Today we expect nonfiction to be either comic or somber: to make us laugh, or to inform us, warn us, or terrify us with accounts of miserable childhoods or natural and political disasters. The idea that prose might be both casual in manner and serious in intent is almost forgotten. It survives, however, in the work of Alain de Botton. In the last decade he has considered—in books whose brevity and informal tone disguise the occasional gravity of their content—travel, love, literature, philosophy, and the value of reading. His best-known work, How Proust Can Change Your Life, is accurately described on its flyleaf as both a perceptive literary biography and a self-help manual.

The simplicity of his writing is not the product of a simple mind. De Botton, who was born in Zurich in 1969, has a double first from Cambridge in history and philosophy, and is now director of the graduate philosophy program at the University of London. His aversion to deliberately difficult scholarly prose, however, has always been intense. In The Consolations of Philosophy (2000) he remarked that “there are…no legitimate reasons why books in the humanities should be difficult or boring; wisdom does not require a specialized vocabulary or syntax.” He then quoted one of his favorite authors, Montaigne, who remarked over four hundred years ago that “the search for new expressions and little-known words derives from an adolescent schoolmasterish ambition.”

De Botton was a natural essayist from the start. The three novels that began his career, On Love (1993), The Romantic Movement (1994), and Kiss and Tell (1995), though cast as contemporary love stories, are essentially frames upon which to hang observations on various subjects, much as in the days before washing machines, colorful wet clothes were spread out on drying racks. Kiss and Tell, for instance, riffs on biography and autobiography, The Romantic Movement on sentimentality, fashion, interior decoration, unrequited love, and many other topics.

After this, de Botton’s books were openly presented as nonfiction. In The Consolations of Philosophy he explains how writers as different as Plato, Epicurus, Seneca, and Schopenhauer can relieve us of anxiety for the future and financial loss and comfort a broken heart. Perhaps somewhat ironically, he often recommends an attitude of philosophical detachment, remarking that

the Greek philosopher Pyrrho once travelled on a ship which ran into a fierce storm. All around him passengers began to panic…. But one passenger did not lose his composure and sat quietly in a corner, wearing a tranquil expression. He was a pig.

However, in a passage that suggests an atypical unfamiliarity with natural history, or an unusual erotic life, de Botton admits that detachment is not always possible under the influence of desire, which forces us

to abandon sensible plans in order to lie in bed with people, sweating and letting out intense sounds reminiscent of hyenas calling out to one another across the barren wastes of the American deserts.”1

De Botton’s The Art of Travel (2002) is a collection of entertaining and perceptive meditations on his subject, considered through the work of well-known writers: J.-K. Huysmans on the anticipation and rejection of travel, Baudelaire on ambivalence toward places, Flaubert on the attractions of the Orient, Wordsworth on the benevolent moral effects of nature, Burke on the sublime, and Ruskin on the importance of careful observation. Following Ruskin’s advice, de Botton observes and describes many different scenes, including a Caribbean beach, where at the edge of the sea he “could hear small lapping sounds beside me, as if a kindly monster was taking discreet sips of water from a large goblet.” In spite of his enthusiasm for certain destinations, de Botton is not altogether in favor of travel. He notes ruefully that one brings oneself along on every journey, and that after a quarrel with a friend on this same beach he felt so disagreeable that he was even “insulted by the perfection of the weather.” In a Madrid hotel, surrounded by guidebooks that told him what to see and what to feel about it, he felt a strong wish to stay in bed and take the next flight home.

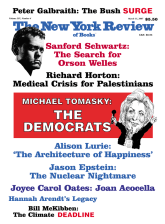

One difference between de Botton and most contemporary authors who write informally about serious topics (though seldom with so much originality and charm) is that he is not concerned with telling us how to make money, become famous, improve our health or appearance, or attract desirable mates. Nor does he wish to challenge or reinforce our social and political views. Instead, he hopes to make our lives happier and more interesting. This goal may be particularly relevant today: recently, according to The New York Times, there has been so much general discouragement and gloom, especially among the young, that several colleges and universities have introduced psychology courses whose avowed intent is to teach undergraduates to feel better about themselves and the world. De Botton’s new book, The Architecture of Happiness, would be a natural for the syllabi of these courses, since its basic aim is to show how buildings can affect and improve our lives.

Advertisement

De Botton’s attribution to architecture of not only cause but, by implication, conscious intent has interesting parallels. For young children, almost everything may seem alive and conscious: not only their own toys, but trees, trucks, tables, and TVs. The idea of objects having agency was also once common among adults: in the Middle Ages there are records of a court case in which a three-legged stool was tried and executed (appropriately, with an axe) for causing several people to trip over it and injure themselves. Even now we express similar ideas: you will hear someone say that his new Volvo is a real sweetie and never lets him down, or that her mean old computer is acting up again. If questioned, they would probably claim these statements are mere metaphors; but they are clearly the residue of a primitive, childlike way of thinking.

For some people, this cast of mind persists strongly and consciously into adulthood. Alain de Botton is as addicted to personification as any three-year-old or Romantic poet—or as his mentor in The Art of Travel, John Ruskin, who saw pine trees as “all comfortless…yet with such iron will,” and with a “dark energy of delicate life and monotony of enchanted pride.” In the Alps cows gaze at de Botton “with sad, almost wise eyes,” and a bridge over a gorge “seems unimpressed by the razor-sharp stones around it, by the childish moods of the river and the contorted, ugly grimaces of the rock-face.” In The Architecture of Happiness he makes explicit many of the vague impressions that we all sometimes have when we enter a building, impressions that were stronger—or at least more readily available to our conscious minds—when we were young.

As children, my friends and I often saw buildings as friendly or unfriendly, comforting or threatening. Almost every suburban neighborhood had a “haunted house” that we dared each other to approach on Halloween: often a house in the Victorian Gothic style made famous by Charles Addams’s New Yorker cartoons. There was also a generic type of benevolent dwelling that appeared in our art, of the type that the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard speaks of in The Poetics of Space as “the picture most frequently drawn by the very young, that picture sometimes called the ‘Happy House.'”2 This is the image, familiar to almost every parent or teacher, of a square one- or two-story home with a peaked roof, a central door, and two or more symmetrically placed windows that may sometimes suggest a face with eyes and a mouth. In cool climates the house often has a chimney with curls of smoke pouring out, suggesting that the building is warm and inhabited. Frequently the Happy House is surrounded by trees and/or flowers, and a big yellow sun shines in the sky, which is indicated by a strip of bright blue at the top of the drawing. According to Bachelard, unhappy or disturbed children will often produce a picture of an Unhappy House in which the sky is black, with no sun; these houses frequently have no windows, or only black squares in their place.

Alain de Botton believes (or perhaps partly affects to believe) in the Happy House. The Architecture of Happiness is a perceptive, thoughtful, original, and richly illustrated exercise in the dramatic personification of buildings of all sorts. De Botton suggests that houses may have moods: he speaks of a brick terraced house in London (possibly his own in Hammersmith) as a “dignified and seasoned creature” which when its inhabitants are away “gives signs of enjoying its emptiness. It is rearranging itself after the night, clearing its pipes and cracking its joints.” And structural consciousness, in his view, is not limited to domestic construction. Isambard Brunel’s famous Clifton Suspension Bridge in Bristol, England, for instance, with “its ponderous masonry and heavy steel chains,…has something to it of a stocky middle-aged man who hoists his trousers and loudly solicits the attention of others before making a jump between two points.”

For de Botton, almost every building not only has a character, it influences our own. We are, he writes, “for better or for worse, different people in different places.” Like the persons we meet, architecture can make us happy; but it can also, perhaps more often, make us miserable: “In a hotel room strangled by three motorways, or in a waste land of run-down tower blocks, our optimism and sense of purpose are liable to drain away.” Dirt, disorder, and failures of décor can also be deeply injurious. “What will we experience in a house with prison-like windows, stained carpet tiles and plastic curtains?” Clearly, we (or at least anyone reasonably sensitive and perceptive) will experience horror and dismay. Yet as de Botton points out, “we are never far from damp stains and cracked ceilings, shattered cities and rusting dockyards.” Even in Europe and America most people cannot afford to live in perfectly beautiful buildings. It is thus fortunate that we have “an urge to override our senses and numb ourselves to our settings,” and by averting our gaze from much of our built environment, avoid what he characterizes as “the possibility of permanent anguish.”

Advertisement

This sort of self-protective blindness is also necessary, de Botton implies, since it is possible to become too concerned about the perfection of one’s dwelling. There is, he says, “a genuine antithesis between…an attachment to beautiful architecture and the pursuit of an exuberant and affectionate family life.” (Indeed, anyone who reads architectural magazines or even the Home and Garden section of The New York Times will have seen many photos of interiors which strongly suggest that their owners prefer kidskin sofas to kids.)

As de Botton points out, ideas about what makes a building beautiful and benevolent change over time, swinging “between the restrained and the exuberant; the rustic and the urban; the feminine and the masculine.” In Europe, from the Renaissance on, an ideal structure was often classical Greek or Roman in inspiration: usually adapted to the local landscape and climate, but always featuring classical columns, pediments, arches, and/or statuary. In the eighteenth century, however, Gothic revival architecture gradually became fashionable, and by the early nineteenth century you could also order up a house in many exotic international and historical styles: Swiss, Indian, Chinese, Egyptian, Jacobean, etc.

For at least two hundred years, beginning in the seventeenth century, elaboration, variety, and decoration in architecture were admired. Eventually, however, there was a reaction, led at first by scientists and engineers. The use of iron framing and wide expanses of glass that made London’s Crystal Palace famous in the mid-nineteenth century gradually revolutionized construction and design. For early modern architects, all decoration was ugly and superfluous. Simplicity was beautiful, and

a structure was correct and honest in so far as it performed its mechanical functions efficiently; and false and immoral in so far as it was burdened with non-supporting pillars, decorative statues, frescos or carvings.

This connection between architecture and morality, as de Botton demonstrates, is not new. For centuries both architects and philosophers have claimed that beautiful buildings could make people virtuous as well as happy. In early Christian and Islamic theology,

attractive architecture was held to be a version of goodness…and its ugly counterpart, a material version of evil…. The moral equation between beauty and goodness lent to all architecture a new seriousness and importance.

In mid-nineteenth-century England, John Ruskin informed his readers that we should not want our buildings merely to shelter us; we should want them to speak to us “about…the kind of life that would most appropriately unfold within and around them.”

It was not only the exterior of a building that could be moral or immoral. According to Deborah Cohen’s interesting new study, Household Gods,

Urged on by clergymen who preached that beauty was holy, Victorians evaluated the merits of sideboards and chintzes according to a new standard of godliness. A correct purchase could elevate a household’s moral tone; the wrong choice could exert a malevolent influence.

Phony luxury was especially dangerous: false marble mantelpieces and imitation-mahogany sideboards were pernicious because they were attempts to deceive. If you spend your life among such objects, you are in danger of being infected by their example: it is as “morally injurious to keep company with bad things, as it is to associate with bad people.” Morally elevating furniture often had ecclesiastical associations—hence the popularity of corner cupboards that looked like baptismal fonts, Gothic chair backs, stained-glass panels, and religious statues and mottoes.

Early Modernist architects such as Le Corbusier, de Botton remarks, had similar motives but different goals: they “wanted their houses to speak of the future, with its promise of speed and technology, democracy and science.” Some of them, however, produced buildings that looked simple and elegant but didn’t quite work: the flat roofs leaked in wet climates, the metal railings rusted. Occasionally this architecture also made people psychologically or physically uncomfortable. Anyone who has ever tried to descend a floating staircase without risers or an effective handrail, or sat through a dinner party in a chair designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, will recognize these sensations.

Today, just as in the past, de Botton claims, we call a building beautiful if it reflects our values:

The buildings we admire are ultimately those which, in a variety of ways, extol values we think worthwhile—which refer, that is, whether through their materials, shapes or colours, to such legendarily positive qualities as friendliness, kindness, subtlety, strength and intelligence.

Such buildings, he believes, can also have a positive effect on their inhabitants. The right house can cause feelings of humility, a desire for calm, and “an aspiration for gravity and kindness.”

One of de Botton’s most interesting assertions is that people have always found buildings beautiful not so much when they expressed current values as when they expressed “those values which the society in question was lacking.” He claims that

we are drawn to call something beautiful whenever we detect that it contains in a concentrated form those qualities in which we personally, or our societies more generally, are deficient.

This connection between art and personal lack runs through all of de Botton’s work. In The Art of Travel, he proposes that we seek abroad what is missing in our own lives, “what we hunger for in vain at home,” just as when we fall in love with someone from another country.

The fantastic exuberance of Baroque and Rococo, de Botton proposes, was a reaction to a world “where violence and disease were constant threats, even for the wealthy.” The gilded mirrors and barley-sugar columns, the whipped-cream cherubs and garlands of flowers and ribbons provided a refuge from the disorder and ugliness outside. By the late eighteenth century, however, advances in technology and trade had made life safer but also more complicated, and the growth of cities had isolated many from the natural world. As a result, there was “new enthusiasm for informal clothing, pastoral poetry, novels about ordinary people and unadorned architecture and interior decoration.”

Today, in de Botton’s view, “much of the developed world has become rule-bound and materially abundant, punctilious and routine” and we therefore again long for “the natural and unfussy, the rough and authentic.” This might account for the popularity, in cities like New York and London, of apartments with minimal (but always obviously expensive) furniture, and walls stripped down to raw brick or rough weathered planking. The more pressure and confusion and exhaustion a city dweller feels, the more likely she or he is to choose such a home. As de Botton says, “a whitewashed rational loft, which seems to us punishingly ordered, might be home to someone unusually oppressed by intimations of anarchy.” He describes his own attraction to Amsterdam, in which he sees “order, cleanliness, and light”—suggesting, though he does not say so, that he finds London chaotic, dirty, and dark.

One of de Botton’s most attractive qualities as a writer is his ability to manage his self-contradictions gracefully. Though he praises beautiful buildings for promoting happiness and virtue, he admits that they do not always make people happy or good, remarking how “John Ruskin acknowledged that few Venetians in fact seemed elevated by their city.” Buildings can also “be accused of failing to improve the characters of those who live in them,” since some of the most disagreeable tyrants of all times have dwelt in handsome palaces. For the average man or woman, however, de Botton suggests, the psychological and moral influence of architecture is strong. In London, when a violent rainstorm drove him to seek shelter in a McDonald’s on Victoria Street, he was gradually overcome by nervous despair:

The setting seemed to render all kinds of ideas absurd: that human beings might sometimes be generous to one another without hope of reward; that relationships can on occasion be sincere; that life may be worth enduring…. The restaurant’s true talent lay in the generation of anxiety. The harsh lighting, the intermittent sounds of frozen fries being sunk into vats of oil and the frenzied behaviour of the counter staff invited thoughts of the loneliness and meaninglessness of existence in a random and violent universe.3

As soon as the heavy rain abated, de Botton escaped from his artificially prolonged stay in McDonald’s into the silence and space of nearby Westminster Cathedral, where

everything serious in human nature seemed to be called to the surface…. The stonework threw into relief all that was compromised and dull, and kindled a yearning for one to live up to its perfections.

There “it seemed entirely probable… that an angel might at any moment choose to descend,” and ideas that would have sounded demented in McDonald’s “had succeeded…in acquiring supreme significance and majesty.”

The flip side of the benevolence and moral value of good design, for de Botton, is the pernicious and perhaps even malevolent effect of bad design. Ugly buildings, in his view, are the result of “a pedestrian combination of low ambition, ignorance, greed and accident.” Choosing to live in one, if you do not have to, expresses

the same tendency which…will lead us to marry the wrong people, choose inappropriate jobs and book unsuccessful holidays: the tendency not to understand who we are….

If we have the ability and/or good luck to live in a beautiful building, we may become happier and better. But the attachment to our home that we then develop, de Botton warns us (like all human attachments), is threatened by change and loss. Love of a domestic dwelling can involve constant grief at its need for upkeep and repair—a grief familiar to anyone who has returned to a beloved house after even a few months away. We may also fear to commit our affections to a beautiful church or school or office, just as we may fear to commit to a person, knowing that buildings, like people, may be destroyed by acts of God or man, and that they all eventually fall apart. In the end, however, de Botton is too much of an optimist, and also too much of an aesthete, to counsel us to give up the great happiness that architecture can sometimes bring.

This Issue

March 15, 2007

-

1

In fact, the hyena, which dwells exclusively in Africa, southern Asia, and international zoos, has what Wikipedia calls “a chirping, birdlike bark that resembles…hysterical human laughter” rather than the sounds generally associated with sexual passion.

↩ -

2

Quoted in Jerry Griswold, Feeling Like a Kid: Five Essential Themes in Children’s Literature (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006), p. 24.

↩ -

3

De Botton’s experience, while exaggerated, is not atypical. As is well known, McDonald’s restaurants are deliberately designed both to attract customers and to discourage them from lingering, in order to produce what is known in the trade as “maximum throughput.” The bright colors and the huge shiny photographs of high-calorie food draw people in; but the noisy acoustics, glaring overhead lights, small crowded tables, and uncomfortable seats encourage customers to leave as soon as they have finished what is appropriately called “fast food.”

↩