In the early nineteenth century, if a bird came into view and a hunter fired without having time to aim deliberately, the hunter was said to have taken a snapshot. According to The Oxford English Dictionary, Sir John Herschel applied the term to photography in 1860. Herschel, who also coined the word “photographic,” was speculating about future possibilities; at the time, it was difficult to act on a sudden picture-taking impulse. Many cameras were bulky, because they had to be large enough to hold the chemically treated metal or paper that was sensitive to light and either matched in size, or itself became, the image finally displayed.

The chemistry involved was also cumbersome, though there were several processes to choose from. Before taking a daguerreotype, a photographer had to fumigate with iodine a silver-plated sheet of copper. In the British technique of calotypy, paper negatives were coated with silver nitrate, dried, and stored ahead of time, allowing a limited degree of spontaneity for those who prepared in advance. But the paper’s fibers blurred the image. Many therefore preferred the wet-collodion process, in which a glass plate was covered with a sticky, transparent substance, soaked in a silver nitrate solution, loaded in a camera while still damp, and developed immediately after exposure. The results were sharp, but photographers either had to stay near a darkroom or cart a portable one around with them. No chemical preparation was then sensitive enough to record a person unwilling or unable to keep still. “Were you ever daguerreotyped, O immortal man?” Emerson asked his journal in 1841.

And in your zeal not to blur the image, did you keep every finger in its place with such energy that your hands became clenched as for fight or despair,…and the eyes fixed as they are fixed in a fit, in madness, or in death?

Yet there is arguably one photograph that can be called a snapshot in “Impressed by Light,” the recent exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art of calotypes made between 1840 and 1860. It is an 1846 picture of the grounds of a villa in Naples taken by Christopher Rice Mansel “Kit” Talbot. Known in his day as “the wealthiest commoner” in Britain, Kit Talbot came into his money by inheritance and became acquainted with photography through his cousin William Henry Fox Talbot, who invented not only calotypy but also the process of making multiple prints from a single negative. In his Naples photo, Kit left the aperture of his camera open for five minutes, so it isn’t speed that qualifies the image as a snapshot. It’s rather that he doesn’t seem to have cared whether his technique was any good.

The insouciance shows. Whereas the blur in most calotypes seems painterly—a pleasant scumble over rocks, dirt, grass, and bark, all of whose texture is finely displayed—the blur in Kit Talbot’s is just blur. Excess light erases tree trunks and most of a statue’s definition. A girl in the foreground is translucent, probably because she wandered off halfway through the exposure. So blobby are the forms that the image suggests no depth, no spatial complexity. Yet it does convey a mood—warmth and idleness in southern Italy. It charms, perhaps because the viewer senses that it was rare in 1846 to be so casual about photography. Only someone very well-to-do was likely to acquire all the equipment and yet not bother to learn how to use it properly. Kit Talbot’s effort was a glimpse of photography’s future: sloppy, emotional, chancy, and often associated with vacations.

That future was brought about in large part by a former bank clerk named George Eastman, as curator Diane Waggoner recounts in her contribution to the catalog of “The Art of the American Snapshot, 1888–1978,” the recent exhibition at Washington’s National Gallery of Art. In 1881, Eastman began selling gelatin dry plates in America. As the name suggests, dry plates didn’t have to be wet to work. They were also more sensitive to light, cutting exposure times to fractions of a second. Suddenly it was possible to capture the world impromptu. Cameras shrank, making them more portable, and manufacturers began to call the handheld ones “detective cameras.” The disc-shaped Concealed Vest Camera, one inch thick and five inches wide, fit under a gentleman’s waistcoat like an extra layer of paunch, its lens poking discreetly through a buttonhole.

Amateurs still had to develop pictures in darkrooms in their own basements, however, and relatively few were willing to work so hard for a mere pastime. Eastman’s breakthrough was to offer photographic processing as a service. In 1888, he started selling a small, boxy detective camera he called a Kodak, a made-up word perhaps inspired by his fondness for the first letter of his mother’s maiden name, Kilbourn. Neither focus nor aperture could be adjusted. Inside was a roll of paper with a light-sensitive emulsion, long enough for one hundred circular images. Once the customer finished taking pictures, she sent the unopened camera to Eastman’s factory, which developed the emulsion into negative images, transferred them to see-through gelatin, and made prints. The camera cost $25.00; a round of processing, $10.00. “You press the button,” Eastman’s ads explained, “we do the rest.” It was no longer necessary for photographers to know anything about optics or chemistry. “Anybody can use it,” an early promotional booklet boasted. “Everybody will use it.” Eastman was soon selling thousands.

Advertisement

Eastman steadily brought new technologies to market, leasing and buying patents when necessary, and his cameras became even easier to use. In 1889 he replaced paper-backed negatives with cellulose film. In 1891, he introduced a camera that could be loaded with film in daylight. In 1895 he sold a pocket camera less than four inches long. His genius, however, was for marketing, which he aimed largely at women and children. As early as 1893, Kodak ads featured a young woman known as the “Kodak Girl,” by turns stylish, free-spirited, and domestic. And in 1900, Eastman’s company released the Brownie, a one-dollar camera named after a playful community of cartoon sprites, although Eastman never paid or credited Palmer Cox, the illustrator who had first adapted the sprites from Scottish folklore and popularized them.

Eastman himself was portrayed in the promotional material for the Brownie as an amiable demiurge who reproduced for the sprites a box with the power to revive the past and record the present. As the critic Marc Olivier recently observed, the tale suggested that children could hopscotch directly from the oral world of folktales to the visual one of the twentieth century, bypassing literacy altogether.1 The air of nonthreatening magic and the low price attracted customers of all ages, and Kodak was to manufacture Brownies for the next half-century. Photography was on the way to becoming “almost as widely practiced as sex and dancing,” as Susan Sontag put it in these pages in 1973. According to one estimate, the inflation-adjusted cost of a new camera in 1939 was “almost one hundredth of that of the first Kodak camera in 1888, bringing it within the reach of virtually every home.”2

The new photographs had an appealing lack of finish. Liberated from the special chair whose metal ring had immobilized subjects’ heads from behind, people invented new, much less formal poses. In a delicate image from around 1900, included in the National Gallery’s exhibition, a young woman in a black dress sits in a patch of tall grass and leans against a white clapboard building. The grass is unruly, the clapboard is plain, and the dress, which may be a nun’s habit given the crucifix and three linked rings on the woman’s chest, is so dark that it simplifies her body almost to a silhouette. But it evokes the idea of a contemplative life in harmony with nature more strongly than any formal portrait could. Elsewhere the new freedom contributes to a sort of homemade surrealism. Half-transformed tadpoles drift in a round glass vase. Two young men in matching outfits sit Indian-style side by side in an unkempt field, holding both pairs of each other’s hands so that their arms form a W, with a wooden clothespin dropped like a clue in front of them.

“The photographer whose knowledge has been confined to pressing the button can never hope to make good pictures,” according to a camera manual of the 1890s. For a while, Waggoner explains, the serious amateur tried to maintain a distinction between his timed exposures, which were considered artful, and the snapshooter’s instantaneous ones, deemed relatively thoughtless. But film speeds improved, and soon all but a few photographs were instantaneous.

That left only skill and art. Here time has not been kind to the serious amateur, who aspired to a kind of beauty that to a modern eye looks accomplished but insipid. There are a number of examples in Anonymous: Enigmatic Images from Unknown Photographers3: moonlit forests, Paris in the fog, children posed in allegorical costumes. Because the serious amateur made a point of not compromising his images with the mundane, he is seldom of use to social historians. For documentary and aesthetic purposes, one turns instead to photographers who had no idea what they were doing—who “had the advantage of having nothing to unlearn,” as the curator and photographer John Szarkowski once put it.

These photographers made mistakes. One scholar of the snapshot has catalogued the classic ones, including a tilted horizon, unconventional cropping, eccentric framing, a distant subject, blur, double exposure, light leaks, a finger over the lens, banality, and the photographer’s shadow.4 Nearly all these features appear in the snapshots at the National Gallery of Art and in the exhibition’s catalog. In a snapshot taken around 1930, for example, a photographer appears to have tried to reproduce a Victorian-era portrait by photographing it being held by a pair of hands against an automobile door. He seems to have misjudged the framing, however, and the tiny portrait at the center of the photograph—a couple in formal dress, separated by a garden gate—appears as a mere detail, no more prominent than the large hands holding it in place. By accident, the polish of the car reflects the photographer, hunched over his device, as well as a tall, skeletal structure behind him, which might be either an electrical tower or a windmill. It fails as a reproduction, but suggests an allegory of the past’s diminished place in the present—not as reflective of us as of the glossy new surfaces of the modern world.

Advertisement

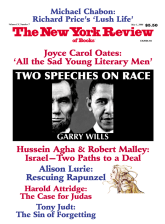

Similar effects appear—though by calculation rather than accident—in twentieth-century art photography: Garry Winogrand is famous for tilted horizons; Lee Friedlander for photographing his own shadow. Among the works included in the first installation of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s new Joyce and Robert Menschel Hall for Modern Photography,5 a 1996 portrait by Sharon Lockhart of a man in his early thirties has an offhand pose that suggests a snapshot’s casualness; his arms are akimbo, his mouth slack, and his hair stringy. He is standing in what seems to be a hotel room with plate glass windows, high above the street, and the room is projected by the glass’s reflection into the city dusk behind him. The mastery of lighting and camera angle would be hard for an amateur to match, but the style and mood of the image—posed as if unposed, as if offering a glimpse only available to an intimate or a voyeur—are clearly influenced by snapshooters. How is it that the art of photography today owes so much to those who didn’t master the technology?

Museums and art historians were slow to consider the snapshot as an influence on art, let alone as an art in itself. When New York’s Museum of Modern Art assembled its first exhibition of snapshots in 1944, it was halfhearted. The museum merely recropped and reprinted amateur photographs that had won prizes in earlier Kodak-sponsored competitions, most of them sentimental and banal. Children play in snow; young women ride horses on a beach; a man in uniform shakes a dog’s paw. Such images were effective only as advertising.

Not all snapshooters were pious about American innocence, however, and from the 1930s to the 1950s, the work of such art photographers as Helen Levitt, Sid Grossman, and William Klein revealed an interest in the beauty and drama that less conventional snapshooters found in the accidental and the everyday. Levitt, for example, photographed children at play in New York City streets, and she caught them in remarkable unposed photos such as the one in which two boys hold up an empty mirror frame on a sidewalk while a third, seated on a tricycle, looks through it at a fourth, who has bent over to sort through shards of mirror glass in the gutter. None of the children is paying any attention to the camera.

In 1964, in the Museum of Modern Art exhibition “The Photographer’s Eye,” Szarkowski placed art photographs next to news and portrait photographs by relative or complete unknowns. “One would expect the artless pictures to suffer when compared to the conscious works of art that surround them,” Janet Malcolm wrote, “but, oddly enough, they do not.” The exhibition prepared the way for serious consideration of snapshots.

The connection between art and amateur photography was at last made explicit in a 1975 issue of Aperture magazine, which published art photographs in the snapshot spirit by Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, Emmet Gowin, Tod Papageorge, and Joel Meyerowitz. Gowin was fascinated by the ability of snapshots to suggest a family’s emotional life, and contributed images of his wife’s family, who in one example loafed on a Southern lawn around a bisected watermelon. Meyerowitz’s photos were taken from his moving car, including one of a Pan Am jet flying low over a pyramid of unused concrete sewer pipes, and another of mobile homes in a seaside parking lot, beneath a strangely protuberant island on the horizon. Some of the artists suggested that the distinction between snapshots and art photography was arbitrary. “I have always taken the position that the word snapshot doesn’t really mean anything,” Paul Strand told an interviewer, and Winogrand dismissed the word as useful only for “pigeonholing photographs and photographers.”

In an essay, the critic John A. Kouwenhoven claimed that the snapshot had reshaped “our conception of what is real and therefore of what is important,” an idea that he went on to explain more fully elsewhere by commenting on a photograph he had found in one of his own family’s albums, a picture his aunt had taken in 1885 of a building in Philadelphia where her mother had once lived. Kouwenhoven imagined that his aunt must have been dismayed to find working-class idlers and horse-drawn dump trucks inadvertently included. The snapshot, however, records the historical truth in rich sociological detail whether or not sentimental aunts wish to see it.6

For all its praise of snapshots, the Aperture issue reproduced few anonymous photographs, and it was only in 1998 that the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art put on “Snapshots: The Photography of Everyday Life, 1888 to the Present.” Douglas R. Nickel, the curator, saw the art in snapshots as “a kind of afterlife” that began only “when the family history ends and the album surfaces at a flea market, photographic fair, or historical society,” as he explained in the catalog.7 Perhaps when images’ creators are safely dead and quiet, a curator has a freer hand. The photos in Nickel’s exhibition are full of subtle humor. What seems at first to be an ordinary portrait of an elementary school class in the 1920s, for example, is complicated by a boy in the back row who holds a black oval of cloth or paper in front of his face, as if to erase himself. At times the poignancy of the images is almost painful, as in one from the 1940s of a young man with a tattoo on his shoulder surprised in the bathtub, a spot of white suds on his temple, his eyes still vague with reverie. The image is blurred, perhaps because the hand of the wife or lover holding the camera was trembling.

A similar spirit was at play in “Other Pictures,” an exhibition in 2000 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art of black-and-white and sepia-toned snapshots from the 1910s through the 1960s collected by Thomas Walther.8 In one snapshot from about 1950, a Jean Arp–like composition is formed by a woman’s folded legs, loops of a garden hose, outlines of puddles the hose has left, and the droopy underpants of a child walking away. The horizon is askew, and the framing decapitates the child, but it’s evident why Walther thought it a “successful failure,” to borrow a term from curator Mia Fineman’s catalog essay. In some images, the photographer seems in on the joke, as when his hand, reaching toward a watering can, is so distorted in the metal’s reflection that it looks as if it were E.T.’s or Nosferatu’s. In others, he isn’t, as when the shadows of hunters taking a trophy photograph seem to be cornering a dead and propped-up deer.

But in almost every case the joke involved depends not on ridicule but on something unintended by the photographer—on what Fineman calls “the traces of a classic slapstick struggle between human and machine.” Some of that slapstick was openly erotic. In one example, a nude young man is so absorbed by a sheaf of papers, and the viewer’s eye so naturally drawn to what he’s looking at, that it takes a moment before the viewer catches sight of the man’s erection below, poking out at an angle parallel to his reading matter.

To the larkish tone of the exhibitions by Nickel and Walther and Fineman, the National Gallery of Art added chronology. Robert E. Jackson, a Seattle businessman, began collecting snapshots in 1997, selecting images for their inventiveness and immediacy. Waggoner and the curator Sarah Greenough chose more than two hundred of Jackson’s images and divided them into four historical periods, for which they, Sarah Kennel, and Matthew S. Witkovsky have written descriptive essays. The photos, chosen for the pleasure they give, and the text, which aims to recount photographic history, sometimes seem at odds; but the ways people took snapshots, what they took snapshots of, and how they presented themselves to the camera changed with time, and Jackson’s sample is large enough to allow speculation about the nature of the changes.

The visitor to the Washington exhibition moved through five small rooms, whose walls lightened as the pictures advanced in time, from the late nineteenth century to the late 1970s. Practically all the images were small in size. It wasn’t evident until you got close that you were looking at a man’s legs standing in heels on a chair and wrapped in a bath towel, or that the billboard that four women in Edwardian-era black were wagging their fingers at was an advertisement for cigarettes.

One senses, while looking at the late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century images, that to be photographed was then an occasion, perhaps even a treat. Subjects participate in their photographs, sometimes showing a thoughtfulness and care that must have matched the photographer’s. In one example, two young women sit facing away from the camera before a dressing-table mirror, which reflects one of them and the photographer. The second young woman’s face is reflected in a hand mirror she holds. If anyone were to move an inch, the composition would be spoiled, but the young women’s smiles are natural. It’s a game, and they’ve surrendered to the photographer’s authority the way actors surrender to a director.

In some images, the game is obvious, as when two boys put on a mother’s and a sister’s dresses and preen for the camera without a hint of embarrassment. But in others, the participants seem to be acting out an obscure charade, as when two men and two women smile at the camera with their hands jutting through paper and wearing on their heads busted cardboard boxes and crumpled wrapping paper. The curators suggest that the men and women might be acting out a visual pun on the phrase “breaking the news” (as is clearly the case with the photograph shown on the opposite page). This guess doesn’t seem quite right since there are no newspapers in sight, but the impulse to guess seems irresistible.

There’s something sphinxlike about these images, as if one were looking at dreams as yet uninterpreted. With the right clues, one feels, the images would become less mysterious, but meanwhile they lend themselves to associations. A boy burrows in three dirt holes in front of a clapboard house: Is he pretending to be a gopher? To dig up treasure? Perhaps digging some up? The pictures seem to dramatize their muteness.

Eastman released a Speed Kodak with a shutter speed of one one-thousandth of a second in 1909. In the 1920s and 1930s, many amateurs took advantage of faster shutters and faster films to catch motion, and the National Gallery of Art exhibition includes examples: a bouquet thrown overboard, a motorcycle in mid-jump (see illustration on page 48), a child tossed aloft by a parent. Blur became a sign of action, Kennel writes in her essay on changes over the decades, and was a sought-after effect. On the back of an out-of-focus snap of herself and two friends from the 1930s, a photographer describes her picture as “Modernistic” and asks, “Good?”

A theater audience may accept that the proscenium separates the real world from that of the play, but a camera does not respect such socially negotiated boundaries. The early snapshooters discovered this by accident. In an image from the first decade of the twentieth century, a patterned fabric covers from head to toe a person holding a baby, as if in hopes that the camouflage will make only the baby visible. But what we see is a baby gripped by a shrouded golem; the attempt to control what is seen is made visible along with everything else. Once this power of the camera’s is added to a willingness to see people as things, a hostility sometimes emerges between photographer and subject. In 1955, for example, when a young woman named Flo began taking snapshots of her IBM co-workers and boardinghouse roommates, her subjects tried to discourage her. They hid their faces, turned away, or stuck out their tongues; in revenge, she photographed them unawares, their rumps in the air or their heads in the sink for a shampoo. In a photograph from the 1970s, a woman with a cigarette-gray complexion resorts to giving a photographer the finger as she is presented with a birthday cake.

In many of the show’s examples from the late twentieth century, subjects appear merely resigned to having their pictures taken. Most of the photographs are set indoors. The typical face is masklike and empty, a sphinx who has forgotten her own question. When I reached the end of the exhibition, I found myself retreating to pictures taken earlier, when the sense of experiment was fresh and the sympathy between photographer and subject was not yet broken—when sailors sunbathing nude weren’t photographed until they had made themselves decent by a comic placement of their caps.

This Issue

May 1, 2008

-

1

Marc Olivier, “George Eastman’s Modern Stone-Age Family: Snapshot Photography and the Brownie,” Technology and Culture, Vol. 48, No. 1 (January 2007).

↩ -

2

Brian Coe and Paul Gates, The Snapshot Photograph: The Rise of Popular Photography, 1888–1939 (London: Ash and Grant, 1977), p. 46.

↩ -

3

Edited by Robert Flynn Johnson (Thames and Hudson), 2004).

↩ -

4

Graham King, Say “Cheese”! Looking at Snapshots in a New Way (Dodd, Mead, 1984), pp. 49–57. Dozens of snapshots with photographers’ shadows are reproduced in Jeffrey Fraenkel’s The Book of Shadows (Fraenkel Gallery/DAP, 2007). In a photo of a handsome, shirtless boy at the start of the book, the shadow of the picture taker—as young and fit as his subject, to judge by his outline—falls on the wall beside him like a companion.

↩ -

5

“Depth of Field: Modern Photography at the Metropolitan,” September 25, 2007–March 23, 2008.

↩ -

6

John A. Kouwenhoven, “Living in a Snapshot World,” Half a Truth Is Better Than None (University of Chicago Press, 1982), pp. 147–181.

↩ -

7

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1998.

↩ -

8

See Other Pictures: Anonymous Photographs from the Thomas Walther Collection, edited by Mia Fineman (Twin Palms, 2000).

↩