About two thirds of the way through Cave, City, and Eagle’s Nest, a new book of descriptions and interpretations of a sixteenth-century indigenous painting from central Mexico, the historian of religion Vincent James Stanzione describes at some length a four-day voyage of initiation in the mid-1990s, on which he accompanied twenty-two young Maya men from their highland community on the beautiful shores of Lake Atitlán, Guatemala, to the lush lowlands and back again. All along the way, he reports, the pilgrims stopped for prayer, reflection, and ceremonial drinking at the very same spots where their fathers and forefathers before them had prayed and offered sacrifices.

The young men, who were members of a cofradía— traditional organizations that are linked to the Catholic Church but are devoted to a community’s own religious practice—started their trip with empty carrying frames strapped on their backs. On their arrival in the tropics they stole into lowland orchards to stage a symbolic hunt for fruit. Now pregnant, as Stanzione puts it, with their bounty, they began the punishing hike back to Santiago Atitlán. At the entrance to the village, as some of them cried with exhaustion and relief, they were welcomed by their young brides, whom they would be able to lie with now that they were men, able to offer the gift of their own fertility, as embodied in the fruit.

It is a beautiful story, beautifully told, but should any reader feel inspired by it to travel to a Maya community in order to serve an apprenticeship there in the deep ceremonies of life, Stanzione warns:

Now that paved highways have been built [from Atitlán to the tropics], now that most of the town’s residents are Evangelical Protestants, now that the cofradía system is all but dead, now that marriage is not as important to the people of Santiago as it once was, this “costumbre” or ritual of bringing home the fruit is no longer performed.1

Stanzione, who arrived in Santiago Atitlán some twenty years ago and has lived there since, is fortunate to have been present for the last enactments of a ritual strongly rooted in the preHispanic past, for it is precisely in the decades that he has been in Guatemala that, after centuries of existence, the cofradía system has finally collapsed. It embodied a vision of the order and place of things and humans in the world, with such strong roots in the pre-Hispanic past that epigraphers, like the groundbreaking Linda Shele, have been able to use Maya communities’ rituals and daily practice to decipher pictograms carved in stone a thousand years ago.

The drastically increased rate of change is being felt not only in Guatemala: the religious vision, languages, dress, forms of production, daily round of duties, and network of obligations that bound together the Tzeltal, Otomí, Guaraní, Araucano, Inuit, Arhuaco, Ianomame, Ayoreo, Rarámuri, Kolla, Navajo, Arara, and Ojibway, to name a few, have been losing ground like the ice on the North Pole. Soon our only access to Amerindian modes of thought—and, too, Amerindians’ only access to a record of their thought, their own recording of their history—may be through artifacts and accounts belonging to the past. We can be sure that few accounts will be more expressive and intriguing than the Mapa de Cuauhtinchan No. 2.

The mapa, a breathtaking tableau roughly 1 x 2 yards in size, was painted on the beaten bark of the native amate, or mulberry tree. It was created by painters who spoke the Nahuatl language from the nation-state of Cuauhtinchan—Eagle’s Nest—in the decades immediately following the conquest of Mexico. Many post-Conquest maps were used by Indian communities to affirm their land rights before colonial authorities. Because much of the subject matter of the Mapa de Cuauhtinchan No. 2 is unusual for this genre, we do not know this painting’s original purpose; in fact, even what one half of the mapa is a depiction of (a pilgrimage? municipal limits? a spiritual journey?) is a matter of intense discussion in several of the fifteen essays that make up Cave, City, and Eagle’s Nest. But the artists’ accomplishment is to have provided a thrilling, exquisite, and mysterious register of their spiritual universe as it was before conquest broke it apart.

1.

In the late 1990s Ángeles Espinosa Yglesias, the extremely rich daughter of the Mexican banker Manuel Espinosa Yglesias,2 bought one of the few hundred surviving paintings produced in Mexico in the half-century following the Conquest. The painting that Espinosa Yglesias acquired from the private collection of a Mexico City family was richly detailed, but it was so damaged by moisture, rot, and vermin that large parts of it were impossible to read.

Nevertheless, it was clearly a drawing of a place and, the painting stated in careful Latin letters, it referred to the now vanished community or city-state of Cuauhtinchan (“Place of the Eagle’s Nest”).3 Paths could be seen in the painting, represented by a trail of delicate footprints. Human beings, chichimecas—which means “barbarians”—bustled up and down the length of the map dressed in animal skins. Frequently, they appeared in the company of far more civilized men dressed regally in tilmas—one-shoulder cotton cloaks. There were dreadful scenes of human sacrifice—which a document destined for the eyes of a colonial authority might reasonably have avoided—and, oddly, a scene representing the ritual decapitation of a butterfly, a grasshopper, and a snake. Personified mountains were depicted, with devilish heads where their summits would be. There were naked men—perplexed-looking naked men—turned topsy-turvy by a whirlwind, and also a flying goddess leading warriors out of a cave.

Advertisement

“Its beauty literally stunned me,” Espinosa Yglesias wrote of the mapa a few months before she died last year. Thinking that the information locked in its images should be decoded, she asked John Coatsworth, who was at the time the director of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies at Harvard, for help. In addition, she commissioned restoration work on the painting from the Mexican conservator Marina Straulino, who, using state-of-the-art imaging techniques, made visible many sections of the painting no longer accessible to the naked eye. Straulino also created a digital version of the newly legible map.

Meanwhile, Coatsworth turned to Davíd Carrasco, a historian of religion who is the head of the Moses Mesoamerican Archive at Harvard. Carrasco put together a team of scholars of history, anthropology, ethnobotany, and archaeology, among other disciplines, and included in the group the estimable Keiko Yoneda, who has spent decades studying and identifying each figure in an early reproduction of the painting. The team met once in Mexico to examine the document, and a second time at Harvard. The result is the magnificent volume Cave, City, and Eagle’s Nest, which, in addition to the fifteen essays, contains copious illustrations, a poster-size image of the mapa itself, and life-size fold-out reproductions of each of sixteen portions of the whole (see the illustration of Section P on page 63).

How do we know that a person is Indian? How does that person know him- or herself to be Indian? Some academics argue that there is no such thing as a common Indian heritage throughout the Americas; others point out that in most of these countries a great many people are native Americans, genetically speaking, even if they dress like punksters or in business suits. Liberals in the nineteenth century, including the Indian president of Mexico, Benito Juárez, equated cultural Indianness with backwardness, while an all-too-modern world treasures the idea of museum-quality Indians who will remain forever untouched by time, greed, or mall culture. Regardless of the arguments for or against Indianness, it might be generally agreed that a culturally distinct Amerindian will have inherited significant elements of a view of the world that antecedes the Conquest and the arrival of Catholicism. It seems clear, as well, that many of the surviving elements found in different ethnic groups and cultures throughout the hemisphere coincide tantalizingly with each other—enough to be seen as distinguishing characteristics.

One such element is the notion of a world in which all living beings have animal and/or spirit counterparts endowed with magical powers. These beings, and the universe they occupy, can be seen with our own eyes, provided we know how to read the signs. Frequently, a reader of the signs will have recourse to fasting, dance, or hallucinogens to reveal the parallel universe. This shaman, most often a man, is frequently titled the Speaker, and what he speaks when he is in a trance are messages from the parallel world, as well as the history of the tribe and its heroes, all of which form the chain of continuity that holds the community together—a community that includes both its present members and the ancestors who created it.

It would appear that on the left-hand side of the painting the Mapa de Cuauhtinchan No. 2 describes the story of the ancestors’ journey to establish the community, and, on the opposite half, the physical and magical borders of the Cuauhtinchan state they founded. Thus, the mapa would be not so much a map as an epic narrative, an evocation of the barbarian ancestors and of the divine beings who guided them on their journey: first, out of the primal cave of Chicomoztoc, from which the Nahuatl-speaking people believed that human beings emerged; then, through the holy city of Cholula, where they would become civilized (and perhaps learn to sacrifice butterflies and snakes instead of people), and finally on to the sacred Nest of Eagles, where they would stake their claim.

Advertisement

In the closing essay, the book’s two editors, Davíd Carrasco and Scott Sessions, point out the importance of the city that occupies a central space on the map—the sacred center of Cholula—as a “changing place”: a place where identities are transformed. They describe the circuitous path traced on the left-hand side of the painting as a ritual labyrinth of a type common both to initiatory ceremonies and to voyages of discovery. Vincent James Stanzione, evoking the four-day pilgrimage from Lake Atitlán that he participated in, argues that the right-hand side of the mapa could well be a real map—a guide for pilgrims who traverse every year a ritual path in the real world. The left-hand side recreates the initial voyage that the ancestors make over and over again in the parallel word.

The Cuauhtinchan of today is a small town in central Mexico of some eight thousand people, not far from the city of Puebla’s atrocious industrial belt. The lovely colonial cities of Tlaxcala and Cholula are also near, and, visible behind them, the snow-capped volcanos Popocatépetl and Iztacíhuatl. It is a highland region whose fertile plains, pine forests, and spiky vegetation are depicted in the mapa and described with close attention by the modern ethnobotanists whose essays are included in the book.

We know from a sixteenth-century written history from the same area, which was guarded for centuries by the people of Cuauhtinchan, that in the twelfth century the Toltec people of Cholula fought a rival ethnic group for control of the city. Under siege, they looked for assistance. The mapa’s narrative starts in the center of the painting, in Cholula, where two shaman-lords of the besieged Toltecs set out for the barbarian regions of the North, looking for military assistance from the fierce Chichimecas, who are renowned for their skill with bow and arrow.

In the upper left-hand corner we see the beginning of the epic journey of the Chichimeca ancestors of the Cuauhtinchan people from their northern lands to Cholula. A warrior goddess carrying a human trophy-leg flies out of a primal spirit-cave, a mythical spot generally known in the Nahuatl-speaking world as Chicomoztoc. It is depicted in the mapa in traditional style, as a womblike mountain with seven inner hollows. Chichimeca warriors equipped with bows and arrows follow the goddess. The lords from the embattled city of Cholula wait outside, ready to lead the savage Chichimecas to the city. The mapa’s left-hand narrative is limited to this journey from Chicomoztoc to Cholula, and what is striking is that, unlike most such epics, there are no battle scenes or images of conquest and triumph, or mourning and loss. Instead what we see most frequently are the rituals performed at stops for prayer along the way.

2.

For many years I put up a Day of the Dead altar every November 1 in my Mexico City apartment. I did this in collaboration with the woman who used to take care of it and me; Señora Jacinta Cruz Ilescas, a Zapotec woman from a village in highland Oaxaca where traditional dress has long disappeared and only Spanish is now spoken. In a fever of creative ambition, we would find new ways each year to suspend cloth backdrops on a bare wall. We would pin paper cutouts to the cloth; wrap and stack shoeboxes to create small free-standing altars on the larger one; surround portraits of the departed with fruits and the fruit with flowers and small plates of the favorite traditional foods of the deceased. Then we would fit a dozen prayer candles among the dense display of offerings and try to make the whole thing fireproof.

Finally, after we had admired the result and pointed out the current altar’s virtues with regard to the previous year’s, Señora Jacinta would invariably say, “Ah, señora, but if we were in my pueblo, we would be able to uproot a vine chock-full of jicamas, and make an arch for the altar with it. That way it would be right.” Years ago, I read that the Maya people of southern Mexico also make a ceremonial arch from jicama vines, and they still remember why. The radish-like jicamas, which hang down from the vines, and have brown skins but are white on the inside, represent the stars of the Milky Way.

One year, a few weeks before the Day of the Dead, I fretted that I would have to be abroad for that hospitable feast, but Señora Jacinta reassured me: she would prepare my mother’s favorite foods and place them on her own altar—“It’s a good thing she liked her mole Oaxaca-style,” the Oaxacan Jacinta noted—and my mother would no doubt know to arrive at her door rather than mine. “She knows she will be very welcome there,” the señora said calmly, even though the two had never met.

The all-important Day of the Dead festivities in La Paz, the capital of Bolivia, coincide with the week in November during which the sun at the equinox is most directly overhead. This means that at high noon on those days, and particularly on November 8, human beings walking about under the stark blue bowl of the sky cast no shadow. Throughout the world people without shadows have been identified, often spookily, with the dead, but this association is seen as a great opportunity by the urban Aymara and Quechua who make up a large part of the population of La Paz. On the day of no shadows they pack the cemeteries, and they bring with them their ñatitas, or household skulls. These skulls have been procured on the sly from a potter’s field, or the forensic institute, or the family grave—some questions are better left unasked—and they are household helpers. (I heard from a celebrant that if a house is empty and robbers try to break in, for example, the ñatita will turn on all the lights and make it sound as if a blowout party were going on inside.)

On their day of days, the ñatitas are reunited with their fellow dead, and feasted and thanked. Mariachis and native huayno groups and guitar trios serenade them, while their owners, dressed in their most impressive finery (and the amount of gold a prosperous Aymara woman can display is very impressive indeed), prop coca leaves or lit cigarettes between the skulls’ teeth, crown them with flower wreaths, and shower them with petals, make them a present of, say, a brand-new pair of Ray-Ban sunglasses, or a leather motorcycle cap, and then drink to their health.

Traveling this path of ritual through the recurring time of the calendar year—feeding the ancestors, blessing the animals, asking for blessings from the river and stream forces, keeping an infant all but immobile until its soul has had time to catch up with its body—Amerindian peoples have kept themselves whole even as the world has whirled uncontrollably around them, and indeed even as their rural communities have broken up, sending their members into the great diaspora of the cities and far abroad. (There are living in the United States today a not insignificant number of migrants from Chiapas, Oaxaca, and Puebla who speak Maya, Mixtec, Zapotec, and some English, but no Spanish.) For centuries Indian community struggles centered on the right to the land taken from them. In these days of exodus, they fight, in ways that are often confused and contradictory but determined, for their ritual life.

One day in 1993, while waiting in line in a government office in Bogotá, I struck up a conversation with a group of beautiful, cinnamon-skinned men dressed immaculately in flowing white robes. They said they were Arhuacos from the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta—a snow-capped range on the Colombian Caribbean—and they invited me to visit their home.

The drug traders who have murdered so many of the Arhuaco leaders seemed to be in retreat at the time, and it was possible to make one’s way up to the communities without danger. I stayed a couple of days in a peaceable village of perhaps two hundred people, in the midst of orange groves and cornfields, and the inhabitants explained the cultural projects they were trying to get off the ground—a community library, a radio station, and a historical archive of some sort that would be a depository of their history and self-knowledge.

The Arhuacos suffer greatly because mestizo land invaders, illegal loggers, drug traffickers, and government officials have deprived them of their ancestral land—not only their farmland, but the land on which are located the sacred places to which they must make a pilgrimage every year. The attrition caused by religious conversion, forced exodus, and recruitment by coca and marijuana growers has been great, but lately the Arhuaco population has been growing (they number around 50,000). The Arhuacos are extraordinarily skilled and imaginative bureaucratic infighters; they are able to move in and out of the modern world more easily than many other Amerindians. They send their children out into the world to study things like computer programming and medicine, and it would seem that, like the young man who was my self-appointed guide for the visit, at least a few have actually chosen to return, their sense of community and self intact.

On my last night in the Sierra the villagers gathered at a cluster of boulders a short way beyond the last of the rectangular thatched houses. There was no moon and the stars were huge and near. Not wanting to intrude, I hung around the edges of the meeting and listened as a man’s high voice beautifully recounted an epic involving the voyage the stars had once made to be in the company of humans. Then my guide escorted me back to the guest room in the village school.

The following morning I asked to be introduced to the wonderful speaker who had told this tale, and found myself shaking hands with a tiny, grinning man with an easy giggle whom I had earlier taken to be the village fool. He had not told his story in Spanish for the simple reason that he did not speak the language. My hosts could not be convinced that there was something remarkable about the fact that I had thought I was listening in Spanish, nor is it clear to me that the narrative I thought I had heard was in fact related to what the giggling shaman actually said that night, although they seemed to think so, or else didn’t find the question relevant. They walked me to the road and waved goodbye as I climbed into the back of a pickup truck, suddenly and inexplicably in tears. Years later it was a wonderful surprise to learn that despite the continued killings and other offenses against them, many of the projects my Arhuaco hosts had been putting together—a historical archive, their own videos and publications—were being carried out.4

3.

On the first day of 1994, many, if not most, of the Tzotzil and Tzeltal Maya Indian communities of the central Chiapas highlands in southern Mexico staged an uprising against the cabrón gobierno, the son-of-a-bitch government. The fighting, such as it was, took place mainly in the town of Ocosingo and in the vicinity of the charming former state capital, San Cristóbal de las Casas. Then it stopped on the twelfth day, when Mexican president Carlos Salinas de Gortari called a unilateral cease-fire. It had, in any event, been a completely chaotic and ineffective war, which was not altogether surprising once it was learned that the rebels’ improvised training was provided by Subcomandante Marcos, a white-skinned revolutionary with no fighting experience himself who also wrote the Zapatistas’ (much more successful) communiqués.

It was clear, though, that the couple of thousand insurgents, in their homemade uniforms and with hopelessly inadequate weapons—some machine guns, lots of old hunting rifles, and quite a few carved wooden representations of rifles as well—thought that they had a serious chance of victory. Many reporters were struck by the wooden rifles, instruments that seemed somehow linked with the fighters’ idea of the power that oppressed them. “Let the cabrón gobierno leave his palace and come and sit here among us!” the rebels who spoke some Spanish used to say, and it was hard not to think of the Mexicas at the time of the Conquest, putting on their most magically power-filled masks to do battle with the Spaniards, who had guns.

Some of the ski-masked fighters who appeared in the background of interviews with Subcomandante Marcos were quite possibly among the slight, quiet men who before, during, and after the heyday of the uprising slipped into San Cristóbal every market day and spent hours squeezed together on the sidewalk in front of the electronic goods store, watching the silent images of a telenovela flicker on the television screens in the display window. The question arose then, as the rebels in the villages struggled to express their conflicted longings both for a return to tradition and for computers, for unthreatened comunitas and for higher education for their children, of what a good definition of a future for the Amerindian communities might be. Is it possible to be Indian and be modern? Or, rather, is it possible to enjoy the benefits of modern technology and survive an omnipresent market capitalism without destroying an inner life full of meaning, and of meanings?

This May a sequence of aerial photographs taken by employees of Brazil’s indigenous peoples’ protection agency—the Fundação Nacional do Índio, or FUNAI—was broadcast throughout the world. The images showed a clearing where members of a last, uncontacted, tribe of Amerindians live. In the past twenty years or so aerial photography has helped upend the general conception that the Amazon has always been sparsely populated by hunter-gatherers. Along the Amazon river and its tributaries, neatly ordered dwelling-mounds, built above the seasonal flood-line, indicate that the Amazon was actually quite densely populated before the arrival of Europeans and their devastating epidemics, and not by Stone Age nomads but by highly inventive farmers who lived in villages and towns like their fellow Indians in Mesoamerica and the Andes.5

Today, though, the last of the native tribes that live in the Amazon basin—numbering perhaps one thousand people in all—are largely hunter-gatherers. Their habitat is shrinking at an alarming rate, and the past twenty years have seen an exodus of tribes like the Ayoreo, whose last malnourished dwellers in the wild reluctantly made their first contact with the modern world only in 2002. They reported that they were being attacked by jaguars even as they slept by the bonfire in their malocas, no doubt because the big cats were themselves being starved out of their environment.

The people in the aerial photographs taken in May don’t seem malnourished, but they do look very scared of the enormous roaring object—a helicopter—flying above their heads.6 Painted from head to toe in red and black and making ferocious faces, they brandish their strung bows and spears at the horrifying intruder. José Carlos Meirelles of the FUNAI explained that the agency decided to take the photographs in order to prove the existence of isolated tribes, because loggers and farmers and miners often deny that there are such tribes even as they tear down their environment.

How much the images will actually protect these last of the First Peoples is much in doubt. At some point they will most likely be forced to join the rest of their brethren in the reservations and rough, dusty frontier towns on the jungle’s edge, where they might whittle arrows for tourists, or prostitute themselves in exchange for a few coins, and give up on the struggle to make sense of their nightmare new world.

For the moment, though, the roaring flying thing has come and gone, and perhaps the fear it provoked is fading, turning into stories the shaman will tell over and over again by the fire. Perhaps the hallucinogenic leaves of the yahé vine will reveal the apparition’s real meaning to him, or to another seer who will be moved to paint what he has learned on a soaked and flattened strip of bark, one that might endure and be treasured for centuries, like the mapa from Cuauhtinchan.

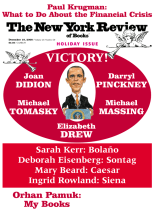

This Issue

December 18, 2008

-

1

Stanzione describes this voyage at greater length in his book Rituals of Sacrifice (University of New Mexico Press, 2003).

↩ -

2

He owned the Banco Nacional de México until its nationalization in 1982 by President José López Portillo.

↩ -

3

There are five from Cuauhtinchan, number two being vastly superior in artistic value.

↩ -

4

Several videos co-produced by Arhuaco and mestizo organizations can be found on the Web. See, for example, “Sierra Nevada: Indigenous Territories and Sacred Sites” at www.youtube.com.

↩ -

5

For an excellent popular account of this and other revisions of pre-Columbian history, see Charles Mann, 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus (Knopf, 2005).

↩ -

6

The term “first contact” is frequently misunderstood to mean that the indigenous people involved have no knowledge of the existence of whites. In general, ethnographers use it to mean that such tribes strenuously avoid coming into contact with “others,” or “strange people” whom they are very much aware of and fear.

↩