In response to:

The Supreme Court Phalanx from the September 27, 2007 issue

To the Editors:

I found Ronald Dworkin’s critique of the Supreme Court decision on racial quotas in schools [“The Supreme Court Phalanx,” NYR, September 27] interesting but I cannot understand why education boards do not just operate a lottery system. This avoids all the racial politics (and constitutional problems) that are the cause of the problem. Everyone, white or black, goes into the lottery. This should, on average, produce a representative racial distribution among desired schools (assuming whites and blacks prefer them in representative ratios).

Dworkin is perhaps naive in thinking that white families (or their kids) will ever accept losing out to a black family, as they would have it, “just because they are black.” That is the whole problem with any explicit racial test. Whatever the unfairness of the societal conditions and past discrimination, the unfairness to the “losing” white individual is too blatant to accept.

In England, education authorities in Brighton have recently begun to operate lotteries to correct for skewed school populations that harm poorer families. Good schools tend to be in high-income areas. Poor families fail to secure entry using geographical proximity criteria, hence the move to lotteries.

However nobody can argue with the roll of the dice…can they?

Daniel Wilsher

Senior Lecturer in Law

City Law School, London

Ronald Dworkin replies:

Daniel Wilsher is right that American cities should canvass a wide variety of innovative remedies in their efforts to relieve the appalling racial isolation in their public schools. I doubt, however, that the lottery he describes would be an appropriate remedy for large urban centers like Seattle and Louisville. They would face a dilemma. If the catchment areas pooled in the lottery covered only a small geographical area, that area would probably remain racially skewed and the lottery would result in continued isolation.

If, on the other hand, the pooled areas were large enough to ensure that that random selection would replicate the racial mix in the urban community as a whole, many students, both black and white, would be required to travel to schools far from their homes. Busing—probably the most unpopular strategy for relieving racial isolation ever used—would be inevitable, making the scheme politically impossible. The plans Seattle and Louisville actually adopted, which the Supreme Court struck down in a 5–4 decision because they relied partially on racial criteria, were as fair as a lottery scheme, more closely targeted to the problem, and likely to be much more effective.

Mr. Wilsher thinks me naive, however, for supposing that the plans could work: he doubts white parents could accept “losing out to a black family.” He is wrong. Of course many white families do resent programs they view as designed to aid blacks at their expense. But race-conscious plans like those Seattle and Louisville adopted have worked well across the nation, and have resulted in remarkably little intense objection.

In contrast, the Brighton lottery plan he describes—so far the only example of a lottery scheme in Britain—has generated fierce opposition in petitions, protests, and litigation (see the BBC report “Debate Over School Lottery,” news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/ uk_news/england/sussex/6745069.stm), and was widely predicted to be ineffective (see the EducationGuardian report, “Tories Attack Council’s Plan to Allocate School Places by Lottery,” education.guardian.co .uk/schools/story/0,,2023208,00.html). An adjudicator finally approved the lottery plan but only on a one-year trial basis. It seems that people can indeed “argue with the roll of the dice” when they think that their children’s privileges are at stake.

This Issue

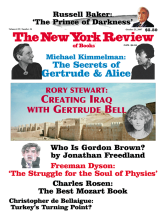

October 25, 2007