To the memory of Enzo Baldoni, an Italian journalist killed in Iraq on August 20, 2004

1.

On August 18, 2003, at the torrid end of the hottest summer in Italian history, the Italian critic Francesco Alberoni wrote on the front page of Corriere della Sera:

People today talk about health and food. They don’t read essays anymore that state problems they have to think about. Now we don’t think about the great thinkers. We no longer want to understand the process that produces our behavior, individual or social; we want formulas. Philosophers exist to answer questions. If no one asks anymore, they fall silent.*

Three months later, in mid-November, a loaded oil truck crashed into the Italian carabinieri station in Nasiriya, Iraq, smashing a way through for the car bomb that followed close behind it. Nineteen Italians and six Iraqis diedin the blast, and many others were wounded. Afterward Italians were no longer restricting their talk to health, food, TV, and the corruption of Silvio Berlusconi and his henchmen. They were asking the questions that Alberoni thought they would never ask again, most of which begin with “Why?”—questions of life and its eternal partner, death, which always intrude upon the party sooner or later. When they do, we suddenly rediscover the consolations of philosophy, art, literature, all the things that may look superfluous until normality veers off its safe, secure trajectory.

Horace said so somewhat playfully in a poem about spring, Odes IV.2, where he invokes melting snows and gentle breezes, ships being drawn down to the water’s edge, graceful nymphs dancing. Suddenly, abruptly, the announcement of pale death bursts on the scene in an explosion of p’s and heavy vowels: “Pallida Mors aequo pulsat pede pauperum tabernas regumque turris” (“Pale death pounds impartial the pauper’s door and kings’ towers”). Horace then addresses the friend he calls O lucky Sestius—O beate Sesti—to say that the short span of life forbids us to harbor long hopes. “Night,” he writes, “already presses down, the shades of the dead, the narrow home of Pluto”:

O beate Sesti, summa vitae brevis spem nos vetat incohare longam,

Iam te premet nox fabulaeque manes, et domus exilis Plutonia.

And that’s it. Watch out, Sestius, it won’t last forever.

The rebirth of spring, in the hands of Horace, already carries a shiver of winter, just as in a sketch by the Monty Python troupe when the Grim Reaper crashes a tony cocktail party after the salmon mousse turns toxic. “Oh do come in,” coos the hostess to the scythe-wielding guest, “make yourself at home.” She could almost be Emily Dickinson graciously conceding: “Because I could not stop for Death—He kindly stopped for me.” As if death were always so polite, so kind, so welcome!

In Nasiriya, and then in Istanbul, and in Baghdad, and many other places on our tortured planet, death has been no respecter of persons. Nor did the painter who frescoed the walls of Pisa’s medieval cemetery, the Campo Santo, in the years after the Black Death find it any more considerate. He showed the plague’s skeletal horsemen sweeping down on an aristocratic picnic, and they still do, even though an Allied bomber strafed the pure white marble and frescoed interior of the Campo Santo in 1944 and turned it into Dante’s Inferno. Time and again, the people we call upon to face the unfaceable are the artists, the poets, the novelists, the philosophers whose work may otherwise seem so impractical, so detached from the real business of life; the people who produce what for lack of a better word we today call culture.

The person who may have said it most concisely of all was Horace’s friend Vergil, the supreme poet of the early Roman Empire, in whose epic, the Aeneid, the hero looks at a painting of the sack of Troy and says about it simply: “Sunt lacrimae rerum et mentem mortalia tangunt” (“There are tears in things and mortality moves the mind”). As the fictitious painting touches the fictitious hero Aeneas, so the real Vergil touches us with the seething passions and somber duty of his twelve-part epic. And because that poem ends with a shocking eruption of brutality, when Aeneas kills the prisoner Turnus as he begs for his life, it may be that this single line about the “tears in things” in some sense summarizes the Aeneid’s whole tragic point. In his focus and his ruthless concision Vergil is a true heir to his model, Homer, who likewise, as my former colleague Herman Sinaiko used to say, “looks life in the face and doesn’t blink.” There are times when their unflinching vision is as close to understanding as we poor forkéd creatures can hope to get. They offer us no solutions, but they do offer us company, and the beautiful order of their poetry, to stand against the armies of a disorder that Vergil and Homer, at least, knew at first hand.

Advertisement

I took up my present job at the American Academy in Rome in September of 2001, stopping in New York on the way to Rome for a meeting scheduled for the morning of the 11th. I finally arrived in Rome nearly two weeks later, on a plane that flew out of Newark over the smoking crater on the end of Manhattan. With that vision in mind, and endless CNN images of planes ripping through steel, I spent the rest of that uncannily beautiful fall making an almost daily trek down the slopes of the Janiculum Hill to the Vatican Library. We all knew that the Vatican ranked high on al-Qaeda’s list of targets, but reckoned that they were more likely to take aim at the dome of St. Peter’s than the library’s warren of stacks and reading rooms, especially because a falling plane would take out a Koran or two among the other treasures.

Rome, like the poetry of Vergil, provided a strange solace. The city had seen it all before, several times over, enemies and barbarians knocking at the gates from Lars Porsenna’s Etruscans in 509 BC to the Gauls a century after, lured, it is said, by Etruscan wine and cowed by the dignity of the Roman senators. Rome had seen bloodbaths in the Forum before and after the dictatorship and death of Julius Caesar. The Visigothic invasion of AD 410, with furious fires that melted coins into the marble floor of the basilica Aemilia—still visible today—inspired Saint Augustine to write his City of God to explain, or try to explain, why such terrible things can happen.

The Normans came in 1054, fighting in the streets between the Palatine Hill and the Colosseum; a troop of German Landesknechte made two separate devastating raids in 1527; a French army allied with Pope Pius IX blasted its way through the Janiculum’s walls in 1849; and the Nazis seized the city in 1943. And yet for all that autumn of 2001, Rome sat gleaming in the sun, just as Central Park had basked that September in its golden Maxfield Parrish light under skies suddenly silent but for the military jets—or basked at least when the great pillar of smoke with its deathly smell turned away and drifted over Brooklyn.

But Rome and the Vatican Library provided more than their beauty and their eternity. On January 1, 1508, a rumpled academic from the university named Battista Casali gave a speech before Pope Julius II beneath the blue vault of the Sistine Chapel studded with gold stars—where in a few months Michelangelo would set up his scaffold to paint the ceiling we know today. Casali declared on that occasion that the greatest weapon against the Ottoman Turks, the era’s most aggressive superpower, was this same Vatican Library. He meant not only its copies of the Bible and the Church fathers, but also, and especially, its Greek and Latin classics, the works of Plato, Vergil, Plutarch, Horace, Sappho, Sophocles, Cicero, Aristotle, Vitruvius, the authors who exercised, instructed, and comforted the mind and soul. And despite the fact that Casali’s oration revolved around a clash between religions, he also meant the Arabic writers who had preserved Aristotle throughout the Middle Ages and invented algebra. Ottoman Turkey, as he well knew, was anything but a know-nothing Islamic state, and Islam in those days was no enemy of culture.

Casali found support for his position in what now might seem unlikely places. The Vatican Library’s most enthusiastic patron in 1508 was also the most important member of Casali’s audience: the Pope himself, Julius II, the Papa Terribile, the pope who sank as much money into the construction of St. Peter’s basilica, Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling, and Raphael’s frescoes as he did into his notorious military expeditions. And there is no question, five hundred years after Julius’s election in December 1503, about which investment, armies or art, has proven the shrewder.

One of Raphael’s paintings for Pope Julius took up a phrase from Casali’s 1508 oration and showed the Vatican Library as the School of Athens, with Plato, Aristotle, Epicurus, Socrates, Diogenes, Euclid, Ptolemy, and the Arab commentators congregating in the magnificent painted hall that once stood directly above the cupboards with their books. The School of Athens now stands above hordes of tourists.

German Landesknechte torched the book cupboards in 1527; Napoleon looted the Vatican Library in 1799 and carted much of it off to Paris. The barbarians at Rome’s gates have come in all shapes, sizes, and religions—or the lack of religion—but despite their efforts the Vatican Library abides, outfitted now with computers, a sleek new periodicals room, outlets for laptops at every desk, and a bomb shelter to protect the manuscripts against the next wave of Visigoths.

Advertisement

In September 2001, no one said that the best weapon against al-Qaeda was the New York Public Library. And yet Battista Casali’s point is as valid today as it was five hundred years ago. There is nothing more essential to us than what we carry in our minds. The Roman architect Vitruvius said so twice in his Ten Books on Architecture, and 1,500 years later, Pope Julius II was one of the readers who took note. In the preface to his Book Seven, Vitruvius declares that the most important possessions we have are the ones that can survive a shipwreck, and gives the example of a clever castaway washed up on the shore of Rhodes who, through his ingenuity, found friends, a job, wealth, and position in his new home. Abruptly, then Vitruvius says, “And so I thank my parents for giving me an education.”

True to these convictions, he begins his treatise on architecture by describing an educational curriculum for architects that includes drawing, mathematics, law, medicine, music, geometry, and astronomy among many other disciplines. He does not demand expertise, but he does demand competence, and his outline for an architect’s education circa 23 BC, passed on by manuscript after manuscript, generation after generation, remains one of the most passionate and influential briefs ever pleaded for the liberal arts. Vitruvius made his living at one point by outfitting catapults for Julius Caesar on the latter’s campaigns in Gaul. He therefore knew all the latest tricks of high technology, including the ancient Roman equivalent of weapons of mass destruction. The longest section of his treatise, the tenth of his Ten Books, is devoted to machines, the conveniences of peacetime, and the engines of war, on an escalating scale of technological sophistication. Yet at the climax of this military extravaganza, he tells the story of the siege of Rhodes, whose enemies, safely beyond shooting range, spend days assembling a huge siege tower, a multistoried platform on wheels, each level bristling with catapults, its snout a huge iron-capped battering ram.

On the night before the monster is to be dragged up to the Rhodian walls to smash its way to victory, a Rhodian architect gathers the citizens together and bids them to bring him full chamber pots, dishwater, bathwater, every kind of liquid, the fouler the better. He bores a hole through the city wall from the inside and through it pours the slops out onto the ground below. The next morning, when the giant war machine makes its way toward the walls of Rhodes, it meets a quagmire of redolent muck. As its massive wheels churn on and on, the behemoth sinks deeper and deeper into the ground, until it stops dead in its tracks well within range of the Rhodian archers, who dismantle it with the help of fire-tipped arrows and drag its carcass into the city; the invaders have slunk away. “Thus,” crows Vitruvius, “the best devices are undone by the cleverness of architects. When it comes to defense, don’t rely on machines. Instead, hone your strategies.” And there the book ends. The most marvelous machine of all, in Vitruvius’ book, is the human mind. A man who spent his life in the service of Roman technology and Roman conquest, who designed public buildings of impressive size and radical design, obviously saw his own life’s real essence, and that of his profession, embodied in our capacity to learn and think.

The greatest works of the imagination have an almost infinite capacity to communicate. Thucydides, for example, never ventures to distill anything so simple as a moral lesson from his scorching tale of folly, The Peloponnesian War. In it he famously shows how words change their meaning in wartime, warping the very basis of communication, and with communication, of principle itself. He has an Athenian delegation state the rules of realpolitik to the citizens of the little island of Melos, who appeal instead to their hope for justice. “Hope is desperation’s fairy tale,” say the Athenians, who then take the island, kill its men, and sell the women and children into slavery—the very Athenians who built the Parthenon, the Athenians of whom Thucydides’ Pericles once said, “We are the school of Hellas,” before the plague carried him off.

Thucydides, in his youth, had watched the tragedies of Aeschylus, Euripides, and above all Sophocles, with whom the great historian shares an incomparable sensitivity to the ways in which the placement of words can create, destroy, and reveal character. In a sovereign act of hubris, the Athenians decided in the year 415 BC to make war on Syracuse, the richest city in rich, remote Sicily. Thucydides describes the Athenian fleet sailing out in all its glittering pomp—I reread the description as US Blackhawk and Chinook helicopters set out for Iraq in the spring of 2003—but he has already described how large and wealthy Sicily is, and recounted the strange acts of religious vandalism that occurred the night before the fleet set forth.

He applies literary foreshadowing to the data of history, and the result is as magical as tragedy, a harrowing trip through euphoria to doom. As the ill-conceived expedition makes its progress toward total disaster, Thucydides carefully repeats, nearly verbatim, every feeble argument he once had the people of Melos venture to their pitiless Athenian conquerors, but this time it is the Athenian general, Nicias, racked by kidney stones, who tells his troops that, above all, they must keep up hope. Most of those soldiers, more desperate than hopeful, and crazed by thirst, will wade into the blood-choked waters of the river Assinarus, drinking down its polluted waters in ravenous gulps, before being hauled off to prison in the quarries of Syracuse. And there, Athenian legend has it, although Thucydides does not, the prisoners who could recite Euripides by heart were released, so eager were the Syracusans to hear the latest in Athenian theater. Vitruvius was not wrong about what survives a shipwreck.

Vitruvius’ advice does not necessarily mean that studying the classics automatically makes for better people. For centuries, if not millennia, the great authors have also nurtured a class of stuffy pedants. Take the case of Longolio, otherwise known as Christophe de Longeuil, a Flemish classicist whose expertise in Latin brought him to Rome to work for Pope Leo X in 1513. Longolio believed, with many of his contemporaries, that the best Latin had been the Latin of Cicero, and he strove to restrict his vocabulary and phrases to the vocabulary and phrases of the great Roman master, by that time 1,600 years dead. But because Cicero was an ancient Roman there were many things about which he had had nothing to say, including, most inconveniently for an employee of the Vatican, Christianity. Longolio was thus forced to call Pope Leo pontifex maximus, a pagan priesthood famously held by Julius Caesar, or “Jupiter the Thunderer.” He called nuns “vestal virgins” and the College of Cardinals the “Sacred Senate.” In the first century BC, there had been no churches, so Longolio called the places of Christian worship either “temples” or “basilicas.”

His worst problem was, as for so many academics, the jealousy of his colleagues. When the Pope let it be known in 1519 that he would grant Longolio honorary Roman citizenship, the Fleming’s Italian colleagues, as one in their resentment, dredged up an early oration that poor Longolio had given in Poitiers, where he had flattered his French audience by arguing that the French, not the Italians, were the true heirs to ancient Roman civilization. Brandishing the incriminating text, the Italians erected a tribunal on the Capitoline Hill and charged Longolio with a new crime they had invented for the occasion: Romanitas laesa, “injured Romanity.” But Longolio never appeared to take his medicine. Again in classic academic fashion, he ran away, to Venice, in fact, where he died from overwork attempting to defend himself using no phrase not previously used by Cicero. Partisans on both sides vented their outrage in letters to their Dutch friend Erasmus, who wrote back that as far as he was concerned they should be paying attention not to Longolio but to a man named Martin Luther, who had posted his ninety-five theses in Wittenberg two years before. Erasmus was right, of course. Today Longolio is virtually forgotten, and we praise those people who call a spade a spade and not a fodiator.

2.

The authors we still read today wrote in a way that ensured they would survive shipwreck because people remembered what they wrote, even the modest Vitruvius, who was much maligned by twentieth-century classicists as a terrible stylist, and who indeed apologized repeatedly for his deficient style to readers of his Ten Books. But one of the most perceptive of those readers, Petrarch, that fourteenth-century whirlwind of literary energy, said that Vitruvius had nothing to be ashamed of, and, given the overwhelmingly constructive influence that Vitruvius’ sometimes inelegant words have had on education, architecture, and civilized thought in general, Petrarch was surely right.

But I would also like to make an argument on behalf of authors whose immortality is not so obvious, like the writer who accompanied me in New York during the cataclysm of September 2001, in the science branch of the New York Public Library. His name was Father Athanasius Kircher, and he was born in the little German town of Geisa on May 2, 1602. If ever there has been a living Harry Potter, it must have been the young Athanasius, playing dumb in order to get by in Geisa, best known today for a local breed of thistle, a place where the curious boy went over the falls on a water mill when he tried to inspect its workings, survived a stampede of horses when he got too close to a racetrack, and where he learned firsthand what religious hatred could make people do to one another.

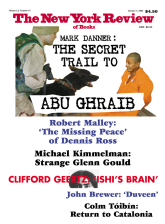

In 1669, Athanasius Kircher published a book called Ars Magna Sciendi (The Great Art of Knowing). The Ars Magna’s frontispiece (see illustration on page 32) was drawn carefully to follow the author’s instructions, and the professional book engravers of Amsterdam did mighty work transforming Kircher’s charmingly crude scrawls into impressive pictures, or, as Kircher called them, iconismi. Kircher took the book’s motto from Plato—it is written across the bottom of the Throne of Wisdom in Greek: μηδεν κα•?«λλιονη π•?«αντα ει’δεναι (“There is nothing more beautiful than knowing everything”). In other words, knowing everything was still a conceivable goal for a man like Kircher, who commanded twenty-three languages and claimed to have translated Egyptian hieroglyphs—and although he failed to do so to our satisfaction, he nonetheless provided Jean François Champollion, who did, with an essential key: namely, the idea that Coptic, the language of Egyptian Christians, descended directly from the language of the pharaohs. Champollion kept a copy of Kircher’s Coptic-Arabic-Latin dictionary beside him when he set to work on the Rosetta Stone, and we can still see this momentous volume with Champollion’s notes in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

Kircher was the first person to write about bioluminescence, the fire that lights up fireflies. He insisted that plague was spread by microbes before any microscope could yet see a bacillus of Yersinia pestis, and called for a quarantine in Rome when the disease struck in 1656. He created an early theory of plate tectonics to explain the presence of fossilized fish far from the sea. He suspected that the universe was infinitely large, evading the Inquisition by saying so not in a scholarly treatise but in one of the first science fiction books ever written, a book that, like all the very best science fiction, is also bitingly funny. Called Iter Exstaticum Coeleste (The Ecstatic Heavenly Journey) and first published in 1656, it features a sharp-tongued guardian angel named Cosmiel who flies a quaking Father Kircher through the universe, all the while making quips about Aristotle. The second edition of 1660 has a sequel that entrusts the earth’s watery regions to a runny-nosed little imp with a water-bucket, Hydriel, who plunges Kircher, among other adventures, into the belly of a whale.

The “Art” in Athanasius Kircher’s Great Art of Knowing referred specifically to a set of twenty-seven symbols, a system of Baroque hieroglyphs, by which Kircher hoped to express every aspect of human thought. Some of his categories still survive today in children’s games: animal, vegetable, and mineral, to which he added celestial, angelic, human, numerical, and several others besides; you can see them all arrayed on wisdom’s tablet like the Ten Commandments. His Jesuit colleagues could ostensibly use The Great Art of Knowing to convert the heathen to Christianity through this version of Esperanto in pictures. They were already hard at work in the seventeenth century trying to create a universal language of gesture—in Italy, especially—that could perform conversions without running into problems of translation. The sign language they evolved may not have worked among the heathen, but it worked wonders with deaf children in Jesuit schools, and now works wonders with deaf people everywhere; American Sign Language is its direct descendant. The hieroglyphic system of Kircher’s Great Art has developed into symbolic logic. But the Great Art itself entailed a good deal more.

Kircher’s frontispiece lays out the terrain of knowledge in images and written labels. Underneath the all-seeing eye of God, the eye within a triangle that also adorns our dollar bill, a scroll unfurls with fifteen seals, each naming a learned discipline. Below, Wisdom sits on her throne, between celestial bodies, with the sun blazing at the level of her heart (just where the head of Medusa once glowered on the breast of Minerva), holding the tablet with three rows of nine hieroglyphs, the symbolic alphabet of the Great Art. Below, a volcano spews lava into the air as a river erodes its slopes, flowing into the sea. The sea, in turn, devours the waters in a maelstrom. Divine wisdom abides above the clouds that mark off the supernal calm of Heaven from the realm of endless flux. Kircher, in effect, saw knowledge as moving in two directions: forward, with his own and his contemporaries’ increasingly fruitful investigations into the workings of nature, and backward, to a set of eternal truths. Each kind of investigation, to his mind, reinforced the other, and both endeavors were essential to the beauty of knowing everything.

It is more difficult in our own day than in Kircher’s to believe that we can know everything, let alone reduce that knowledge to one Great Art; indeed we have philosophers and scientists to tell us exactly how and why such a Great Art is impossible. Forty years ago, in the heady, hopeful atmosphere of the early 1960s, we might have put more faith in a Science of Knowing than an Art; in fact that process of shifting the center of cultural authority from art to science was already occurring in Athanasius Kircher’s day, to the point that the title Ars Magna Sciendi could almost be translated “The Great Art of Science.” Were Kircher transported to our new commodified twenty-first century, he would discover that knowing is neither art nor science; like everything else in our overdetermined lives, it has become a career. Still, he himself was no stranger to careers and marketing; The Great Art of Knowing was published by a Protestant press in Amsterdam as part of a comprehensive scheme to print all of Father Kircher’s forty-odd books in big editions loaded with pictures. They were, in effect, some of the first coffee-table books; as new and exotic as coffee itself, and like coffee they crossed every boundary of religion and culture. In Mexico, the seventeenth-century nun, scientist, and poet Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz made sure that her collection of Kircher books featured prominently in her portraits.

But what is the point of reading Athanasius Kircher today, now that even his most penetrating insights into science and Egyptology are long obsolete, the Great Art of Knowing proven philosophically impossible, the remarkable contortions by which he hid his true convictions from the Inquisition revealed for the twisted byways and dead ends they were meant to be? We have been taught for well over a century to believe that Galileo held the key to the future of the seventeenth century, whereas Kircher represented a step backward. So convinced of this fact were the unifiers of Italy in the late nineteenth cen-tury that they decided to break up Kircher’s Musaeum, still preserved up to that time in the halls of the Jesuits’ Roman College, where he had lived for over forty years until his death in 1680. Parts of his vast, strange collection, with its stuffed armadillo from Argentina whose lips curled in the process of desiccation, its Roman busts, Etruscan statues, fetal skele-ton, water organ, old master paintings, painted slate star charts, mastodon’s teeth, and Joseph Cornell–like boxes containing all of human knowledge on wooden tabs, were split up among a whole range of new national museums.

The move was seen as real progress in the 1870s. It looks now like yet another case of barbarism, barbarism brought on by long and understandable resentment of repression by the Catholic Church, but what did Athanasius Kircher have to do with Catholic repression? He struggled for free thought as valiantly, and also as deviously, as anyone in his time; it was sheer luck that the Protestant mercenary who once held a knife to his throat in the Thirty Years’ War let it drop when Kircher said, “I am a Catholic.”

Before the fruits of Kircher’s industry I feel rather like Saint Augustine in his Confessions at the moment when he and his friends raid a pear tree and start throwing the fruit at a pen of pigs. They weren’t very good pears, he starts out, they were proicienda ad porcis, and then he checks himself: “Who am I to judge, Lord? They were your pears. They were beautiful.” And Augustine is right; a pear, any pear, is a little miracle and wonderfully beautiful. It’s not the formulas that Atha-nasius Kircher arrived at that make him worth reading rather than throwing to the pigs, that make dismembering his Musaeum, the tangible expression of his Great Art, an act of vandalism that still yawns, in its own tiny way, like another Ground Zero of human ignorance. It is the fact that like the great thinkers whom Francesco Alberoni praised in the Corriere della Sera last summer, like the great authors I have cited here and the far greater number I have not, Athanasius Kircher was, and is, a builder of connections who insisted on seeing harmony in the midst of disorder. It may not seem to be much, but when gray clouds of death hovered in the air, and fire engines screamed outside the reading room where his ponderous old book opened onto a new century fully as terrifying as the three it had seen already, the Great Art of Knowing was great enough.

This Issue

October 7, 2004

-

*

Francesco Alberoni, “I filosofi tacciono perché la gente non ha più domande,” Corriere della Sera, August 18, 2003.

↩