Of all the travel sagas ever written, none is more richly astonishing than Marco Polo’s Description of the World.* First published around 1300, it records a land of such fabulous difference that to enter it was like passing through a mirror; and it is this passage—from a still-provincial Europe to an empire of brilliant strangeness—which gives the tale even now a dream- like quality. Even in its day—and for generations afterward—Polo’s book was often regarded merely as the fairy-tale conceit of a vainglorious merchant. Only with time has its portrait of China at the height of the Mongol dynasty—a portrait rich in details that once seemed too outlandish to be believed—been largely corroborated.

Marco Polo was born in 1254 into a family of Venetian merchants, wealthy if not patrician. Even before his celebrated journey, his father and uncle had traveled from Constantinople to the Crimea, then continued some five thousand miles east to the court of Khubilai Khan—the Mongol emperor of a newly conquered China—probably at Cambalú, modern Beijing. Marco Polo describes their prodigious journey only briefly, as a prelude to his own. He records how the two men started back for Europe with a request from Khubilai that the Pope send them back to him. They were to bring with them a hundred Christian savants and some oil from the lamp above Christ’s sepulcher in Jerusalem. By the time Polo’s father arrived in Venice in 1269, after sixteen years away, his wife was dead and he had a fifteen-year-old son whom he had never seen. This was Marco.

Two years later the seventeen-year-old youth, with the two elder Polos, set out on the long journey back to Cambalú. Their route is not always easy to follow. Marco’s account, dictated almost thirty years later, is full of gaps and muddled chronology. But it seems that after visiting Acre on the coast of Palestine the Polos moved in a wide loop from eastern Turkey down through modern Iran to Hormuz on the Persian Gulf. From there they crossed Persia northeast to Balkh, in today’s Afghanistan, and over the Pamir Mountains through Kashgar to the Taklamakan desert of northwest China. Skirting this dangerous wasteland southward, they then circled north of the Yellow River to the khan’s summer palace of Xandú, and at last to Cambalú. The journey had taken three and a half years.

There follows the heart of Polo’s narrative: a portrait of Khubilai Khan’s world that is both reverential and intimate. In turn he evokes the great palaces of marble with walls sheathed in gold and silver, the curious court etiquette and sumptuous ceremonial banquets, the imperial pavilions, hunting and falconry. He describes the empire’s fiscal policy and the novel use of paper money, the khan’s easygoing religious faith, his wardrobe, his superb postal system, even the privacies of his sex life and harem.

Then, traveling south, Polo writes of the ancient Chinese regions recently subdued by the Mongols, a world epitomized by the old Sung dynasty capital of Quinsai, modern Hangzhou. Even in its captive state, this city struck him as the gentlest and most refined in the world, and its now dead ruler as a paragon of benevolence. He goes on to give valuable accounts of the Mongol conquest and of the failed invasion of Japan. Then, in an attempt to fulfill his professed purpose of describing the entire world, he broadens his canvas into sketches of the lands he touched on during his return sea journey—and of others beyond those: Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India, and beyond the Arabian Sea to Africa, even Russia.

Polo was in China for between sixteen and seventeen years, and it is from this that the value of his narrative springs. He claims to have been an Intimate of the great khan himself, and to have served as an imperial envoy, even as governor of a city. “Marco was held in high estimation and respect by all belonging to the court,” he says of himself immodestly. “He learnt in a short time and adopted the manners of the Tartars, and acquired a proficiency in four different languages….” And again (in another manuscript): “This noble youth seemed to have divine rather than human understanding.”

The fact that nobody of Polo’s name, or a similar one, is recorded in the imperial service by contemporary Chinese chronicles does not discount his claim. His duties were perhaps less official than he implies. Certainly it was a policy of Khubilai to employ able foreigners. Turkic and Persian Muslims especially, Indians and Nepalese, all served as a buffer between the Mongol overlords and their teeming Chinese subjects. The khan’s personal bodyguards were foreigners from the Caucasus and beyond. His own mother, the astute and powerful Sorghaghtani Beki, was a Nestorian Christian. Polo himself mentions mercantile quarters in Cambalú for Germans, Lombards, and French, and his family’s mission to the Mongol court had been preceded by others more formal.

Advertisement

In the mid-thirteenth century, half of Asia seemed poised precariously between Islam and Christianity. Popes and Christian kings, fearful of the Muslim pressure on Palestine, grasped for deliverance in rumors of a sympathetic Mongol power to the east. In 1245 Pope Innocent IV had sent the Franciscan friar Giovanni da Pian del Carpini to the court of the great khan at Khara Khorum (where he witnessed the enthronement of one of Khubilai’s predecessors), and in 1253 Louis IX of France had dispatched another friar, William of Rubruck. But both men returned with the same disheartening message: Let your kings come here and pay us tribute. As for Marco Polo’s character, the man who percolates through his often terse and impersonal sentences is at once sharply observant and rather naive. His intelligence, it seems, was a merchant’s: astute in practical things, energetic, and resourceful. His obsession with the pomp and refinements of court, with feasts and ceremonial, costume and luxury, is that of both a salesman and a dazzled courtier. But typical of his mother city, he was tolerant of other faiths and practices. His routine dismissal of idolatry does nothing to dim his admiration for Mongol rule and Chinese life. (“Their style of conversation is courteous…. To their parents they show the utmost reverence.”) Like a harbinger of the new age, he is endlessly intrigued by the novel and the different.

But above all, there is the matter of Polo’s integrity. Ever since it was written, his book has caused unease. Alongside verifiable fact and rigorous observation, he tosses in hearsay and credulous imaginings. A few Sinologists have even asked: Did he go to China at all? Could he have gathered his intelligence from elsewhere?

In his Description Polo tells at least one outrageous lie. At the Mongol siege of the “large and splendid” Sung city of Xiangyang, he claims to have been instrumental in its capture. Along with his father, uncle, and two foreign engineers, he says, he designed a mangonel, a giant catapult, which lobbed stones into the city so that its defenders were panicked into surrender. Yet this unlikely story is invalidated by chronology: the city’s capitulation took place in January 1273, some two years before Marco Polo even reached China.

Here, it seems, Polo has fallen victim to sheer self-aggrandizement. What, one wonders, did his father and uncle think, who survived to hear this story? Perhaps they were complicit in it. Perhaps he even offered it to them as a sop: for after his arrival in China he barely mentions them again, as if their presence would detract from his own stature. Marco claimed, moreover, to have been for three years governor of the important trading city of Yangzhou. Yet once again there is no mention of him (or any Polo) in the detailed Chinese annals of the time.

Other matters have stirred doubt among critics, such as Polo’s failure to record the Chinese practice of female footbinding, printing, or the presence of the Great Wall. But Polo’s book is the flotsam of memory, with all its gaps and elisions. There were things that may even have become so familiar to him that he lost sight of their strangeness. He does, in fact, obliquely allude to foot-binding; and the Great Wall in his day was not the mountain-cresting spectacle built by the Ming dynasty three centuries later, but a cruder assemblage of staked palisades made of earth or clay. More remarkable is the information Polo gives about phenomena which only became common knowledge years—or centuries—after him. His account of the disastrous Mongol expedition against Japan, however imprecise, was almost the first intimation that another country lay beyond the vast landmass of China. His record of the widespread use of coal and of paper money (first widely circulated under the Sung dynasty) fell strangely on European ears. And alongside rumors of dog-faced cannibals or of the mythic Prester John, other instances of hearsay ring belatedly true. Polo’s descriptions of the custom of couvade, for instance—of men appropriating the power of women in childbirth, by imitation—was received with blank disbelief until confirmed by modern anthropologists.

However incoherently Polo’s outbound journey was remembered and written, the modern traveler on the Silk Road stumbles with sudden recognition on phenomena he recorded. His account of the “Old Man of the Mountain,” founder of the fearsome sect of Assassins, is a garbled memory of a murderous Ismaili sect liquidated by the Mongols. But even today the traveler may ascend to their ruined bastion of Alamut in northwest Iran, and glimpse the cliff-castle of Maimundiz where they met their end.

Advertisement

In the Pamir Mountains the monstrously horned rams that Polo described, now named “Marco Polo sheep,” have become an endangered species; the air on the plateau is indeed so starved of oxygen that “no birds are to be seen near their summits”; and fire, as he records with amazement, burns only fitfully.

His journey along the southern rim of the Taklamakan desert may be followed to the salt wastes of Lop Nur and the shrines of Dunhuang, crowded, as in his day, with “idols”; and the sand dunes are still eerily noisy and shifting—although their sounds are now attributed to sharp temperature changes rather than the bustling of demons. The rare traveler to Khotan may still find the jade pebbles (Polo thought them chalcedony and jasper) carried on its rivers, or stumble with surprise on asbestos (“salamander”) mines in the Altun Mountains: “but of the salamander under the form of a serpent,” Polo writes in one version, “supposed to exist in fire, I could never discover any traces in the eastern regions.” Northward, the town of Hami (Polo’s Chamul) remains rich in fruit, especially melons—but its women no longer consort freely with travelers; and eastward into modern Gansu province, in the obscure town of Zhangye, you may stumble with astonishment on one of the same giant reclining Buddhas that Polo knew.

But the most solid corroboration of Polo’s biography lies in his departure. In 1291, after nearly seventeen years in the service of the great khan, he says, he with his father and uncle joined a naval mission escorting the Mongol princess Cogatin westward. She was the bride promised to the Mongol ruler of Persia, and this apparently secret mission was only confirmed years later, from Chinese and Persian sources.

The marvels that Polo recorded, of course, have gilded his book with an aura of fantasy. Wherever he did not personally observe his subject, he grew credulous. For beyond the horizons of his contemporary world the earth blurred into infinite possibility. More than a generation after Polo’s day, the Travels of Sir John Mandeville, a ragbag of wonders and borrowings—and the most widely read book of its kind—was only falteringly disbelieved. So too, as Polo reaches beyond his immediate knowledge, his stories grow shaky with the fears and rumors of his time: with Tibetan astrologers conjuring tempests and thunderbolts, with the realm of Gog and Magog, and the ruch bird which carries off elephants, then drops them to smash on the ground before eating them. And black magicians effected the most famous miracle of all: the golden cups at the feast of the great khan, which levitated back and forth at his table before the eyes of the whole court.

But in general Marco Polo was hardheaded. His veneration for the emperor may have been steeped in his bedazzlement by power and riches, and the Venetian was vulnerable to Mongol myths about themselves, praising even Chinggis Khan as a paragon of kindly justice. But the esteem in which he held the great khan Khubilai was not misplaced. That ruler, by Polo’s time, had forged the largest and most populous empire there had ever been, and was attempting to unify it with a shrewd and farsighted tolerance.

The assessment of Marco Polo’s character and integrity is complicated by the production of his Description of the World, which soon became known as The Travels of Marco Polo. For the book was not written by Polo, but narrated by him to a writer of Arthurian romances named Rustichello of Pisa while they languished together in a Genoese jail.

It was probably three years after his return from China that Polo financed his own war galley, as was the Venetian custom, and commanded it against Venice’s old sea rival, the republic of Genoa. At the disastrous battle of Curzola in 1298, the Venetians were decimated, and Polo became a privileged captive in the Genoese palace-prison of San Giorgio. Here, in the tedium of a year-long internment, he related his story to his fellow prisoner Rustichello. Theirs was probably not an arduous confinement. Polo, according to his sixteenth-century biographer Giovanni Battista Ramusio, was even able to request his traveling field notes to be sent to him from Venice. Rustichello took his story down in a mangled French—French was the court and literary language for much of contemporary Europe—then disappeared from history.

Within a few years the Description had been translated into Latin and Italian, but here and there Rustichello’s phrases echoing chivalric romance can still be detected, together with some conventional dramatic interpolations and Christian pieties. But it is impossible to know how much the self-glorification in the Description is the work of Polo, his scribe, or subsequent editors.

The proliferating manuscripts of the Description of the World have spawned a scholarly industry. Of some 140 extant, no two are identical. Whole passages defy chronological order. Other chapters seem truncated, as if half lost. There are translations at three or four times remove from any supposed original, and clerical errors have sent up a trail of Chinese whispers. While no definitive manuscript has ever emerged, scholars have diagnosed two main versions among what survives, one perhaps a subsequent elaboration on the other.

Polo himself was released back to Venice in 1299. He was forty-five years old. Almost at once he married a merchant’s daughter and sired three daughters of his own, living with relatives in the Ca’ Polo. It is hard to assess his wealth. But with age he seems to have grown ungenerous—perhaps embittered that his story was not widely believed—and to have engaged in petty litigation for the return of debts, sometimes from members of his own family.

On his deathbed in 1324, distributing his wealth among his immediate kin, he named among his assets a golden tablet conferred on him as a passport by “the magnificent Khan of the Tartars,” and a jeweled Mongol headdress; and he finally released his Tartar servant from slavery. By this time, it seems, although he tirelessly propagated his own story and may even have presented one manuscript to a French nobleman, his Description of the World was still suspect: esteemed by some, doubted by others, and not yet widely read. Urchins, it was said, would follow Polo through the lanes, crying out “Messer Marco, tell us another lie!,” and on his deathbed pious relatives begged him to recant his taller stories.

Other legends gathered about him with time, many recounted by his enthusiastic biographer Ramusio in the mid-sixteenth century. It was said that when the Polos returned to their Venetian home, in dilapidated Tartar robes, their relatives failed to recognize them: they had been presumed dead. The wife of Polo’s uncle, moreover, was so disgusted by her husband’s Mongol coat that she gave it to a passing beggar. Through habit the old merchant had sewn a fortune in jewels into the lining, and only recovered the coat—its gems still in place—by feigning madness on the Rialto bridge and seizing back the garment after the beggar joined the gawping crowds.

A more famous tale concerned the Polos’ failure to convince their relatives of all that they had done. Typically Venetian, they overcame this by a show of wealth. While hosting a lavish party, they suddenly confronted the guests in their Mongol robes, and slit open the hems to loose cascades of jewels. “And when this thing became known throughout Venice,” Ramusio continues,

straightway did the whole city, the gentry as well as the common folk, flock to their house, to embrace them and to shower them with caresses and show demonstrations of affection and reverence….

Yet through the fourteenth century, it seems, Marco Polo’s book was largely disbelieved, or accepted only as pure fable. Even his translators sometimes distanced themselves from its claims. But whatever changes were in the air, this skepticism gradually died. By 1492, when Columbus sailed for the New World, he did so carrying a heavily annotated copy of Polo’s Description of the World, hoping to find China; and by the seventeenth century Polo was recognized at last in his home city as a master explorer.

But by now the world that Polo depicted—the gorgeous, violent pageant of Mongol rule—had utterly vanished. A full thirty years before Marco was buried beside his father under the porch of the church of San Lorenzo (a tomb now vanished), Khubilai Khan had gone to his own grave, wearied with personal loss and the strains of his impossible rule. Soon afterward, the dynasty he founded crumbled away. As the Chinese rose, the Mongol power ebbed back into insignificance. By the mid-fifteenth century Central Asia had broken up into warring states, and China, under its native Ming dynasty, closed up the Great Wall against the Silk Road and—in a grand act of self-occlusion—demasted its entire heavy merchant fleet of 3,500 ships.

Venice, meanwhile, would soon flower into the opulent city-state of Titian and Tintoretto, with a constellation of colonies through the eastern Mediterranean. But at the same time the vigor and enterprise of its old merchant aristocracy was being deflected into the safer business of real estate on the Italian mainland; and the tough, entrepreneurial republic of Polo’s time would soon become a memory.

Yet as Venice declined, the reputation of Polo grew. The phantasmal Eastern empire that he celebrated with such awe and tolerance was slowly retrieved out of oblivion by other travel and scholarship, and Marco Polo became at last his city’s most famous son.

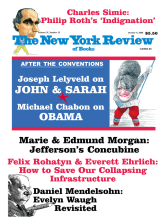

This Issue

October 9, 2008

-

*

This essay will appear, in somewhat different form, as the introduction to a new edition of The Travels of Marco Polo, to be published by Everyman’s Library in November.

↩