To the Editors:

In his review of the report by the Union of Concerned Scientists on breaches by the Bush administration of scientific integrity [“Dishonesty in Science,” NYR, November 18, 2004], Richard Lewontin poses several questions to which I would like to respond on behalf of the UCS and the other scientists who signed the statement of February 2004 associated with the report. I do so because Lewontin’s disquisition, read by itself, has given readers I happen to know a somewhat inaccurate perception of the case made in both documents.

Lewontin asked, “Is elite knowledge to be given absolute priority?… How is the knowledge in the possession of the scientific elites to be factored into a process of decision in which considerations of economy, ideology, and political power also enter?” We have made it very clear at every opportunity that we as scientists understand fully that in a democracy only elected representatives can make ultimate political decisions, that such decisions inevitably involve factors other than scientific knowledge, and that such knowledge is rarely the dominant factor. Scientists have seen their input ignored or set aside by administrations of every stripe. Had the Bush administration only done that, there would have been no protest about misrepresentations of scientific knowledge in which astrophysicists expressed alarm about endangered species, ecologists about Iraq’s alu- minum tubes, molecular biologists about climate change, etc., etc. What provoked so many from so many disciplines to endorse the February statement (over five thousand have now done so, including forty-eight Nobel laureates) is that the administration, in the process of forming and advocating its public policies, has often breached the ethical code on which all the sciences are based.

Lewontin’s other questions were “Why should we trust scientists, who, after all, have their own political and economic agendas? On the other hand how can we decide by vote when the voters and their representatives have no understanding of the facts of nature?” Since 1945 the US government has developed an elaborate set of internal and advisory mechanisms that grapple with these questions, and which Lewontin described succinctly. On the whole, the political powers that be have allowed this system to function reasonably well, given the inherent difficulty of the task from both a technical and political perspective. While prior administrations of both parties have also harbored departures from ethical behavior in the use of these mechanisms, they were isolated events, whereas in the Bush administration purposeful tampering with the system has occurred repeatedly and in a large number of departments and agencies.

Kurt Gottfried

Union of Concerned Scientists

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Laboratory of Elementary Particle Physics

Cornell University

Ithaca, New York

To the Editors:

With respect to the accusation of scientific fraud by Robert Millikan repeated by Professor Lewontin in his review of H.F. Judson’s The Great Betrayal [NYR, November 18, 2004], it may be worth informing your readers of the article by David Goodstein “In Defense of Robert Andrews Millikan” in Engineering and Science, Vol. 63, No. 4 (2000), published by California Institute of Technology. Goodstein’s article in my opinion lays to rest this canard first presented as a case of fraud in 1982 by William Broad and Nicholas Wade, at the time reporters for Science magazine, in their book Betrayers of Truth.

Professor Lewontin writes, “Millikan’s measurements of the electrostatic charge on the electron were a classic case of discounting as aberrant the observations that did not fit well with his theory.”

Goodstein shows that they were in fact nothing of the kind, but rather the careful selection of those fifty-eight cases most likely to provide the greatest measurement accuracy out of the one hundred or so cases encountered over the sixty-three days of the experiment. Millikan’s 1913 result thus agrees with the value of the charge of the electron as measured today within the 0.2 percent uncertainty he was able to cite.

Goodstein’s article is all the more convincing that, together with photostats of extracts from Millikan’s notebooks and a good description of the experiment in question, it also gives the facts relative to and a balanced view of other accusations made against Millikan, of male chauvinism, anti-Semitism, and of mistreating his graduate students (in a special case of Judson’s “plagiarism”).

The complete article is available on the Internet at pr.caltech.edu/periodicals/EandS /articles/Millikan%20Feature.pdf and is well worth reading for the insight it gives into the human realities faced by scientists in their work as well as into their struggle with the hard facts of Nature.

Max Peltier

Lannion, France

To the Editors:

I am sorry that Richard Lewontin repeated without qualification the canard that Cyril Burt “invented fictitious collaborators” [NYR, November 18, 2004]. Your readers should be advised that the only evidence for this assertion is that Burt’s denigrators were unable to trace two female collaborators. It is well known that “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.” But in fact there is not absence of evidence. My father, Professor John Cohen, was a Ph.D. student of Burt’s in the 1930s. He recalled meeting one of these lady collaborators, and he mentioned this in an article in Encounter published at the time of the original brouhaha over Burt’s supposed fabrications. After my father’s death in 1985 I discovered relevant documentary evidence among his papers. There was a student handout on matrix algebra in which Burt acknowledged the assistance of Miss Conway. Burt’s denigrators have never come up with a motive for his supposed invention of collaborators. Anyone attempting this would have to explain why Burt felt it useful to invent a name to put on an obscure student handout written some twenty years before the publication of the papers in which these ladies’ names appeared. These ladies could well have been middle-aged in the 1930s, when the calculations for the student handout were made, and may have died long before the 1980s when various anti-Burt campaigners made vain attempts to verify their existence.

Advertisement

Detailed and balanced analysis of the case against Burt was published by Professor Ronald Fletcher in his book Science, Ideology and the Media: The Cyril Burt Scandal (Transaction, 1991). Professor Lewontin’s judgment that Burt’s apparent falsifications “were so transparent…as to suggest real pathology” is not a fair inference from undisputed facts.

Geoffrey Cohen

Rockville, Maryland

R.C. Lewontin replies:

We all owe a debt of gratitude to the Union of Concerned Scientists for their struggle to oppose the political misuse of scientific findings, especially at a time when truth seems not too highly prized by the state. I do not agree, however, with Kurt Gottfried’s answer to my question, “Why should we trust scientists, who, after all, have their own political and economic agendas?” Neither the UCS nor any state agency has grappled with the dishonest self-inflation that characterizes so much of the public utterance of scientists and their institutions, all in search of more self-esteem, status, and funding. In one form of this dishonesty, scientists say things with great authority that they do not know to be true. An example is the repeated assertion that the Human Genome Project will lead to a cure for cancer and a general increase in health and longevity. While asserting something one does not know to be true is not in itself a lie, there is an implication of authoritative knowledge which is certainly one form of falsification.

The other form of dishonesty, asserting something that scientists know not to be true, is literally a lie. An example is the statement, made over and over in various forms by biologists of the highest professional reputation, that genes determine us body and mind, whereas every biologist knows that the outcome of physical and mental development is the consequence of a contingent interaction between genes, environment, and random developmental events.

One result of the great emphasis that science places on scrupulous honesty is that any claim that a scientist is guilty of some intellectual hanky-panky generates a large volume of reexaminations and refutations. In addition to the letters sent to the editors of The New York Review, I have also directly received letters defending Burt, Pasteur, and Freud, and The New York Review long ago published a defense of Pasteur by Max Perutz.1 I am incompetent to comment on Freud. A great deal of the disagreement about Pasteur’s honesty hinges on whether the nineteenth century had different canons of professional ethics than are now considered the ideal. One thing is clear. Pasteur’s report that he prepared vaccine by exposure to the oxygen contained in air, while, in fact, he used a chemical, bichromate, to prepare it, was a falsification in light of the understanding of chemistry of Pasteur’s own time.

The matter of Robert Millikan raised in Peltier’s letter is more nuanced and illustrates beautifully the difficulty of deciding between dishonestly rejecting inconvenient observations and rejecting data from flawed experiments. Goodstein’s article cited by Peltier, although defensive of Millikan, leaves no doubt that the physicist went out of his way to hide the existence of inconvenient data.2 In reporting on the experimental oil drops Millikan wrote, “It is to be remarked, too, that this is not a select group of drops, but represents all the drops experimented upon during 60 consecutive days,” whereas from Millikan’s notebooks it appears that only fifty-eight out of 175 completed drop experiments were reported. The unreported drops were indeed of lower “accuracy” and more uncertain than the published result, and that is precisely the point. Millikan’s experiment had two purposes. One was to measure the unit charge on an electron, but the other was to refute the claim of the physicist Felix Ehrenhaft that there was not such a unit charge but that electrons were divisible into “subelectrons.” Because atomic physics was then in the process of establishing a model of a few indivisible elementary particles, this aspect of Millikan’s experiment was crucial.

Advertisement

The matter of Burt raised by Geoffrey Cohen is easier to deal with because of the variety of evidence of Burt’s dishonesty. Quite aside from whether Ms. Conway and Ms. Howard ever had any corporeal existence, it is undisputed, even by Burt’s defenders, that he published papers under a pseudonym when he was editor of the British Journal and that he put Conway as the sole author of another paper when she could have had no part in writing the paper, even if she existed. Moreover, Burt often did not state which twin pairs were included in which published reports, and he recorded educational attainment and physical attributes of supposed twin pairs, which data were invariant from study to study, even though different twin pairs were claimed to be involved. Such behavior disqualifies Burt from any serious consideration as an observer of the real world. My suggestion of a pathology was meant to be charitable. The alternative is to hold Burt responsible for conscious fraud in the service of what he regarded as a higher truth. But then, such behavior has become quite familiar to us in recent years.

There is an elementary confusion that arises repeatedly in considering fraud in scholarly life, a confusion between rigorous honesty on the one hand and correctness of a conclusion on the other. One may lie shamelessly about what one has observed yet be entirely correct in the claim being made about nature, and, of course, one may be rigorously honest yet reach an incorrect conclusion. Science, indeed scholarship in general, is a domain in which the integrity of the process is more important than the value of any particular result. This is not a question of an a priori ethic but of the very survival of the process of investigation. If science is not to be destroyed as a way of finding out about the world, the demand for honesty must be uncompromising and the fame awarded to those who have been right about nature must not be allowed to excuse or discount as unimportant any corruption of the process of which they have been guilty.

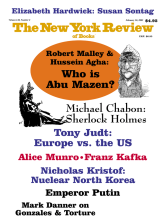

This Issue

February 10, 2005

-

1

M.F. Perutz, “The Pioneer Defended,” The New York Review, December 21, 1995. This was followed by an exchange between Perutz and William C. Summers, The New York Review, February 6, 1997.

↩ -

2

David Goodstein, “In Defense of Robert Andrews Millikan,” Engineering and Science, Vol. 63, No. 4 (2000), pp. 31–38.

↩