Shortly after midnight on May 18, 1922, in a private dining room at the Hôtel Majestic in Paris, a glittering group of writers, artists, musicians, and patrons of the arts gathered to celebrate the first public performance of Stravinsky’s burlesque ballet Renard, choreographed by Bronislava Nijinska. The ballet had been performed that evening at the Paris Opéra, to a puzzled but polite audience, by the Ballets Russes of Serge Diaghilev, who also stage-managed the supper party. Nine years had passed since the riotous première of Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du printemps. To judge by the reviews of Renard quoted by Richard Davenport-Hines, audiences were now more likely to be intrigued than offended by Modernist experiments. According to the New York Herald’s critic, M. Stravinsky “is going through a process of evolution which, however, is not likely to be followed easily by the public.”

Even this muted acknowledgment of creative autonomy would have been unusual a decade before. Incomprehensibility was no longer universally deemed an artistic defect. Stravinsky and the other star guests at the Hôtel Majestic that evening in 1922—Pablo Picasso, James Joyce, and Marcel Proust—enjoyed the admiration of a small, passionate minority who read the latest volume of Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu on the Métro and reveled in the obscurity that seemed to be the mark of genius. They attended Picasso’s exhibitions and Albert Einstein’s lectures on relativity (held in Paris in March and April that year), expecting to be pleasantly baffled.

No doubt this was evidence of intellectual curiosity, but there was also an element of snobbery. Like the luxurious Hôtel Majestic, Proust’s sentences and Einstein’s equations had the charm of exclusivity. Two of Proust’s contemporaries, quoted by Davenport-Hines, significantly likened Proust’s syntactical complexities to what were then exclusive, upper-class pursuits. Violet Hunt found that Proust “backed his sentences in and out of garages like a first-class motorist.” E.M. Forster sniffily compared the experience of negotiating Proust’s expansive, flowery phrases to a shooting expedition: “Three fields off, like a wounded partridge, crouches the principal verb, making one wonder, as one picks it up, poor little thing, whether after all it was worth such a tramp, so many guns, and such expensive dogs.”

The exclusive supper party at the Majestic was the idea of an English couple, Violet and Sydney Schiff, who paid for the whole event. While Violet amused herself with matchmaking, Sydney, whose novels in the Modernist style are now quite forgotten, seems to have spent much of his time ingratiating himself with prominent members of the avant-garde. He was particularly infatuated with Marcel Proust. “He tried to insinuate his way into every corner of Proust’s most intimate existence,” says Davenport-Hines. He pestered him with invitations and sent him strangely tactless and flirtatious letters. On one occasion, he insisted on knowing where Proust’s maid bought his writing paper: “I would love to have the same as yours in the same way that I would provide myself with the same scent as that of a woman whom I loved. Only in your case it’s a great deal more serious.” His passion had not, however, induced him to read the novel that was written on that paper. Ignoring Proust’s theory that writers and their work are entirely separate, Schiff told him that it was pointless to read a friend’s work when the friend could be visited in person, just as it was futile, according to him, to listen to a gramophone record of a singer who was still alive.

Although the party at the Majestic was held in honor of Diaghilev, the Schiffs’ main purpose was to introduce Marcel Proust to James Joyce, whose Ulysses had been published that February. The Schiffs behaved like zookeepers coaxing two rare and skittish beasts into the same cage and hoping that something magical would come of their brief union—a bon mot, a fascinating discussion, a lasting friendship. The scene was set for one of the great meetings of Modernist minds. The food had already been cleared away when a shabby, drunken man blundered in, sat down next to Sydney Schiff, and, according to the art critic Clive Bell, “remained speechless with his head in his hands and a glass of champagne in front of him.” Later, he was heard to snore. This was the author of Ulysses. Then, between two and three o’clock in the morning, a small, dapper figure wrapped in a fur coat slipped into the dining room. If Clive Bell’s description is accurate, he looked somewhat like a rat: “sleek and dank and plastered.” This was the author of À la recherche du temps perdu.

Joyce and Proust failed to live up to the historic occasion. There was no sparkling conversation and the two writers never met again. This did not prevent gossips and writers of memoirs from inventing the dialogue later on. Davenport-Hines quotes six different versions, the most interestingly boring of which is the version Joyce himself gave to Frank Budgen:

Advertisement

Our talk consisted solely of the word “No.” Proust asked me if I knew the duc de so-and-so. I said, “No.” Our hostess asked Proust if he had read such and such a piece of Ulysses. Proust said, “No.” And so on. Of course the situation was impossible.

The ride back in the taxi was slightly more eventful. Joyce lit a cigarette and opened the window. Proust, who hated drafts, chattered continuously, without looking at Joyce. When they reached Proust’s home in the Rue Hamelin, Joyce tried to get himself invited in, but Proust insisted, “Let my taxi take you home.”

There is, therefore, a certain irony in Davenport-Hines’s title. It turns out that very little is known about the party at the Majestic. Unusually for such a notable occasion, the guest list and menu were not published in the newspapers. We know that Picasso wore a red Catalan sash around his head, but not what he said. The almost total lack of information would probably have pleased one of the guests, Ernest Ansermet, conductor of Renard, who once told a New York journalist, “Write in your article: this artist doesn’t have any anecdotes.” The party serves mainly to introduce the eccentric figure of Marcel Proust through other people’s eyes before the story plunges into the privacy of his mind.

This is a splendidly Proustian approach to biography: anecdote and gossip paint a portrait of the subject from several different angles before his real, far stranger idiosyncrasies are revealed. The structure of the book also mirrors the structure of À la recherche du temps perdu. Just as Proust’s narrator writes with a sense of death’s imminence, Davenport-Hines begins his chatty, passionate, and scrupulous account with the event that was “the social climax of the last year of Proust’s life.” Exactly six months after the party at the Majestic, on November 18, 1922, after making some final changes to the death scene of one of his characters, Marcel Proust died of septicemia.

The apartment to which Proust returned after the party at the Majestic was to be his last home. His earlier apartment at 102 Boulevard Haussmann, where he had lived for almost thirteen years, was already one of the legendary sites of literary Paris. Comparing it to his own hectic apartment, Joyce had enviously imagined it as a blessed haven: a “comfortable place at the Étoile, floored with cork, and with cork on the walls to keep it quiet.” The famous cork lining was the best-known feature of an artificial environment entirely devoted to the production of a novel. It begs the question: Why did the hypersensitive Proust expose himself at all to the noise of traffic and neighbors, the “acrid smell” of the maid’s laundry and the pollen of the chestnut trees along the boulevard that exacerbated his asthma? He was rich enough to afford a detached suburban villa. He had a chauffeur and a telephone. With its 280 miles of pneumatic tubes and its army of bicycle messengers, the Paris postal service was efficient enough for the needs of any writer.

In fact, as Davenport-Hines points out, Proust was not averse to neighbors. When he lived on the Boulevard Haussmann, he liked to listen to the sounds of lovemaking that came through the wall, just as he helped to finance a homosexual brothel so that he could secretly observe the antics of its customers. When his maid Céleste asked him how he could watch such things, he replied, “because it could not be made up.” He enjoyed loud and boisterous parties, and he even seemed to relish the constant interruptions of the ineffectively sycophantic Sydney Schiff. The cork lining was part of Proust’s cordon sanitaire (a concept first developed by his father, Dr. Adrien Proust), but it was also part of a filtration system that was designed to admit only those stimuli that Proust deemed necessary for his work.

If Joyce had been allowed to see that “comfortable place,” he would have found not a cosy writer’s lair but a clinical chamber. “The cold was so great,” according to one of Proust’s visitors, “that one felt like a fish being kept fresh.” There was no desire to please the eye. The objects were not ornaments but the apparatus of experiments in progress. Sydney Schiff noticed that a particular object—a jug, a coffee cup, or a half-emptied beer glass that had caught the sun in a particular way—would be left where it was. “Sometimes he insisted on it remaining indefinitely, because he wanted to renew the sensation it had given him.” In À la recherche du temps perdu, these apparently trivial sensations occur only by chance. They bring about the epiphanic moments when the narrator grasps the whole “edifice of memory” and can begin to transform “lost time” into a work of art. In Proust’s apartment, those sensations were continually on tap. The apartment in the Rue Hamelin was a novelist’s laboratory in which involuntary memories could be generated at will.

Advertisement

One of the merits of Davenport-Hines’s account is that it shows the extraordinary degree of deliberation that lay behind almost all of Proust’s activities. He may have suffered from exquisite sensitivity, as he often complained, but he took steps to ensure that that sensitivity never waned. A man who has his walls sound-proofed with cork is inevitably reminded of his sensitivity, and a man who subjects himself to a steady diet of caffeine, opiates, barbiturates, amyl nitrate, and pure adrenalin is unlikely to remain oblivious to the functioning of his brain. The quantity and variety of drugs that went into the writing of À la recherche du temps perdu are probably unparalleled in French literature. Proust urged his critics not to trace facile patterns of cause and effect when analyzing the process of literary creation, but it is probably reasonable to suppose that the vivid, hallucinatory memories that the narrator of his novel enjoys at intervals of several years were more common occurrences for the author, and that they were produced by substances less innocuous than a madeleine dipped in a cup of herbal tea.

Davenport-Hines, who has written a fascinating and well-researched history of narcotics,1 recognizes in Proust “the habitual drug user’s cunning”: even during World War I, by manipulating a reluctant admirer, Proust managed to keep himself supplied with Swiss and German drugs. But he also recognizes Proust’s habitual intoxication as a means of sustaining “his explorations in the exciting serendipitous jungles of the unconscious.” Like his character Bergotte, Proust experimented with drugs out of professional curiosity rather than simple self-gratification. Bergotte’s sampling of narcotics is described in La Prisonnière (one of the posthumously published volumes of À la recherche du temps perdu) as a sexual adventure combined with a voyage of discovery:

One absorbs the new product… with delicious anticipation of the unknown. The heart pounds as it does on one’s first meeting with a lover…. By what strange paths, up to what peaks and into what unexplored abysses will the omnipotent master lead us? What new series of sensations will we discover on this journey?

To his contemporaries, and especially to his parents, Proust’s social life might have seemed repetitive and wasteful, but when he sat at his table in the Ritz, eating asparagus with his gloved hands and listening to the gossip, who knows what daring exploits his mind was undertaking?

The same devout self-centeredness was evident in Proust’s relations with other people. Davenport-Hines’s study is full of thumbnail sketches of Proust’s acquaintances. They come and go like people at a party and seem to show that the denizen of the cork-lined room was also a profoundly sociable creature. It soon becomes apparent, however, that none of these people was a friend in the normal sense of the word. It is entirely appropriate that the social event that gives this book its title was, for the purposes of literary history, such a conversational and anecdotal nonevent. In 1922, Proust was no longer the ambitious young snob who frittered away his time in idle conversation with members of the nobility. He was a novelist in a race against death who pumped his friends for information, wined and dined them when they gave him good reviews, and persuaded them to award him the Prix Goncourt. When he had no more use for them, he dropped them. “Artists,” he wrote in the volume that won the Prix Goncourt (À l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs), are

under an obligation to live for themselves. And friendship is a dispensation from this duty, an abdication of self. Even conversation, which is the mode of expression of friendship, is a superficial digression which gives us no new acquisition.

Samuel Beckett memorably defined Proust’s conception of friendship in his monograph of 1931, which Davenport-Hines quotes:

Friendship [for Proust] implies an almost piteous acceptance of face values. Friendship is a social expedient, like upholstery or the distribution of garbage buckets. It has no spiritual significance. For the artist, who does not deal in surfaces, the rejection of friendship is not only reasonable, but a necessity.

This might explain Proust’s peculiar attachment to Sydney Schiff, his host at the Majestic. Schiff was not just a fluent source of trivia and gossip, he also embodied certain kinds of interesting stupidity and arrogance. Schiff’s slavish devotion, his accidentally insulting compliments, and his extraordinary vanity are strongly reminiscent of some of Proust’s least pleasant characters. As a connoisseur of vanity, Proust could hardly have been indifferent to the man who proposed himself as the ideal English translator of À la recherche du temps perdu—without having read it all—because “there’s no-one who understands you as we understand you,” though “you wouldn’t know it from listening to my execrable spoken French”: “it’s a question of my sympathetic intuition, of my literary taste and my intellectual faculties.”

None of this will surprise readers who are already familiar with Proust’s life and legend. The originality of Davenport-Hines’s study lies in the cheerful emphasis that he places on Proust’s homosexuality. Its crucial importance to his life and work has not been demonstrated so forcefully since J.E. Rivers’s study Proust and the Art of Love, in which he suggested that À la recherche du temps perdu may have begun “as a nonfiction essay on homosexuality, which gradually grew into a novel, as Proust saw broader and broader implications in his subject.”2

A year before the party at the Majestic, Proust had published the first part of the fourth volume of À la recherche du temps perdu under the bold title Sodome et Gomorrhe. The opening episode, in which the narrator witnesses Baron de Charlus picking up Jupien and then eavesdrops on their lovemaking, is one of the earliest scenes in modern literature in which an unambiguously homosexual act is depicted without a show of moral outrage. This was an act of great courage on the part of a writer who cared almost to the point of obsession about the opinion of his readers. In France, homosexual acts had been implicitly legalized by the Code Pénal of 1791, but “sodomites,” “pederasts,” “amateurs,” “tantes,” and “unisexuals” were frequently arrested for public indecency. Even a rumor of aberrant sexuality was enough to destroy a career.

Proust, who had always publicly denied that he was homosexual, was justifiably worried about reactions to Sodome et Gomorrhe: “When M. de Charlus appears, people everywhere will turn their backs on me, especially the English.” He was presumably thinking of the trials of Oscar Wilde and of the fact that homosexuals were persecuted more enthusiastically in England than anywhere else in Europe. In the event, he found that many reviewers, though privately horrified, remained tactfully silent. Ezra Pound, for instance, reviewing the “new lump of Proust” in The Dial, ignored the subject altogether, though he mentioned Proust’s “pimps, buggers and opulent idiots” in a letter to a friend.

The British reaction was openly hostile. The New Statesman’s reviewer of The Cities of the Plain (the euphemistic title of Charles Kenneth Scott Moncrieff’s translation, published by Alfred Knopf in 1929) found that, after Proust’s “analysis of degenerates,” “one escapes with relief to the sturdy, virile world of Fielding, or even to the coarse naturalism of Zola.” Traces of this aversion can still be found, even among Proust’s admirers. In his immense and factually reliable biography of Proust, Jean-Yves Tadié, general editor of the Pléiade edition of À la recherche du temps perdu, treats the subject discreetly and sometimes with obvious distaste. Dismissing evidence of some of Proust’s sexual practices, he writes, “We should console ourselves with the thought that no historian has ever classified writers according to their sexual achievements.”3 Tadié’s view of what he calls “inversion” (a nineteenth-century medical term for what was supposed to be a congenital condition) is entirely consistent with views that prevailed in Proust’s day.

Davenport-Hines, by contrast, discovers Proust’s homosexuality “at the core of his sensibility.” He does not treat Proust’s capacity for falling in love with people of his own sex as an awkward handicap, except, briefly, when considering Proust’s habit of transposing homosexual memories into heterosexual scenes. As he points out, many of the heterosexual love scenes in the novel are “feeble, even ludicrous” but “more convincing when men are somewhere in the background.”

By a sad irony, Proust’s reputation was protected partly by the fact that relatively few readers got beyond the first part of À la recherche du temps perdu. They knew the narrator as the delicate boy who lies awake, anxiously waiting for his mother’s goodnight kiss, but not as the ithyphallic man who tries to embrace women who accidentally brush against him in the street and who is cautioned by the Head of the Paris Sûreté for fondling little girls.

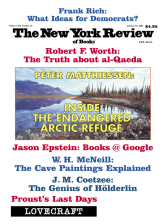

Proust himself emerges from this book as a marginal figure, a bourgeois among aristocrats, a homosexual in an openly homophobic age, the Dreyfusard son of a Jewish mother who, though he was baptized a Catholic, never repudiated his Jewish roots and associated the plight of homosexuals with the plight of Jews in an anti-Semitic society. The writer who first appears as a partygoer eventually seems too detached from Parisian life to justify the subtitle: The Last Days of the Author Whose Book Changed Paris. The title of the British edition makes no such claim—A Night at the Majestic: Proust and the Great Modernist Dinner Party of 1922—and Davenport-Hines does not try to show that Proust had any effect on Paris, other than by making homosexuality a slightly more acceptable topic for conversation. He shows him in his last months trying to keep abreast of what was going on in the world beyond his drawn curtains. He was a “consumer of journalism” and a “monitor” of events, not a social reformer. For all its structural, linguistic, and psychological modernism, his novel seemed increasingly to be the record of a bygone age, a farewell to Victoriana and, as the weak, passive title of the English translation had it, a “Remembrance of Things Past.”

If Proust had ever claimed to have “changed Paris,” he might have referred to the intangible effect of his novel on perceptions of the city, just as he noted, in À la recherche du temps perdu, the apparent influence of certain painters on reality:

I continued to visit the Champs-Élysées on days when the weather was fine, walking along streets whose elegant, pink houses bathed in a light and changing sky because watercolor exhibitions were then the height of fashion.

Women pass in the street, different from those of earlier days, because they are Renoirs—those Renoirs in which we formerly refused to see women.

This might not seem like much of an achievement compared to the historic significance of the great Modernist dinner party of 1922, but it was precisely such flimsy, fleeting visions that gave Proust’s novel its peculiar depth and its constant promise of revelation and redemption. Davenport-Hines aptly pays homage to Proust by adorning his description of the funeral procession with references to the novel: the district of the Champs-Élysées, which had seemed so melancholy to the young narrator; the obelisk on the Place de la Concorde, which a summer sunset turned into pink nougat. “Paris, throughout Proust’s final journey, had never seemed richer in Proustian associations.”

Proust’s funeral, with which Davenport-Hines ends his account, was a greater gathering of celebrities than the party at the Majestic, but even there, the conversations and the grandiloquent pronouncements were trivial compared to the involuntary impressions of those who witnessed the great event. As Proust had written in the last volume of his novel, major events—even the Dreyfus Affair and the Great War—gave writers reasons to procrastinate. They provided them with an excuse not to decipher “the internal book of mysterious signs,” “the only book that reality has dictated to us.” After the funeral, when she returned to the empty apartment in the Rue Hamelin, Proust’s maid Céleste had already begun to read her own version of that book. As she wrote in her memoir, Monsieur Proust, she saw her master’s works displayed in an illuminated bookshop window in groups of three. Years later, when she recreated the scene in her memory, it turned into the manifestation of a passage from La Prisonnière, which was published a year after the funeral:

They buried him, but all through the night of mourning, in lighted bookshop windows, his books arranged three by three kept watch like angels with outstretched wings and seemed, for him who was no more, the symbol of his resurrection.

This Issue

October 19, 2006

-

1

The Pursuit of Oblivion: A Global History of Narcotics (Norton, 2002).

↩ -

2

J.E. Rivers, Proust and the Art of Love: The Aesthetics of Sexuality in the Life, Times, and Art of Marcel Proust (Columbia University Press, 1980), p. 24.

↩ -

3

Jean-Yves Tadié, Marcel Proust, translated by Euan Cameron (Viking, 2000), p. 674.

↩