicly criticized the Bush administration for building its case on “faith-based intelligence,” said he could provide the names of specific analysts who had altered specific assessments under pressure. In its report the committee said it “did not find any evidence” that Cheney or other administration officials tried to coerce analysts.

I am not surprised. Asking CIA analysts if they have been cooking the books while their bosses sit in the room reminds me of those well-meaning Western lefties who paid visits in the 1930s to prisoners in the Soviet gulag and returned with assurances that the prisoners all agreed the food was great and they were getting plenty of outdoor exercise. Understanding how the CIA came up with its “high confidence” NIE requires the Senate to connect the dots, but it shouldn’t be hard. There are only two—the White House and the CIA. Which way does the committee think the influence runs? But the Senate Intelligence Committee has declined to hazard a guess on this point, and its careful wording amounts at best to a Scotch verdict—not proven. But the rest of the report, with its numerous examples and close analysis of evidence used to build a case for war, raises troubling questions about the CIA’s ability to dig in its heels when a president insists that a grab bag of ambiguous information is all he needs to prove a “gathering threat” or a “growing danger.”

2.

The one danger that trumped all others was the atomic bomb—“the smoking gun that could come in the form of a mushroom cloud,” as Bush put it in a speech in Ohio on October 7, 2002. That turn of phrase has an interesting history recounted by Bamford in A Pretext for War and by Michael Massing in these pages.3 It first appeared in a story by Judith Miller and Michael Gordon in The New York Times on Sunday, September 8, a month before the President’s speech in Ohio. Miller and Gordon reported that Saddam Hussein’s Iraq “has stepped up its quest for nuclear weapons,” a claim proved by its efforts to buy “specially designed aluminum tubes, which American officials believe were intended as components of centrifuges to enrich uranium.” One official was quoted anonymously as saying that “the first sign of a ‘smoking gun’…may be a mushroom cloud.” As it happened Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, Vice President Dick Cheney, and National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice all appeared that Sunday on talk shows to warn of the very danger that Miller and Gorden had reported—Saddam with a bomb. “We don’t want the smoking gun to be a mushroom cloud,” said Rice on CNN.

The President’s Ohio speech came a week after the CIA published its NIE, formally titled Iraq’s Continuing Program for Weapons of Mass Destruction. If Bush had sound reason to warn of mushroom clouds he must have found it in the NIE. Accordingly, the Senate Intelligence Committee devoted 106 pages of its 529-page report to the evidence provided by the CIA to back its “high confidence” that Iraq was “continuing and in some areas expanding” its nuclear program, that it could build a bomb “in months to a year” once it had the fissionable material, and that “we are not detecting” all of Iraq’s efforts to acquire nuclear weapons. Details aside, that roughly adds up to a claim that the prospect of Saddam armed with a bomb was definitely a “gathering threat.” What the Senate Intelligence Committee did was to ask whether the CIA and other intelligence organizations who contributed to the writing of the NIE actually had evidence to support their conclusions.

The heart of the agency’s case was built around four factual claims—that Iraq was trying to buy a kind of uranium ore called yellowcake in Niger; that Iraq was trying to buy thousands of aluminum tubes that could be used as rotors in a centrifuge to separate fissionable material; that magnets, high-speed balancing machines, and machine tools on the Iraqi shopping list were intended for its bomb program; and that Saddam himself was taking a personal interest in the program and in the community of scientists who were running it. In every case the Senate committee found that the evidence for these claims was thin or nonexistent, and it strongly suggested that the CIA’s analysts and estimate writers consistently ignored or dismissed evidence that undermined or contradicted their central claims.

The CIA’s bedrock assumption that Saddam never abandoned his hope of developing nuclear weapons can be traced back to the shock of discovering just how close he had come before the invasion of Kuwait in 1990. The cease-fire that ended the first Gulf War in early 1991 provided for open-ended inspections by the United Nations to confirm Saddam’s promise that he would shut down his weapons programs and destroy stockpiles of prohibited items. The Iraqi nuclear establishment that was discovered and dismantled during these inspections showed that Iraq might have been as little as a year away from producing a working atomic bomb. Saddam Hussein’s continuing defiance convinced the CIA and just about every other intelligence organization paying attention that Iraq might be down, in the WMD game, but it was not out.

The sanctions then imposed on Iraq made any all-out effort impossible but the CIA assumed that once the sanctions were ended Saddam would resume his race for a bomb. It was a reasonable assumption, just as it was reasonable to reconsider the assumption after the UN inspectors left Iraq in 1998 and conclude he wouldn’t wait till sanctions were removed—the inspectors’ departure offered Iraq all the freedom it needed to get going. But reasonable assumptions do not a proof make and the actual evidence assembled by the CIA and its rival in the Pentagon, the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), was in fact shaky, beginning with the CIA’s claim in the NIE that Iraq had been “vigorously trying to procure uranium ore and yellowcake.”

The case of the Niger yellowcake has already been explored in public, but the Senate Intelligence Committee adds significant detail to the story, stressing that the yellowcake was the only item on the Iraq shopping list that did not have a dual use—i.e., it could not be used for civilian as well as military purposes—thereby lending it additional strength as evidence. The report that Iraq had approached Niger to discuss a yellowcake purchase came originally from the British, but when the CIA sent former ambassador Joseph Wilson to Niger to check it out, he said that none of his contacts confirmed it. He added that the Niger uranium mines were operated by the French, and it would be all but impossible for five hundred tons of yellowcake to be diverted to Iraq.

Wilson’s report, according to the committee, was never circulated to the White House or cited in intelligence estimates; nor were later reports from a US diplomat in Niger discounting the yellowcake claim, and another State Department eyes-on check of a warehouse in which the US Navy had reported the yellowcake was being stored. The checker found only bales of cotton. Nevertheless, the British repeated the claim in a “white paper” issued on September 24, 2002, and an early draft of the President’s Ohio speech contained a reference, eventually dropped, to the yellowcake buy. An NSC staffer, according to the Senate’s report, initially resisted CIA advice to drop the claim because it would leave the British “flapping in the wind.” Even the CIA’s John Mclaughlin stepped back from the British white paper in a congressional hearing when he said, “I think they stretched a little bit” in pressing the yellowcake claim.

But the yellowcake story refused to die. A sheaf of fabricated documents arrived from Italy to muddy the waters in October 2002 and the President included the yellowcake story in his State of the Union address in Jan-uary—the soon-to-be-exploded sixteen words that “the British government has learned that Saddam Hussein recently sought significant quantities of uranium from Africa.” But despite the potential significance of the new documents, which purported to record the yellowcake deal, the CIA made little effort to obtain copies of their own, and when they did they were sluggish in checking them for authenticity despite a warning from the State Department’s INR saying they looked fishy.

Eventually the documents were shared with the International Atomic Energy Agency, which reported almost immediately that the documents were crude and obvious forgeries, a conclusion with which the CIA was subsequently compelled to sheepishly agree. This summary only sketches in lightly the many ways in which the CIA over a period of months demonstrated the faintest sort of desire to know whether Iraq was really trying to buy yellowcake or not. In favor of the story are vague rumors and unsubstantiated claims; against it were many specific denials, and yet this gossamer web of “evidence” was pumped up in the NIE to support a claim that Iraq was “vigorously” seeking new sources of uranium. The CIA did not make up or fabricate the yellowcake story, but the Senate report clearly shows, although it is too polite to say, that the agency estimators fabricated the “vigor” that was nailed on to give the claim weight and urgency.

The only other concrete things cited as evidence of Iraq’s determination to build nuclear weapons were the aluminum tubes which it was allegedly trying to buy, apparently from China. The tubes were real enough, and Iraq’s desire to buy them has not been questioned either. But what were the tubes for? On that question the Senate Committee found that intelligence estimators had divided into two camps—those (mainly in the CIA and DIA) who believed they were intended for use in a centrifuge, where over the course of a year they might be used to separate enough uranium-235 to make two atomic bombs; and those (mainly in the Department of Energy and the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research) who believed that the technical characteristics of the tubes, the history of Iraqi use of such tubes for missiles, and the Iraqi claims that the tubes were in fact intended for use in missiles all proved that the tubes, although prohibited by UN sanctions, were not part of Iraq’s nuclear program, if indeed it had one.

The Department of Energy in particular argued in great detail that the tubes were all wrong for uranium enrichment, and Iraq’s past efforts at a centrifuge program had followed a different path. One DOE analyst said, “We should just give them the tubes.” But the CIA ignored these doubts, sought “expert” advice backing the centrifuge interpretation from outside contractors who did not know enough to disagree, exaggerated the cost of the tubes, accepted a single flimsy claim that Saddam was “closely following” the tube purchase, falsely claimed that “almost every country” approached by Iraq to build the tubes said the tolerance specifications were too high, and while citing a DOE-INR “footnote” of disagreement in the text of the NIE, put the actual text of the footnote sixty pages deeper into the paper.

The committee’s report faults the CIA in every one of its twenty conclusions about analysis of Iraq’s nuclear program. It builds an argument for finding that the agency’s crafting and shaping of the NIE can only be described as an attempt to manufacture a case justifying war. But this case, if the committee should ultimately decide to dot the i’s and cross the t’s and state it plainly, must await the convening of a new Congress after November’s election.

But despite the committee’s reluctance to accept the logic of its own report, it is already clear that the agency’s false, exaggerated, and overstated claims set the stage for war. In December 2002 the CIA was asked to write an official evaluation of Iraq’s Currently Accurate, Full and Complete Disclosure of its weapons programs—a 12,000-page document delivered to the UN inspectors as required by the Security Council’s Resolution 1441, which sent inspectors back into Iraq and started the countdown to war. Woodward devotes a long section of Plan of Attack to the inclusion of this requirement in Resolution 1441. Vice President Dick Cheney argued that the Full and Complete Disclosure was the poisoned apple which would bring down Saddam Hussein, since he could never comply honestly with the demand. Either he would lie about what he had in late 2002, or he would admit he had been lying about WMDs for years past. “That would be sufficient cause to say he’s lied again,” Cheney said, according to Woodward, “he’s not come clean and you’d find material breach and away you’d go,” i.e., to war.

In the event the French successfully insisted on wording the resolution to say that a “material breach” would require a false declaration and a general failure to cooperate. But the distinction was empty; lies in the declaration, plus Iraqi failure to help the UN inspectors find the truth, would constitute the double-fault justifying war, and it was in that spirit that the CIA pounced on the Full and Complete Disclosure as soon as it was released by the Iraqi government in Baghdad on December 7. We learn from the Select Committee report that while WINPAC at the agency wrote the response, two analysts at INR and DOE, disgruntled at being shut out of the drafting process, exchanged complaints by e-mail. “It is most disturbing,” the DOE analyst wrote,

that WINPAC is essentially directing foreign policy in this matter. There are some very strong points to be made in respect to Iraq’s arrogant non-compliance with UN sanctions. However, when individuals attempt to convert those “strong statements” into the “knock out” punch, the Administration will ultimately look foolish—i.e., the tubes and Niger!

Now, nearly two years later, it is abundantly clear that the many claims made by the White House about “the tubes and Niger” were either substantially or completely wrong. But whether these errors were genuinely “foolish” depends on knowing what the false claims about Iraqi WMDs were intended to achieve. In October 2002 the claims were scary enough to win a vote by Congress for war. At the turn of the year they were used again to bolster the American case that Saddam couldn’t be trusted, and military action alone could solve the problem. The CIA-written US Analysis of Iraq’s Declaration was unequivocal: Saddam Hussein was defying the UN’s Resolution 1441 and was in noncompliance because Iraq in its declaration

fails to acknowledge or explain procurement of high specification aluminum tubes…[and] fails to acknowledge efforts to procure uranium from Niger….

The French, Germans, and Russians, as well as Hans Blix, continued to argue that the inspectors should be given more time, but no one came to the defense of Iraq’s Full and Complete Disclosure; no one said its “failure” to acknowledge current WMDs may well have been accurate. Wrong as they were, the CIA’s claims about Iraqi WMDs held up long enough to do what the President wanted—provide a reason for going to war.

3.

Americans are quick to criticize presidents for everything they don’t like, or want but don’t have, and at times they are willing to harass them so unmercifully on irrelevant personal grounds that presidents may be forgiven for regretting they were ever elected in the first place. But when it comes to the really big mistakes and disasters in public life, Americans can be strangely reluctant to hold presidents responsible. This reluctance can be seen plainly in discussion of the two recent intelligence failures—“catastrophic” in the words of a New York Times editorial on August 11—that are cited as the reason for fixing a badly broken system, the “failure” to predict and prevent the terrorist attacks of Sep-tember 11, 2001, and the “failure” in predicting discovery of Iraqi weapons programs that turned out to be imaginary.

George Tenet, before he retired as director of central intelligence, presided over both failures and is widely blamed for the faltering management that allowed them to happen, but while Tenet will have much to explain if he chooses to write a memoir, neither of these two failures can be usefully laid at his door. Consider first the report of the 9/11 Commission, which recounts in great detail the numerous ways in which the CIA and the FBI failed to grasp essential details and connections in the al-Qaeda plot to strike at America. There is a kind of agony in reliving the near misses by investigators who might have put it all together in time. Small wonder that the 9/11 Commission, and now Congress, are determined to oil the machinery so it will never happen again. But the 9/11 Commission also described in detail things that worked right, and no part of its report deserves closer scrutiny than Chapter Eight—“The System was Blinking Red”—which recounts the numerous warnings issued by the CIA in the year leading up to September 11.

“Warnings and indications” have always been the first priority of the CIA. The agency was created in 1947 specifically to prevent another disaster on the scale of Pearl Harbor, and its history can be read as a continuing saga of dangers spotted or missed—the successes so often, and fairly, described as unsung, and the failures which generate storms of criticism and typically leave the agency battered and gun-shy.

Throughout the cold war defectors and spies handled by the CIA were always asked first, before anything else, if they knew of any imminent threat to or attack planned against the United States. In the first half of 1961 none of the persons interrogated at the agency’s Defector Reception Center in Frankfurt, Germany, reported anything of the kind. Nor did they describe what many had seen—huge stockpiles of building materials in Berlin—because questions about such preparations weren’t high on the list. The result that summer was a painful and potentially dangerous surprise when the Soviet Union suddenly divided the city of Berlin with a wall—a huge construction project requiring vast stores of cinder block and barbed wire which the Soviets had accumulated under the agency’s eyes. Thereafter new questions were added to the debriefing of defectors, having to do with unusual East Bloc activities that might not appear threatening at first glance, but could provide clues to dangers around the next turn in the road.

During the hearings conducted by the 9/11 Commission Condoleezza Rice and other witnesses for the administration frequently said that the CIA never gave them a warning they could act on—a name, an address, an airline flight number, a city, a specific plan and time of attack. President Bush added that he would have moved heaven and earth to protect America if only someone had told him what needed to be done. But just how much detail did he really need? According to the 9/11 Commission’s report, before September 11 the Presidential Daily Brief (PDB) which the CIA delivered every morning to the White House included “more than 40” articles “related to Bin Laden.”

In March 2001 Richard Clarke, chief of the counterterrorism staff in the National Security Council, advised Rice against reopening Pennsylvania Avenue to traffic passing in front of the White House, warning that al-Qaeda cells were operating inside the United States and truck bombs were among their weapons of choice. In May the chief of the CIA’s Counter-Terrorism Center, Cofer Black, warned Rice that the threat level was close to the level it had reached during the millennium, when major plots were thwarted in Jordan and in the United States, including one targeted on Los Angeles International Airport. On June 25, Clarke cited six separate reports of al-Qaeda plotting; three days later he added that terrorist activity “had reached a crescendo.” At the same time the CIA was instructing all station chiefs to warn host governments around the world and to seek their help in disrupting terrorist cells. On June 30 an agency briefing was headlined “Bin Laden Planning High Profile Attacks.”

So it went, day after day, week after week. By late July, George Tenet told the commission, the threat level could not “get any worse”—“the system was blinking red.” This appears to have been the case in both senses. The collection efforts of the CIA and other organizations were not only bombarded with signs and reports of threatening activity, but the warning system itself—all those channels of communication intended to rouse the President and the White House staff to alarm and activity—was “blinking red.” This gale-force wind of warning reached its highest level on August 6, when the PDB delivered to President Bush on vacation in Texas was headlined “Bin Laden Determined to Strike in US.” For two years the White House fought to suppress the text of that warning and it is not hard to see why. It contains no addresses, dates, names of visa violators—no “actionable intelligence,” as Rice has frequently pleaded in the President’s defense. But the stark fact of Osama bin Laden’s desire to strike hard at the United States burns through unmistakably.

Hijacked planes, Osama’s knowledge of the millennium attack planned for Los Angeles airport, his patient planning for years before operations are carried out, the existence of seventy FBI field investigations of al-Qaeda activity inside the United States, even a reminder of the 1993 attack on the World Trade Center—it would be hard to imagine the system blinking red more vividly than it does in the PDB of August 6. One can imagine the terrible frustration of George Tenet over the following two years, criticized for “failing” to prevent the attacks on September 11, and forbidden by circumstance and loyalty to the President from bursting out with the obvious question—what more did he need?

But like the Senate Intelligence Committee, the 9/11 Commission stops there. Perhaps holding presidents accountable is more than any commission or Senate committee can fairly be asked to do; perhaps only the electorate can properly hold a president accountable. We shall see.

But it is clear that no attempt to fix the system can hope to succeed if it cannot or will not identify the part that is broken. Warnings are useless, if a president will not listen. No attempt to assess a foreign threat can hope to be accurate if the estimators answer directly to the White House, are in effect part of the president’s team, have been told unmistakably what the president wants, and know full well that their careers will flower or wither under his hot breath. Journalists and members of Congress know how this works; for the most part they went along as well.

The Senate Intelligence Committee will not deliver until next year its final verdict on the CIA’s National Intelligence Estimate used to justify war. It has stated in its July report that the estimate writers went beyond the intelligence they had to work with, and it will probably say as much about the President and other high officials who went further still in banging the drum—citing “gathering threats” and “growing dangers” that not even the most liberal of readings could find in the NIE. But taking the final step—stating plainly what is obvious to anyone who cares to see—may be more than the Senate Intelligence Committee, or any other group of official Americans, can bring itself to do.

The big idea on the table for fixing intelligence at the moment is the proposal, formally put by the 9/11 Commission, to establish a “national intelligence director” who will crack the whip when the dozen or so American intelligence organizations drag their feet, resist cooperation, insist on going their own way, cannot agree who is to run the spies, hold on to secrets too tightly or too loosely, or squabble over division of the immense, $30–40 billion American intelligence pie. This is a workable idea that will step on many toes but only one set of toes will really count. The Department of Defense may be expected to resist bitterly any loss of its control of intelligence budgeting, but it is ultimately presidents who will decide. President Bush has adopted the words but seeks to avoid the essence of the 9/11 Commission’s proposal; he would welcome a national intelligence director, but seeks to retain direct White House control of the director of central intelligence, who is the person who makes or breaks careers at the CIA, and ensures that the agency remains in effect an arm of the White House. It is that relationship—the intimate partnership between president and DCI—which explains why the CIA turned a miscellany of iffy intelligence reports into “high confidence” warnings of Iraqi WMDs.

If things had been otherwise, if the CIA had pressed and bullied the White House instead of the other way around, then the President would have lashed out angrily when the inspectors found nothing, and it became apparent that he had taken the nation to war without cause. But nothing of the kind happened. President Bush was serene. For a year he said those weapons might yet turn up, and Tenet loyally said the same. When others suggested something had gone badly wrong, the President expressed confidence in his director of central intelligence, just as he had following the attacks on September 11, and for the same reason. The country didn’t know it then, and the White House did what it could to keep the country from ever knowing, but for seven months George Tenet’s CIA had been hand-delivering warnings to the President about al-Qaeda at a rate of nearly two a week. Tenet might have volunteered one or two additional pieces of information—for example, the report he received on August 23 that FBI field agents in Minneapolis wanted to investigate an “Islamic extremist” arrested while learning to fly 747 airliners. Tenet says he told the White House nothing about that. It sounds odd, but that is what Tenet says. With that exception, Tenet’s performance as DCI was everything this president could ask for, and every word from Bush on the subject so far suggests that he agrees.

This is where things grow difficult for committees, commissioners, and ordinary citizens alike. It is not sympathy for President Bush as a person that makes them hesitate, but the power of the office of the presidency itself. A president is not only the leader of the country, but the leader of his party as well, and a serious attack on a president concerning a substantial matter is an invitation to conflict of a kind that resembles civil war. So the reason for the velvet gloves with which he is treated is not hard to understand. But the failure to act before September 11 and the unnecessary war with Iraq cannot fairly be blamed on intelligence organizations or anyone else. The White House is the problem, not for the first time. Iraq is President Bush’s war. He insisted on it, and nothing can save us from the same again until we find the will to hold the President responsible.

—August 25, 2004

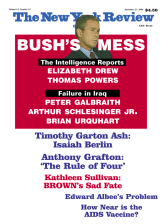

This Issue

September 23, 2004

-

1

See the review of the commission’s report by Elizabeth Drew in this issue of The New York Review.

↩ -

2

See Arthur Schlesinger’s review of his recent book, A Pretext for War, in this issue of The New York Review.

↩ -

3

“Now They Tell Us,” The New York Review, February 26, 2004.

↩