In the latter half of the fifteenth century, the artists Andrea Mantegna and Giovanni Bellini ruled over painting in northern Italy. Closely related—Mantegna was married to Bellini’s sister —the painters sometimes took great interest in each other’s work, and occasionally made pictures of the same subject matter. Yet they pursued almost wholly dissimilar visions of professional and artistic success. In nearly every aspect of their art, from their sources of inspiration to the media they painted in and the themes they explored, they made choices of a markedly different character.

The divergent nature of their artistry was a subject of comment even in their own day and it has continued to excite interest in the modern era, engaging the attention of Bernard Berenson, Roger Fry, and many other historians and critics. Thanks to a pair of exhibitions currently on view in Europe—one about Mantegna at the Musée du Louvre in Paris and one about Giovanni Bellini at the Scuderie del Quirinale in Rome—we can now come closer than ever before to understanding the heart of their colossal, yet vastly differing, achievements. It is an opportunity not to be missed. Viewed together, the two exhibitions reveal much of what was possible in Italian painting at the end of the fifteenth century.

1.

Andrea Mantegna was the older and more precocious of the two artists. Born in 1431 in a small village outside of Padua, he was a child prodigy, becoming an independent professional artist by the time he was seventeen. So rapid was his ascent that he won his first commission for a major fresco cycle the same year. Finished around 1457, the resulting pictures in the Ovetari chapel in the church of the Eremitani in Padua rank among the greatest fresco paintings in the history of Renaissance art. (They were largely destroyed by a bomb dropped on Padua in 1944.) To judge from old photographs and the surviving fragments, two qualities were especially prominent in these works. One was the clarity in the representation of space; the other was the breadth of antiquarian learning in the depiction of classical costume and architecture. By both measures, the paintings far surpassed any other fresco cycle of the early Renaissance, including the Brancacci chapel in Florence by Massaccio and the paintings of the Legends of the True Cross in Arezzo by Piero della Francesca.

Although there is no way for the exhibition to represent what Mantegna achieved in the Ovetari chapel, the opening rooms of the show nonetheless give a sense of the first stirrings of his impetuous genius. On view, for example, is one of his earliest surviving paintings, made when Mantegna was only about sixteen. This shows Saint Mark staring out from a window; he juts his right arm beyond the window ledge, bending it back at the elbow in order to support his head with his hand, and a book leans against the other side of the window frame. Both the arm and the book are drawn in perspective and although neither is perfect in its foreshortening, they seem to shoot out at the viewer.

Evident here, too, is the artist’s exquisite sensitivity in the depiction of light. Mantegna lovingly seeks to capture the subtlest gradations in radiance and tone; this is especially true of the underside of the arch of the window as the illumination shifts from cool shadow on one side to full sun on the other. The picture also displays Mantegna’s supreme gift for representing the characteristic texture and sheen of different objects, an endeavor that was to fascinate him all his life. In the relatively small space of the picture, he shows off his ability to portray an extraordinary variety of materials, such as marble, leather, brass, paper, and fruit; even the saint’s halo is seen to have its own distinctive luster.

The picture proclaims the magnitude of his intellectual ambition as well, for surely he wanted it to rival the legendary trompe l’oeil paintings recorded in classical literature, such as those by Zeuxis and Apelles. Padua was the site of one of the most important universities in Europe, and Mantegna’s intelligence, talent, and learning attracted the attention of humanists. About the time he painted this image, the first poem in his praise was written, celebrating his capacity to make figures appear “truly life-like and real.”

The interest and approval of humanists became a determining force in his career. Around 1456 he was hired by Gregorio Correr, the abbot of the Benedictine monastery of San Zeno in Verona, to paint the high altarpiece for the church. In his youth Correr had been a student at the Casa Giocosa, a school funded by the Gonzaga family in Mantua and run by Vittorino da Feltre, the leader of the humanist reform of education. What makes this especially important is that Leon Battista Alberti seems to have written the original Latin edition of On Painting, the first postclassical treatise on art, specifically for Vittorino’s pupils to study. In the era before printing, when texts circulated only in manuscript, this means that Correr was likely among the earliest readers of the book.

Advertisement

Possibly with Correr acting as an adviser, in the San Zeno altarpiece Mantegna created one of the landmarks of Renaissance painting. The main field of the picture shows the Madonna and Child enthroned in an open portico with four saints standing to either side. The figures are life-size and have a solemn grandeur, made all the more impressive by the heavy mantles they wear. The heavenly portico is composed of classical piers and lintels, embellished with colored marble panels and white marble reliefs, and the space of the picture has a degree of depth greater than in any earlier Italian panel painting.

It was impossible to bring the main field of the San Zeno altarpiece to the Louvre for the exhibition, but the organizers have brought together the three predella panels, representing the Agony in the Garden, the Crucifixion, and the Resurrection, which are normally divided between the Louvre and the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Tours. Reunited here for the first time since 1956, they form one of the unforgettable highlights of the show.

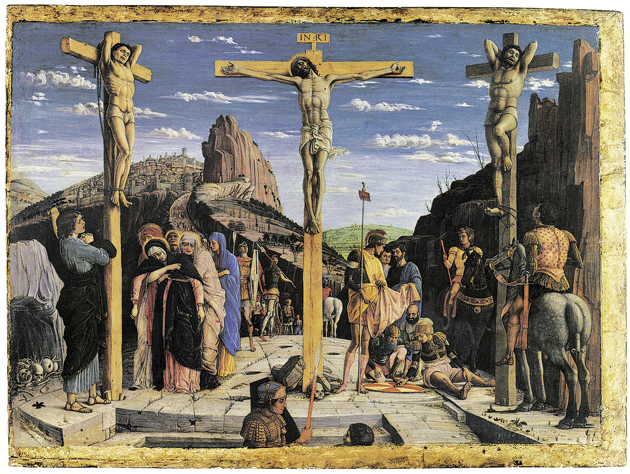

That Mantegna made these panels according to the precepts of Alberti’s theory of painting cannot be doubted, and they are among the first examples of an artist responding to On Painting. For example, in The Crucifixion (see illustration on page 16), the rocky ground is lined with a series of grooves between the stones, and these provide the rectilinear grid necessary for the depiction of space according to Alberti’s rules of single-point perspective. Even more tellingly, Mantegna has followed Alberti’s recommendations on how to construct an istoria, a narrative image that is both dignified and affecting. Alberti suggested that the composition of an istoria should have an ordered clarity, like a periodic sentence constructed according to the rules of classical rhetoric, in which each element is set in balance with another, and all contribute to the harmony of the whole.

Mantegna structured his composition as a series of contrasts. The most obvious of these is formed by the two groups flanking Christ’s cross. To the left, Mary is shown collapsing in grief, while three wailing women struggle to support her body and a fourth looks on with intense sympathy. To the right, soldiers gamble for Christ’s clothes, indifferent to the suffering they have caused, and intent solely on the outcome of their game. Similarly, near the right edge of the picture we see two centurions on horseback, one gazing up in awe at the crucified men, the other looking down in boredom at the gambling soldiers. There are many such antithetical details in the picture, and there are also contrasts of a more general kind: for example, the silence of the dead versus the sounds of the living; and the motion of the soldiers marching in and out of the scene as opposed to the fixity of the saints overcome at the foot of the cross.

Another explicitly Albertian element of the painting is the figure of Saint John, seen in profile in the left foreground, his hands raised in prayer, and calling out in torment as tears stream down his face. Surely Mantegna conceived of his placement and expression in relation to Alberti’s recommendation: “In an istoria I like to see someone who admonishes us and points out to us what is happening there…or invites us to weep or laugh with them.” The painting is remarkable for its vividness and emotional force: looking at it, you almost believe you can hear the dull rattle of the soldiers’ dice and the high-pitched wail of the saints.

While Mantegna was finishing the San Zeno altarpiece, Ludovico Gonzaga, the ruler of Mantua, invited him to become his court artist. Ludovico, too, had studied at the Casa Giocosa with Vittorino da Feltre, and he was closely associated with Alberti. Indeed, Alberti had dedicated the Latin edition of On Painting to Ludovico’s father, Gianfrancesco Gonzaga, who was also Vittorino’s patron. Moreover, about the same time that Ludovico employed Mantegna, he also hired Alberti as an architect and adviser.

Mantegna moved to Mantua in 1460 and served the Gonzaga family until his death in 1506. It is one of the longest continuous relationships between an artist and employer in the history of European art. To work almost exclusively for one family in one town for more than forty years proved to be both a stimulus and a limitation for Mantegna. As a salaried employee, he was required to do nearly whatever they asked, from designing decorations for their houses to keeping them company when they felt lonely or bored. Mantegna was intensely proud and easily angered; no doubt at times he found life in service to be infuriatingly dull and frustrating. Moreover, his artistic production was chiefly determined by the Gonzagas’ needs, not by his interests. In his youth, he had evolved at blazing speed; after moving to Mantua, his style of painting barely ever changed.

Advertisement

Nonetheless, in the course of working for three generations of the family, at times he was able to give noble expression to some of his deepest concerns. For example, he satisfied his love of antiquarian erudition by painting for Francesco Gonzaga nine gigantic canvases depicting the Triumph of Julius Caesar, the largest and most elaborate pictures of the subject made in the Renaissance, which since the seventeenth century have been in the Royal collections at Hampton Court near London. Similarly, for Francesco’s wife, Isabella d’Este, he painted two ravishingly beautiful mythological allegories as part of the suite of pictures by several artists for her studiolo, or private chamber. The paintings for Isabella are in the permanent collection of the Louvre, and can be seen on any regular visit to the museum. But to view them in the exhibition with one canvas from the Triumph series and prints made after them gives an acute sense of the peculiar mix of fantasy and learning that characterized the classicism of the Gonzaga court.

It was in Mantua, too, that he could fully explore the magical trickery of trompe l’oeil, in his work on the so-called Camera degli Sposi in the Ducal Palace there. The tableaux vivants of the Gonzaga family painted on the walls of the room are impressive, but what is truly astonishing is the ceiling, with its depiction of reliefs in white marble, and its painted oculus that appears open to the sky above. For over one hundred years, from Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel to Annibale Carracci in the Palazzo Farnese, whenever an artist attempted to make an illusionistic ceiling painting, he did so in emulation of Mantegna and the Camera degli Sposi.

To understand Mantegna’s art, it is not enough to describe his intellectual interests or his artistic gifts. It is also important to note his personal tendencies in representing emotion. Here he was an artist of extremes. With some subjects, especially the Madonna and Child, he makes the figures look severe and remote, as if they were lost in thought. Their features have the stillness and the regularity of a mask, and there is a sense of isolation about them, even when the narrative demands that the figures interact. As Roger Fry, the English critic, has written:

In some of Mantegna’s Madonnas something altogether different emerges—something so strange, so unrelated to ordinary human life, that we are at a loss to define it or analyze the impression it makes…. The sense of strangeness and mystery is far stronger than any recognizable emotion.

Yet with other subjects Mantegna displays an acute sense of how to depict figures in states of anguish and torment. For instance, in The Agony in the Garden (National Gallery, London), the three apostles at the foot of the hill seem to toss and turn in restless sleep, and their mouths are open as if they are snoring or breathing heavily. Images of this scene always stress the weakness of the apostles as characters, but no one else ever made them seem so bestial in their physicality. Perhaps even more extraordinary is the look on the face of Christ in the great Pietà with Angels from Copenhagen. Surely Christ’s bitter grimace is meant to evoke the abandonment he felt on the cross as he called out “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” moments before his death.

Although it is a remarkable exhibition, the show in Paris has a woeful installation. The wall colors—such as prune and liver—are of such strong flavors as to distract from the paintings. Worse still, like cheap fluorescent lamps, the lights have a perceptible oscillation and a harsh cast, and they are focused on the walls rather than the pictures. The effect is garish and unpleasant.

2.

In contrast to the industrial feel of the Paris show, the Giovanni Bellini exhibition in Rome looks like a display of exotic jewelry. The galleries are completely dark and only the paintings, hung in niches cut into the walls, are illuminated. This would not be a problem, except that the lights on the paintings are tinged with two different hues, pale copper and steel blue. The colors are paired to balance warm and cool tones, and from a distance of more than ten feet or so, the effect is not too distracting. However, if you need to stand closer, as you must during peak visiting hours in the early morning or late afternoon, the illumination appears uneven; in these conditions, some pictures lose all their glory.

The show brings together sixty-two paintings by Bellini, about two thirds of the surviving works. Some of his greatest masterpieces are absent, such as the Saint Francis from the Frick Collection, the San Giobbe altarpiece from the Accademia, and the Madonna and Child with Saints from the church of San Zaccaria. Nonetheless, any show about Bellini is a revelation; this is especially true since there has not been a major exhibition of his work since 1949.

The shape of Giovanni Bellini’s career was completely unlike Mantegna’s. Probably born in the late 1430s, Giovanni was the son of Jacopo Bellini, the greatest Venetian painter of the mid-fifteenth century. Giovanni worked in his father’s studio until sometime in the 1460s, and later in life he occasionally collaborated with his brother Gentile, who was especially renowned for portraits and cityscapes. By the 1470s Giovanni had emerged as the leading artist of Venice, a reputation he retained until his death in 1516. For example, when Albrecht Dürer visited the city in the early sixteenth century, he wrote home that Bellini was “the best in painting.”

Unlike a provincial court where there was one privileged artist and one dominant patron, Venice was a large, mercantile republic where many artists contended for success, and many patrons competed for prestige. This resulted in a more open market and a more rapid pace of artistic growth. To succeed, most artists had to specialize and make one work after another of a certain type or theme. But they also had to adapt continually, as taste shifted and new styles and new techniques developed.

No Venetian artist of the fifteenth century exemplifies this dynamic better than Giovanni Bellini. Early in his career he was already recognized as the top specialist in two formats—the small devotional picture and the large altarpiece. Furthermore, within these formats he was known especially for three themes. For the altarpiece, he concentrated on the so-called sacra conversazione, typically an image of a few standing saints gathered around the enthroned Madonna and Child. For the small devotional picture, he concentrated on the themes of the Madonna and Child and the Dead Christ.

The demand for paintings of these subjects was constant, but over his career of more than fifty years Bellini never ceased to look for new ways to make these images more beautiful and more affecting. His incessant effort at revision changed the history of art. As Bernard Berenson so memorably stated:

For fifty years Giovanni Bellini led Venetian painting from victory to victory. He found it crawling out of its Byzantine shell, threatened by petrifaction from the drip of pedagogic precept, and left it in the hands of Giorgione and Titian, an art more completely humanized than any that the Western world had known since the decline of Greco-Roman culture.

Bellini is widely celebrated as a pioneer among Italian artists in the use of oil as a medium for painting. In comparison with egg tempera, the traditional medium of earlier Italian art, oil has many advantages, including greater transparency, more luminosity, and vastly increased ease of blending to achieve an infinite variety of hues and subtle gradations of tone. This enables superior three-dimensional modeling of form and more accurate depiction of the reflective properties of surfaces. It also makes it possible to portray landscape, atmosphere, and light with far greater accuracy and detail.

He learned the superiority of oil from studying pictures imported from the Netherlands where it was the standard medium. Looking at works by painters such as Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, and Petrus Christus, he could see naturalistic effects that were simply impossible to obtain by the traditional methods of Italian painting. Antonello da Messina, another of the first Italian artists to adopt oil, worked in Venice in 1475–1476, and the example of his work inspired Bellini to experiment even further with the new medium.

In addition to painting with oil, Bellini also changed some fundamental characteristics in the design of the altarpiece. He made it taller than it had typically been before in Italy. For example, his Baptism of Christ from Vicenza, on view in the exhibition, is nearly twice as high as Mantegna’s San Zeno altarpiece (see illustration on page 14). Bellini used this extra height to give unprecedented amplitude and grandeur to the setting. In the Baptism of Christ the figures stand at the front of a landscape of spectacular beauty, whose deep vista extends to icy blue mountains far in the distance. Looking at this work, it is easy to see why he is often considered one of the inventors of landscape painting. In other works, such as the altarpieces of San Giobbe and San Zaccaria, Bellini created another new solution, in which the sacred figures stand in a magnificent architectural space suggestive of an apse or chapel in a church. He lavished great care on these backgrounds, depicting their exquisite details and their golden light to make them appear credible and yet more sublime than any building seen on earth.

Perhaps most important of all, Bellini gave new life to the presentation of the saints. As in earlier sacre conversazioni, he depicted them in contemplation and prayer. But whereas other artists often made the figures seem inert and remote, Bellini showed the saints to be deeply engaged: they may be standing still, but they are fully active in their interior life of the mind and the spirit. For instance, when we look on the great altarpiece from Pesaro, we can see the intensity of love that animates Saint Francis and Saint Paul as they pray, and the desire for wisdom that propels Saint Peter and Saint Jerome as they read.

Bellini also thoroughly revised the private devotional image. As with the altarpiece, he changed its size, making it much larger than it had been before. For example, the Madonna and Child with Two Saints, over three feet wide, is four times bigger than Christ Crowned with Thorns (National Gallery, London), a contemporary devotional image by Dirk Bouts. As we can see in Bellini’s painting, he also increased the scale of the figures so that they appear to be life-size, and he represents them in half-length. Before Bellini, devotional images typically showed either the entire figure depicted on a small scale or only the head up close and very tightly framed. By contrast the figures in Bellini’s paintings are on a natural, human scale. They seem immediately present, too, for they stand so close to the viewer that they look as though one could reach out and touch them. Bellini made all these changes to encourage a sense of rapport between the viewer and the saints in the painting. These supremely beautiful figures seem to invite the viewer to enter their tender realm of empathy and love.

Throughout his long career of innovation Bellini was inspired by one ideal above all. This was the desire to create an apparition of the miraculous for the viewer to behold. Of course, all religious art of the time expressed the desire for hierophany, the appearance of the sacred on earth. Yet with greater focus than any artist before him, Bellini concentrated on recreating the moment and the experience of revelation. This is evident, for example, in the deeply moving Resurrection that he painted in the late 1470s. In this vision of Christ rising from the grave on Easter morning, we see four guards near the tomb in various states of awareness: two are seated in slumber or stupor, two are standing alert and look up at the Savior. The one at the right is bathed in the light shining from Christ and this light is even reflected in the guard’s eyes. It is the spark of recognition, and it contrasts with the darker tones of his face so that we can see, in his moment of conversion, both his enlightenment and his remorse.

The guard is an eyewitness of the Resurrection, a point stressed in the apocryphal Acts of Pilate, and other religious literature popular in the Renaissance. And according to these texts his reception of grace bears a command: behold and testify. In a sense, Bellini tries over and over again in his paintings to induce this experience. He wants us to imagine what it would have felt like to be that guard; or to have seen the Virgin lovingly cuddle her Child; or to have wept with the angels over Jesus dead in his tomb. He wants us to be witnesses too.

Bellini surely knew how fundamental the concept of being a witness was to the foundation and the ideals of Christianity. He knew that the Bible says that Saint John the Baptist “came as a witness to bear witness of the light” (John 1:7; Tyndale translation); that the Apostolic mission begins with Jesus’ command “Ye shall be witnesses unto me” (Acts 1:8), and that throughout the Acts of the Apostles the apostles are called witnesses.

This is the source of the moral urgency in his art, and it is most evident in those images where a sacred being stares straight at the viewer. In the Baptism of Christ from Vicenza, we see the drop of water falling from Saint John’s cup and we see the dove of the Holy Spirit descending from God the Father above. As the water touches Jesus’ head, we see the radiance of divine illumination spread behind His head. The account of the scene in the Gospel of Saint John concludes with the Baptist’s words, “And I saw, and bare record that this is the Son of God.” Christ’s unwavering gaze implies a kind of direct and unyielding address. Bellini, I think, meant this gaze both to recreate the sensation of revelation and to pose a question: “Now that you see, will you too become a witness like the Baptist and the Apostles?”

Facing straight on and with the eyes open, Christ’s head has something of the look of an icon or the Holy Face of Veronica’s veil. And yet in the extremely sensitive description of the color and details of the hair, skin, and lips, the exquisite modeling of the light and shadow falling across the head, and the careful treatment of the highlights reflected in the eyes, it appears more like one of Bellini’s great portraits of a contemporary, such as his picture of Doge Leonardo Loredan in the National Gallery, London. About the time Bellini made this picture, a Venetian poet praised his ability to make Jesus look “more human and more divine.” The capacity to combine the sacred with the earthly was the key to his art, and it was this he passed on to Giorgione, Titian, and the next generation in Venetian art.

This Issue

January 15, 2009