Darryl Pinckney

In the fall of 1973, she told her creative writing students at Barnard College, “There are really only two reasons to write: desperation or revenge.” She used to tell us that we couldn’t be writers if we couldn’t be told no, if we couldn’t take rejection. We supposed, therefore, that the tone she took with us was merely to get us ready: “I’d rather shoot myself than read that again.” That writing could not be taught was clear from the way she shrugged her shoulder and lifted her beautiful eyes after this or that student effort. However, a passion for reading could be shared, week after week. “The only way to learn to write is to read.” She brought in Boris Pasternak’s Safe Conduct, translated by Beatrice Scott. She said she hated to do something so “pre-Gutenberg,” and then began to read to us in a voice that was surprisingly high, loud, and suddenly very Southern:

The beginning of April surprised Moscow in the white stupor of returning winter. On the seventh it began to thaw for the second time, and on the fourteenth when Mayakovsky shot himself, not everyone had yet become accustomed to the novelty of spring.

When she got to the line about the black velvet of the talent in himself, she stopped and threw herself back in her chair, curls trembling. Either we got it or we didn’t, but it was clear from the way she struck her breastbone that to get it was, for her, the gift of life.

Sometimes she read in order to write, in order to begin, to find her way in. She agreed with Virginia Woolf that to read poetry before you wrote could open the mind. She typed at a desk upstairs in her apartment on West 67th Street; she typed at her heavy machine on the dining room table. She wrote in big handwriting on legal pads that then waited on end tables for her doubts; she wrote in little notebooks that she tucked between the cushions of the red velvet sofa. When she wrote, books piled up all around her, opened, or face down, each asking questions of her, whispering about the way in.

She remembered Hannah Arendt visiting Mary McCarthy in Maine. Arendt was lying on a sofa, with her arms behind her head, staring at the ceiling. “What’s she doing?” she remembered asking. “She’s thinking,” her old friend Mary answered. She said she felt not a little put in her place. She said she envied those who could compose in their heads. She, however, did not know what she thought until she’d written it down. She said her first drafts always read as if they’d been written by a chicken. But when she revised, she did not question why she had chosen this life. She said that writing was almost a physical process and she could never understand why she could do it on, say, Tuesday, but not on Friday. She worked all the time, thinking about what she was doing, chin on hand, or, during the Golden Age of Smoking, cigarette poised between thumb and index finger, palm turned upward. She sat there until she found her way in, until she got it right, until it was finished.

She said what she liked most was cleaning up afterward, putting the books away, dispensing with the worksheets. Her chores distracted from the anxious wait until Robert Silvers called her and this great ally of her art never kept her waiting long. She said the problem with writing anything, poem, essay, or novel, was that once you were finished, you had to do it all over again, had to start on something new. Writing was not a collaboration. In the solitude of the blank page, everyone was up against the limits of himself or herself.

After Robert Lowell was gone, she said what she minded most was everyone forgetting how hard Harriet’s father worked. He gave her the name Old Campaigner. To call her Old Campaigner, to remind her of the honor, never failed to bring forth that smile. Maybe he’d been thinking of the girl holding hands with her father and weeping in front of the radio down there in Kentucky the night Joe Louis lost. She said the faithful didn’t know what hit them when she let them have it over the Moscow trials. Up from Trotsky in Lexington, out of John Donne in Morningside Heights, this white girl novelist of the misunderstood, lipstick terror of Partisan Review. Old Campaigner, the wife and understander who refused to go with him to visit Ezra Pound.

“All air and nerve, like nobody’s business,” her best friend Barbara Epstein used to say. She warned against perfectionism. She said it was self-sabotage; it only looked like genius. She cursed her perfectionism. Yet it cannot be imitated, the miraculous purity of her style, the soulfulness of her voice:

Advertisement

Oh, M, when I think of the people I have buried. And what of “the dreadful cry of murdered men in forests.” Tell me, dear M, why it is that we cannot keep the note of irony, the tinkle of carelessness at a distance? Sentences in which I have tried for a certain light tone—many of those have to do with events, upheavals, destructions that caused me to weep like a child. Some removals I have not gotten over and I am, like everyone else, an amputee. (Why do I put in “like everyone else”? I fear that if I say that I am an amputee, and more so than anyone else, I will be embarrassing, over-reaching, yet in my heart I do believe I am more damaged than most.)

O you could not know

That such swift fleeing

No soul foreseeing—

Not even I—would undo me so!I hate the glossary, the concordance of truth that some have about my real life—have like an extra pair of spectacles. I mean that such fact is to me a hindrance to composition. Otherwise I love to be known by those I care for and consequently am always on the phone, always writing letters, always waking up to address myself to B. and D. and E.—those whom I dare not ring up until the morning and yet must talk to throughout the night.

Now, my novel begins. No, now I begin my novel—and yet I cannot decide whether to call myself I or she.*

Joan Didion

Maybe the most surprising thing I ever heard in connection with Elizabeth Hardwick wasn’t said to me by her. She was, someone else said, the person to whom he most liked to talk in the world. That was not on the face of it a surprising thing to hear about her: a lot of us felt the same way.

What was surprising was who said it.

Who said it was Peter Wolf, lead vocalist and front man for the J. Geils Band.

Lizzie had a lot of surprises, a lot of interesting curves. She remains the only writer I have ever read whose perception of what it means to be a woman and a writer seems in every way authentic, entirely original, and yet acutely recognizable. She understood at the bone the willful transgression implicit in the literary enterprise—knew that to express oneself was to expose oneself, that to seize the stage was to court humiliation—and she accepted the risk. Every line she wrote suggested that moral courage required trusting one’s own experience in the world, one’s own intuitions about how it worked.

She created a voice that carried the strength of that moral courage. A way of putting words together that could make the most subtle connection seem at once thrilling and matter-of-fact, subversively domestic, the quick stunning judgments of the kitchen. In Seduction and Betrayal, our sympathies are seen to stray from the spurned wife in The Master Builder because “depression is boring, suspicion is deforming, ill health is repetitive.” Catherine in Wuthering Heights is seen to have “the charm of a wayward schizophrenic girl.” The daunting persistence of Bloomsbury as a literary ideal is briskly dismissed: “To see the word ‘Ottoline’ on a page …gives me the sense of continual defeat, as if I had gone to a party and found an enemy attending the bar.”

She never took for granted what is often presented as a given. In Seduction and Betrayal, for example, she located Virginia Woolf’s special and claustral narrowness, her aggravated femininity, less in her situation as a woman than in the aestheticism and androgyny of Bloomsbury. She saw the source of Sylvia Plath’s destructiveness not in her time and gender but in her “lack of national and local roots,” her “foreign ancestors on both sides,” her peculiar and—once one has had it pointed out—quite unmistakable deracination.

Elizabeth Hardwick understood both sides of what it means to be deracinated, because she was not. She was born in Kentucky and grew up in Lexington. She no longer lived that life but she remembered it all. “In the summer the great bands arrived,” she remembered in Sleepless Nights.

Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Chick Webb…. They were part of the summer nights and the hot dog stands, the fetid swimming pool heavy with chlorine, the screaming roller coaster, the old rain-splintered picnic tables, the broken iron swings. And the bands were also part of Southern drunkenness, couples drinking Coke and whiskey, vomiting, being unfaithful, lovelorn, frantic.

Although she had lived in the North since she came up to Columbia for graduate school, you could still hear Kentucky in her voice, not only in her eccentric rhythms but in the extreme gravity of her remembered world, in its destructive romanticism, in its dramatic promises of redemption. “Yes I accept Jesus Christ as my personal Savior on the west side of town in June, accept Christ once more in the scorched field in the North End in July, and then again on the campgrounds to the south in August,” she wrote in Sleepless Nights. “Perhaps here began a sympathy for the victims of sloth and recurrent mistakes.”

Advertisement

So intense was her absorption in displays of recurrent mistakes that she followed certain criminal cases more raptly than did members of their own legal teams. She could deconstruct—and did, for readers of The New York Review—not only the O.J. Simpson case but the cases of the Menendez brothers, who were on trial in Los Angeles for what came to seem a couple of years, accused of murdering their mother and father at home in Beverly Hills. She took the same enchanted interest in the lives of people she actually knew. In 1985, when Darryl Pinckney suggested during a Paris Review interview that she did not like to talk about herself, she gently set the record straight: “Well, I do a lot of talking and the ‘I’ is not often absent. In general I’d rather talk about other people. Gossip, or as we gossips like to say, character analysis.”

Around the time Sleepless Nights was published, Richard Locke—in an interview with Lizzie for The New York Times Book Review—asked the source of her attraction to the lives of people who lived in Times Square hotels and rooming houses on upper Broadway. Her answer was this:

I guess I’m very much drawn, in thought, to drifters, to frauds, to working-class people, waitresses, 10-cent store clerks, bus stations. Maybe it comes from living so long in a fairly small town and spending as much time as I could on Main Street…. I have no attraction to dissipation and disorder for myself. First of all, it would conflict with my other obsessions, such as getting up early in the morning to read the newspaper out of fear of having missed something during the night…. I just like to think about the flow of the life of the unsteady, think about all those people in automobiles, driving about with their debts.

Yet her own life, as she pointed out, was the polar opposite of the unsteady. She loved her work. She loved her family. I remember a Thanksgiving, maybe 1987, when we all had dinner at Barbara Epstein’s, on West 67th Street—Lizzie and Harriet, John and Quintana and me, Barbara and Helen and Murray and Jason. Jason cooked. I endeavored to help him, without much success on the helping front. Finally we sat down in the big sitting room and ate smoked salmon canapés and drank champagne and engaged in the usual amount of character analysis. When we left Barbara’s that day John and Quintana and I walked down to the apartment we had on West 58th Street, and Quintana exactly described the occasion. “That made a nice family,” she said.

And it did.

Anywhere Lizzie was made a nice family.

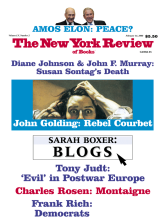

This Issue

February 14, 2008

-

*

From “Writing a Novel,” published in The New York Review, October 18, 1973. The excerpt was the opening of a semi-autobiographical work that later became Sleepless Nights, which was first published in 1979 and has been reissued by New York Review Books.

↩