1.

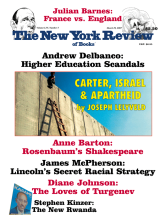

Perhaps an intrepid researcher will one day go through the many Internet pages that make assertions pro and con on the question of whether Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian territories can properly be assessed as “apartheid.” Then we may be in a position to tell whether the first polemicist to sling the term in the context of the West Bank was a foreigner, a Palestinian, or, just possibly, an Israeli. Suffice it to say, it wasn’t Jimmy Carter, whose recent book, with its unpunctuated title Palestine Peace Not Apartheid, has been high on the best-seller lists for nearly three months despite—maybe, in part, because of—the wrath his use of the term has provoked among Israel’s supporters. Not all of them have been as restrained as Abe Foxman, the director of the Anti-Defamation League, who complains of Carter’s “bias” but avoids tossing the epithet “anti-Semite” at the president who, nearly three decades ago, brokered the Camp David accord, which did more to secure Israel’s place and legitimacy in the region than all the diplomacy that preceded or followed it.

The branding of Israel as an “apartheid state” was one of the themes of resolutions presented at the World Conference Against Racism held in Durban, South Africa, under United Nations auspices in 2001 (and one of the reasons Secretary of State Colin Powell cited for calling the American delegation home). Yet at about the same time, the term “apartheid” began to surface in discussions in what might broadly be called the Israeli peace camp as a plausible if somewhat contentious way of characterizing the occupation of the territories or the prospects of the Jewish settlements there; as a benchmark, a description of what the occupation already was or might become. Five years ago, writing in Haaretz, Israel’s most respected newspaper, Michael Ben Yair used the A-word in describing the occupation that he said began on “the seventh day” of the Six-Day War. Ben Yair, the attorney general in the governments of Yitzak Rabin and Shimon Peres in the 1990s, is no fringe figure. “Passionately desiring to keep the occupied territories,” he wrote,

we developed two judicial systems: one—progressive, liberal—in Israel; and the other—cruel, injurious—in the occupied territories. In effect, we established an apartheid regime in the occupied territories immediately following their capture.

Two years later, the political commentator and former deputy mayor of Jerusalem Meron Benvenisti used the word prospectively. Ariel Sharon’s plan to disengage from Gaza and build a security wall along—and beyond—the western frontier of the West Bank was tantamount, he argued, to making Israel “a binational state based on apartheid.” It meant, he said, “the imprisonment of some 3 million Palestinians in bantustans.”

In recent weeks, largely in response to the controversy in this country over the Carter book, the word “apartheid” has popped up in Israel’s interminable security discussion more often there than it normally does in print. Thus we find Uri Avnery, a veteran of the peace movement, detecting “a strong odor of apartheid” in a military order (since rescinded) forbidding Israeli drivers to give rides to Palestinians on the West Bank; and Shulamit Aloni, the education minister in the last Rabin cabinet, declaring on the Web site of the tabloid Yediot Ahronot that Israel “practices its own, quite violent, form of apartheid with the native Palestinian population.”1 Two clicks on the Web site of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions, a small but vocal peace group, brings you to a screen headed “Campaign Against Apartheid,” proposing a “Civil Society Call to Action.” Israelis using the term “apartheid” in debates that go on mainly in Hebrew provoke a predictably hostile reaction. But that reaction in Israel is ritualized by now, not nearly as fresh in its outrage as the one the former president aroused here by using “apartheid” as a verbal battering ram in order to reopen a debate about the occupation of Palestinian lands—one that Democrats and Republicans, unlike Israelis, outdo each other in shunning.

Two uses of “apartheid” are in play when attempts are made to attach the word to Israel: the Durban usage, citing Israel as an “apartheid state”; and, more commonly, the application of the term to the occupation in the territories, which has now gone on for all but nineteen of the nearly fifty-nine years of Israel’s existence, through different phases as Jewish settlements took root and expanded on the West Bank along with the heavy military presence that guards them, supplemented now by a network of roads for the exclusive use of the settlers and the Israel Defense Forces. The settlements, roads, barriers and military presence have effectively divided the West Bank into security zones or enclaves, severely limiting Palestinian passage from one zone to the next. The crushing impact on Palestinian lives and families is clear enough. The debate on whether it amounts to “apartheid” turns on whether it’s to be seen as a legitimate and reversible response to the threat of terrorism across the border in Israel, or whether it’s meant to be as permanent as it looks.

Advertisement

The Durban usage, labeling Israel an “apartheid state,” is relatively easy to dismiss as propaganda. Apartheid, as developed by Afrikaner nationalists in South Africa, was both a doctrine and a huge legal apparatus. It was based on a system of racial classification and elaborated in scores of laws and hundreds of regulations that stripped the black majority of virtually all rights, including the right to enter and remain in “white areas,” deemed to be most of the land. Nothing remotely resembling the apartheid doctrine or apparatus can be found within Israel itself. It’s indisputable that Arab citizens face discrimination of various sorts but on paper at least, they have the same rights as Jewish citizens (except for what might be called an existential fact, recently underscored by a group of Arab intellectuals and activists, that the 1.3 million Arabs of Israel live in a state that implicitly relegates them to second-class status by defining itself as Jewish).2

Still, to equate Israel with white South Africa of the apartheid era amounts to saying the Jewish state has no legitimacy at all, that the 1948 partition establishing it needs to be undone in order to accommodate all Palestinians who might want to regain residence there. In essence, it’s to say what the absolutists in Hamas say in making their all-or-nothing demands: that the only real Palestine is the territory that existed before partition (just as the dwindling number of Jewish absolutists argue that the only real Israel is Greater Israel).

It’s only when one speaks of the lesser “Palestine”—meaning, as Jimmy Carter says he does, the territories that would participate in the full-fledged two-state solution that’s supposed to be the aim of Western diplomacy—that “apartheid” begins to shape up as a charge more troubling than an epithet, as a loose analogy that carries some weight. That’s how Carter defends his use of the term. He says his title—which can be read either as an accusation or a plea—refers only to the occupied territories, not democratic Israel. What’s remarkable is how little he has to say about the analogy he sees between the bygone white regime in South Africa and the occupation of the West Bank as it still exists (and as it existed in Gaza before the withdrawal of the settlements in 2005).3 Despite the explosive force of his use of the word in his title, Carter alludes to apartheid only glancingly in his text, touching on the subject in just four paragraphs in the entire book, adding up to barely a couple of pages. The case is so self-evident, he seems to feel, that it needn’t be made. The one qualification he offers is itself off the mark. “The driving purpose for the forced separation of the two peoples is unlike that in South Africa—not racism,” the former president writes, “but the acquisition of land.”

Obviously, apartheid had plenty to do with racism but land was also at the heart of the South African struggle. This was the case even before the word “apartheid” gained currency at the time of the victory of the National Party in the 1948 elections, which ushered in an era of rule by Afrikaner nationalists that was to last for nearly half a century. (A coinage, “apartheid” meant more than separation; “separatehood,” with the same suffix as “brotherhood,” would be a possible translation if there were such a concept or word in English.) Apartheid rapidly evolved from a slogan into an ideology, one that had more ambitious goals than crude old-style segregation or supremacy. Basically it offered a promise that white South Africa could endure as a sovereign political entity for all time under Afrikaner leadership without sacrificing Christian values. That opened the door to a slew of oppressive laws and experiments in social engineering. Under the Group Areas Act, for instance, more than two million blacks and other nonwhites were forcibly moved from what were sometimes called “black spots” in areas designated as “white” to remote settlements and tribal reserves that were rebranded as “homelands.” In the process, their lands and homes were confiscated. Finally the denizens of the homelands were told they were citizens of sovereign states, that they were no longer South Africans.4 All this was in service of apartheid’s grand design.

With adjustments for the large differences in population size and land mass, it might be argued that land confiscation on the West Bank approaches the scale of these apartheid-era expropriations in South Africa. Jimmy Carter is well aware of the pattern of land confiscation there; he quotes Meron Benvenisti at length on the subject. But since he thinks apartheid in South Africa was all about race and not about land, he fails to see that it’s precisely in their systematic and stealthy grabbing of Arab land that the Israeli authorities and settlers most closely emulate the South African ancien régime. What could have been his most incisive argument in support of his provoking use of the A-word turns up in the pages of his book as little more than an aside.

Advertisement

There are other similarities of which Carter seems to be unaware. For instance, one of the features of apartheid in its last years as constant bureaucratic tinkering rendered the model steadily more complicated was its tendency to spin off various levels of legal status for black South Africans who were otherwise indistinguishable: some had permission (falling short of an inalienable right) to live as well as work in urban areas designated as “white”; others, called “commuters,” could work in these areas but not reside in them; still others could work and live there in single-sex hostels but not bring their families; a large residue had no permits to enter the so-called “white” areas (which were, in fact, nearly always majority black).

On the West Bank, as the hilltop settlements expanded from encampments around a few trailers into fortified suburban developments and the security situation grew more dangerous pretty much as a direct result, permits of various sorts, issued by the military authorities, have come in broadly analogous ways to govern movement by Palestinians. The latest set of permits are for some 40,000 Palestinians whose villages or fields have been cut off by the so-called “separation wall,” now about two-thirds built, that has helped to reduce the infiltration of would-be suicide bombers into Israel. (A self-proclaimed ban by Hamas on bombings inside the 1967 borders may have helped as much or even more.) Palestinians now stranded by the actual or projected wall in what are designated as special military regions between it and Israel’s de facto border have an unwelcome status all their own: they have no right of entry to Israel but need permits to visit the West Bank and permits to return to their homes.

Sometimes the wall is derided by domestic and foreign critics as “the apartheid wall,” though no such barrier was ever erected in South Africa. Similarly, there was never a South African parallel for the highways built on the West Bank exclusively for Jewish settlers, from which Palestinians have been barred, though these are sometimes also described as an apartheid feature. Carter doesn’t deal much with specifics but perhaps it is to such features as the wall and segregated highways that he’s alluding when he asserts, as he has in articles and interviews since publication of his book, that the situation on the West Bank is in some ways “more oppressive” for Palestinians than apartheid was for South Africa’s blacks.5

Or he may be talking economics: Israel has proven that it’s not at all dependent on imported cheap labor from the territories, that it can get along just fine with Thais, Filipinos, and Romanians. It has thus gone beyond South Africa’s apartheid theorists who dreamed of a day when they could do without black labor but never got close; on the contrary, their economy became steadily more dependent on black skilled workers who ultimately couldn’t be denied limited trade union and residence rights, undermining the theoretical model of strict separation. Or, again, Carter may be thinking about the security forces: there’s a much bigger and more obvious military presence in the occupied territories than normally existed in the black townships and “homelands” of the apartheid state; and, not just proportionally but in absolute numbers, Israel holds many more supporters of Palestinian movements as prisoners than South Africa ever detained in its continuing crackdown on mainly black anti-apartheid movements. All of these are things Carter might have meant, might have said, but he leaves it to readers to fill in the blanks in his argument.

What’s reminiscent in Israel of apartheid in its later, most cynical and fully developed phase is less the separation than the complexity—all the arbitrary rule-making by a dominant authority intent on retaining its dominance, an authority that’s fundamentally and obdurately unresponsive to the needs of most residents of the territories because it sees its mission as safeguarding a minority it has subsidized and favored from the start. In the case at hand, that of the West Bank, this means the Jewish settlers whose numbers have steadily grown over the decades since Jimmy Carter as governor of Georgia, on his first trip in 1973—to what’s for him, first and foremost, “the Holy Land”—immersed himself in the Jordan River near the point where he calculated, on the basis of his own reading of the Gospels, that Jesus Christ had been baptized.

Carter, seeming to view apartheid through a Dixie prism, defines it essentially as segregation; “forced separation,” he calls it, as if the purpose of force is to pry apart people who might end up living together. But on the West Bank separation is not the issue; few settlers are disposed to live at close quarters with Arabs and few Palestinians care to have the settlers in their midst.6 The basic issue is one of control, which was the point of the settlements in the first place, for both the military strategists and the ideologues who backed the movement. And now that they have spread out so widely across the West Bank, the issue of control includes the question of whether a two-state solution can still make room for a Palestinian state that will have any sovereignty worthy of the name. The settlements have long since become the “facts on the ground” they were always meant to be and, therefore, the main obstacle to the “peace” Carter ardently hopes to see.

Those who have taken issue with his book generally skirt what he has had to say about the settlements. But they represent the nub not only of his argument but of the problem. Sensing a coldness toward Israel—or at least its security establishment, struggling on a day-to-day basis to prevent bombings—his critics catch him out on errors that might otherwise have been overlooked and pose the question of why he can’t be as indignant about suicide bombers as he is about the occupation. The complaint has more to do with matters of emphasis and tone than the points he actually makes. Carter condemns the dispatching of suicide bombers into crowds of Jewish civilians but does so coolly, tersely, almost clinically, stressing that such attacks are counterproductive, without conveying the kind of visceral horror that the phenomenon arouses among Israel’s supporters and many others as well.

He’s capable of such feelings when he turns to the settlements. Carter’s now standard response to his critics is to say that the “horrible oppression” of Palestinians is really the root of the problem, that most Americans and even many Israelis are ignorant of this because they haven’t seen what he has seen: the massive apartment complexes that have been basically absorbed into Jerusalem on land that once was Arab; the hilltop settlements beyond the capital with their California-style condos, small shopping centers, and separate highways, strategically perched above Palestinian towns and villages that are encircled and frequently isolated from each other by military patrols and checkpoints.7 He’s only half right when he suggests as he has in recent interviews that the American press has consistently failed to portray this picture. (If it’s too often taken for granted now, that’s because correspondents and editors have come to consider it an old story, having handled it so many times in the past; also because the proliferation of military checkpoints frequently makes movement on West Bank roads almost as difficult for correspondents as it is for Arab residents.)

But Carter is considerably more than half-right in arguing—and, yes, even crying from the rooftops—that the status quo is unsustainable and not amenable to a unilateral settlement imposed by Israel; right too when he argues that our discussion of issues centering on a “peace process” that is all process and no peace has become conspicuously one-sided. Carter blames “a submissive White House and US Congress during recent years” and “powerful political, economic, and religious forces in the United States.” He doesn’t resort to the term “Jewish lobby” and has recently made it clear—not in his book but in a “Letter to Jewish Citizens of America” that he wrote in December in response to the furor—that he intended to include conservative Christians in his chiding. In his own words:

The overwhelming bias for Israel comes from among Christians like me who have been taught to honor and protect God’s chosen people from among whom came our own savior, Jesus Christ.

Whatever the cause of the one-sidedness he deplores, it’s necessary only to recall the resolutions both houses of Congress rushed to pass last summer in support of Israel’s retaliatory offensive against Hezbollah in order to gauge whether he’s making a reasonable point. The offensive—which devastated Lebanon, killed hundreds of civilians, and ultimately did more to undermine the new government of Prime Minister Ehud Olmert than it did to weaken Hezbollah—won the backing of the House of Representatives by a vote of 410–8. When Carter’s book was about to appear, Representative Nancy Pelosi, soon to become speaker, was quick to say he didn’t speak for Democrats on these matters; obviously, she was right.

So let’s grant that Carter has now stimulated potentially useful debate (more, surely, than the Iraq Study Group’s call for a new effort on the Israel– Palestinian impasse, which seemed to fade from public discussion within a couple of news cycles after former Secretary of State James Baker stressed its urgency the day the report came out). And let’s grant that the former president’s peculiar combination of rectitude and starchy pride can be a little irritating, as it was three decades ago when he lectured us on energy independence and then blamed our “malaise” for our failure to heed him. Questions can still be asked: Is “apartheid,” like “malaise,” a word he could have done without? And, with or without it, how much merit does his slender book have as a guide to the conflict?

Carter defends the use of “apartheid” in his title like a politician defending a particularly tough attack ad. He says he doesn’t regret it, that it was a deliberate provocation that has had its intended effect; in other words, that it works as an attention grabber. In his hands, it’s basically a slogan, not reasoned argument, and the best that can be said for it, as we’ve seen, is that significant similarities can be found in the occupation of the territories. It’s understandable if Israelis who feel sickened by a sense that they’re personally implicated in the brutality of the occupation resort to the word in order to shame their countrymen. Some outsiders might contemplate the phenomenon of suicide bombing and ask how they would deal with the bombers before resorting to the label “apartheid.” Others might insist on their right to be outraged about both the bombings and the oppressive measures imposed in the name of counterterrorism.

Meron Benvenisti, who has been intrigued by the comparison to South Africa over the years, now calls for a rhetorical cease-fire. The use of the term “apartheid,” he wrote back in 2005, has become in Israel a “mark of leftist radicalism,” while its denial stands as proof of “Zionist patriotism.” Objective comparison or discussion of the validity of any comparison is “nearly impossible.” Anyone who goes into the question, Benvenisti wrote, “will be judged by his conclusions.” The choice, he said, is between being called an anti-Semite or a fascist. The occupation should be seen in its own harsh light, he concluded, rather than subjected to a comparison.

Maybe so. Still, there remains one hopeful thread that can be plucked from the tangled web of meaning the word “apartheid” came to have in South Africa: the design didn’t work; the system finally ran its course because its supporters in the Afrikaner establishment lost faith in their ability to sustain it. Apartheid was then disowned by the party that created it. Whatever the motives for Ariel Sharon’s decision in 2005 to pull the settlements out of Gaza, it was interpreted by many as a sign that a similar erosion of faith was already far advanced in Israel. The dilemma now is not whether to trade land for peace but whether that’s now even possible.

Which brings us to the real point of Jimmy Carter’s actual book, which is more memoir than tract and more tract (as it’s probably only fair to expect of an eighty-two-year-old former head of state) than a serious excursion into the conflict or a sympathetic consideration of the passions that fuel it. Carter surely has a right to his pride; the Camp David accord remains the biggest stride to acceptance in the region that Israel has taken. And, no doubt, he is impressive for his commitment, his eagerness to continue to travel the area even into his ninth decade, a not-always-welcome but hard-to-resist global do-gooder.

Still, a loosely stitched narrative of his occasional meetings with various presidents, prime ministers, and kings since leaving office and of the elections he has monitored—interspersed with commentary on the ways his successors tried to advance the cause of peace or, mostly, failed to do so—makes for something less than a full-bodied account of the conflict. Jimmy Carter puts himself front and center, using the first-person pronoun, at the start of eight of his first fifteen chapters; even more telling is the flash of anger he shows when he’s told by the White House of George W. Bush that it doesn’t want him dropping in on Syria’s Bashar al-Assad. “I tried to explain,” he huffs, “that I had known Bashar since he was a university student and that I would be glad to use my influence to resolve any outstanding problems, as I had done with his father.” But it’s no go.

Carter is not eager to sit in judgment on any leader who receives him cordially—Hafez al-Assad (father of Bashar), Arafat, and Sharon are all treated evenhandedly, as fellow members of the fraternity of world leaders. In part, that’s because he usually has some point he wants to make in the cause of peace as he construes it; it’s also because the man’s ego is full of vigor.

So Carter’s implicit answer to whether a land-for-peace deal is still possible is that it would have happened already had his successors had his kind of commitment and grasp of the essential problem. Stripped of its self-referential passages, the real point of the book is that peace doesn’t have a chance without an active commitment by the United States that includes a readiness to lean on Israel. He praises Bill Clinton for his “strong and sustained efforts to find some reasonable accommodation,” then complains bitterly that in the Clinton years “there was a 90 per cent growth in the number of settlers in the occupied territories,” most of whom would have remained on the West Bank under the terms that Clinton blamed Arafat for rejecting at Camp David in the summer of 2000. Carter is more inclined to lay the blame on Israel’s then prime minister, Ehud Barak, whose offer he characterizes as having been less generous in reality than was said at the time.8 “There was no possibility,” he writes, “that any Palestinian leader could accept such terms and survive.” If political survival of the leader is the standard, he might also have acknowledged that Barak—particularly in his acceptance of Clinton’s modified terms in December—probably went as far as any Israeli leader who hoped to survive could have gone. (Having failed, he was then exiled to the political wilderness by Israeli voters and members of his own battered Labor Party.)

The old peacemaker manages to forget that politics shaped diplomacy even in the Carter years when a United Nations ambassador, Andrew Young, could be fired for having unauthorized contacts with the Palestine Liberation Organization. The Jewish settlements on the West Bank offend him as an encroachment on Palestinian rights but also on a personal basis, for he believes Menachem Begin made a verbal pledge to him to freeze them, then reneged on it. That’s now debatable, for as he ruefully acknowledges, he failed to get it in writing. If Carter is right, he doesn’t go on to explain why he seemingly avoided a showdown when he might have done something as president about Begin’s stalling; perhaps he was saving that confrontation for his second term.

Now justly outraged over “the almost unprecedented six-year absence of any real effort” to bring about a negotiated settlement, in his final pages he puts the onus for a solution wholly on Israel while contemplating the blatant lack of balance in American policy. “The bottom line is this: Peace will come to Israel and the Middle East,” he writes, “only when the Israeli government is willing to comply with international law.” The solution he foresees mixes the call in Resolution 242, now nearly four decades old, for an Israeli withdrawal from the territories; the Arab League plan of 2002, offering Israel normal relations and a “comprehensive peace” once a sovereign Palestine with its capital in East Jerusalem has been created in the territories and a “just solution” for the refugee problem has been achieved; and, lastly, the Geneva Initiative of a year later, an unofficial exercise by respected out-of-power Israelis and Palestinians seeking to define such a peace (resulting in a plan that included specified land swaps to allow the Jewish settlements closest to Jerusalem to be absorbed into Israel).

Officially, something very much like this is still the goal of American policy; in practice, the present administration, embracing Israel as an ally in its “Global War on Terror,” has all but abandoned the role of broker. It has never gone beyond lip service to the sort of sustained diplomatic effort for which Carter calls (along with poor Tony Blair, who tried and failed to claim it in exchange for his support for the Iraq war, and the leaders of most other governments we’re in the habit of describing as allies).

2.

Anyone needing a refresher course on how far from simple such a resolution would be should take a long, close look at Jeffrey Goldberg’s conflicted, deeply sad account of his own pilgrim’s progress: from starry-eyed Zionist pioneer brought up in Malverne, Long Island, determined “to live as a free Jew in the Promised Land,” to disillusioned military policeman, to open-hearted reporter learning to see the struggle from more than one side while traveling with two passports, one American and one Israeli.

Goldberg, now the Washington correspondent of The New Yorker, gets to a level of experience that’s invisible from the heights traveled by statesmen who move about in entourages on well-prepared itineraries designed to make any contact with reality a symbolic event. He has seen Israeli soldiers brutally beat Palestinian prisoners; has witnessed the shooting of a young rock thrower on the West Bank; has himself sprayed tear gas at prisoners behind a barbed wire fence; has heard bereaved Sephardic Jews scream “Death to Arabs!” at the scene of a suicide bombing; has had a close call himself at a Hamas rally and been arrested in Gaza, then witnessed a ceremony there for the induction of young “human bombs”; has tried and failed to understand a well-educated Palestinian mother who says she wants martyrdom for her son (“a sane woman who saw her womb as a bomb factory).”

This is not a sentimental education. Yet Goldberg struggles with his emotions at every turn, holding on to his love for Israel even as he discovers that he can’t transform himself into an Israeli. A tip-off comes when an attempt is made to recruit him for the security service: he’s told it would never give its highest clearance to anyone born in America. But that’s not the essence of his problem. It’s that the example of strength and virility he thought Israel offered soft Diaspora Jews like himself also yields “Jews devoid of pity.”

His comrades in the Israeli army suspect him of being what they call a yafei nefesh, “a beautiful soul,” meaning a bleeding heart. “You can’t beat them enough,” one says, by way of telling him he doesn’t understand the mentality of Arabs. “It’s true, of course, that I didn’t understand the mentality of Arabs,” he later reflects. “But the realization was dawning on me that it was also the Israelis, the flesh of my flesh, that I did not understand.”

To find an anchor for his turbulent feelings and for his narrative as well, Goldberg concentrates on his relationship with a single Palestinian named Rafiq Hijazi whom he encounters under inauspicious circumstances: Goldberg is a prison guard at Ketziot, Israel’s biggest prison camp, spread across a bleak landscape where the Negev and Sinai deserts meet; Rafiq, a prisoner with loyalties to Fatah or Hamas.9 They chat through a fence and the beautiful soul from Long Island, sensing that they’re alike in some ways, asks himself whether it’s possible that they could be friends, and if so, whether their friendship could prove in microcosm to be a test case of the ability of Jews and Arabs to coexist in genuine peace.

Their story is subject to mood swings, in prison and later, ups and downs influenced on both sides by the course of the larger struggle. There are interruptions and distractions; for eight years after Goldberg leaves Ketziot they have no contact and then, once they’re back in touch, Goldberg flies off on reporting assignments that he now feels a need to cram into his narrative because they’re too good to leave out, rather than because they advance the story he has set out to tell. Still, as we encounter Rafiq and his extended family in Gaza, Washington, D.C., and finally Abu Dhabi, his story comes through.

He was a Fatah member after all, a much more important operative within the prison camp than the Israeli security service was ever able to detect. In fact, as he later reveals, he was the keeper of “The List”—that is, the list of Palestinian collaborators who have to be interrogated mercilessly and eventually eliminated. Goldberg is stunned but pursues the relationship, which he sometimes doesn’t trust. In part, it seems obvious, he does so because he sees the possibility of writing about it; in part because it makes a real claim on his mind and heart. Rafiq also turns out to be a professor of statistics and an orthodox Muslim with a wife who stays covered. He believes in the literal truth of the Koran, doubts there was ever a Jewish temple in Jerusalem where the al-Aqsa mosque now stands. Yet somehow this Jew and this Muslim end up trusting each other, sharing the hope that their friendship can endure, that it has meaning. “I don’t want you to die. I want you to live,” the Fatah man tells his former guard.

Of these two books, there’s no question about which one is deeper, truer. But it’s only the thinner, weaker one, by the old political actor taking one of his last bows, that presumes to answer the question of what’s to be done. Above all, it’s a political statement, a political act. In a tough review of Carter’s book in The Washington Post, Jeffrey Goldberg takes no real issue with the former president on the central issue of the Jewish settlements. “Many Palestinians, and many Israelis, have died on the altar of settlement,” he writes. For him this is “a tragedy, of course.” If Carter in his use of “apartheid” is too judgmental in the view of his critics, maybe “tragedy” is not judgmental enough, seeming to suggest, as it does, that the settlements were not the result of deliberate and stealthy planning but simply good intentions gone wrong.

As a journalist, Goldberg doesn’t take it on himself to answer Carter’s challenge. He seems inclined to think the answer has to come from the Palestinians. Twice in his book he wonders aloud about why they haven’t faced the occupation with the Gandhian tactic of nonviolent resistance. Gandhians have hardly been conspicuous in the Israeli leadership, but on the level of tactics it’s a good question; nonviolence could hardly have accomplished less for the Palestinians than suicide bombing. It’s also a reminder of the downward spiral that sets in when two sides come to recognize only the other’s darkest impulses, each saying that the other understands only one language, the language of violence. That’s what South Africans, black and white, used to say of each other; it’s what many Israelis and Palestinians have told themselves for years.

Jimmy Carter says the Americans have to intervene. Jeffrey Goldberg wants the Palestinians to renounce violence. Maybe that means that if anything positive is going to happen, it’s up to the Israelis to make the next move, if only to demonstrate that they’re not permanently trapped in their old security doctrines and failed dreams of dominance (or those of a waning administration in Washington). Anwar Sadat and Yitzak Rabin, each in his own time, showed that the situation can be changed by an imaginative leap; each then paid with his life. Now each side says there’s no negotiating partner; and each side has proven to be right, so far.

This Issue

March 29, 2007

-

1

Ms. Aloni’s article appeared in translation on Salon.com.

↩ -

2

For an effective answer to the charge that Israel is an “apartheid state,” see “Apartheid? Israel Is a Democracy in Which Arabs Vote,” an article by Benjamin Pogrund, a crusading anti-apartheid journalist from South Africa who now lives in Jerusalem, where he is involved in efforts aimed at recon-ciliation between religious Jews and Muslims. The article first appeared in Focus, a publication of the Helen Suzman Foundation in Johannesburg and now available on the foundation’s Web site. Pogrund also decries the application of the term to the occupation on the West Bank, calling it “a lazy label.” See The New York Times, February 8, 2007, for a dispatch on “The Future Vision of Palestinian Arabs in Israel,” the statement by Arab intellectuals and activists.

↩ -

3

Israel maintains that its occupation of Gaza ended with its unilateral withdrawal of troops and settlements, though it makes frequent military incursions in response to rocket attacks from the territory. Human Rights Watch argues that Israel “continues to have obligations as an occupying power in Gaza because of its almost complete control over Gaza’s borders, sea and air space, tax revenue, utilities, and the internal economy of Gaza.”

↩ -

4

This aspect of what was called “grand apartheid” is echoed in the plan of Avigdor Lieberman, now a deputy prime minister, to forcibly “transfer” Arab citizens of Israel to Palestinian jurisdiction unless they pass a loyalty test.

↩ -

5

For example, see Jimmy Carter, “Speaking Frankly about Israel and Palestine,” Los Angeles Times, December 8, 2006.

↩ -

6

“The desire for national self-definition and separation dominates the Israeli– Palestinian conflict,” Meron Benvenisti wrote in Haaretz, May 19, 2005.

↩ -

7

Interview on National Public Radio, January 25, 2007.

↩ -

8

Carter is not the only one to have reached this conclusion. See Hussein Agha and Robert Malley, “Camp David: The Tragedy of Errors,” The New York Review, August 9, 2001, and responses from critics, including Dennis Ross (September 20, 2001) and Ehud Barak (June 27, 2002).

↩ -

9

The Ketziot prison was shut down following the prisoner releases that accompanied the Oslo agreement. It was reopened in 2002 as the second intifada raged.

↩