Recently, the Polish government attempted to strip Bronisław Geremek of his seat in the European Parliament, to which he had been elected in 2004. The Parliament immediately voted to condemn the Polish government’s action. One of Poland’s most distinguished public figures, Geremek was a leader of Solidarity and a former political prisoner of the Communist regime. As foreign minister from 1997 to 2000, he was responsible for Poland’s accession to NATO. The Polish government tried to have him dismissed because Geremek had refused to sign a declaration that he had not been a secret police agent during the Communist years.

The duty to make such a declaration was mandated by a new law of “lustration,” or purification, which was pushed through the Polish parliament by Poland’s right-wing government, led by President Lech Kaczyński and his twin brother, Prime Minister Jarosław Kaczyński, in a sweeping campaign to “purge” Poland’s professional classes of people who are suspected of having been secret collaborators of the security services between 1944 and 1990. The law, which took effect on March 15, required all Poles occupying professional jobs in the private, public, and state sectors and born before August 1972—including politicians, professors, lawyers, judges, journalists, bank managers, and the heads of schools, companies, etc.—to declare in writing within two months whether or not they had collaborated with the former Communist security services. Those who, like Geremek, refuse, or who give false information, could be banned from practicing their professions or holding public office for ten years.

EU parliamentarians called the Polish government’s actions against Geremek a witch-hunt. In refusing to comply, Geremek—whose Communist-era activities had already been vetted by previous governments and whose anti-Communist credentials are beyond dispute—declared the new lustration law a threat to civil liberties. In response, Prime Minister Jarosław Kaczyński accused Geremek of “damaging his fatherland” and “provoking an anti-Polish affair.” The same phrases were used by the leaders of Communist Poland years earlier when Geremek criticized their misrule.

On May 11, Poland’s Constitutional Court ruled that many of the new lustration procedures were unconstitutional—the decision was long and very detailed. “Lustration cannot be used to punish people as a form of revenge,” the court’s presiding judge said. The court also ruled that “an elected official cannot lose his mandate for refusing to fill in the declaration.” So Geremek’s position in the European Parliament is safe—at least for now.

But the lustration law was only one act among many in a systematic effort by the ruling Law and Justice party and its supporters to undermine the country’s democratic institutions. Since their election victory in 2005, the Kaczyńskis and their governing coalition have attempted to blur the separation of powers in order to strengthen the executive branch they control. The president, the prime minister, and the secretary of justice have attacked the independence of the courts in several ways: by publicly challenging any verdict they don’t like; by showing disrespect for the Constitutional Court, including suggestions that its judges are biased; and by the government’s rhetoric of fear and danger, which serves to justify its increase in criminal penalties and its criminalizing of acts that were previously considered civil offenses.

In the ministries and state institutions, numerous civil servants have been summarily replaced by unqualified but loyal newcomers. The independence of the mass media—especially of public radio and television—was curtailed by changes in personnel instigated by the government and by pressures to control the content of what was published and broadcast. The Kaczyński administration’s efforts to centralize power have limited both the activities of the independent groups that make up civil society and the autonomy of local and regional government. The everyday language of politics has become one of confrontation, recrimination, and accusations.

What is happening in Poland, the country where communism’s downfall began? Most revolutions have two phases. First comes a struggle for freedom, then a struggle for power. The first makes the human spirit soar and brings out the best in people. The second unleashes the worst: envy, intrigue, greed, suspicion, and the urge for revenge.

The Polish Solidarity revolution followed an unusual course. Solidarity was pushed underground when the Communist government declared martial law in December 1981. It was then that Geremek and ten thousand other Solidarity activists were arrested and imprisoned. But the movement survived seven years of repression and returned in 1989 following the spread of Gorbachev’s perestroika. During the Round Table negotiations that year between the reform wing of the Communist government and Solidarity, a compromise was reached that brought an end to Communist rule. This cleared a path to the peaceful dismantling of the Communist dictatorship throughout the entire Sovietbloc.

Solidarity adopted a philosophy of reconciliation and compromise among previously opposed political forces rather than revenge; it embraced the idea of a Poland for everyone rather than a state divided between omnipotent winners and oppressed losers. Since 1989, governments have changed, but the state remained stable; even the former Communists—now called post- Communists—approved the rules of parliamentary democracy and a market economy.

Advertisement

But not everyone accepted this path. Today, Poland is ruled by a coalition of three parties: post-Solidarity revanchists of the Law and Justice party; post-Communist provincial trouble-makers of the Self-Defense Party; and the heirs of pre–World War II chauvinist, xenophobic, and anti-Semitic groups that form the League of Polish Families. That coalition is supported by Radio Maryja, a Catholic nationalist radio station and media group that is fundamentalist both in its ethnic Polish nationalism and its commitment to Polish Catholic clericalism. In the top positions of power are the Kaczyński twins, who took part in the Solidarity movement in the 1980s and in the early post-Communist years, but who rejected the path of compromise when they founded the Law and Justice party with an extreme nationalist program.

Why is this happening? Every successful revolution creates winners and losers. Poland’s revolution brought civil rights along with increased criminality, a market economy along with failed enterprises and high unemployment, and the formation of a dynamic middle class along with increased income inequality. It opened Poland to Europe, but also brought a fear of foreigners and an invasion of Western mass culture.

For the losers of Poland’s revolution of 1989, freedom has brought great uncertainty. Solidarity workers, previously employed in relatively secure jobs at giant enterprises, have themselves become victims of the freedoms they won. In the prison world of communism, a person was the property of the state, but the state took care of one’s existence. In the world of freedom, nobody provides care. It is in this atmosphere of anxiety that the current coalition rules, employing a peculiar mix of the conservative rhetoric of George W. Bush and the authoritarian political practice of Vladimir Putin. In their attacks on the independent press, curtailment of civil society, centralization of power, and exaggeration of external and internal dangers, the political styles of today’s leaders of Poland and Russia are very similar.

The veterans of Solidarity believed that following the demise of the Communist dictatorship they would triumph. But in the spirit of reconciliation, guilty Communists were not punished, and virtuous Solidarity activists were not rewarded. Under earlier “lustration” laws adopted in the 1990s, for example, only top officials were vetted. They had to declare whether in the past they had been collaborators of the secret police. If they were found to have lied, they were barred from public service. These laws did not satisfy many people who did not immediately benefit from the breakdown of communism. Feelings of injustice gave rise to resentment, envy, and a destructive energy that focused on revenge against both former enemies and old friends who were successful under the new system.

Some former opponents of the Communists saw themselves as losers following the fall of the Communist regime. They refused to admit that gaining freedom from Soviet power was Poland’s greatest achievement in three hundred years. For them, Poland remained a country still ruled by the remnants of the Communist security apparatus. Such a Poland, they believed, required a moral revolution in which crimes would be punished, virtue rewarded, and injustice redeemed.

After they finally won the general election of 2005, these losers’ parties embarked on a great purge. The lustration procedures they imposed, according to early estimates, would affect 700,000 people and take seventeen years to complete. They also vowed to make public a list of names mentioned in the files of the Security Services—despite the fact that these files are notoriously unreliable.

These measures have produced a pervasive climate of fear. But not everyone has fallen silent. The Constitutional Court stood up to its responsibilities and, after repeated government efforts to postpone the court’s session and to impeach its judges, it reviewed the new law and found it unconstitutional. Cardinal Dziwisz of Kraków argued that there could be no place in Poland “for retribution, revenge, lack of respect for human dignity, and reckless accusations.” Not since the fall of communism has a Catholic cardinal used such words of condemnation.

The goals of Poland’s peaceful revolution were freedom, sovereignty, and economic reform, not a hunt for those who may have served the Communist secret police years ago. If a hunt for police agents and informers had been organized in 1990 when the democratic revolution began, neither the dramatic economic reforms of former Finance Minister Leszek Balcerowicz nor the establishment of a state governed by law would have been possible. Poland would not be in NATO or the European Union.

Advertisement

Today, two Polands confront each other. A Poland of suspicion, fear, and revenge is fighting a Poland of hope, courage, and dialogue. This second Poland—of openness and tolerance, of John Paul II and Czesław Miłosz, of my friends from the underground and from prison—must prevail. I believe that Poles will once again defend their right to be treated with dignity. The Constitutional Court’s decision gives hope that the second phase of the Polish revolution will not consume either its father, the will to freedom, or its child, the democratic state.

—May 31, 2007

(From Project Syndicate; translated from the Polish by Olga Amsterdamska and Irena Grudzinska Gross)

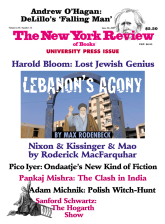

This Issue

June 28, 2007