1.

Many writers—myself included—owe a great debt to V.S. (“Vidia”) Naipaul. He opened up new literary possibilities, ways of seeing and describing the world, especially the non-Western world. The hardest thing for admirers is to avoid imitating him. To sound like a writer one respects may be a sincere form of flattery, but it is also a profound misunderstanding of what makes Naipaul, or indeed any good writer, extraordinary. Finding his own voice is something of an obsession to which Naipaul returns often in his reflections on writing: the constant search for his place in the world, a unique perspective, a writerly compass.

Naipaul’s voice, which some younger writers are tempted to mimic, cannot be defined by citing his opinions on race, the colonial experience, India, literature, or anything else. His views are frequently designed to shock and outrage, thrown out, especially in interviews, as a kind of smokescreen to protect the autonomy of “the writer.” No, what makes Naipaul’s writing so inspiring is the way he makes an art out of experience, travel, careful scrutiny of the physical world, and sharp analysis of ideas, history, culture, politics.

“Travel writing” of an earlier generation than Naipaul’s—Robert Byron, Evelyn Waugh, Peter Fleming—was often a form of escape, for the author and the reader; escape from dull, gray, philistine England, escape from the strictures of class, sexual mores, and the stifling charms of boarding school education. Foreigners and their peculiar ways were infuriating, to be sure, but also highly amusing.

Naipaul’s books about India, Africa, the Caribbean, Latin America, and Asia, though sometimes comical, are not of this type. Nor are they opportunities for self-display, another staple of the travel genre. Naipaul’s literary discovery of the world is marked by the way he uses his eyes and ears. Impatient with abstractions, he listens to people, not just their views, but the tone of their voices, the telling evasions, the precise choice of words. His eyes, meanwhile, register everything, the clothes, the gestures, the facial expressions, the physical details that allow him to pin people down, like butterflies in the expert hands of a lepidopterist. These observations are filtered through a mind that is alert, never sentimental, and deeply suspicious of romantic cant.

Naipaul’s voice, in fiction and non-fiction, is personal in the sense that he draws his material from his own experiences; his travels, his childhood in Trinidad, his life in England. Yet he has chosen to leave much out. His first wife, Pat Hale, who died in 1996, is never mentioned, even though she accompanied him on trips to India and elsewhere. Nor is Margaret Murray, Naipaul’s Anglo-Argentinian mistress for many years, who was frequently with him when his wife was not. There is no special reason why they should be mentioned. They were not part of the story that the writer wished to tell.

The merit of writers’ biographies continues to be disputed. For some, the work is all we need to know. Others say they love the books, so they want to know more about the people who wrote them. Then there is always the possibility that the life will throw light on the books and deepen our understanding of them. Naipaul himself had this to say:

The lives of writers are a legitimate subject of inquiry; and the truth should not be skimped. It may well be, in fact, that a full account of a writer’s life might in the end be more a work of literature and more illuminating—of a cultural or historical moment—than the writer’s books.

Nonetheless, when I was approached in the early 1990s by Gillon Aitken, Naipaul’s literary agent, with the idea of writing an authorized biography, I was intrigued, flattered, and deeply apprehensive. The idea of writing the life of a man who was still alive was daunting enough. Such projects typically result in acrimony. The idea of writing the life of a man as fastidious and difficult as V.S. Naipaul was particularly daunting. And I was not at all sure that delving into the nooks and crannies of his private life would be a pleasure for me, or enlightening for the readers. I can still remember my sense of embarrassment when Naipaul, looking intently at his shiny brown shoes, began to tell me about his sexual frustrations, as we sat opposite one another in his oddly impersonal London flat. I knew then that this project was not for me.1 I doubted whether an honest book could be written by anyone while Naipaul was still alive.

I was wrong. The truth is not skimped in Patrick French’s excellent book. Naipaul gave his biographer complete access to his papers, including his late wife’s quite depressing correspondence and diaries; he was interviewed at great length, and did not ask for any changes in the manuscript. Not only did he talk to French, but he apparently did so with remarkable candor. The result is almost the invention of a new genre: the confessional biography. And, yes, the sex actually is relevant to the work.

Advertisement

2.

The public image of V.S. Naipaul, distilled from interviews with the writer and anecdotes passed on by people who have met him, is of an angry man, quick to take offense, capable of extraordinary and gratuitous acts of rudeness, obsessed with his status as a great writer, willfully shocking in his views, and incapable of suffering fools, or anyone really, including those nearest to him, gladly. This, by the way, is not the Naipaul I knew. I found him amusing, courteous, even a little diffident. But I could see flashes of the other Naipaul, the man who loves to outrage. The source of this love is one of the fascinating themes running through the biography.

Some people who have felt Naipaul’s verbal lashes see him as a bigot who turned on his own Caribbean background by taking on the worst prejudices of the Indian Brahmin and the British colonial Blimp.2 Although bitterness about the way black politicians in Trinidad went after the Indian minority in the 1950s certainly affected Naipaul’s views of his native island, and his harsh comments on African cultural and political life suggest a less than friendly attitude toward black people, Naipaul is too complex a figure to be dismissed as a racist. For in fact he has written about Africans, as well as Asians, with more intimacy and sympathy than many hand-wringing leftists who take a more abstract view of humanity.

I think French is right to explain (which is not to condone) some of Naipaul’s more provocative views as a form of mischief, which Trinidadians call picong, from the French piquant, a type of sharp talk where, in French’s words, “the boundary between good and bad taste is deliberately blurred, and the listener sent reeling.” French cites the opening of Naipaul’s The Middle Passage as an example. It is a book about the West Indies, its history of massacre and slavery, the self-hatred of the blacks resulting from colonial indignity, the corruption of nationalist politics, the cruelty of race hatred. Naipaul begins by describing his voyage to Trinidad by ship from England, where he had been working for the BBC Caribbean program. He writes:

There was such a crowd of immigrant type West Indians on the boat-train platform at Waterloo that I was glad I was travelling first class to the West-Indies.

His eyes are drawn by “a very tall and ill-made Negro,” whose “grotesque” features he describes with horrified relish.

Naipaul denied that he was setting himself up as superior:

I’m being very mischievous…. I’d be allowed to say things like that among the West Indians who were doing that Caribbean programme. We made those kind of jokes. I wasn’t aware that an English reader might worry about where I was positioning myself.

Maybe. But it is true, contrary to his reputation, that Naipaul is just as capable of directing his picong toward the English themselves. French quotes from an interview he gave in 1980: “In England people are very proud of being very stupid. A great price is being paid here for the cult of stupidity and idleness…. Living here has been a kind of castration, really.”

V.S. Naipaul as a Trinidadian trickster, playing the fool while getting others to pick up his expensive bills, having his fun by enraging Western liberals with opinions that mimic the prejudices of the old colonial masters: it is an interesting and I think plausible take on the public figure. Commenting on Sir Vidia’s Shadow (1998), Paul Theroux’s rather bitter memoir of his former friend and idol,3 Lloyd Best, Naipaul’s old schoolmate, remarked:

All these little Trinidadian smart-man things: the way he would sing calypso and whistle, the way he would take the mickey out of people, provoking them. Naipaul expects the responses that he’s going to get; I’d say that it’s second nature to him, performing in that way.

In his books, however, Naipaul is less frivolous. His rages at shoddy towels in hotel bathrooms, the trivial shenanigans of third-world taxi drivers, or the incompetence of the kitchen staff in some tropical hotel might sometimes be played to comic effect. But more often they are honest reflections of his own “raw nerves,” of the man who is desperate to throw off the humiliations of colonial society while not feeling entirely at ease in the metropolitan world in which he has made his home.

Like many writers of fiction or nonfiction, Naipaul has created himself as a character, a semimythical figure expressive of deeper concerns than the desire to shock. He is portrayed as a young man who escaped the provinciality of a small Caribbean island only to feel the sting of racial and colonial prejudice in England, as a writer who sees great achievement as the only way to shake off colonial indignity, as a man who seeks to express the truth about societies so ravaged by violence and degradation that their people can only find refuge in lies. The great merit of a superb biography, such as this one, is that it can deepen our understanding of the literary character by telling us more about its creator.

Advertisement

Naipaul grew up in a society built on fictions, a place where family names were often made up, where people pretended to be all kinds of things, few of them true. Again French quotes Lloyd Best, a black Trinidadian who attended Queen’s Royal College, a British-style school with high academic standards, at the same time as Naipaul (C.L.R. James was another alumnus):

The most important single feature of Trinidadian culture is the extent to which masks are indispensable, because there are so many different cultures and ethnicities in this country that people have to play a vast multiplicity of roles, each of which has got its own mask depending on where they are.

Naipaul cannot even be sure of his family name. There are doubts, too, about the Brahminical caste status to which his family lays claim, especially the maternal side of his family, which felt superior to his father’s. Masquerading has been a feature of Naipaul’s work, from the early comic novels, Miguel Street and The Mimic Men, to his later literary journeys through Asia, Africa, and Latin America. In his own life, he personifies the trickster—the theatrical Oxford drawl, the shocking statements, the Blimpish behavior—but he is at the same time hypersensitive to any form of fraudulence, which he associates not only with colonial society but, it seems, with all human relations. “It is important not to trust people too much,” he told his biographer. “Friendship might be turned against you in a foolish way…. I profoundly feel that people are letting you down all the time.”

Even as a child, Naipaul wanted to distinguish himself from his fellows as someone special. He was afraid of being held back, imprisoned by his surroundings: the squalor of communal life in a small family house in Port of Spain, the torpid parochialism of Trinidad. At school, he later declared, “I had only admirers; I had no friends.” In fact, this was an exaggeration. It is the way he chooses to remember his early life, as a man apart, unassailable. But he was convinced, early on, that to advance in the world and find his rightful place in it, he had to leave. A scholarship to study at Oxford allowed him to do so.

Tormented by a feeling of sexual inadequacy, and being a colonial misfit, he was miserable for most of his time at Oxford. But there was no turning back. An encounter with a fellow old boy of his Trinidad school left him in a peculiar fury: “I never realised the man was so utterly ugly, so utterly coarse—low forehead, square, fat face, thick lips, wavy hair combed straight back.” What’s more, the man wore the wrong kind of blazer: “Wearing the blazer of a Caroni Cricket Club in Oxford. I ask you—can you conceive anything narrower and stupider?” This sounds like the opening of A Middle Passage. French, I think, gets it right:

This disproportionate rage, though, was provoked by ideas as well as by appearance; Vidia’s rage against these individuals arose in part from his view of the world, and a conviction that his own future lay at the centre, not the periphery.

The passionate urge to be different, to be unassailable, beyond the reach of colonial fraudulence and metropolitan disdain,4 resulted in Naipaul’s invention of himself as “the writer,” the great observer, the unflinching teller of truth. The role of the women in his life, his wife Pat first and foremost, was to support him in that role with complete devotion. When both were still in their twenties, Naipaul wrote to Pat—whom he’d met when they were at Oxford—that he was a spectator with no desire to reform the human race, a man without loyalties, interested in nothing but writing the truth as he saw it. French takes him at his word:

Contrary to the depredations that would be launched against Vidia with increasing force over the coming decades, his moral axis was not white European culture, or pre-Islamic Hindu culture, or any other passing culture: it was internal, it was himself.

I think this is right. The question is whether such a personal moral axis can distort the truth as much as a more culturally centered perspective. This is where the biography is most illuminating, and where the sexual life comes in.

3.

Naipaul’s first sexual experience was, it seems, unwelcome. He was seduced by his older cousin Boysie in the tight sleeping quarters of the extended family. As Naipaul remembers it: “I was corrupted, I was assaulted. I was about six or seven. It was done in a sly, terrible way and it gave me a hatred, a detestation of this homosexual thing.” Perhaps so, but the “assaults” continued for two or three years. And French remarks that Naipaul always describes men in his writing in greater physical detail than women. When he wrote an article about David Hockney in the early 1970s, Naipaul was excited by what French calls “the proximity of sex, and an awareness that he was himself attractive to gay men.”

This is not to say that Naipaul is really a repressed homosexual, but rather that the line between disgust and lust seems to have been a very thin one. Naipaul himself has often talked about his frequent relations with prostitutes. This habit, kept up for many years, in London, Amsterdam, and Spain, among other places, is usually ascribed by Naipaul to the unsatisfactory nature of his marital relations with Pat, who was, if anything, even more inhibited and awkward about sex than her husband. But in fact, as French tells us, Naipaul’s

interest in women who would do imaginable sexual things for money dated back to his teenage days in Port of Spain. Seduction would not be involved; nor was the woman required to dissemble. A woman who sold herself to a man for sex embodied his internal collision between repulsion and desire.

In a way, then, this too was a matter of truth.

In 1963, after several years of active brothel-visiting, Naipaul commented on the case of Jack Profumo, the British secretary of state for war, who was forced to resign after it was revealed that he had frequented the same prostitute as a Russian naval attaché in London. “I have never met a man who has been with a prostitute,” Naipaul declared. “I have met few who have not professed horror at the thought…. Prostitutes are outlaws, necessary to some and denied by all. They are little known and greatly feared.”

This was clearly not entirely truthful. Still, to feel shame about one’s deepest compulsions is a common human trait, as is the need to cover it up. This, in itself, does not make Naipaul special. The issue is how the sex life affected his work.

Less than ten years after the Profumo affair, Naipaul flew to Buenos Aires to write an article for The New York Review. He had just spent some time in Trinidad, attending a sensational murder trial. Followers of Michael X, a sinister revolutionary figure briefly lionized in fashionable London, had hacked an English girl to death with a machete. The daughter of a Tory MP, she had been the besotted slave of a powerful thug named Hakim Jamal, who had also had some kind of relationship in London with Naipaul’s then editor, Diana Athill. This case of sexual slavery, revolutionary posturing, and black brutality fascinated Naipaul, and would result in a brilliant article, as well as a novel, entitled Guerrillas.

In Buenos Aires, at the apartment of Borges’s translator, Naipaul met Margaret Murray, a vivacious Anglo-Argentinian:

I wished to possess her as soon as I saw her…. I loved her eyes. I loved her mouth. I loved everything about her and I have never stopped loving her, actually. What a panic it was for me to win her because I had no seducing talent at all. And somehow the need was so great that I did do it.

Margaret left her husband and children, and for the next twenty years would be at the beck and call of her master, who was finally able to do all the things that had horrified and fascinated him before. French gives us some idea about their taste for sadomasochism. The more Naipaul abused Margaret, the more she came back for more. She wrote him letters, paraphrased by French, about worshiping at the shrine of the master’s penis, about “Vido” as a horrible black man with hideous powers over her. Her letters were often left unopened, and certainly unanswered, adding to her sense of submission. According to Naipaul, he beat her so severely on one occasion that his hand hurt, and her face was so badly disfigured that she couldn’t appear in public (the hurt hand seems to have been of greater concern). But Naipaul said, “She didn’t mind at all. She thought of it in terms of my passion for her.” And then there was the mutual passion for anal sex, or as Margaret put it (paraphrased by French), “visiting the very special place of love.”

Meeting Margaret made Naipaul feel sexually happy for the first time in his life. A heavy price was paid, notably by Pat, back in England, whom Naipaul felt unable to leave and treated as a kind of slavish mother figure; she continued to take care of all his needs, bore his endless verbal abuse, read his manuscripts, and listened to his confessions about Margaret. As Naipaul mused, much later, after Pat had died of cancer: “I was liberated. She was destroyed. It was inevitable.”

What is striking is the somewhat extreme nature of Naipaul’s selfishness. News of Margaret’s pregnancies, the result of her encounters with the master, either fell on deaf ears or were met with accusations of blackmail, or with the idea that the baby might be raised in England by Pat. In any event, no baby was born. Naipaul the writer, however, was affected as well as the private person. He began to write explicitly about sex, especially violent sex, involving sodomy. His books, he remarked, “stopped being dry after Margaret, and it was a great liberation.” Dry they were not, but there is room for doubt about the liberation.

Guerrillas is a fictional version of the Trinidad murder case about which Naipaul first wrote a long article. Both the article and the novel describe the sexual enslavement of the English girl by a black revolutionary in terms that bear a remarkable resemblance to Naipaul’s own relationship with Margaret. French writes that Margaret told her lover that she could feel her own presence in the article. But the male dominance, the female submission to a black man, the violence, the anal sex, are described with a kind of passionate loathing that does not read like the tone of a liberated man. Naipaul’s editor, Diana Athill, remarked that Naipaul misrepresented the English girl in the story. She was not a typical middle-class girl in expensive clothes who idolized masculine negritude, but an ill-nourished, disturbed young woman who would have gone “for anyone sexy who offered her a cult, even if he’d been as white as milk.” Athill concluded that Nai- paul had distorted the truth to make a point about middle-class white girls; she told him, “you are cutting your cloth to fit your pattern, and that’s unlike you.”

Well, maybe not entirely unlike him. In 1962, Naipaul set off for India for the first time, with Pat, to write a book he had long planned, “about these damned people and the wretched country of theirs, exposing their detestable traits.” He wrote this to his elder sister, Kamla, possibly in his Trinidadian trickster mode. The book that came out of it, An Area of Darkness, is brilliant reportage. But there are signs that he did not always avoid cutting the cloth to fit his preconceived patterns.

Naipaul describes how, on his arrival in Bombay, he was approached by a “thin and shabby” Indian travel agent, who asked him for “cheej.” Naipaul imagines that the man wanted cheese, a request that he saw as typical of the primitive state of India: “Imports were restricted, and the Indians had not yet learned how to make cheese, just as they had not yet learned how to bleach newsprint.” It took Pat, who had learned some Hindi, to figure out that “cheej” or “cheez” actually meant “stuff,” and could have referred to any kind of contraband.

A small lapse, but a telling one. More interesting is Naipaul’s old habit of slipping between lust and rage. After the publication of Guerrillas, which Joe Klein, reviewing the book in Mother Jones, said could “best be described as a literature of buggery: his main purpose seems to be the desecration of his audience,” Naipaul wrote an evocative article about Argentina for The New York Review. Entitled “The Brothels Behind the Graveyard,” the essay explains the corrupt and brutal nature of Argentina’s politics through the image of brothels in Buenos Aires, near the funerary monuments at Recoleta. Every schoolgirl, Naipaul writes, knows that she may end up there, “among the colored lights and mirrors,” for this is “a society still ruled by degenerate machismo, which decrees that a woman’s place is essentially in the brothel.” Not just that, but they will be subjected to that typical act of Argentinian male brutishness, anal penetration: “The act of straight sex, easily bought, is of no great moment to the macho. His conquest of a woman is complete only when he has buggered her.”

At the time, the Argentinians were not pleased with this analysis, which does not mean that Naipaul was wrong. Perhaps his own predilections had sharpened his sensitivity to something in the atmosphere of Argentina under the dictators. Yet one can’t help feeling that the article, beautifully and passionately written, tells us at least as much about the author as about his subject.

4.

All this—the relationship with Margaret, Pat’s desolation, Naipaul’s rages, as well as his great spurts of creative work—is well described by Patrick French. It is not his fault that the last part of the book is less revelatory, at least to this reader. More good books, including the masterpieces, A Bend in the River, The Enigma of Arrival, and (a favorite of mine) Finding the Center, were still to come in the last two decades of the twentieth century. Travel, politics, history, and reflections on his art and life blended perfectly in these books. But in his personal life, as often happens when people get older, some of the old trickster’s masks began to harden on the face. Accounts of bad boy behavior, often in the form of outlandish financial demands, encouraged by a fawning entourage of agents and admirers, make dispiriting reading. The rudeness becomes less amusing, more tiresome. And the egotism is downright depressing.

After years of waiting for phone calls, which came when it suited her on-and-off lover, or letters, which rarely came at all, Margaret was eventually dumped after Naipaul ran into the last of his devoted women. Nadira Khannum Alvi, a Pakistani journalist and divorced mother of two, spotted Naipaul at a party in Lahore in October 1995, and asked if she could kiss him as “a tribute to you, a tribute to you.” Pat, at that time, was dying of cancer in England. Before setting off on his Asian journey, to Indonesia and Pakistan, Naipaul had arranged, with his accountant, for her letters and diaries to be shipped to his archive at the University of Tulsa on her death.

Back in England, as Pat lay on her deathbed, Naipaul read his Indonesia notes to her. She died in February 1996. In April he married Nadira in Salisbury, in the presence of his agent, Gillon Aitken, a few relatives, a German diplomat and his wife, whom Nadira knew, and myself, as his then still prospective biographer. Later, at his Wiltshire cottage, after he served us white wine, whose fineness he vouched for, he shocked the German diplomat’s wife, who had just been praising Pakistani culture, by murmuring “barbarism, barbarism,” and spoke to me about Pat’s devotion to his work. It was altogether a most peculiar occasion. Margaret learned of the marriage only afterward, by reading about it in the newspapers. Naipaul said nothing, but dispatched Gillon Aitken to Buenos Aires with a checkbook.

A sad waning then of a brilliant writer’s life. Except that it is not yet over. Naipaul continues to write books, some of them too thin, some too long, but still, at their best, redeemed not only by his lucid prose but with a quality that graces the work of a supreme egotist: the willingness and ability to listen. Not many distinguished Nobel laureates would be prepared to travel to remote parts of Pakistan or the Congo (his latest venture) to hear the stories of unknown people. Naipaul is. And this is a sign of great modesty, for in the lives of the humblest Indonesian, the most undistinguished Pakistani, or the poorest African, he is still able to see traces of his own.

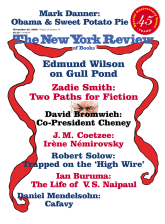

This Issue

November 20, 2008

The Co-President at Work

At Gull Pond

Two Paths for the Novel

-

1

This is not quite the way Patrick French relates the story of my brief involvement. Which just goes to show how the same events can leave different memories.

↩ -

2

Derek Walcott’s take on Naipaul would be an example of this. Naipaul was an early admirer of his fellow Nobel laureate, but later expressed less obliging opinions of his work. The feeling appears to be mutual.

↩ -

3

Sir Vidia’s Shadow (Houghton Mifflin, 1998).

↩ -

4

This was often real enough. Evelyn Waugh once referred to Naipaul as “that clever little nigger,” and when Naipaul applied as a feature writer to the BBC, the members of the interview panel just laughed.

↩