1.

In March 1848, the two Fox sisters, of Hydesville, New York, demonstrated that disembodied knocks and raps, presumably emanating from the beyond, occurred in rooms in which they happened to be present. Their mother soon displayed the same talent, and the three became a sensation, passing from local interest to international fame in what was, for the time, extreme speed. Although a neighbor reported that one of the Foxes had told her they were merely cracking their double-jointed knuckles, this had little effect on their reputation. Around the same time a young Scot, Daniel Dunglas Home, who claimed that his rappings predated the Foxes’ by two years, and who possessed a much wider repertoire of effects, including abilities to levitate and float, alter his height, handle fire, and physically manifest spirits, in addition to a degree of personal charisma not apparently enjoyed by the Foxes, became the first true star of the nascent belief system known as spiritualism.

That spirits of the dead could cross into the material realm and show themselves and even communicate with the living was an idea that took the Western world by storm in the late nineteenth century. Unsurprisingly, its popular appeal was cemented in the wake of the Civil and Franco-Prussian Wars, when large numbers of the bereaved sought to make contact with the untimely departed. But spiritualism also achieved, for a time, considerable intellectual respectability, enlisting prominent adherents in all countries. Victor Hugo and his family spent years regularly consulting what would later be called the Ouija board, at first trying to reach their dead daughter Léopoldine and eventually conducting dialogues with, among others, Dante, Shakespeare, the Ocean, and Death itself. The astronomer Camille Flammarion, a major scientist of unquestioned integrity, became the de facto leader of the movement in France. William James and Henri Bergson were both sympathetically inclined, if not actually enlisted in the ranks. For more than half a century the matter was taken seriously, if not necessarily endorsed, by almost everybody who had any sort of belief in posthumous existence.

That the phenomenon began suddenly did not trouble anyone, presumably since similar things had been reported by mystics and seers through the ages. That the physical manifestations were subject to continual upgrades does not seem to have aroused much skepticism at first, either. The spirits who modestly rapped on tables soon began to rotate those tables, tilt them from side to side, lift them into the air. Then spirits began to speak through a human intermediary, called a “medium,” and rattle chains, ring bells, blow trumpets, perhaps manifest their faces or even their robe-shrouded discarnate bodies. The mediums additionally might while in a trance state produce dribbles or streams of a substance called “ectoplasm,” a spectral goo somewhere between mucus and mozzarella on the viscosity index, allegedly manufactured by immaterial forces from the mediums’ own material fatty deposits. Sometimes the ethereal fluid even assembled itself into little rudimentary body parts.

That the manifestation of spirits would eventually be recorded by photographic means was inevitable, especially since spiritualism and photography had experienced coincidentally synchronous careers through the nineteenth century. The result, when it came, was mixed at best; although photography gave spiritualism enormous additional publicity, it fatally undermined the movement’s credibility. The pictures are, for the most part, grossly and transparently fake. Even allowing for ignorance of photographic processes by the wider public of a century ago, it seems incredible that anyone could have invested belief in “spirits” that are crudely lithographed and glaringly two-dimensional, or are identical in lighting, pose, and expression to photographs taken of the subjects in life, which suggests that either the dead are frozen forever in their most familiar earthly attitudes, or else the beyond is severely limited in its range of imagery.

The pictures obviously say a great deal about the nature of belief, about how the wish for heaven can make even intelligent and well-educated persons willfully suspend reasoning and disregard the evidence of their senses—a sadly relevant matter today. But some of the pictures also have a wild, irreducible beauty. They are meant to be photographs of the invisible, the inexpressible, the incomprehensible, and sometimes they succeed, at least in being deeply strange—for example, the picture by the researcher Albert von Schrenck-Notzing of the medium “Eva C.” (Marthe Béraud) generating a string of fire between her hands has a disturbing power that is not diminished by the knowledge that its salient effect was undoubtedly concocted in the darkroom.

The failures are just as good when the requirements of verisimilitude force them to disregard all the standards of photography as they were then understood; they are off-center, oddly or bluntly or badly lit, filled at their margins with the detritus of life—they look very much like keyhole views of the forbidden. Their roughness is their strength, as The Perfect Medium proves by including contemporaneous pictures of ghosts made to entertain skeptics and with no intent to deceive, which are invariably more polished, more stagy, more symmetrical, and much more predictable and jocularly dull.

Advertisement

The best spirit photos are those that look as though they couldn’t help being made, that are driven by an urgency that overpowers conscious control of the equipment, that not only represent phantoms but seem somehow to have been taken by them. Most of the pictures that fall into this category are the ones showing mediums at work. Often shot in conditions of near-total darkness, in domestic settings that usually look vaguely unclean, during performances that swing erratically between boredom and hysteria, these must rank among the most unstable and anxiety-inducing photographs on record. Either they document chaos, as people levitate and furniture goes flying, or else they show things that look utterly obscene without actually being pornographic, as when mediums are contorted by their possessing spirits or vomit up gushes of ectoplasm.

The spirit photographs per se mostly hew to the conventions of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century portraiture, although the presence of the revenants messes them up in interesting ways, the flurries of vignetted faces in the later period looking more frantically vital than the shrouded pale spooks of the earlier phase. There is a third category of photographs, those which purport to record “fluids” or auras or emanations or thought itself. These are most often abstract, are quite beautiful in a painterly way, and look like avant-garde works that could be produced even now. In fact they were avant-garde productions, employing cameraless photography—made by direct exposure of photosensitive plate or paper to light and shadow—and various kinds of darkroom manipulation decades before the Futurists and Surrealists began experimenting with them.

In their introduction to the catalog, the curators Pierre Apraxine and Sophie Schmit point out the limitations of a purely aesthetic approach to the photographs, which, they argue, is just as benighted as to judge them strictly on their claims. While it seems hard to imagine looking at these pictures without at least being curious about the conditions under which they were made—with the possible exception of the “fluid” photos, which can seem as though they were not made by humans at all—Apraxine and Schmit’s case is buttressed by the catalog of a German exhibition almost a decade ago that had two authors and a number of pictures in common with this one.*

In that show the spirit photos were matched with a selection of art-world productions from all across the twentieth century that seemed to bear them some relation, however vague. The mandate was exceedingly loose, including double exposures by El Lissitzky and rayograms by Man Ray among a panoply of works that share nothing but aspects of technique with the spirit photos—only the pieces that suggest the artist had actually been inspired by occult photography, such as the funny-creepy staged photos by the Belgian Surrealist Paul Nougé (dress shirts and a bell escape from a trunk, a woman is frightened by an animated coil of string, etc.), contribute anything at all to the intended dialogue. The art pictures seem to have been meant by the authors as a justification of the spirit photos, but employing that sort of aesthetic seal of approval can only result in condescension and diminution.

Photographs—all photographs, regardless of their intended use—are subject to aesthetic consumption and judgment. This was not always the case for pictures not intended as art. The idea was pioneered by the Surrealists in the 1920s, was very slowly approved by curators and institutions beginning in the 1950s, and has been generally accepted at least within the last twenty-five years or so. This represents an ironic reversal of the way things stood for more than a century, when photography waited outside the museum door, hat in hand, to be admitted under very particular conditions. Now every snapshot, mug shot, postmortem record, insurance document, and forensic exhibit is potentially an art object, and some of them possess more aesthetic vigor than many photographs taken with specifically aesthetic intent.

Such is the expanded range of our visual hunger and license that vernacular pictures often look strongest when they fly in the face of aesthetic conventions, even through ignorance or indifference—which in practice usually means that they anticipate, perhaps naively, the approaches of art photographers of future decades: flat, deadpan pictures of buildings and signs that precede Walker Evans, say, or compositions without an obvious center that seem to predict Robert Frank’s work. Painters taught art photographers the value of unlearning the prevailing conventions usually taken for granted, first of all, and then the photographers taught the rest of us. It has almost become a habit by now. There is also a certain agreeable shock value in removing pictures from their contexts altogether, although that only succeeds when the pictures are a priori iconic—when the provenance of the image and its train of associated meanings are instantly identifiable by the average viewer, such as in Richard Prince’s appropriated Marlboro cowboys, which means that they carry enough of their original context with them to put up a good fight in their new surroundings, generating tension by the very fact of being matted and framed.

Advertisement

On the other hand, photos that are less common and require some amount of explanation and historical placement tend to be neutered by being presented in a vacuum. The spirit photographs can be viewed as art objects—and the law of inversion holds, since the most powerful works in the genre are the least observant of the conventions of their time: the least composed, most chaotic, least polished, most apparently spontaneous, most frontally lighted—but they cannot be divorced from their history. By the same token, while they must be granted their historical context, that is not enough to make them intrinsically interesting. A show of discredited relics would be of interest only to antiquarians.

2.

The first spirit photographer whose works have survived was a Bostonian named William Mumler, who was developing a self-portrait in the spring of 1861 when he saw the faint image of a young girl beside his own in the wet-plate negative. He immediately assumed it was the result of his using a previously exposed plate that had not been cleaned sufficiently. He printed it anyway, and at length it came to the attention of the spiritualist press, which took it as proof positive that spirits could be photographed. Mumler, who later claimed to have been “mortified” by this, nevertheless quit his job as a jeweler’s engraver and set himself up as a professional medium-photographer. Within a year or two he was being investigated, by both skeptics and believers.

In 1863 a spiritualist recognized the shade appearing in his own portrait as someone still living, and denounced Mumler in the press. Similar incidents followed, and Mumler’s reputation languished until, in 1868, he moved to New York City and resumed his practice there, with great success. A year later he was arrested and charged with fraud and larceny. The resulting trial pitted photographers and skeptics, such as P.T. Barnum, against Mumler’s sitters, most of them spiritualists prominent in earthly affairs. The trial effectively put spiritualism in the dock alongside Mumler, and perhaps for this reason he was acquitted, although his reputation never quite recovered. He was forced to return to Boston, where he continued quietly taking spirit photos for another decade. Interestingly, all the pictures by Mumler in the show and the catalog date from that last decade, including one of Mary Todd Lincoln—who allegedly visited Mumler’s studio incognito—showing her late husband’s spectral form, his hands on her shoulders.

In France, the practice of spirit photography was delayed for a decade by the prudence of Allan Kardec, the original leader of the movement there, who warned his followers that ghostly images were all too easy to obtain by using badly cleaned plates. Kardec died in 1869; four years later, abetted by the Revue spirite, Kardec’s erstwhile organ, Édouard Buguet began producing spirit photos. There followed the usual investigative process, in which ostensibly agnostic scientists gave Buguet their imprimatur. The Revue spirite, for that matter, was not above enhancing previously published texts by Kardec to make them sound more enthusiastic about spirit photography. Nevertheless, Buguet’s moment lasted only about a year and a half. A Paris policeman investigating the spiritualist movement, ironically because of its possible ties to socialism, also happened to know something about photography. Buguet went on trial for fraud. Once in court, he promptly told all. Not surprisingly, his procedure involved sleight of hand, double exposure, and the sort of information-harvesting perfected by vaudeville mind-readers. He got a year in jail and a five-hundred-franc fine, and spirit photography in France became, as it were, a dead letter.

Great Britain never experienced that sort of preemptive court case, although controversies arose regularly. The strength of belief was such among British spiritualists that spirit photographers could be conclusively exposed as frauds and yet continue on for years afterward as if nothing had happened. William Hope made more than 2,500 spirit photographs between 1905 and his death in 1933, despite strong suggestions that he had switched plates and, later, irrefutable proof that he had employed a “ghost stamp”—“a small slide set into a tube, which, when light was passed through it, could leave a picture on a negative.” Ada Emma Deane produced nearly two thousand pictures before becoming a professional dog breeder in 1933. She was notorious for the pictures she made at several war memorial ceremonies in the early 1920s, in which a nebulous swirl of faces, apparently of dead soldiers, hovered above the crowd. Newspapers gleefully pointed out that the spirit faces included those of living athletes, but the exposure had no effect on Deane or her clientele.

Hope’s and Deane’s most prominent champion—in fact the world’s leading proponent of spirit photography in the twentieth century—was Arthur Conan Doyle, who after the success of Sherlock Holmes championed dozens of causes of all merits and descriptions. Perhaps because his second wife was a medium, perhaps because of his attempts to make contact with the spirit of a son who had died from war wounds, he was especially ardent on the subject of spiritualism, again and again staking his reputation on claims considered dubious at best by almost everyone. The most famous such incident began in 1920, when he declared genuine a number of photographs of fairies taken by two teenage girls in Yorkshire. Between the weight of Conan Doyle’s name and the fervor of the British spiritualists, the matter remained alive for years, and has continued to be cited in histories of the paranormal. It was not until 1981 that one of the perpetrators confessed that the fairies were drawings, held in place with hat pins.

To our eyes the tip-off is not just that the fairies are obviously flat, but that they are frozen in stylized postures that betray their origins in Edwardian popular illustration (their source, Princess Mary’s Gift Book, 1915, also contains a story by Conan Doyle). To people who wanted to believe, on the other hand, that peculiarity might have made them seem more rather than less credible, since it matched their expectation of what fairies would look like, which in turn had been conditioned by that style of illustration. Similarly, the sheet-draped ghosts in other photographs may look silly to us, but their intended audience found it natural that revenants would still be wearing the shrouds in which they were buried, or else that they would have been issued flowing classical raiments at the door of paradise. That the abstract photos of “fluids” appear the most otherworldly to us is in part the result of our own conditioning by a century of image saturation countered by the purity of abstraction. Another consequence is that today the leading motif in spirit photography carried out by believers is the “orb,” a glowing circle of light with no other visible properties that hovers in photos, frequently nocturnal but otherwise random, taken by digital cameras. The Internet is rife with sites devoted to these apparitions, which are not covered in the exhibit. The cryptophotography of the present day looks impoverished compared to the riches of the past, but it may well be that the passage of time will lend it charm.

3.

The most recent pictures in the show are forty years old now; they are also among the most mysterious. In the mid-1960s, Ted Serios, an elevator operator in a Chicago hotel, demonstrated the ability to produce images on Polaroid film held in a camera placed at a distance and triggered by someone else. He seldom succeeded in obtaining the specific images requested of him, but the images he did produce seem unaccountable, and his errors, if that is what they were, are often fascinating—asked for a picture of the Chicago Hilton, where he had worked, he came up with an image of the Denver Hilton instead. His heyday lasted three years, during which he was tested many times, the experiments witnessed by numerous scientists and stage magicians; the famous debunker James Randi was unable to reproduce the feat. But the Polaroids look very much like photographs of photographs, made on the fly. They are usually blurred and badly framed, but in their angles and lighting they give away their provenance in commercial photography. This may be more apparent to the present-day eye than to the eye of forty years ago, for which the crisp shadows and dynamic compositions of the travel-brochure imagery of the time merely mirrored contemporary reality. Perhaps investigators were misled into scrutinizing Serios—by all accounts a truculent drunk—when the actual trickery was engineered by one or more of his ostensible supervisors, but the brief catalog essay does not specify whether that line of inquiry was ever pursued.

The willfully nonjudgmental tenor of the essays in the catalog can be frustrating, but their delicacy of tone is finally rather admirable. Since most of the pictures are so bare-faced that few present-day viewers will manage to suspend disbelief, an exhibition apparatus given over to debunking would appear heavy-handed, if not tautological. The texts, generally, only permit themselves a discreetly cocked eyebrow. In describing the efforts of one Alexander Aksakov to refute the charge that spirit manifestations were merely collective hallucinations by producing a picture showing both spirit and medium, Andreas Fischer merely notes that “the monitoring arrangements had been so inadequate that doubt remained.”

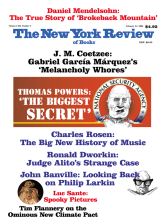

The restraint of that phrase is exquisite in its context: a blurred, off-kilter photo of a beefy character in robe, turban, and fake beard clutching the puny medium in a linebacker’s embrace. The catalog is certainly a better way to appreciate the pictures than the museum show, not only because its essays give a more comprehensive account of the history than wall texts could manage, but also because a majority of the photographs are tiny—many of them cartes de visite, such as the cover image, which is there blown up to ten times its size—and are easily lost in the vast rooms and surging crowds of the Metropolitan Museum.

The work engaged here is rich, so rich that it overflows the catalog, leaving all sorts of half-told tales and unexplained oddities. But what is missing lies outside the scope of a museum catalog. The pictures may ostensibly document the realm of the immaterial, the post-human, the ether, but they are moving precisely because of the grubby human and material stories they inadvertently disclose, of boundless grief and stubborn self-deception and feeble guile and pathetic compromise. They speak of propriety and barbarism, doubt and obsession, love and chicanery, exaltation and despair. They embody every sort of contradiction and every affective extreme. They can be terrifying, not because of their sideshow ghosts or tinpot effects, but because of the emotional undertow that lies just beneath their surfaces. It is not hard to imagine being unbalanced by loss and then thrown into a darkened room where the last tenuous grasp of reality finally gives way, or to imagine larkishly producing a hoax and then finding that a great number of people have become psychologically dependent on its indefinite perpetuation. There is a great unwritten book, or more than one, lurking behind these pictures, but it could only be a work of the imagination.

This Issue

February 23, 2006