During the summer of 1948, when he was twenty-one, the poet W.S. Merwin made his first trip to Europe. Merwin had graduated from Princeton and was newly married, but the voyage was hardly a honeymoon. His unraveling first marriage was part of the old life Merwin was leaving behind: his cramped childhood in a Presbyterian minister’s household in Pennsylvania; his stint in a boarding school for the children of Protestant ministers; his proposal on a whim to the secretary of the physics department at Princeton. An invitation to serve as tutor to the nephew of a rich and shadowy American provided the means of escape, “the arrival of the beginning of freedom.” Merwin’s book opens with a beautiful and enigmatic sentence: “A summer descends on us from earlier years, heir to ancestors it never knew.” The summer of 1948 is the major “doorway” of Merwin’s title, the threshold he had to cross to discover—as all the classic writers of autobiography discover—the new life waiting for him on the other side.

There are fairy-tale elements to Merwin’s narrative of the summer that changed his life. He enters an enchanted world of princesses and movie stars, villas perched like migratory birds on the cliffs of the French Riviera, and forests in the heart of New Jersey where deer and elk walk amid trees hundreds of years old. One advantage of writing nonfiction is that it doesn’t have to be plausible; it just has to be true. A fine writer of prose as well as a major poet—his volume of new and selected poems, Migration, gathers work from a score of books and won a National Book Award for 2005—Merwin has written a wise and moving book about how he became a writer.

The opening chapters of Summer Doorways, which evoke the life that Merwin left behind, have a dark, nineteenth-century tone, punctuated with small illuminations. Merwin’s father, a “distant, unpredictable, and harsh” man who frowned on dating and dancing, seems a figure out of Stephen Crane, another minister’s son who escaped to Europe: “He had punished me fiercely for things I had not known were forbidden, when the list of known restrictions was already long and oppressive.” It is a measure of the claustrophobia of the household that Merwin’s job cleaning the science labs at his boarding school, in “the big, square, dark red brick building that I associated…with the end of the Civil War and the presidency of Ulysses Grant,” seems like a release.

There is a magical moment when, already accepted at Princeton in the spring of his senior year of high school, Merwin and another boy are washing upper-story windows:

We had straps with swivel hooks to hold us in place as we stood on the cement window sills, up among the rustling leaves, watching the street and the campus from the birds’ height. The sense of risk, the recurrent rush of vertigo, nourished an elation, a foretaste of freedom, a floating happiness that accompanied me, and my bucket, reflected in the panes of window after window, and stayed with me as we carried the buckets and squeegees and rags down the marble stairs and as I went across the street to the dormitories and upstairs to my room.

That second sentence, with its suspended phrase “and my bucket,” has a pleasing disequilibrium befitting its subject. This bucket-carrier—risk-taking, observant, reflective, and free—is an image of the poet and his oblique perspective on the world.

Princeton, its population of privileged rich kids depleted by the war, offered more intimations of a wider life for Merwin, who was by his own account “provincial, naïve, and penniless.” Wandering one day across the campus, he stumbled upon the empty riding hall, “with its light like the inside of a paper bag,” and its stable of a dozen horses, “all under the eye of a depressed retired jockey sitting in the tack room by himself, out of his mind with boredom.” His previous equestrian experience limited to some penny pony rides, Merwin offered his services as an exercise rider, and soon was taking exhilarating midnight rides bareback, out into the woods and the open country. The episode tells us something important about Merwin. Somehow, in those early years squeezed into pews, he developed an appetite for experience, and an aptitude for embracing and shaping whatever meager possibilities fell in his path.

Merwin has written elsewhere of the literary side of his days at Princeton, where he was part of the “shabbier, nerdier, motley skeleton crew on working scholarships.” He was lucky in his company there, making friends with the pianist and scholar Charles Rosen, the poet Galway Kinnell, and the classical scholar and translator William Arrowsmith. At Princeton Merwin also discovered his “intellectual fathers,” the critic Richard Blackmur and the poet John Berryman, who at the time was Blackmur’s assistant. In a striking poem titled “Berryman,” from his collection Opening the Hand, Merwin has described Berryman’s single-minded devotion to poetry:

Advertisement

I asked how can you ever be sure

that what you write is really

any good at all and he said you can’t

you can’t you can never be sure

you die without knowing

whether anything you wrote was any good

if you have to be sure don’t write

The portrait of Berryman in Summer Doorways is less affectionate. Berryman, “high-strung, with high-flown odds and ends of an English accent,” would take Merwin’s latest attempts at verse and “unhesitatingly, mercilessly, reduce them to nothing.” Berryman seems a reminder of Merwin’s fault-finding father here; his acquired accent and his restrictive taste for British poets seem emblematic of yet another suffocating tradition to escape from. Merwin, who was reading deeply in Romance languages and the novels of Gide and Mann, came to value Blackmur’s magnanimous wisdom more highly than Berryman’s caustic aestheticism.* Blackmur believed that art and literature were “inexhaustible,” but nonetheless were “not greater than the whole of life that they represented.” Merwin quotes Blackmur’s remark that a literary critic was a “house waiting to be haunted.” Though Merwin doesn’t say so, Blackmur borrowed this phrase from Emily Dickinson, on whose work he had written a pioneering essay. “Nature is a Haunted House,” Dickinson wrote her own mentor, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, “but Art—a House that tries to be haunted.”

Houses haunted in various ways are central to Summer Doorways, especially to its second half, where the sense of enchantment is strongest. One such haunted house is the ancestral mansion of the Stuyvesant family, in the wooded interior of New Jersey. Alan Stuyvesant, a direct descendant of Peter Stuyvesant, the Dutch governor of New Amsterdam, and son of the Belgian Princesse de Caraman-Chimay, hired Merwin, who was finishing his undergraduate work at Princeton in the spring of 1947, as tutor to his nephew Peter. Alain Prévost, a classmate of Merwin’s at Princeton, had introduced him to Stuyvesant. Merwin learned that Stuyvesant, despite an earlier affection for Franco’s fascism during the 1930s, had been parachuted into a mountainous region in the south of France during the summer of 1944, as part of American efforts to join forces with the Resistance. Stuyvesant’s mission was to make contact with a Resistance fighter he had known before the war, the writer Jean Prévost, Alain’s father. Prévost was later killed by German soldiers and Stuyvesant assumed partial responsibility for his children.

Stuyvesant’s New Jersey estate (long since bulldozed to make way for highways and shopping malls) was known as the Deer Park, five thousand acres of ancient woodland, much of it untouched since the seventeenth century: “It could have been part of the landscape that the first Europeans saw there, and that the tribes had known as the world, before that.” Merwin relishes the “rooted plainness” of the house, some of it dating from pre-Revolutionary times, with its stone stairs and windows “set low in the walls, framed as though they were in boxes.” Under the guidance of Alan, an architect by profession, Merwin glimpses a vision of the ordered life that left its mark in the spacious house and “the unremembered lives it had harbored.”

At the same time, Merwin is troubled by the violence that made such houses possible:

Most of the house, as it was then, must have been built in the years following the Civil War, the heyday of the robber barons…. That had been the age of the self-righteous terminations known as the plains wars. Through the seizure of the West with its massacres and justifying, the floors and turrets and Tiffany windows had gone up here.

Merwin’s ambivalence reminded me of Yeats’s lines from “Ancestral Houses,” the first section of “Meditations in Time of Civil War”:

Some violent bitter man, some powerful man

Called architect and artist in, that they,

Bitter and violent men, might rear in stone

The sweetness that all longed for night and day,

The gentleness none there had ever known.

No such ambivalence attaches to the European houses to which Stuyvesant gave Merwin access the following summer, after the transatlantic voyage on a Norwegian freighter. The account of his stay in the Stuyvesant villa in St. Jean Cap-Ferrat on the Riviera recalls Jean Renoir’s Rules of the Game: the courtly but distant host; the mismatched pair of movie stars visiting from Paris; the failed French architect with his suicidal wife; assorted servants with their “weathered attachments” and “commemorative affections”; and Merwin himself, the aspiring poet, observer, and tutor to the host’s nephew. As in Renoir’s film, secrets and “unappeased urges”—especially Alan Stuyvesant’s—gradually come to light. There is no culminating gunshot, just a tawdry scene at Maxim’s in Cannes, when Stuyvesant reacts unexpectedly to a transvestite performer:

Advertisement

Alan suddenly heaved himself onto his feet and, shouting obscenities at the dancer, flung himself onto the dance floor trying to lay hands on him. Instead he fell onto his face and lay there while the waiters leapt forward to help him to his feet, and to restrain him.

What began so promisingly—the glistening summer on the jewel-like harbor—ends in squalor, as a dance band keeps playing “La Vie en Rose” in a dive down by the Vanderbilt villa.

Merwin gives a vivid account of the Gatsby-like comings and goings: “Mrs. McCormick (of McCormick harvesters) came with her own beautiful daughter, Muriel. It was no secret that Mrs. McCormick had her eye on a titled English bachelor for Muriel.” Somerset Maugham, “tortoiselike,” floats into view, and, after “a few syllables croaked or whispered,” recedes. Merle Oberon and Eric von Stroheim are glimpsed at separate tables at the casino in Monte Carlo. Merwin admires the dedication of a young translator called Georges Belmont who lives nearby, a friend of Henry Miller and Samuel Beckett; but he also detects a warning in Belmont’s long hours of translating “to buy himself a little time to work on poems and a novel of his own.” Merwin senses in Belmont “an ultimate doubt of himself,” a suspicion “that he was a shadow of others.”

Belmont introduces Merwin to an Irish novelist, John Lodwick, who shares Merwin’s fascination with Camus and Thomas Mann. They discuss the pact at the heart of Mann’s Doctor Faustus:

At one point he wanted me to say whether, if—like the composer who was the protagonist of Mann’s great novel—I had been offered a period of years of artistic fulfillment in exchange for something I thought of as my soul, I would have accepted. I was startled by the question, and answered that I thought I would have had difficulty believing in the “devil’s” offer at all, and the authority for making it. I thought that if the talent and urge and character were there to begin with, such a bargain would be meaningless. If they were not there, no “bargain” could help.

In Summer Doorways Merwin describes how he came to recognize and protect his own “talent and urge and character,” and to preserve his determination not to become a shadow of other people.

The emotional anchor of Summer Doorways lies in the closing section, when another friend of Stuyvesant’s, Maria Antonia da Braganza of the royal family of Portugal, and sister to the pretender to the throne, offers Merwin a chance to remain in Europe as English tutor to her boys. Her ancient farmhouse across the Pyrenees feels “like a homecoming” for Merwin, a more benevolent version of the Deer Park. Here, in the old farm, or quinta, among stone steps and ruined walls, he senses “the profound continuity of the peasant world…a current of existence that was older than any of the chronicles, or any of the great names of the ruling families.”

There is a bit of primitivism in Merwin’s admiration here, a delight in peasant routines that the hardworking peasants themselves might not share. Merwin’s concerns about gentility gained through violence, so evident in his response to the Deer Park, vanish in this traditional European world. Perhaps, as an American visitor, he feels no guilt at age-old arrangements. Again, we sense the poet’s perspective, the bucket-carrier slightly outside the scene, finding the sources of his imaginative strength. Summer Doorways ends on an almost ecstatic note:

But when we left the quinta I had seen something that I was to come to in various forms before I was old enough to be able to look back and recognize it. The move away from the valley of the Ceira would lead through years in which, again and again, I would have the luck to discover, to glimpse, to touch for a moment, some ancient, measureless way of living, of being in the world, some fabric long taken for granted, never finished yet complete, at once fixed as though it would never change, and evanescent as a work of art, an entire age just before it was gone, like a summer.

Merwin’s work in verse and prose has seemed to trace, for some time now, a “route of evanescence,” to borrow another phrase from Emily Dickinson. In the rueful “Cover Note” to his volume Travels, Merwin worried not only about the disappearance of the subjects from the natural world that poets care about—

…the one

owl hunting along this

spared valley…

—but of any audience for poetry itself:

…I do

not know that anyone

else is waiting for these

words that I hoped might seem

as though they had occurred

to you…

In his new book of poems, Present Company, these concerns have intensified. In a series of poems surrounding September 11, 2001, each carrying its date of composition, Merwin finds himself again, as in Summer Doorways, at the end of summer. In “To the Light of September,” dated September 10, he addresses the shifting light:

and for now it seems as though

you are still summer

still the high familiar

endless summer

yet with a glint

of bronze in the chill mornings

and the late yellow petals

of the mullein fluttering

on the stalks that lean

over their broken

shadows across the cracked ground

Just a week later, Merwin, like so many of us in the aftermath of that fateful morning, feels that he has entered another season, almost another age. “To the Words,” written on September 17, is already a familiar and often-quoted poem. Here are its closing lines, addressed to the words that existed before the poet and will outlive him:

you that were

formed to begin with

you that were cried out

you that were spoken

to begin with

to say what could not be said

ancient precious

and helpless ones

say it

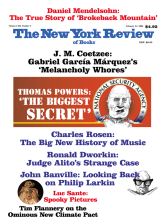

This Issue

February 23, 2006

-

*

Of Blackmur’s “spacious” intelligence, Merwin has written: “I had revered the low-keyed luminous acuity of his insight, which played constantly over everything literary and nonliterary. He was certainly the most perceptive and spacious literary intelligence I had ever been close to, someone of a profound, private, and—I believed—reliable, indeed oracular wisdom.” The passage comes from Merwin’s fine essay “The Wake of the Blackfish: A Memoir of George Kirstein,” in The Ends of the Earth (Shoemaker and Hoard, 2004), p. 16.

↩