The first work by Hannah Arendt that I read, at the age of sixteen, was Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil.1 It remains, for me, the emblematic Arendt text. It is not her most philosophical book. It is not always right; and it is decidedly not her most popular piece of writing. I did not even like the book myself when I first read it—I was an ardent young Socialist-Zionist and Arendt’s conclusions profoundly disturbed me. But in the years since then I have come to understand that Eichmann in Jerusalem represents Hannah Arendt at her best: attacking head-on a painful topic; dissenting from official wisdom; provoking argument not just among her critics but also and especially among her friends; and above all, disturbing the easy peace of received opinion. It is in memory of Arendt the “disturber of the peace” that I want to offer a few thoughts on a subject which, more than any other, preoccupied her political writings.

In 1945, in one of her first essays following the end of the war in Europe, Hannah Arendt wrote that “the problem of evil will be the fundamental question of postwar intellectual life in Europe—as death became the fundamental problem after the last war.”2 In one sense she was, of course, absolutely correct. After World War I Europeans were traumatized by the memory of death: above all, death on the battlefield, on a scale hitherto unimaginable. The poetry, fiction, cinema, and art of interwar Europe were suffused with images of violence and death, usually critical but sometimes nostalgic (as in the writings of Ernst Jünger or Pierre Drieu La Rochelle). And of course the armed violence of World War I leached into civilian life in interwar Europe in many forms: paramilitary squads, political murders, coups d’état, civil wars, and revolutions.

After World War II, however, the worship of violence largely disappeared from European life. During this war violence was directed not just against soldiers but above all against civilians (a large share of the deaths during World War II occurred not in battle but under the aegis of occupation, ethnic cleansing, and genocide). And the utter exhaustion of all European nations—winners and losers alike—left few illusions about the glory of fighting or the honor of death. What did remain, of course, was a widespread familiarity with brutality and crime on an unprecedented scale. The question of how human beings could do this to each other—and above all the question of how and why one European people (Germans) could set out to exterminate another (Jews)—were, for an alert observer like Arendt, self-evidently going to be the obsessive questions facing the continent. That is what she meant by “the problem of evil.”

In one sense, then, Arendt was of course correct. But as so often, it took other people longer to grasp her point. It is true that in the aftermath of Hitler’s defeat and the Nuremberg trials lawyers and legislators devoted much attention to the issue of “crimes against humanity” and the definition of a new crime—“genocide”—that until then had not even had a name. But while the courts were defining the monstrous crimes that had just been committed in Europe, Europeans themselves were doing their best to forget them. And in that sense at least, Arendt was wrong, at least for a while.

Far from reflecting upon the problem of evil in the years that followed the end of World War II, most Europeans turned their heads resolutely away from it. Today we find this difficult to understand, but the fact is that the Shoah—the attempted genocide of the Jews of Europe—was for many years by no means the fundamental question of postwar intellectual life in Europe (or the United States). Indeed, most people—intellectuals and others—ignored it as much as they could. Why?

In Eastern Europe there were four reasons. In the first place, the worst wartime crimes against the Jews were committed there; and although those crimes were sponsored by Germans, there was no shortage of willing collaborators among the local occupied nations: Poles, Ukrainians, Latvians, Croats, and others. There was a powerful incentive in many places to forget what had happened, to draw a veil over the worst horrors.3 Secondly, many non-Jewish East Europeans were themselves victims of atrocities (at the hands of Germans, Russians, and others) and when they remembered the war they did not typically think of the agony of their Jewish neighbors but of their own suffering and losses.

Thirdly, most of Central and Eastern Europe came under Soviet control by 1948. The official Soviet account of World War II was of an anti-fascist war—or, within the Soviet Union, a “Great Patriotic War.” For Moscow, Hitler was above all a fascist and a nationalist. His racism was much less important. The millions of dead Jews from the Soviet territories were counted in Soviet losses, of course, but their Jewishness was played down or even ignored, in history books and public commemorations. And finally, after a few years of Communist rule, the memory of German occupation was replaced by that of Soviet oppression. The extermination of the Jews was pushed even deeper into the background.

Advertisement

In Western Europe, even though circumstances were quite different, there was a parallel forgetting. The wartime occupation—in France, Belgium, Holland, Norway, and, after 1943, Italy—was a humiliating experience and postwar governments preferred to forget collaboration and other indignities and emphasize instead the heroic resistance movements, national uprisings, liberations, and martyrs. For many years after 1945 even those who knew better—like Charles de Gaulle—deliberately contributed to a national mythology of heroic suffering and courageous mass resistance. In postwar West Germany too, the initial national mood was one of self-pity at Germans’ own suffering. And with the onset of the cold war and a change of enemies, it became inopportune to emphasize the past crimes of present allies. So no one—not Germans, not Austrians, not French or Dutch or Belgians or Italians—wanted to recall the suffering of the Jews or the distinctive evil that had brought it about.

That is why, to take a famous example, when Primo Levi took his Auschwitz memoir Se questo è un uomo to the major Italian publisher Einaudi in 1946 it was rejected out of hand. At that time, and for some years to come, it was Bergen-Belsen and Dachau, not Auschwitz, which stood for the horror of Nazism; the emphasis on political deportees rather than racial ones conformed better to reassuring postwar accounts of wartime national resistance. Levi’s book was eventually published, but in just 2,500 copies by a small local press. Hardly anyone bought it; many copies of the book were remaindered in a warehouse in Florence and destroyed in the great flood there in 1966.

I can confirm the lack of interest in the Shoah in those years from my own experience, growing up in England—a victorious country that had never been occupied and thus had no complex about wartime crimes. But even in England the subject was never much discussed—in school or in the media. As late as 1966, when I began to study modern history at Cambridge University, I was taught French history—including the history of Vichy France—with almost no reference to Jews or anti-Semitism. No one was writing about the subject. Yes, we studied the Nazi occupation of France, the collaborators at Vichy, and French fascism. But nothing we read, in English or French, engaged the problem of France’s role in the Final Solution.

And even though I am Jewish and members of my own family had been killed in the death camps, I did not think it strange back then that the subject passed unmentioned. The silence seemed quite normal. How does one explain, in retrospect, this willingness to accept the unacceptable? Why does the abnormal come to seem so normal that we don’t even notice it? Probably for the depressingly simple reason that Tolstoy provides in Anna Karenina: “There are no conditions of life to which a man cannot get accustomed, especially if he sees them accepted by everyone around him.”

Everything started to change after the Sixties, for many reasons: the passage of time, the curiosity of a new generation, and perhaps, too, a slackening of international tension.4 West Germany above all, the nation primarily responsible for the horrors of Hitler’s war, was transformed in the course of a generation into a people uniquely conscious of the enormity of its crimes and the scale of its accountability. By the 1980s the story of the destruction of the Jews of Europe was becoming increasingly familiar in books, in cinema, and on television. Since the 1990s and the end of the division of Europe, official apologies, national commemoration sites, memorials, and museums have become commonplace; even in post-Communist Eastern Europe the suffering of the Jews has begun to take its place in official memory.

Today, the Shoah is a universal reference. The history of the Final Solution, or Nazism, or World War II is a required course in high school curriculums everywhere. Indeed, there are schools in the US and even Britain where such a course may be the only topic in modern European history that a child ever studies. There are now countless records and retellings and studies of the wartime extermination of the Jews of Europe: local monographs, philosophical essays, sociological and psychological investigations, memoirs, fictions, feature films, archives of interviews, and much else. Hannah Arendt’s prophecy would seem to have come true: the history of the problem of evil has become a fundamental theme of European intellectual life.

Advertisement

So now everything is all right? Now that we have looked into the dark past, called it by its name, and sworn that it must never again be repeated? I am not so sure. Let me suggest five difficulties that arise from our contemporary preoccupation with the Shoah, with what every schoolchild now calls “the Holocaust.” The first difficulty concerns the dilemma of incompatible memories. Western European attention to the memory of the Final Solution is now universal (though for understandable reasons less developed in Spain and Portugal). But the “eastern” nations that have joined “Europe” since 1989 retain a very different memory of World War II and its lessons, for the reasons I have suggested.

Indeed, with the disappearance of the Soviet Union and the resulting freedom to study and discuss the crimes and failures of communism, greater attention has been paid to the ordeal of Europe’s eastern half, at the hands of Germans and Soviets alike. In this context, the Western European and American emphasis upon Auschwitz and Jewish victims sometimes provokes an irritated reaction. In Poland and Romania, for example, I have been asked—by educated and cosmopolitan listeners—why Western intellectuals are so particularly sensitive to the mass murder of Jews. What of the millions of non-Jewish victims of Nazism and Stalinism? Why is the Shoah so very distinctive? There is an answer to that question; but it is not self-evident to everyone east of the Oder-Neisse line. We in the US or Western Europe may not like that but we should remember it. On such matters Europe is very far from united.

A second difficulty concerns historical accuracy and the risks of overcompensation. For many years, Western Europeans preferred not to think about the wartime sufferings of the Jews. Now we are encouraged to think about those sufferings all the time. For the first decades after 1945 the gas chambers were confined to the margin of our understanding of Hitler’s war. Today they sit at the very center: for today’s students, World War II is about the Holocaust. In moral terms that is as it should be: the central ethical issue of World War II is “Auschwitz.” But for historians this is misleading. For the sad truth is that during World War II itself, many people did not know about the fate of the Jews and if they did know they did not much care. There were only two groups for whom World War II was above all a project to destroy the Jews: the Nazis and the Jews themselves. For practically everyone else the war had quite different meanings: they had troubles of their own.

And so, if we teach the history of World War II above all—and sometimes uniquely—through the prism of the Holocaust, we may not always be teaching good history. It is hard for us to accept that the Holocaust occupies a more important role in our own lives than it did in the wartime experience of occupied lands. But if we wish to grasp the true significance of evil—what Hannah Arendt intended by calling it “banal”—then we must remember that what is truly awful about the destruction of the Jews is not that it mattered so much but that it mattered so little.

My third problem concerns the concept of “evil” itself. Modern secular society has long been uncomfortable with the idea of “evil.” We prefer more rationalistic and legal definitions of good and bad, right and wrong, crime and punishment. But in recent years the word has crept slowly back into moral and even political discourse.5 However, now that the concept of “evil” has reentered our public language we don’t know what to do with it. We have become confused.

On the one hand the Nazi extermination of the Jews is presented as a singular crime, an evil never matched before or since, an example and a warning: “Nie Wieder! Never again!” But on the other hand we invoke that same (“unique”) evil today for many different and far from unique purposes. In recent years politicians, historians, and journalists have used the term “evil” to describe mass murder and genocidal outcomes everywhere: from Cambodia to Rwanda, from Turkey to Serbia, from Bosnia to Chechnya, from the Congo to Sudan. Hitler himself is frequently conjured up to denote the “evil” nature and intentions of modern dictators: we are told there are “Hitlers” everywhere, from North Korea to Iraq, from Syria to Iran. And we are all familiar with President George W. Bush’s “axis of evil,” a self-serving abuse of the term which has contributed greatly to the cynicism it now elicits.

Moreover, if Hitler, Auschwitz, and the genocide of the Jews incarnated a unique evil, why are we constantly warned that they and their like could happen anywhere, or are about to happen again? Every time someone smears anti-Semitic graffiti on a synagogue wall in France we are warned that “the unique evil” is with us once more, that it is 1938 all over again. We are losing the capacity to distinguish between the normal sins and follies of mankind—stupidity, prejudice, opportunism, demagogy, and fanaticism—and genuine evil. We have lost sight of what it was about twentieth-century political religions of the extreme left and extreme right that was so seductive, so commonplace, so modern, and thus so truly diabolical. After all, if we see evil everywhere, how can we be expected to recognize the real thing? Sixty years ago Hannah Arendt feared that we would not know how to speak of evil and that we would therefore never grasp its significance. Today we speak of “evil” all the time—but with the same result, that we have diluted its meaning.

My fourth concern bears on the risk we run when we invest all our emotional and moral energies into just one problem, however serious. The costs of this sort of tunnel vision are on tragic display today in Washington’s obsession with the evils of terrorism, its “Global War on Terror.” The question is not whether terrorism exists: of course it exists. Nor is it a question of whether terrorism and terrorists should be fought: of course they should be fought. The question is what other evils we shall neglect—or create—by focusing exclusively upon a single enemy and using it to justify a hundred lesser crimes of our own.

The same point applies to our contemporary fascination with the problem of anti-Semitism and our insistence upon its unique importance. Anti-Semitism, like terrorism, is an old problem. And as with terrorism, so with anti-Semitism: even a minor outbreak reminds us of the consequences in the past of not taking it seriously enough. But anti-Semitism, like terrorism, is not the only evil in the world and must not be an excuse to ignore other crimes and other suffering. The danger of abstracting “terrorism” or anti-Semitism from their contexts—of setting them upon a pedestal as the greatest threat to Western civilization, or democracy, or “our way of life,” and targeting their exponents for an indefinite war—is that we shall overlook the many other challenges of the age.

On this, too, Hannah Arendt had something to say. Having written the most influential book on totalitarianism she was well aware of the threat that it posed to open societies. But in the era of the cold war, “totalitarianism,” like terrorism or anti-Semitism today, was in danger of becoming an obsessive preoccupation for thinkers and politicians in the West, to the exclusion of everything else. And against this, Arendt issued a warning which is still relevant today:

The greatest danger of recognizing totalitarianism as the curse of the century would be an obsession with it to the extent of becoming blind to the numerous small and not so small evils with which the road to hell is paved.6

My final worry concerns the relationship between the memory of the European Holocaust and the state of Israel. Ever since its birth in 1948, the state of Israel has negotiated a complex relationship to the Shoah. On the one hand the near extermination of Europe’s Jews summarized the case for Zionism. Jews could not survive and flourish in non-Jewish lands, their integration and assimilation into European nations and cultures was a tragic delusion, and they must have a state of their own. On the other hand, the widespread Israeli view that the Jews of Europe conspired in their own downfall, that they went, as it was said, “like lambs to the slaughter,” meant that Israel’s initial identity was built upon rejecting the Jewish past and treating the Jewish catastrophe as evidence of weakness: a weakness that it was Israel’s destiny to overcome by breeding a new sort of Jew.7

But in recent years the relationship between Israel and the Holocaust has changed. Today, when Israel is exposed to international criticism for its mistreatment of Palestinians and its occupation of territory conquered in 1967, its defenders prefer to emphasize the memory of the Holocaust. If you criticize Israel too forcefully, they warn, you will awaken the demons of anti-Semitism; indeed, they suggest, robust criticism of Israel doesn’t just arouse anti-Semitism. It is anti-Semitism. And with anti-Semitism the route forward—or back—is open: to 1938, to Kristallnacht, and from there to Treblinka and Auschwitz. If you want to know where it leads, they say, you have only to visit Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, the Holocaust Museum in Washington, or any number of memorials and museums across Europe.

I understand the emotions behind such claims. But the claims themselves are extraordinarily dangerous. When people chide me and others for criticizing Israel too forcefully, lest we rouse the ghosts of prejudice, I tell them that they have the problem exactly the wrong way around. It is just such a taboo that may itself stimulate anti-Semitism. For some years now I have visited colleges and high schools in the US and elsewhere, lecturing on postwar European history and the memory of the Shoah. I also teach these topics in my university. And I can report on my findings.

Students today do not need to be reminded of the genocide of the Jews, the historical consequences of anti-Semitism, or the problem of evil. They know all about these—in ways their parents never did. And that is as it should be. But I have been struck lately by the frequency with which new questions are surfacing: “Why do we focus so on the Holocaust?” “Why is it illegal [in certain countries] to deny the Holocaust but not other genocides?” “Is the threat of anti-Semitism not exaggerated?” And, increasingly, “Doesn’t Israel use the Holocaust as an excuse?” I do not recall hearing those questions in the past.

My fear is that two things have happened. By emphasizing the historical uniqueness of the Holocaust while at the same time invoking it constantly with reference to contemporary affairs, we have confused young people. And by shouting “anti-Semitism” every time someone attacks Israel or defends the Palestinians, we are breeding cynics. For the truth is that Israel today is not in existential danger. And Jews today here in the West face no threats or prejudices remotely comparable to those of the past—or comparable to contemporary prejudices against other minorities.

Imagine the following exercise: Would you feel safe, accepted, welcome today as a Muslim or an “illegal immigrant” in the US? As a “Paki” in parts of England? A Moroccan in Holland? A beur in France? A black in Switzerland? An “alien” in Denmark? A Romanian in Italy? A Gypsy anywhere in Europe? Or would you not feel safer, more integrated, more accepted as a Jew? I think we all know the answer. In many of these countries—Holland, France, the US, not to mention Germany—the local Jewish minority is prominently represented in business, the media, and the arts. In none of them are Jews stigmatized, threatened, or excluded.

If there is a threat that should concern Jews—and everyone else—it comes from a different direction. We have attached the memory of the Holocaust so firmly to the defense of a single country—Israel—that we are in danger of provincializing its moral significance. Yes, the problem of evil in the last century, to invoke Arendt once again, took the form of a German attempt to exterminate Jews. But it is not just about Germans and it is not just about Jews. It is not even just about Europe, though it happened there. The problem of evil—of totalitarian evil, or genocidal evil—is a universal problem. But if it is manipulated to local advantage, what will then happen (what is, I believe, already happening) is that those who stand at some distance from the memory of the European crime—because they are not Europeans, or because they are too young to remember why it matters—will not understand how that memory relates to them and they will stop listening when we try to explain.

In short, the Holocaust may lose its universal resonance. We must hope that this will not be the case and we need to find a way to preserve the core lesson that the Shoah really can teach: the ease with which people—a whole people—can be defamed, dehumanized, and destroyed. But we shall get nowhere unless we recognize that this lesson could indeed be questioned, or forgotten: the trouble with lessons, as the Gryphon observed, is that they really do lessen from day to day. If you do not believe me, go beyond the developed West and ask what lessons Auschwitz teaches. The responses are not very reassuring.

There is no easy answer to this problem. What seems obvious to West Europeans today is still opaque to many East Europeans, just as it was to West Europeans themselves forty years ago. Moral admonitions from Auschwitz that loom huge on the memory screen of Europeans are quite invisible to Asians or Africans. And, perhaps above all, what seems self-evident to people of my generation is going to make diminishing sense to our children and grandchildren. Can we preserve a European past that is now fading from memory into history? Are we not doomed to lose it, if only in part?

Maybe all our museums and memorials and obligatory school trips today are not a sign that we are ready to remember but an indication that we feel we have done our penance and can now begin to let go and forget, leaving the stones to remember for us. I don’t know: the last time I visited Berlin’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, bored schoolchildren on an obligatory outing were playing hide-and-seek among the stones. What I do know is that if history is to do its proper job, preserving forever the evidence of past crimes and everything else, it is best left alone. When we ransack the past for political profit—selecting the bits that can serve our purposes and recruiting history to teach opportunistic moral lessons—we get bad morality and bad history.

Meanwhile, we should all of us perhaps take care when we speak of the problem of evil. For there is more than one sort of banality. There is the notorious banality of which Arendt spoke—the unsettling, normal, neighborly, everyday evil in humans. But there is another banality: the banality of overuse—the flattening, desensitizing effect of seeing or saying or thinking the same thing too many times until we have numbed our audience and rendered them immune to the evil we are describing. And that is the banality—or “banalization”—that we face today.

After 1945 our parents’ generation set aside the problem of evil because—for them—it contained too much meaning. The generation that will follow us is in danger of setting the problem aside because it now contains too little meaning. How can we prevent this? How, in other words, can we ensure that the problem of evil remains the fundamental question for intellectual life, and not just in Europe? I don’t know the answer but I am pretty sure that it is the right question. It is the question Hannah Arendt asked sixty years ago and I believe she would still ask it today.

This Issue

February 14, 2008

-

1

This article is adapted from a lecture delivered in Bremen, Germany, on November 30, 2007, on the occasion of the award to Tony Judt of the 2007 Hannah Arendt Prize.

↩ -

2

“Nightmare and Flight,” Partisan Review, Vol. 12, No. 2 (1945), reprinted in Essays in Understanding, 1930–1954, edited by Jerome Kohn (Harcourt Brace, 1994), pp. 133–135.

↩ -

3

For a harrowing instance, see Jan Gross, Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland (Princeton University Press, 2001).

↩ -

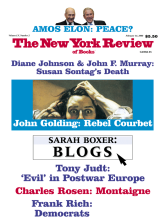

4

For a fuller discussion of this shift in mood, see the epilogue (“From the House of the Dead”) in my Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945 (Penguin, 2005).

↩ -

5

To be sure, Catholic thinkers have not shared this reluctance to engage with the dilemma of evil: see, for example, Leszek Kolakowski’s essays “The Devil in History” and “Leibniz and Job: The Metaphysics of Evil and the Experience of Evil,” both recently republished with other essays by Kolakowski in My Correct Views on Everything (St. Augustine’s, 2005; discussed in The New York Review, September 21, 2006). But in the metaphysical confrontation memorably portrayed by Thomas Mann, we moderns have typically opted for Settembrini over Naphta.

↩ -

6

Essays in Understanding, pp. 271–272.

↩ -

7

See Idith Zertal, Israel’s Holocaust and the Politics of Nationhood, translated by Chaya Galai (Cambridge University Press, 2005), especially Chapter 1, “The Sacrificed and the Sanctified.”

↩