1.

In the Western imagination, Istanbul, alias Constantinople, was once identified with decay, corruption, and imperial decline as well as with voluptuous pleasure. Flaubert longed to visit and buy himself a slave. During the nineteenth century, the city was the capital of a shrinking Ottoman Empire, the “Sick Man of Europe.” After World War I, it lost its political importance and became a provincial outpost when the capital was moved to Ankara. Turks complained that very few people came to visit. In the following decades, Istanbul grew less exotic as the result of accelerated Westernization and the radical measures of the Republic of Turkey’s founder and first president, Kemal Atatürk: the banishing of the sultan, the closing of the famous harem, the introduction of Latin script, the prohibition of Islamic head coverings, the burning or deliberate demolition of many ancient wooden mansions.

After World War II the city was periodically torn by anarchy, civil strife, and brutal military coups by generals who claimed they wanted to “restore democracy.” In 1960, Adnan Menderes, an elected prime minister, and two of his ministers were put on trial and subsequently hanged on charges—later challenged—of instigating a pogrom against the city’s Greek population in 1955. The decline continued into the 1980s, a period in which there were fears of imminent economic collapse. I remember landing at Istanbul airport on a cold winter morning early in 1981, shortly before yet another brutal military coup. The terminal was unheated and unkempt. One of the great glass windows was smashed; an icy wind blew in and drove loose rubbish across the stone floor. Because of the scarcity of fuel, there were no taxis. Turkey was said to be on the verge of national bankruptcy. The headline in one of the local papers claimed that currency reserves were down to $9 million, less than the daily cost of maintaining Turkey’s scarce fuel supplies.

In the city, electricity was turned off intermittently during the day and night. That evening I met with a foreign diplomat at his home high up on a cliff overlooking the Bosphorus. From his veranda there was a magnificent panoramic view, across the straits to the Asian coast. In the west, towering over a panorama of flat roofs, Hagia Sophia and the great mosques were in full view, surrounded by pointed white minarets, slim and elegant as daggers. They were dramatically illuminated against a darkening sky. I can think of no other great city with so magnificent a setting, whether approached from the glimmering Sea of Marmara, as the armies of the Fourth Crusade did when they sacked the Byzantine city in 1204, or from the nearby Asian coast across the narrow straits, as the Turks did two centuries later. “There are places where history is inescapable, like a highway accident,” Joseph Brodsky wrote about Istanbul; its “geography provokes history.”1

Dusk is often gloomy in Istanbul, especially in winter. Below us, down in the straits, thin wisps of smoke rose from a ferry boat, swirling up in circles and loops like the old Arabic script abolished in 1928 by Kemal Atatürk. I won’t forget the moment when, as we stood on the narrow veranda, the lights suddenly dimmed again and went out without warning, as they often did in those days. The fabled view became pitch dark, first to the west, then the darkness spread across the Golden Horn and soon everywhere else. It was a rare moment when one could actually see the lights go out simultaneously in both Europe and Asia.

At the time we tended to overdramatize such a coincidence. My host, a civilized man with a sense of irony sharpened by years of service in difficult countries, made apocalyptic jokes about it. The year 1981 was, after all, a high point in the cold war. The Soviet Union had just invaded Afghanistan, the first time since 1945 that it had militarily transgressed the lines of the Yalta Agreement. Worse was expected. A short while after the lights went out, a Soviet aircraft carrier followed by two destroyers, brilliantly lit up, entered the great darkness below, majestically sailing, in Brodsky’s words, from the First Rome, through the Second, on their way to the Third.

2.

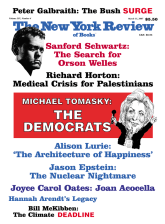

In Istanbul: Memories and the City, Orhan Pamuk, the recent winner of the Nobel Prize in literature, draws a brilliant portrait of the city which has long infused his imagination. He is the author also of Snow, The Black Book, and other haunting novels that seem peculiarly relevant at a time when there is much talk of a clash of civilizations and Turkey has been campaigning unsuccessfully for membership in the European Union. Pamuk is a secular-minded Turk, said to have been the first Muslim to condemn the fatwa against Salman Rushdie. He is renowned also for his courage in publicly acknowledging that a million Armenians were killed by the Turks during World War I and at least 30,000 Kurds at a later date. “Hardly anyone here dares to say it,” he told a Swiss magazine in 2005. “So I do, and they hate me for it.”2 He was risking a prison sentence of up to three years for violating paragraph 301 of the Turkish criminal code, which outlaws the “public denunciation of Turkishness.” Some forty Turks have been charged under this paragraph in recent years. Were it not for Turkey’s continuing efforts to join the European Union, he, too, would probably have been tried under the same law; now he is also protected by the Nobel Prize.

Advertisement

When Pamuk was born, in 1952, Istanbul’s population was a little more than half a million. There were no high-rise buildings to block the famous views. By 2000 the city had grown to ten million. Tall buildings and thick clouds of air pollution now dominate the horizons. The Golden Horn has become a smelly sewer. In the vast suburbs that surround the city, the super-rich barricade themselves behind high barbed-wire fences, fearful of the millions of newly arrived wretched and poor from the Anatolian highlands.

There was a time many years ago, Pamuk says, when he dreamed of writing a great novel about Istanbul. Instead, in this recent book he reinvents the Istanbul of his childhood and constructs a moving, at times spectral, portrait of his city. “These are the sad joys of black-and-white Istanbul,” he writes in one characteristic passage,

the crumbling fountains that haven’t worked for centuries; the poor quarters with their forgotten mosques; the sudden crowds of schoolchildren in white-collared black smocks; the old and tired mud-covered trucks; the little grocery stores darkened by age, dust, and lack of custom; the dilapidated little neighborhood shops packed with despondent unemployed men; the crumbling city walls like so many upended cobblestone streets; the entrances to cinemas that begin, after a while, to look identical; the pudding shops; the newspaper hawkers on the pavement; the drunks that roam in the middle of the night; the pale streetlamps; the ferries going up and down the Bosphorus and the smoke rising from their chimneys; the city blanketed in snow.

He still lives in the same modern five-story building where he was born, the Pamuk Apartments, which had been built in the early twentieth century to house several branches of the Pamuk family. As a photograph in the book shows, his mother held him up on one of the fourth-floor balconies, where he then lived, to “show me the world.” Pamuk now occupies the penthouse and likes to think that much of the world can still be seen from there.

He was born, he writes, into a troubled, upper-middle-class, nouveau riche family. His parents, first-generation “Westernized” Turks, quarreled incessantly. His father disappeared intermittently, and sometimes his mother did as well. One of his grandfathers had left a fortune so large that his father and uncles never managed to finish it off completely through high living and disastrous investments. The Pamuk Apartments were occupied mostly by members of the extended family, uncles and aunts and an elderly grandmother, who resembled a languid figure in a Renoir painting. The house stood at the edge of the former gardens of Nisantasi, where, during the late Ottoman Empire, some of the pashas and viziers had moved and built magnificent wooden mansions with fancy high windows and beautifully carved wooden beams and eaves. By the time of Pamuk’s youth they had fallen into disrepair and were being torn down one by one. “My first schools,” he writes,

were housed in the Crown Prince Yusuf I·zzeddin Pasha Mansion, and in the Grand Vizier Halil Rifat Pasha Mansion. Each would be burned and demolished while I was studying there, even as I played soccer in the gardens. Across the street from our home, another apartment building was built on the ruins of the Secretary of Ceremonies Faik Bey Mansion…. The rest—those mansions where Ottoman officials had once entertained foreign emissaries and those that belonged to the nineteenth-century Sultan Abdülhamit’s daughters—I recall only as dilapidated brick shells with gaping windows and broken staircases darkened by bracken and untended fig trees; to remember them is to feel the deep sadness they evoked in me as a young child. By the late fifties, most of them had been burned down or demolished to make way for apartment buildings.

Most of the still-remaining wooden houses are decrepit and abandoned to this day.

As a boy, Pamuk had the run of his entire building. His parents, uncles, and aunts were proud of the new Westernized Turkey under Atatürk. Religion was said to be for the servants. If his grandmother discovered that a repairman she had summoned had gone off to pray, she would say sharply that such “traditions and practices” were impeding “our national progress.” A grand piano could be found on each floor of the house, but no one ever played them. In each flat there was a locked glass cabinet displaying teacups, sugar bowls, snuff-boxes, and similar European knickknacks that no one ever touched. “Sitting rooms were not meant to be places where you could lounge comfortably,” he writes; “they were little museums designed to demonstrate to a hypothetical visitor that the householders were westernized.”

Advertisement

Only with the arrival of television sets in the 1970s, Pamuk says, did such manifestations of class go out of fashion among the Istanbul bourgeoisie. There also were massive desks inlaid with mother of pearl at which no one, except young Orhan, ever sat and Art Nouveau screens behind which nothing was hidden:

A person who was not fasting during Ramadan would perhaps suffer fewer pangs of conscience among these glass cupboards and dead pianos than he might if he were still sitting cross-legged in a room full of cushions and divans.

And he would await sunset with as much hunger as those keeping the fast:

In the secular fury of Atatürk’s new Republic, to move away from religion was to be modern and western; it was a smugness in which there flickered from time to time the flame of idealism. But that was in public. In private life, nothing came to fill the spiritual void. Cleansed of religion, home became as empty as the city’s ruined yal?s and as gloomy as the fern-darkened gardens surrounding them.

3.

Walter Benjamin once wrote that in observing a city, outsiders concentrate mostly on the exotic and picturesque, while the natives always see the place through layers of memory. Gérard de Nerval, Théophile Gautier, and Gustave Flaubert are Pamuk’s main foreign literary witnesses. Flaubert was the first to note that the gravestones one saw throughout the city (and still occasionally sees today) recalled the dead themselves, slowly sinking into the earth as they aged and soon to vanish without a trace. Western writers found the crumbling houses and the ruins charming. For the city’s more thoughtful residents, Pamuk claims, they were reminders that the city was so poor and confused that it could never dream of rising to its former wealth, power, and culture. It is still no more possible to take pride in the neglected dwellings where “dirt, dust and mud have blended into their surroundings than it is to rejoice in the beautiful old wooden houses that as a child I watched burn down one by one.” Even when he disagrees with what some outsiders have written, Pamuk says they can give him pleasure, “in no small part because the picture helps me fend off narrow nationalism and pressures to conform.”

Four prominent twentieth-century writers who have written extensively about the city are Pamuk’s main Turkish witnesses—the poet Yahya Kemal, the historian Res��at Ekrem Koçu, the novelist Ahmed Hamdi Tanp?nar, and the author of memoirs Abdülhak ��Sinasi Hisar. With them, he claims, he has maintained an intensive, lifelong debate. Istanbul: Memories and the City is intensely personal, in some way Pamuk’s own, real-life bildungsroman. Mixing personal reminiscence with literary criticism and metaphysical musings, Pamuk turns the book into an intimate memoir. He was a moody, precocious youngster who for years wavered between painting and writing. His mother warned him against becoming a painter; Istanbul was not Paris, she said. The mood and melancholy of Istanbul in those days is wonderfully reflected in Pamuk’s spare prose as well as in a series of remarkable black-and-white photographs, mostly by Ara Güler, that accompany it. Istanbul is a very sensual book, evoking smells, tastes, sounds, and a series of stunning sights in the city and along the Bosphorus that, as a boy, he could observe from his fourth-floor windows only through the gaps between ugly cement apartment houses. The translator, Maureen Freely, renders Pamuk’s Turkish into startlingly evocative English prose, with a distinctly painterly touch. Pamuk was trained as an architect and struggled to paint before deciding in his early twenties to be a writer. Long before this decision, he writes, he would walk for many hours on the uneven pavements throughout the city

past streetlamps with pale lights or none at all, to the melancholy of the narrow cobblestone alleys, and there I would enjoy a perverted happiness at belonging to such a sorrowful, dirty, and impoverished place…. Painting allowed me to enter the scene on the canvas.

Today, he says, the residents of the city are slightly uneasy about what the foreigner might see in the crumbling old houses lining miserable narrow streets and yet the houses are important for understanding the city’s melancholy, its so-called hüzün. It is the word that best describes the sadness of a place that has experienced a century of defeat and decline, and Pamuk devotes a chapter to discussing its layered meanings. The root of the word hüzün, he observes, is Arabic; in the Koran it describes Muhammad’s pain upon the loss of his wife Hatice and his uncle Ebu Talip. The low point of Istanbul’s hüzün was apparently at the end of World War I when British, French, and Italian warships were anchored in the strait outside the sultan’s palace. After World War I broke up the Hapsburg Empire, the people of Vienna are known to have fostered a similar phase of melancholy and self-pity, but the old Vienna survives mainly in a form of self-irony, reflected in the fictions of such writers as Joseph Roth and Robert Musil. There is little irony in Pamuk’s book. As he writes of his bourgeois Istanbul upbringing:

the melancholy of this dying culture was all around us. Great as the desire to westernize and modernize may have been, the more desperate wish was probably to be rid of all the bitter memories of the fallen empire, rather as a spurned lover throws away his lost beloved’s clothes, possessions, and photographs. But as nothing, western or local, came to fill the void, the great drive to westernize amounted mostly to the erasure of the past; the effect on culture was reductive and stunting.

The hüzün over the loss of the old Ottoman Empire, Pamuk claims, has marked Turkish letters for almost a century and has come to stand for “worldly failure, listlessness, and spiritual suffering,” though the expression has suffered from overuse and misuse during that time. To understand the impact of hüzün on Turkish poetry and how it came to dominate Istanbul’s popular music, it is not enough to grasp the history of the word, he maintains: one must describe the history of the city following the destruction of the Ottoman Empire and—“even more important”—the way this history is reflected in the city’s landscapes and its people:

To feel this hüzün is to see the scenes, evoke the memories, in which the city itself becomes the very illustration, the very essence, of hüzün. I am speaking of the evenings when the sun sets early, of the fathers under the streetlamps in the back streets returning home carrying plastic bags. Of the old Bosphorus ferries moored to deserted stations in the middle of winter, where sleepy sailors scrub the decks, pail in hand and one eye on the black-and-white television in the distance; of the old booksellers who lurch from one financial crisis to the next and then wait shivering all day for a customer to appear; of the barbers who complain that men don’t shave as much after an economic crisis;…of the patient pimps striding up and down the city’s greatest square on summer evenings in search of one last drunken tourist; of the broken seesaws in empty parks….

The hüzün of Istanbul is not just “the mood evoked by its music and its poetry, it is a way looking at life that implicates us all,…a state of mind that is ultimately as life-affirming as it is negating.” It is associated not just with death and loss but also with anger, he says, with rancor, love, and groundless fear, a state of mind somewhat akin to that suggested by Robert Burton in The Anatomy of Melancholy. The difference is that hüzün is a collective mood: it reflects the fragility of people’s lives in Istanbul, the way they treat one another but also “the distance they feel from the centers of the West.” For all the modern façades the visitor may encounter today, for all the energy that recently made possible the protest march of some 50,000 people at the murder of an Armenian editor, there may be a certain affinity, in Pamuk’s view, between hüzün and the melancholy described by Claude Lévi-Strauss in Tristes Tropiques. “The difference lies in the fact,” he adds,

that in Istanbul the remains of a glorious past civilization are everywhere visible. No matter how ill-kept, no matter how neglected or hemmed in by concrete monstrosities, the great mosques and other monuments of the city, as well as the lesser detritus of empire in every side street and corner—the little arches, fountains and neighborhood mosques—inflict heartache on all who live among them.

Pamuk is struck by the fact that 102 years before he was born, Flaubert passed through town and rashly predicted that in a century’s time it would be the capital of the world.

The reverse came true: After the Ottoman Empire collapsed, the world almost forgot that Istanbul existed. The city into which I was born was poorer, shabbier, and more isolated than it had been before in its two-thousand-year history….

Pamuk deplores the deliberate ethnic cleansing of Istanbul’s minority groups during the last century. Istanbul has become a “monotonously monolingual city in black and white.” Early in the twentieth century, he says, only half the city’s population were Muslims; most of the rest were the descendants of Byzantine Greeks. In the Fifties, when he grew up, there were still sizable Greek, Armenian, Circassian, Jewish, and other minority communities. They are mostly gone nowadays. When the British departure from Cyprus in 1955 resulted in a standoff between Greece and Turkey over control of the island, the Turkish government deliberately provoked a pogrom in Istanbul—what one might call “conquest fever”—against its Greek Orthodox minority, by allowing mobs to rampage through the city, sacking Greek and Armenian shops, raping women, murdering priests, and destroying churches. The rioters, Pamuk writes,

were as merciless as the soldiers who sacked the city after it fell to Mehmet the Conqueror…. [Their] terror raged for two days and made the city more hellish than the worst orientalist nightmares…. [It] had the state’s support.

In addition to Pamuk’s accomplishments as a novelist, his liberalism as a defender of human rights and as the advocate of a free, open society in Turkey was apparently an additional reason for the decision to award him this year’s Nobel Prize. But Istanbul goes beyond an account of deprivations of rights. By evoking the gradual changes in the cityscape, and in the very faces of the people of Istanbul, Pamuk exposes the decline—but not the fall—of a great city.

This Issue

March 15, 2007