In response to:

Cultivating Voltaire's Garden from the December 15, 2005 issue

To the Editors:

Since Candide is anything but a “courtly” novel, Mr. Furbank’s assumption that I have tried “an experiment” in lowering the book’s tone is both untrue and irrelevant [“Cultivating Voltaire’s Garden,” NYR, December 15, 2005]. Others have found my translation “sprightly, intelligent…clear, idiomatic, even elegant” (Gita May). And it has been noted that, this being the tenth book I have translated from French, I have the capacity “necessary to take us on and along the satirical road of Voltaire’s Candide” (Mary Ann Caws).

Errors are regrettable; they are also inevitable. Hunting for lexical errors of limited significance is a sport of small utility. It is certainly true, and regrettable, that I fumbled the meaning of commère, turning “fellow godparent” into “godchild of his godmother.” But is this a matter of high importance? I am not persuaded by Mr. Furbank that “Ce n’est pas ma main qu’il faut baiser,” the old woman’s response to Candide’s overflowing gratitude, is indeed a bawdy pun, focused on the lady’s missing buttock. Candide’s patronne, she is saying, is not her, but someone else. My translation is correct, Mr. Furbank’s is wrong.

I erred, and should not have (the French is in no way difficult), about where the ex-mistress poisoned the old woman’s fiancé—but is this of high significance? Poison can be and has been readily administered in any location. Again, it is better to make no mistakes, but this one is so distinctly minor that no reader of my translation will be misinformed about the dirty deed, which is very significant indeed.

Finally, Mr. Furbank apparently forgets that Candide is a novel, not a philosophical tract. Voltaire fulsomely details Candide’s loss of innocence and acquisition of good, sober sense. When therefore Candide trumps philosopher Pangloss by insisting, in the book’s final words, that Cela est bien dit, “That’s well said,” mais il faut cultiver notre jardin, “but we need to work our fields,” the overwhelmingly clear point being made is that idealistic verbiage is totally inadequate for dealing with the real world. This is a statement which reverberates, to be sure, into a generalization—but it remains primarily aimed at Pangloss and all those who approach life as he does. One can deplore the fact that in the eighteenth century “garden” was identical to eighteenth-century French jardin, and that in modern English “garden” has taken on a very different meaning. But nostalgia over linguistic change should not be an excuse for linguistic error.

My correction of jardin’s longstanding mistranslation, here, as “garden,” is reinforced by cultiver, which in both Voltaire’s French and our English means “to bestow labor upon land in order to raise crops.” I have therefore translated cultiver as “work [the] fields.” To say as Mr. Furbank does that “the metaphorical meaning requires the word ‘cultivate'” is to ignore the fact that cultiver did not acquire the modern sense of “enlightening” until a full century after Candide was written.

Mr. Furbank’s “instinctive” rejection of linguistic reality would be abhorrent to Voltaire. “We need to work our fields” is precisely and exactly what he has said, and he, not Mr. Furbank, wrote the book.

Burton Raffel

Lafayette, Louisiana

P.N. Furbank replies:

I am afraid I do not feel that Burton Raffel’s letter is at all convincing. In regard to the old woman’s remark “Ce n’est pas ma main qu’il faut baiser,” he forgets that in English the difference between “It is not my hand you ought to be kissing” (but someone else’s) and “It is not my hand that you ought to be kissing” (but another part of my body)—which is the meaning here—can be indicated perfectly clearly by stress, but French does not use stress in this way and depends merely upon word order. In the circumstances, the old woman’s remark makes an excellent and very cogent joke. As for Mr. Raffel’s assertion that “cultiver did not acquire the modern sense of ‘enlightening’ until a full century after Candide was written,” I would refer him to a sentence in Voltaire’s L’Éducation des filles (1761), “ma mère m’a toujours regardée comme un être pensant dont il fallait cultiver l’âme,” which shows him using the word in a decidedly nonagricultural sense.

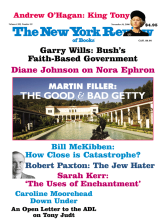

This Issue

November 16, 2006