In his formal acceptance of the Republican Party’s presidential nomination in 1868, General Ulysses S. Grant concluded with four words that struck a deep chord with voters: “Let us have peace.”1 For more than twenty years the country had been racked by conflict over slavery and its aftermath: fistfights in Congress, the clubbing to insensibility of an antislavery Massachusetts senator by a proslavery South Carolina congressman on the floor of the Senate, a small civil war between proslavery and antislavery settlers in Kansas Territory in which hundreds were killed, and John Brown’s Harpers Ferry raid, a failed effort to foment a slave uprising, had all foreshadowed the huge Civil War in which more than 620,000 Americans were killed. In the three years since that war ceased, a new political battle between president and Congress had culminated in the impeachment of Andrew Johnson and his escape from conviction by a single vote. General Grant had hoped that his generous surrender terms at Appomattox on April 9, 1865, would bring the bloodletting to an end. But the nation soon learned that the cessation of active war did not necessarily mean the inauguration of peace.

The American Civil War illustrated the famous aphorism of Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz that war is the continuation of politics by other means. In 1865 Americans would discover, as they did again in Iraq 138 years later, what we might describe as a corollary to Clausewitz: postwar reconstruction policy is a continuation of war by other (but distressingly similar) means. Violent resistance by ex-Confederates to the efforts of Congress to reconstruct the South on the basis of equal civil and political rights for freed slaves produced a level of “peacetime” violence unparalleled in American history until the Iraq adventure. In Louisiana alone, shadowy groups including one known as the Knights of the White Camellia killed more than two thousand people, most of them black, during the three years between Appomattox and Grant’s nomination for president. In several other states, terrorist guerrilla forces composed mainly of former Confederate soldiers and calling themselves by such names as the Ku Klux Klan killed hundreds more.2 Little wonder that people longed for surcease from constant strife and crisis. “Let us have peace,” echoed many newspapers when they published Grant’s acceptance letter. If anyone could win the peace, they hoped, it was the man who had won the war.

In 1870 and 1871 Congress enacted three laws to enforce the provisions of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments granting equal civil and political rights to freed people. Grant proceeded to enforce these laws with federal marshals and United States courts backed by federal troops if necessary. One of these laws (popularly called the Ku Klux Klan Act) gave the president authority to suspend the writ of habeas corpus in order to jail terrorists without trial in Southern states if he deemed it necessary. Mindful of opposition charges of military dictatorship and “Caesarism,” Grant used this power sparingly. But his administration did take strong action in 1871 and 1872 to break up the Klan. Federal marshals and troops arrested thousands of alleged Klansmen. Hundreds of others fled their homes to escape arrest. Federal grand juries handed down more than three thousand indictments. Several hundred defendants pleaded guilty in return for suspended or light sentences. The Justice Department (established in 1870) dropped charges against nearly two thousand others to clear clogged court dockets for trials of major offenders. About six hundred of these were convicted and 250 acquitted. Of those convicted, most received fines or light jail sentences, but sixty-five were imprisoned for up to ten years in the federal penitentiary at Albany, New York.3

The government’s main purpose in this crackdown was to destroy the Klan and restore a semblance of law and order in the South rather than to secure mass convictions. Thus the courts granted clemency to many convicted defendants and Grant used his pardoning power liberally. By 1875 all of the imprisoned men had served out their sentences or received pardons. The government’s vigorous action in 1871 and 1872 did bring at least a temporary peace to large parts of the former Confederacy. As a consequence, blacks voted in solid numbers and the 1872 election was the fairest and most democratic presidential election in the South until 1968.

This experience confirmed a reality that had existed since 1865: while counter-Reconstruction guerrillas assaulted unarmed black and white Republicans as well as teachers in freedpeople’s schools and the militias organized by Reconstruction state governments, they carefully avoided conflict with federal troops. Yet the success of federal enforcement in 1871 and 1872 contained seeds of future failure. Southern whites and Northern Democrats hurled charges of “bayonet rule” against the Grant administration. Southern Democrats learned that the Klan’s tactics of terrorism—midnight assassinations and whippings by disguised vigilantes operating in secret organizations—were likely to bring down the heavy hand of federal retaliation. They did not forswear violence, but openly formed organizations that they described as “social clubs”—which just happened to be armed to the teeth. Professing to organize only for self-defense against black militias, carpetbagger corruption, and other such bugbears of Southern white propaganda, they named themselves White Leagues (Louisiana), White Liners or Rifle Clubs (Mississippi), or Red Shirts (South Carolina). They were, in fact, paramilitary organizations that functioned as armed auxiliaries of the Democratic Party in Southern states in their drive to “redeem” the South from “black and tan Negro-Carpetbag rule.”

Advertisement

Nicholas Lemann’s Redemption focuses mainly on how this story played out in Mississippi, but he ranges over other deep South states as well, especially Louisiana. As he correctly points out, most of these paramilitaries—like those who had been Klan members—were Confederate veterans. Another study of the White League in Louisiana, also published this year, carefully analyzes the membership of this order in New Orleans and finds that 88 percent of its officers “can be positively identified as Confederate veterans who served in Louisiana units during the Civil War.”4 But they were not eager to reprise the war of 1861–1865, so they too were careful to avoid conflict with the dwindling number of federal troops stationed in the South and to portray their increasingly murderous attacks on blacks and Republicans as purely defensive.

The most notorious such confrontation occurred in 1873 at Colfax on the Red River in the plantation country of central Louisiana. Colfax was the parish seat of Grant Parish, whose population was almost equally divided between whites and blacks. Disputed elections had left rival claimants for control of both the state and the parish governments. Simmering warfare between the White League and the black militia came to a head in Colfax on Easter Sunday 1873. Claiming that “Negro rule” in the parish had produced corruption, pillage, and rape, the White League vowed to reassert white rule. Occupation of the courthouse by armed blacks provoked whites into a frenzy. “As vivid as the whites’ ideas about a coming Negro general assault were,” writes Lemann,

Negroes actually made no unprovoked, proven attacks on whites during this period. All they had definitely done by force was to take over the courthouse to which they had a right by gubernatorial proclamation…. It was the whites who openly treated one political party’s assumption of the powers of local government as provocation sufficient to go to war.

On April 13 nearly three hundred armed whites rode into Colfax pulling a cannon on a farm wagon. Using tactics learned as Confederate soldiers, they attacked the courthouse from three directions. After shooting down in cold blood several blacks trying to escape, they set the courthouse on fire, burning several men alive and killing the rest as they marched out in surrender. At least seventy-one blacks (by some accounts as many as three hundred) and three whites were killed—two of the latter by shots from their own side. Federal troops coming upriver from New Orleans arrived in time only to count the dead.

A federal grand jury indicted seventy-two whites under the Enforcement Act of 1870 for violating black civil rights. Only nine came to trial and three were convicted. These three went free in 1876 when the Supreme Court ruled (United States v. Cruikshank) that the Enforcement Act was unconstitutional because the Fourteenth Amendment prohibited only states, not individuals, from violating civil rights. “The power of Congress…to legislate for the enforcement of such a guaranty,” declared the Court, “does not extend to the passage of laws for the suppression of ordinary crime within the States…. That duty was originally assumed by the States and it still remains there.”5 The Court failed to say what recourse victims might have if a state did not or could not suppress such crimes.

In Louisiana and Mississippi, White Leaguers and White Liners carried on their campaigns of intimidation and murder with little regard for either federal or state courts. Federal troops were too few or too late to protect most targets of this violence. Tensions rose as the 1874 elections approached. The White League in Red River Parish southeast of Shreveport forced six white Republicans to resign their offices on pain of death—and then brutally murdered them after they had resigned. “For many former Confederates, this was a glorious time,” writes Lemann.

After years of defeat and loss of power and control, it looked as if they might be winning again…. They were taking their homeland back from what they saw as a formidable misalliance of the federal government and the Negro. The drama of it was so powerful that killing defenseless people registered in their minds as acts of bravery, and refusal to obey laws that protected other people’s rights registered as acts of high principle.

On September 14, two weeks after the Red River Parish murders, New Orleans became the scene of a battle between the White League on one side and the police and state militia on the other. The commander of the state forces (which included both black and white militia units) was none other than former Confederate General James Longstreet, who had become a Republican after the war and was now fighting against men who had once fought under him. Longstreet’s little army killed twenty-one White Leaguers and wounded nineteen, but suffered eleven killed and sixty wounded (including Longstreet) while being routed by the White Leaguers. The latter installed their own claimant to the governorship (from the disputed election of 1872), but President Grant promptly put an end to this tactic. Three regiments of US infantry and a battery of artillery arrived in New Orleans (then the state capital) supported by a flotilla of gunboats anchored in the river with a full complement of marines. “New Orleans became host to the largest garrison of federal troops in the United States,” writes the historian of these events, “and assumed the appearance of an occupied city, much as it had during the Civil War.”6 The soldiers ensured a fair election in the city. Grant also sent part of the Seventh Cavalry (George Armstrong Custer’s regiment) to patrol the turbulent Red River parishes.

Advertisement

Grant ordered to Louisiana his top field commander, General Philip H. Sheridan. This hotheaded fighter had pulled no punches in his Civil War career, nor did he now. “I think that the terrorism now existing in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas could be entirely removed, and confidence and fair dealing be established, by the arrest and trial of the ringleaders of the armed White Leagues,” Sheridan wired the secretary of war in a dispatch that was widely published in the press.

If Congress would pass a bill declaring them banditti, they could be tried by a military commission. The ringleaders of this banditti, who murdered men here on the 14th of last September, and also more recently at Vicksburg, Miss., should, in justice to law and order, and the peace and prosperity of this southern part of the country, be punished. It is possible that if the President would issue a proclamation declaring them banditti, no further action need be taken except that which would devolve on me.

We shall never know if Sheridan’s approach would have worked, for it was not tried. His banditti dispatch provoked a firestorm of condemnation in the North as well as the South. Instead of bringing peace, Grant’s Southern policy seemed to be causing even more turmoil. Many Northerners adopted a “plague on both your houses” attitude toward the White Leagues and the “Negro-Carpetbag” state governments. Withdraw the federal troops, they said, and let the Southern people work out their own problems even if that meant a solid South for the white-supremacy Democratic Party. Benefiting from this sentiment as well as from an anti-Republican backlash caused by an economic depression that followed the Panic of 1873, Democrats gained control of the House of Representatives and several Northern governorships in 1874 for the first time in almost two decades. And the Supreme Court was already sending signals that it would strip the 1870–1871 enforcement laws of their teeth.

Mississippi’s Republican state government became a victim of this new climate of opinion. Of all the Reconstruction governments, Mississippi’s was one of the most honest and efficient. And of all the “carpetbagger” senators and governors, Adelbert Ames was one of the most able, effective, and idealistic. Few carpetbaggers fit the nefarious stereotype of the genre, and Ames fit it least of all. Graduating near the top of his West Point class of 1861, this native of Maine fought in most of the battles of the eastern theater in the Civil War, received the Medal of Honor, and was promoted to brevet major general in the regular US Army in 1865 at the age of twenty-nine. After commanding the military district of Mississippi and Arkansas, and shepherding these states back into the Union, Ames was elected senator from Mississippi in 1870 and governor in 1873. His experiences produced a deep and genuine commitment to education and equal justice for the freedpeople.

Nicholas Lemann admires Ames, whose story of courageous but foredoomed tenure as governor of this black-majority state forms the backbone of Redemption. Lemann has immersed himself in the rich primary sources, especially the voluminous official and personal Ames papers. He has also mastered the large historical literature on Reconstruction, which has turned on its head the once-lurid portrait of this era as an orgy of misrule and exploitation of victimized Southern whites by cynical carpetbaggers, opportunistic scalawags, and barbaric blacks. In truth, the failure of Reconstruction to achieve its goals of racial justice and progress was a tragedy of classical proportions; Lemann’s eloquent narrative is equal to the significance of his subject.

To most whites in Mississippi it mattered little that the state government under Ames was relatively honest and efficient by standards of the time: it was not their government. Whites owned most of the property and thus paid most of the taxes; they resented the portion of those taxes that went to black schools. The black majority sustained Republican county and state governments for which very few whites had voted. Elections for the state legislature were scheduled for 1875. The White Line rifle clubs were determined, as they expressed it, to “carry the elections peacefully if we can, forcibly if we must.” Their strategy became known as the Mississippi Plan.

Part of this plan involved economic coercion of black sharecroppers and laborers, who were informed that if they voted Republican they could expect no further work. But violence, threatened and actual, was the main component of the Mississippi Plan. White Liners discovered that their best tactic was the “riot.” When Republicans held a political rally, several White Liners would attend with concealed weapons and others would lurk nearby in reserve. Someone would provoke a shoving or heckling incident; someone else would fire a shot—always attributed to a Republican—whereupon all hell would break loose. When the shooting finally stopped, black and Republican casualties always outnumbered White Liner casualties by at least twenty to one. Then the White Liners would ride out into the countryside and shoot down any black man they suspected of political activism—and sometimes his family as well. Several years later one White Liner candidly confessed that

the question which presented itself then to the people of Hinds County was whether or not the negroes, under the reconstruction laws, should rule the county…. Throughout the countryside for several days the negro leaders, some white and some black, were hunted down and killed, until the negro population which had dominated the white people for so many years was whipped.

Lemann points out that “the only way for Republicans to ensure that Negroes would be able to organize to vote in November…was through the same kind of military force the Democrats were using.” But the arming of black militia would play into the hands of white propagandists who spouted endlessly about savage Africans murdering white men and raping their women. Moreover, writes Lemann, “any black militia would be outnumbered and outarmed by the shadowy white force now in place all over the state.” The only solution was federal troops. Ames sent an urgent message to Washington requesting them. Grant meant to comply, and instructed his attorney general to prepare a proclamation ordering lawless persons to cease and desist—a necessary prelude to sending troops—but also to urge Ames “to strengthen his position by exhausting his own resources in restoring order before he receives govt. aid.”

The attorney general, a conservative Republican, goaded Ames more than Grant intended. “The whole public are tired out with these annual autumnal outbreaks in the South,” wrote the nation’s chief law enforcement officer, “and the great majority are now ready to condemn any interference on the part of the government…. Preserve the peace by the forces in your own state, and let the country see that the citizens of Mississippi, who are…largely Republican, have the courage to fight for their rights.”7 No federal troops came.

Ames did organize a few companies of black militia, even though he recognized that to use them in combat against the heavily armed Confederate veterans in the rifle clubs “precipitates a war of races and one to be felt over the entire South.” To avoid such a result, Ames negotiated an agreement with Democratic leaders whereby the latter promised peace in return for disarmament of the militia. “No matter if they are going to carry the State,” said Ames wearily, “let them carry it, and let us be at peace and have no more killing.”8 Violence and intimidation continued under this “peace agreement,” however, and on election day black voters were conspicuously absent from the polls. In five counties with large black majorities, Republicans polled twelve, seven, four, two, and zero votes respectively. In this way a Republican majority of 30,000 at the previous election became a Democratic majority of 30,000 in 1875.

The Mississippi Plan worked so well that other Southern states carried out their own versions of it in the national election of 1876. The last Republican state governments in the South collapsed when President Rutherford B. Hayes withdrew all federal troops in 1877. Democrats had “redeemed” the South, which remained solid for their party and for white supremacy for almost a century. “Reconstruction, which had wound up producing a lower-intensity continuation of the Civil War, was over,” concludes Lemann. “The South had won. And the events in Mississippi in 1875 had been the decisive battle.” A recent study of the Republican Party and Reconstruction agrees that the “egregious violence” of unreconstructed Southern whites eventually prevailed over efforts to enforce equal rights in the South. The author marks the end of this era in 1894, when Democrats controlled the presidency and both houses of Congress for the first time since 1859 and promptly repealed the enforcement legislation of 1870 and 1871. But the author’s assertion that with this act “white southerners had won their long twilight struggle to undo the results of the Civil War” is dead wrong.9 Those results were the preservation of the United States as one nation and the abolition of slavery. They have not been reversed. It was federal enforcement of Reconstruction, not the results of the Civil War, that was overturned in 1877 and buried in 1894. Not until another Republican president—who like Grant also happened to be a famous general—sent federal troops back into the South in 1957 to launch the second Reconstruction did the promises of the first one begin the long journey toward fulfillment.

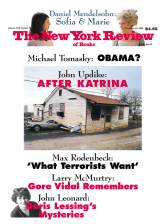

This Issue

November 30, 2006

-

1

The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, edited by John Y. Simon et al., 28 volumes to date (Southern Illinois University Press, 1967– ), Vol. 18, p. 264.

↩ -

2

See James K. Hogue, Uncivil War: Five New Orleans Street Battles and the Rise and Fall of Radical Reconstruction (Louisiana State University Press, 2006); Gilles Vandal, Rethinking Southern Violence: Homicides in Post– Civil War Louisiana, 1866–1884 (Ohio State University Press, 2000); Allen W. Trelease, White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction (Harper and Row, 1971); George C. Rable, But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction (University of Georgia Press, 1984).

↩ -

3

See Everette Swinney, “Enforcing the Fifteenth Amendment,” Journal of Southern History, Vol. 28, No. 2 (May 1962); Robert J. Kaczorowski, The Politics of Judicial Interpretation: The Federal Courts, Department of Justice and Civil Rights, 1866–1876 (Oceana, 1985); Lou Falkner Williams, The Great South Carolina Ku Klux Klan Trials, 1871–1872 (University of Georgia Press, 1996).

↩ -

4

Hogue, Uncivil War, p. 130.

↩ -

5

25 Fed. Cas. 707, p. 210; 92 U.S. Reports, p. 542.

↩ -

6

Hogue, Uncivil War, p. 145.

↩ -

7

Richard N. Current, Three Carpetbag Governors (Louisiana State University Press, 1967), p. 88.

↩ -

8

“Mississippi in 1875: Report of the Select Committee to Inquire into the Mississippi Election of 1875,” Senate Report no. 527, 44 Congress, 1 Session (Government Printing Office, 1876), p. 1807.

↩ -

9

Charles W. Calhoun, Conceiving a New Republic: The Republican Party and Reconstruction, 1869–1900 (University Press of Kansas, 2006), pp. 7, 274.

↩