In response to:

'Words, Words, Words' from the March 29, 2007 issue

To the Editors:

I am grateful to Anne Barton for some textual corrections in my book The Shakespeare Wars and for finding “virtue” in its “sheer energy” and”assiduity,” and for conceding it has been “much praised” and “widely read” [NYR, March 29].

But I must say I am stunned by the utter misrepresentation of my position in a central controversy I treat in the book: her claim that I manifest an “insistence throughout upon the single, inviolable nature of Shakespeare’s text, as he originally wrote it,” and that I am “unable to countenance the idea of a Shakespeare changing his mind about a play over time,” further that I have “no patience with ‘revision theory,’ with the Shakespeare who felt impelled to revise his own work….”

These statements are, alas, just plain false: I neither believe what is ascribed to me, nor, as anyone who reads the book will discover, do I endorse them. I am at a loss how she could write this since as she acknowledges I argue the opposite in a New Yorker story (May 13, 2002), and have not changed my view that the controversy over revision is a valuable one and attention should be paid to the arguments of the “revisionists” even if specific instances of revision cannot be proven beyond doubt to be Shakespeare’s.

This is not at all the same as saying I believe in an inviolable “Lost Archetype” and I devote seventy-five pages of the book to assessing both the strengths and weaknesses of dozens of individual potential revisions and the shifting tides of scholarly opinion on the question over the past quarter-century.

This is something that can be verified by any reader who gets as far as Chapter 2 whose final (epilogue) sentence includes this statement: “…we cannot after all this time, decide what the true identity of the text of Hamlet is or how it came to be….” Hardly an argument for “inviolability”!

Nothing could contradict more clearly Ms. Barton’s misrepresentation about my supposed belief in a “Lost Archetype.” Unless, the line on page 79, in which, in concluding a chapter praising the work of Ann Thompson, co-editor of the new Arden three-text Hamlet, I single out her position that “a century of bibliographic scholarship had corroded the foundation, the rationale for trying to confect a single Lost Archetype of Hamlet from the found objects of the three imperfect Hamlet texts we have.” Hardly an argument for a “Lost Archetype”—quite the opposite.

Just a couple more examples of how completely wrongheaded Professor Barton’s characterization is. On page 90 I suggest the revisions make it “possible to imagine one is seeing [Shakespeare] rehearsing alternative phrases in the theater of his mind.” And on page 100 I praise Ann Thompson’s “agnostic” position against the “drive by past editors to establish a final, definitive text” of Hamlet. Professor Barton utterly misleads readers of her review of my book about this basic question.

A scholar such as Ms. Barton should be able to recognize that some arguments do not lose their validity because they may not in every instance be definitively resolved.

Other among her more obvious errors: Professor Barton asserts I do not pay attention to the work of Lukas Erne, when anyone who gets to page 35 can find a sympathetic summary of his argument (one of four references easily found in the index).

She is again inaccurate in stating that I believe filmed Shakespeare is always superior to staged Shakespeare. Rather I point out that there are films featuring great Shakespearean actors, many now dead, that I regard as superior to the average stage productions one is likely to see featuring talented but lesser actors in one’s lifetime. Indeed I include a subhead “When Shakespeare on Film Goes Wrong.” Again an argument in which I am careful to present pros and cons but, as with her delusion of a preference for an “inviolable” Lost Archetype, one in which she reduces my position to an uncritical preference for one side or another. As Professor John Sutherland pointed out in his review of my book for the Financial Times I refuse to take sides in many of these “wars,” this one especially.

Why should a critic I’d always thought astute make such glaring errors? Particularly about the “revisionist” question which I am careful to consider without declaring one side a “winner” as she seems to imply or want. Perhaps she was blinded by my critique of a revisionist scholar she’s praised, James Shapiro [Barton, “The One and Only,” NYR, May 11, 2006], whose heavy-handed use of the revisionist case (he argues as if he could read Shakespeare’s mind, to tell us, without evidence, that Shakespeare himself cut the final thirty-five-line soliloquy in the 1604 Quarto of Hamlet to make the play more fast-paced), however foolish it may be, does not discredit the revisionist position, when articulated by more subtle scholars to my mind.

Or perhaps there is something closer to home, less than fully disclosed, to explain the evident animus and egregious errors in the review of my book (an animus not shared by equally distinguished critics such as John Gross and John Sutherland): Ms. Barton mentions, in her discussion of my views of Shylock, that someone named John Barton published a dialogue about Shylock between two actors in one of his books. Not all readers of her review will be aware this is her husband John Barton. I devote an entire chapter to Sir Peter Hall, a co-founder with the talented Mr. Barton of the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Sir Peter’s theory of “iambic fundamentalism” which for a time at least involved Ms. Barton’s husband in a controversy with Hall over the best way to speak Shakespearean verse. I admire her loyalty but her readers deserve more transparency.

She complains about the length of my book and had I world enough and time I’m sure I would have found room for more discussion of Professor Barton and her husband’s undoubted achievements. But her distortion of my account of Shakespeare’s texts as displaying a preference for “inviolable” texts is intellectually inexcusable for whatever reason.

Her review certainly calls into question her assertion that “the Shakespeare wars” are not as contentious as my title suggests.

Ron Rosenbaum

New York City

Anne Barton replies:

Mr. Rosenbaum’s long letter requires only a brief reply.

First: I did not, as he claims, represent him as saying that “filmed Shakespeare is always superior to staged.” I reported his view that filmed Shakespeare—especially old Laurence Olivier, Orson Welles, and Peter Brook films—presented more of the “quintessential” Shakespeare than any staged production his readers are likely to see in their lifetime. That is the opinion he reiterates throughout Chapter 10 of The Shakespeare Wars.

Second: I fail to comprehend how the fact that I am married to John Barton is in any way relevant to the interchange I mention between the actors David Suchet and Patrick Stewart about the character of Shylock, as recorded in Playing Shakespeare.

Finally: It is difficult to reconcile Mr. Rosenbaum’s insistence now that he takes “revision theory” seriously—the idea of a Shakespeare who returned to and reworked some of his plays after initial publication and performance—with his Chapter 4, with what he calls “the scandal of Lear’s last words.” There, he maintains that the discrepancy between the quarto and folio texts constitutes “the most important, difficult, complex, embarrassing, humbling, scandalous, unresolved question in Shakespeare studies.” Which one, he finds crucial, is the more “Shakespearean”? One might as profitably ask the same thing of The Tempest, a late play, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, a relatively early one. Instead of referring to the “apparent unsolvability” of a choice between the quarto and the folio texts—and claiming that it is a “damaging… breach” in “literary culture”—why not accept the two versions of Lear’s last words, and the final scene more generally, as independent and equally valid alternatives?

I stand by everything I wrote in my review of The Shakespeare Wars.

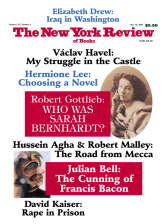

This Issue

May 10, 2007