1.

With remarkable equanimity, we have since 2001 assimilated into our political metabolism a new Department of Homeland Security, complete with a presidentially appointed secretary, swarming bureaucracy, and enhanced budget. The department already occupies an important position in the Washington pecking order. On the other hand, it is not hard to identify a new executive department whose proposed creation would be met not with equanimity but with furious resistance from all sides: a Department of National Culture. Most Americans believe that their culture should grow out of the free marketplace of ideas, fashions, and institutions, not out of a state command system. Our knowledge of Nazism and Soviet communism has faded but not vanished. Fortunately one of the few books that inoculate us against totalitarianism, Orwell’s 1984, is still widely read in schools. We shall not soon have a secretary of culture.

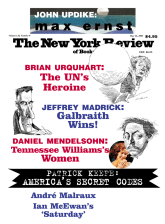

Fifty years ago we did indulge in a brief flirtation with a minister of culture—but not our own. The episode seems to belong in an earlier century. At the end of 1962, at the invitation of President Kennedy and of our fairy-tale first lady, and with the urging of President De Gaulle, the Resistance hero, celebrated novelist, and minister of culture André Malraux escorted Leonardo’s Mona Lisa from the Louvre to the United States. The painting traveled alone in its own first-class cabin aboard the liner Le France.1 It was exhibited in the National Gallery and in the Metropolitan Museum. All parties to the grandiose occasion, including the delighted press, conspired to turn it into a choreographed reaffirmation of marriage vows between France and the United States during a major cold war crisis in French–American relations. In photographs the event looks like a royal wedding.

But I suspect that many Americans would identify Malraux not as the diplomat of high culture but as the plain-spoken national custodian of everything French, who decided it was high time to give the façades of Paris public buildings a good scrubbing. When he did so, even the scoffers granted that it was a success.

Who, then, is this Malraux figure that we should honor him? Or perhaps mock him?

The first major entry in Malraux’s curriculum vitae landed the impecunious, fearless, twenty-three-year-old adventurer in front of a spiteful French colonial judge in Phnom Penh. Caught attempting to loot Khmer statues from a crumbling temple, Malraux spent six months under house arrest and received a three-year prison sentence for an offense that French colonial officials could commit with impunity. Malraux’s friends and supporters among Paris writers and intellectuals raised enough rumpus to have his sentence suspended and to bring him home. He soon returned to Indochina, where with a local lawyer he founded a hard-hitting anticolonialist newspaper. They wrote, edited, printed, and distributed the paper in Saigon from June to December 1925 in the face of bitter and sometimes violent opposition from colonial authorities. Malraux spent two and a half years in Indochina and returned to Paris at twenty-five with a contradictory notoriety as brazen thief and political hero. Could he survive this opening?

The following eight years through 1933 form the most intensely literary period of Malraux’s career. He became an editor and artistic director at the Gallimard publishing house. He and his German-born wife traveled widely, including a trip around the world. Most significantly, he wrote, revised, and published three major novels. The third and best of them, Man’s Fate (1933), based on the Chinese Communist revolution of 1927, won the prestigious Goncourt Prize and became a best seller in several languages.

Early in 1934, flush with his royalties and sponsored by a Paris newspaper, Malraux and a pilot friend made a daring four-week aerial foray to Yemen on the Red Sea. Their inflated but not baseless claims of having discovered from the air the buried ruins of the capital city of the Queen of Sheba catapulted the two explorers onto the front pages of European newspapers. Dismissed as an unprofessional escapade and welcomed as the discovery of a new aerial approach to archaeological exploration, the Yemen trip provoked controversy that continues to this day. The veteran and enthusiastic Malraux scholar Walter G. Langlois recently published a detailed narrative and reassessment of the Sheba expedition in the Revue André Malraux Review. Langlois credits Malraux not with intellectual exhibitionism but with love of bizarre adventures, of genuine personal risk, and of out-of-the-way research. With its Arabian desert backdrop, Langlois’s account provides a vivid portrait of Malraux in his thirties.

Malraux flew back to Paris in time to be swept up in fierce arguments over Trotsky’s banishment to France. After Malraux visited Trotsky in hiding, the Soviet exile devoted a long, generally favorable review to Malraux’s first novel, The Conquerors. Trotsky also advised Malraux to read Marx more carefully.

After 1934, Malraux became increasingly the spokesman for antifascist sentiments widely embraced by Communist Party members and sympathizers. Though he accepted an invitation to travel to Moscow to attend the First Soviet Writers Congress in 1934, he gave a passionate speech in favor of the independence of the writer to reject the new Party line of “socialist realism.” On the last day of the congress, Malraux proposed a show-stopping toast to Trotsky, Stalin’s fiercest enemy. Malraux never joined the Party. The prominent French author André Gide had also plunged into an intensely political period by 1935. One or both of the two writers seemed to preside over, or address, every major antifascist meeting, conference, parade, and rally in Paris until the outbreak of the Spanish civil war in 1936. That development changed the scene, the plot, and the cast of characters of left-wing politics in Europe.

Advertisement

Malraux felt no inclination to flee the looming war clouds and he remained in the thick of things. Without being a pilot himself, he organized and commanded the first Republican squadron of bombers and fighters (piloted by foreigners) in combat. The fruit of Malraux’s three tumultuous years in support of the Spanish Republicans was a tautly written war novel, Man’s Hope (1937), and a stunning semidocumentary film based on the novel’s closing scenes. After the fall of France to Nazi troops, Malraux was taken prisoner while serving in the Resistance under the name of Colonel Berger. He resumed his own name while commanding a sturdy brigade of French troops during the final campaign to retake Strasbourg. During his several years under arms, Malraux was wounded and decorated less frequently than some of his admirers claimed. Yet he displayed remarkable qualities of leadership and courage.

There was to be no intermission. After the liberation, Malraux distanced himself from left-wing causes and threw himself into writing, editing, speaking, and organizing for De Gaulle’s new political party. When De Gaulle finally came to power in 1958, he appointed Malraux to the important position of minister of culture, where he remained until De Gaulle’s entire government resigned in 1969. During that decade, Malraux carried out an ambitious program of conservation, education, cultural exchange, and encouraging the arts. He also found time for his own writing (on the arts and his memoirs), for editorial work for Gallimard, and for missions and trips to every continent. During ten relatively happy and healthy final years, Malraux maintained his program of writing, speaking, and travel. He was no malingerer.

I’m put in mind of a miniaturized version of Malraux’s life to be found in Jack Teagarden’s wistful vocal rendition of Ira Gershwin’s “Can’t Get Started” of the 1930s:

I’ve been around the world in a plane,

I’ve settled revolutions in Spain,

I’ve got a house, a showplace,

Still I can’t get no place

With you.

Women occupied a significant and troubled part of Malraux’s life, but getting started does not appear to have been a major obstacle.

It is difficult to give this Protean life a simple outline or to probe far enough into it to find key character traits. But the mass of documentation and controversy that heaps high around Malraux’s name yields two historic incidents and two oracular fictional scenes that seem more revealing than most other items.

Twice, riding on his fame as novelist, public figure, and adventurer and on the spellbinding power of his speeches, Malraux addressed an over-excited meeting of leftists in the immense auditorium of La Mutualité in Paris. Each time he struck an effective blow against the impending Communist takeover of the French left. In 1935, presiding with Gide in Paris over the First International Writers’ Congress in Defense of Culture, Malraux did not so much as mention the latest Party directive for writers: socialist realism. Gide’s and Malraux’s firmness prevented the congress from becoming primarily a front for Communist propaganda.2

Ten years later in the same Left Bank auditorium, representatives from war-time Resistance groups met to discuss whether or not to “fuse” into the Communist-run National Front. It was a crucial moment. Speakers raised their fists. Called back from the Alsace front where his brigade was deeply engaged in the liberation of Strasbourg, Malraux, in his colonel’s uniform with riding boots and insignia, provided the major voice in turning the vote against fusion and against further Soviet encroachment inside France. From this moment on, Malraux threw his unconditional support to General De Gaulle, who finally slowed the growth of the Communist Party in France. Malraux rarely failed to find the appropriate beau geste for an important public occasion.

Those who have read some of Malraux’s writings are probably familiar with the many oracular passages in his fiction. Two such moments strike me as particularly revealing. The central character in Man’s Fate, Kyo, a Communist organizer of mixed parentage in Shanghai just before the 1927 revolution, listens to a recording of an unfamiliar male voice. He is shocked to discover that it is his own voice. Told that this error often happens the first time, Kyo’s dismay over not recognizing himself is not dispelled by the information that we are accustomed to hearing ourselves not through the ear but through the throat. The sudden failure of (self)consciousness provoked by this little incident reinforces in Malraux’s universe the interior discrepancy that the teenage poet Rimbaud expressed through faulty syntax: Je est un autre (“I is another”). Kyo, Malraux, and Rimbaud are sailing close to the reef of solipsism. Neither action nor introspection will eliminate the peril of losing touch with oneself. Who is that out there? Or in here? There is ample reason to find Malraux’s fiction as metaphysical as it is psychological.

Advertisement

When, in his sixties, Malraux sat down to write his memoirs, he entitled them Antimemoirs and opened with a weighty conversation with a priest about death and confession. Melodramatically, “the priest raises his woodsman’s arm in the star-filled night” and pronounces the words that become the leitmotif of Antimemoirs, of many of Malraux’s other writings, and of his public career:

Et puis, le fond de tout, c’est qu’il n’y a pas de grandes personnes.

After all, the basis of everything is that there are no grown-ups (or great men).

The first version of grandes personnes, “grown-ups,” evokes the theme of the child that survives in many of us. The second version, “great men,” reaches beyond maturity and coming of age into the enigma of human greatness. Most debates about Malraux connect with one or both of these themes. Was there something immature about his most farfelu, or loony, projects? (He wanted to organize a posse to rescue Trotsky from Stalin. A few years later Malraux began organizing his own international relief mission to help those suffering in Bangladesh.) Does his attraction to great historic struggles such as the civil war in Spain, and to prominent figures such as the Kennedys, Mao, and De Gaulle, reveal an unsavory quest for human glory and greatness?

Those questions have elicited many answers. His close friend André Gide had reservations about Malraux’s writing and at the same time considered him a great man for his political courage and resourcefulness and for his real capacities as a leader. On the other hand, Olivier Todd, Camus’s biographer and author of the principal biography under review, has stated in many interviews that he values Malraux as a great twentieth-century novelist, but not as a great man in any nonliterary sense.

2.

Todd’s hefty volume, now translated into English, follows some seven earlier full-length biographies that appeared before and after Malraux’s death in 1976. In his preface to the most balanced of them, Curtis Cate points out that Malraux has been accused of three alleged betrayals or character flaws: he abandoned a fellow-traveling leftist political position for Gaullism; he repeatedly abandoned politics for literature in several forms; and his talents (as novelist, platform speaker, government minister, combat officer, and art critic) were just too varied to be credible. Having spotted these difficulties in his path, Cate went on to write an account of Malraux’s life, writings, and public career that stands up well today.

In the mid-nineties the “postmodern” philosopher and theorist Jean-François Lyotard published a freewheeling yet well-informed biography, Signed, Malraux. On the opening page, Lyotard, writing in the third person, projects himself into Malraux’s consciousness at age two, attending his older brother’s funeral: “…He felt that none of this agitation was real, that all was but decor….” Lyotard tries to tell (not to show) us too much too fast. In spite of its jumpiness and its attempt to offer us the inside story of every event, I find Lyotard’s book stimulating. It projects a strong awareness of the intensity both of the period between 1930 and 1970 in Europe and of Malraux’s long and historically important engagement in that period. Lyotard’s sometimes familiar yet forceful style owes a good deal to the writer he is examining.

In its length, comprehensiveness, and inclusion of new material, Todd’s recent biography can claim to add substantially to earlier accounts. It keeps Malraux’s life moving as a flickering series of expeditions—geographic, introspective, and ideological. Todd also intermittently reveals a low-keyed animus toward Malraux’s sustained virtuoso performances as hero in public and in private. In his opening pages Todd raises all the prickly questions about Malraux’s use of hyperbole, his loyalties, and his self-promotion. But by the end, after acknowledging Malraux’s literary standing as next to Hemingway and Orwell, Todd makes his most perceptive and most generous statement as a biographer:

I asked Paul Nothomb if Malraux had always been a compulsive liar.

“Absolutely, as an artist, as a creator…. But if you mean by that someone who ends up believing in the untrue things that he allows others to say about his life …then no…. He was playacting, but without ever, I am convinced, being fooled.”

I have my doubts about that. But the transpositions, myths, and metamorphoses that overlapped one another in his life were, on the whole, devoid of spite, malice, or pettiness.

Todd’s nagging doubts do not prevent him from welcoming the high national honor of transferring Malraux’s remains in 1996 to the Pantheon to join Rousseau’s. And Todd quotes without a quaver De Gaulle’s almost scriptural tribute to Malraux:

On my right, I have and will always have André Malraux. The presence at my side of this genius friend, this devotee of higher destinies, makes me feel that I am shielded from the commonplace. The idea that this incomparable witness has of me helps to make me strong. I know that in debate, when the subject is serious, his lightning judgment will help me disperse shadows.

The running debate in Todd’s biography on Malraux’s true stature as a historic figure keeps the book moving fairly briskly through a heavy undergrowth of incident and detail. As a rule, but not consistently, Todd chooses the historic present for his narrative. To my ear the present tense creates more thinness in his style than immediacy.

At intervals, a clumsy turn of phrase interrupts the narrative and distracts the reader. About the Malrauxs’ finances he writes, “The Mexican shares aren’t rising anymore. That’s worrying. They’re going down. Tiresome. What’s that? They’re not worth a penny? André and Clara Malraux are ruined.” Later Todd quotes one of Malraux’s early declarations of allegiance to De Gaulle: “France has at its head another man who has faith. I am sure of General De Gaulle. I am sure that he will fulfill his mission.” Todd cannot stifle a sneer. “Nice of Malraux to give the General a character reference.”

Todd tends to change his tone too abruptly. Often the translation is at fault. Joseph West falls too easily into the arms of a translator’s “false friends.” Procès yields “process” instead of “trial.” Devise yields “device” instead of “epigraph.” This sentence about Malraux near the end of his life moving in with an old and intimate friend is almost offensive:

Louise [de Vilmorin] has had a few husbands, and more than a few lovers. Now André Malraux, this grand figure, has shacked up in her life, then moved well and truly in.

West has dug up a slangy, pejorative verb in English that distorts the simplicity of the French verb camper. These stylistic soft spots are annoying. But between Todd and Cate Malraux has been well served in English.3

3.

Intellectually overendowed, self-educated in a large number of fields, thriving on extended periods of hard work, sociable enough to make several loyal, lifelong friends, celebrated as a writer, adventurer, and political figure, Malraux appeared larger than life to almost everyone who encountered him. Principally through his conversation, he dominated whatever scene he was a part of—except in the presence of De Gaulle. Where did this ability come from?

An astute caricaturist might well draw Malraux guided along his path by four exceptional early influences: Baudelaire, poet-dandy of modern urban life; Rimbaud, youthful revolutionary in poetic form; Nietzsche, who held up the man of action–philosopher as superior to ordinary men; and Lawrence of Arabia, the cultured Westerner who “went native” and created the exotic role of conqueror of the Middle East. This entourage of restless minds propelled Malraux to describe himself in extravagant and somewhat misty terms:

Just as the poet substitutes a new relationship for the relationship of words with one another, so does the adventurer attempt to substitute for the relationship of things with one another—for the “laws of life”—an unusual relationship. Adventure begins with a change of scene…; it is realism of the marvelous.4

The ambidextrous poet of words and of deeds maintained his central role throughout Malraux’s life. Langlois uses this quotation as an epigraph. In his novels as in his own life, Malraux keeps the intellectual hero and the man of action very close together. Many critics have pointed out how aptly Malraux’s fiction anticipates what we now refer to as existentialist “engagement.”

“The voice has played no small role in the history of literature.” These words from Malraux’s preface to Funeral Orations suggest his familiarity with the importance of public oral performance in Islamic culture, and his awareness of his personal prowess both as conversationalist and as formal orator. In her Paris Journal, Janet Flanner wrote a vivid description of the effect his speaking had on her in his prime:

He made what was undoubtedly the most exciting, excitable speech of the conference, feverishly kneading his hands, as is his platform habit, extinguishing his voice with passion and reviving it with gulps of water, and presenting an astonishing exposition of politico-aesthetics that seemed like fireworks shot from the head of a statue.

The best known of his orations (fortunately we have a recording of it) celebrates the Resistance hero Jean Moulin, who never cracked under torture. On a cold windy day in the courtyard of the Pantheon, Malraux de-livered a formulaic narrative tribute to Moulin in which every word rings clear. The cadenced classical delivery gradually lifted the audience to a level of emotion adequate to move them to belt out a resistance song at the end. Malraux had the makings of a demagogue.

Attracted as he was to public life and to the unfolding of historic events, Malraux did not playact in order to lay aside his own personage for a false one. It is tempting to associate him with a condition known in psychiatry as Histrionic Personality Disorder (HPD). The disorder is characterized by self-dramatization, attention-seeking, and a craving for novelty and ex-citement. However, Malraux lacked two important symptoms of HPD: difficulty in forming lasting friendships and lack of interest in intellectual achievement and analytic thinking. Despite his tics, his impulsiveness, and his excitability, Malraux is not best understood as suffering from a mental disorder. He accomplished too many major undertakings in his seventy-six years of writing and political action to be considered unbalanced or lunatic.

Rather this tireless participant in the momentous events of his time earned a prominent role in what many would call the great overarching saga of the twentieth century: The God That Failed. It was independent-minded figures such as De Gaulle, Malraux, and Gide who, between 1930 and 1970, blocked the advance of the Soviet experiment and the Communist Party in France. Olivier Todd’s biography sheds light not only on Malraux’s life but also on several decades at the turning point of contemporary history. Malraux’s two novels Man’s Fate and Man’s Hope have won a recognized place in European and world literature for their acute portrayal of political, intellectual, and personal life under deep stress. They enact the intensity of a decade when Western civilization was under attack from within, a decade when on certain wrenching occasions the audience could sing the Internationale and the Marseillaise with equal enthusiasm, and when hundreds of Eu-ropean athletes, lined up in stadiums, raised their right arms in what could be interpreted as either the Olympic salute or the Nazi salute. The path Malraux threaded through these parlous times was not straight and narrow. It was convoluted and immensely broad.

4.

What does it mean that Malraux’s longest stint at any one task lay in his ten consecutive years as minister of culture in De Gaulle’s Fifth Republic? Malraux established, following Soviet precedent, several Maisons de la Culture in France. He became a missionary for French culture on every continent. He made the major administrative, personnel, and artistic decisions in carrying out the government’s policy of subsidies for music, opera, theater, dance, and museums. At times, such as the Algerian crisis and the student riots of 1968, Malraux found himself plunged again into the cauldron of contemporary politics. Two fairly recent books that deal with cultural affairs in France take a close and critical look at Malraux’s service as minister of culture. Earlier studies devoted considerable space to pondering whether Malraux was a clever charlatan and court jester of genius, or whether he was an astute political player who served himself well and his country even better.

The two later books take up a different debate. A distinguished historian of the Renaissance at the Collège de France, Marc Fumaroli, published in 1991 L’État culturel: Une religion moderne (The Culture State: Essay on a Modern Religion). As the subtitle implies, the book is as polemical as it is historical. Far from being the natural product of a society, Fumaroli argues, “Culture is another name for propaganda.” He picks up the point near the end. “There could be few errors graver for Europe than to adopt the French model of the culture state.” And Malraux, the pivotal historical figure in the book, is cast by Fumaroli in a series of explicit and indirect comments as a fascist. Fumaroli’s screed contains pertinent cautionary remarks on the wisdom of separating culture from state control. I find, however, that Fumaroli gives Malraux short shrift, and associates him mockingly with “Nietzschean socialism.”

Herman Lebovics, a historian of modern France who teaches at SUNY, Stony Brook, brought out in 1999 a compact book with the jocose title Mona Lisa’s Escort: André Malraux and the Reinvention of French Culture. It maintains a healthy distance from the conventions of “cultural studies” and assembles a reliable brief biography of Malraux. Lebovics’s thesis, stated as a question in Chapter Four, surveys essentially the same events and issues discussed by Fumaroli:

With the coming of peace France had to find a government. Defeat and shame had discredited both the Third Republic in 1940 and l’État Français of Marshal Pétain in 1944. It was a moment of creation, and creation at this juncture in French history was closely linked to fiction. A new France had to be imagined. Two epic narratives met and melded in the task. How did the man who was the disembodied radio-voice of a fictional free France (what territories did it represent?) unite with the Promethean-Nietzschean artist-soldier that Malraux had made of himself?

In answering his own question, Lebovics gives almost equal time to De Gaulle and to Malraux and to their surprising devotion to each other. Here and in a few other places (e.g., “Fiction has taken over the everyday”), Lebovics comes close to interpreting reality as a matter of construction, and his glancing references to literary theory strike me as unconvincing and superfluous. But most pages in Lebovics’s book give evidence of a sound historian and a responsible biographer.

More dispassionately than Fumaroli, Lebovics shifts the discussion of Malraux’s years as minister of culture toward examining and questioning the relation of culture and state. The next-to-last chapter of Mona Lisa’s Escort affirms, “With the support of De Gaulle, Malraux nationalized the culture.” Three pages later it concludes, confusingly, “And Malraux made this French culture work better.”

In taking stock of Malraux’s record as government minister and agency head, we have been carried within sight of two dynamic situations, both of them political in the most positive sense of the word. The closest the United States has come to establishing a federal agency for culture has been its sponsorship of the National Endowment for the Arts. During its contentious forty-year history under several successive chairmen, the NEA has gradually attained an annual budget of $115 million. The current chairman, Dana Gioia, an ex-businessman and fine poet, has quite evidently pondered the political and cultural questions raised in earlier parts of this review. In the NEA’s 2003 annual report Gioia could be talking for Malraux in his ministerial capacity. Gioia speaks firmly of restoring the NEA “to its rightful place as the national’s leading institution for the promotion of art and arts education…by focusing on its stated core mission to foster excellence in the arts.” The following year in an NEA brochure entitled “How the United States Funds the Arts,” Gioia speaks with a bit more circumspection:

The NEA does not dictate arts policy to the United States; instead, it enters into an ongoing series of conversations about our culture…. It operates effectively …[as] a decentralized and constantly evolving system of private and public support for the arts.

We have some telling epithets with which to tar such a government undertaking, “bureaucratization,” for example. Yet the NEA is a modest organization that hardly threatens a healthy relation between culture and state. (Gioia tells us that the total NEA budget comes to about one tenth of the Italian government’s contribution to major opera houses.)

But we cannot stop here at a moment of comparable stasis. Must we raise now the prospect of a second wall of separation, this one between culture and state? I believe so. The culture/ state question borders further along on ominous territory that combines statecraft and aesthetics. A very condensed passage from an earlier essay of mine tries to survey this neglected territory:

We would do well to remember the passage in which Plato compares the philosopher-king to a painter working on the blank tablet of human character (Republic VI). Burckhardt, following Hegel, speaks of “the state” as a work of art. Trotsky refers to “directing events” and shaping society as “the highest poetry of the revolution” (Literature and Revolution). Some art aspires to the condition of high-handed autocracy known in our time as totalitarianism.5

Today, after having wrestled with the preceding pages, I’m inclined to change “totalitarianism” to “fascism.” For beginning with his early infatuation with Nietzsche and continuing through his Soviet fellow-traveling in the Thirties, Malraux faced a number of temptations to move toward fascism. He did not disavow his admiration for Barrès, Maurras, and Drieu la Rochelle, all of whom had affinities with it. Ironically, his close association with De Gaulle probably tempered the Nietzschean strain.

Malraux explored a vast intellectual and political terrain. But he was no fascist. He was a sacred monster who frightened and enchanted people with his inexhaustible command of words and the dimensions of his imagination. He sought the excitement of adventure and combat, but not the perverse pleasure of gratuitous cruelty toward others. His friends concur that he was a very kind man.6

This Issue

May 26, 2005

-

1

One of Malraux’s proposals was to have the treasured painting transferred in mid-Atlantic from a French to an American battleship.

↩ -

2

I have devoted a long essay to this remarkable congress, which provides a commanding view of the international political turmoil during the Red decade. See “Having Congress: The Shame of the Thirties,” in The Innocent Eye: On Modern Literature and the Arts (ArtWorks/Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2003).

↩ -

3

I also recommend two older books on the period—for France, David Caute’s Communism and the French Intellectuals 1914–1960, and for the US, Daniel Aaron’s Writers on the Left.

↩ -

4

Quoted by Gaëton Picon in Malraux par lui-même (Paris: Seuil, 1961).

↩ -

5

“The Demon of Originality,” The Innocent Eye, p. 63.

↩ -

6

I wish to express my gratitude to Walter G. Langlois for the help and criticism he has given me for this review.

↩