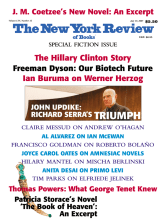

No doubt about it, the show is a triumph, the biggest interactive art event in Manhattan since Christo’s saffron flags fluttered in a wintry Central Park over two years ago. The day your reviewer attended Richard Serra Sculpture: Forty Years, a sunny Monday in June, the two large sculptures in MoMA’s Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden were crowded with young families, small children, and hopeful couples negotiating hand in hand the narrow passageways of Intersection II (1992–1993; see illustration on page 18) or jollily huddling in the crescent of shade inside the sun-baked interior space of Torqued Ellipse IV (1998).

The holiday, playground atmosphere surprised me, armed with a notebook and steeled, so to speak, to cope manfully with towering masses of metal and the great weight of art-historical importance that more timely reviewers had already assigned to the sculptor and his displayed works (“Not only our greatest sculptor but an artist whose subject is greatness befitting our time”—Peter Schjeldahl; “A landmark, by a titan of sculpture, one of the last great modernists in an age of minor talents, mad money and so much meaningless art”—Michael Kimmelman). Indeed, I was so intent on properly absorbing these marvels that I tripped over a stray toddler and nearly booted him into the rectangular, mercifully shallow pond at whose edge MoMA has posed Aristide Maillol’s silvery nude statue The River. This beloved allegorical figure, by the way, is the only customary resident of the Sculpture Garden who has not been swept away from his or her spot by the invasion of Serra’s big steel; even the trees, especially a feathery sweet locust inches from a jutting angle of Torqued Ellipse IV, look intimidated.

Surprising, too, was the wealth of textural incidents with which the twelve-foot walls of weatherproofed steel are spectacularly marked, or marred. On the two pieces outdoors in the Sculpture Garden, the weatherproofing, a brittle bluish film, is more worn off than not; lichenous orange blooms of rust have proliferated, and long rivulets of moisture have left ruddy rippling tear-trails down the slant surfaces of two-and-a-half-inch steel. Their basic coat of rust is a velvety reddish brown and looks fuzzy and eerily weightless compared with, say, David Smith’s rather implacable welded constructions—those squarish slabs of circularly burnished bare metal—and Anthony Caro’s riveted, sometimes gaudily painted beams and industrial fragments.

Serra’s early artistic training, at the University of California at Santa Barbara and then at Yale, was in painting: the fittingly massive catalog Richard Serra Sculpture: Forty Years (it accompanies the show but contains photographs of many more works than are in it) prints a conversation with the MoMA curator Kynaston McShine in which the sculptor recalls, “I ended up in my last year painting something that looked like, oh, renditions of Abstract Expressionism, somewhere between Pollock and de Kooning.” To another interviewer he has confided, “I was no slouch as a painter,” and pointed out “that he beat classmates Chuck Close and Brice Marden to a Yale traveling fellowship.” (Nor is he a slouch at theorizing; he says himself, “I came up with a generation of artists who wrote…. We had a need to write about the issues involved in our work and we wanted to encourage critical dialogue. My generation dealt with analytical language more than generations that had come before or for that matter after.”)

Surveying the many square meters of curved steel, one encounters passages of flaking waterproofing that resemble the flaky vertical canvases of Clyfford Still, and other sections as luminously blobby and drippy as oils by Sam Francis. The striped stains of Morris Louis also come to mind. One would like to know how many of these picturesque effects were the blind work of weather and accident (bumptious youngsters have left dusty sneaker-prints on lower portions of Torqued Ellipse IV and the giant crane that lifted it over the garden wall from 54th Street left marks of its clamp at the top) and how many, if any, were induced by the sculptor. Certainly Serra was not above leaving chalked numbers, Pop-style, on some of his steel plates—see the prominently displayed assemblage Five Plates, Two Poles (1971) in the East Wing of the National Gallery of Art in Washington—and a number of parallel shadows in the larger pieces at MoMA do seem more than accidental.

This Issue

July 19, 2007

-

*

The photographs of three of the large works completed in 2006 are captioned “Shown installed at Pickhan Umformtechnik GmbH, Siegen, Germany.” Kynaston McShine’s three pages of introduction include thanks to Pickhan Umformtechnik and Dillinger Hüttenwerke, Dillingen/Saar, for “their professional involvement in the making of the recent work.” The only detailed treatment of the making comes in the thirty-second footnote to Lynne Cooke’s essay on Serra’s sculptures in landscape, quoting a 1994 interview with Serra: “Basically, a forge is a hydraulic hammer which displaces metal under compression. It differs from casting in that in an equal volume, the cast will weigh one-third to one-half less than the forged work of the same measurement…. By using a magnesium and carbon steel, I found that its molecular structure, when heated to 1,280 degrees, was cubic. There was something very satisfying about dealing with a cubic structure to make a cube.” Of some outdoor blocks called Snake Eyes and Boxcars (1993), he says they “have an archaeological look in that they don’t look like steel, they look like stone. They have a burned quality like meteors or something. That has to do with the fact that we not only forged them but when they were cooling down we flamed them, so that there’s no mill-scale on them.” The “we” in “we flamed them” indicates Serra’s considerable involvement at the foundry level, and his satisfaction in molecular “cubic structure” shows a desire to dominate the process from the atomic level up.

↩