Few expected very much of Franklin Roosevelt on Inauguration Day in 1933. Like Barack Obama seventy-six years later, he was succeeding a failed Republican president, and Americans had voted for change. What that change might be Roosevelt never clearly said, probably because he himself didn’t know.

Herbert Hoover, the departing president, had left behind an economic cataclysm. Since the 1929 stock market crash the economy had been spiraling inexorably downward for more than three years. The country had always experienced episodic “panics” and “recessions,” but nothing this bad. As Anthony J. Badger writes in FDR: The First Hundred Days, “Americans had never been there before.”

Roosevelt’s declaration that Americans had “nothing to fear but fear itself” was a glorious piece of inspirational rhetoric and just as gloriously wrong. Banks across the country had been failing for months and thousands more were on the brink as he took the presidential oath. Unemployment stood officially at 25 percent but was actually closer, Badger estimates, to 33 percent. “Farmers had been crushed by catastrophic price falls, drought, and debt. A thousand homeowners a day were losing their homes.”

Hoover, a rigid conservative intellectual, refused to abandon the old-time religion of market capitalism and was still waiting for the business cycle to work its magic. One of the inescapable sounds of the era was of Americans everywhere sardonically telling each other, “Prosperity is just around the corner.” It was the message of Hoover’s reelection campaign, and he had lost all but six of the forty-eight states.

To cope with the economic catastrophe, Americans had elected a man whom many of the finest minds of his generation considered an intellectually second-rate, rich mama’s boy, whose obvious charm obscured a deep shallowness.

In The Defining Moment, Jonathan Alter describes the young Roosevelt’s futile efforts to win the admiration of influential journalists, trying, for example, to charm Walter Lippmann, “the most prestigious syndicated columnist of that or any other era,” only to find himself dismissed in a Lippmann column as “a pleasant man who, without any important qualifications for the office, would very much like to be president.” In private correspondence Lippmann was even crueler: “a kind of amiable boy scout,” he wrote to a friend.

H.L. Mencken, after pronouncing Roosevelt “one of the most charming of men,” wrote that, like most such men, he left the impression of being “somewhat shallow and futile.” Other important journalists—Herbert Bayard Swope, Frank Kent, Arthur Krock—seemed to agree. Even more remarkably, after his election some of these very critics were saying he should be given dictatorial powers. Such was the sense of panic about the Great Depression as he took office.

“The nation expected Roosevelt to claim the powers of a dictator, or close to it,” Adam Cohen states in Nothing to Fear. He quotes Senator William Borah, the highly respected progressive Republican from Idaho, declaring himself ready to put politics aside and “give our incoming President dictatorial power within the Constitution for a certain period.”

“If this country ever needed a Mussolini, it needs one now,” said Senator David Reed, a Pennsylvania Republican. Even Lippmann, having dismissed candidate Roosevelt just a few months earlier, wrote that the use of “‘dictatorial powers,’ if that is the name for it—is essential.'”

Roosevelt addressed the dictatorship question in his Inaugural Address, saying he intended to work with Congress on the nation’s problems and hoped the president’s traditional powers would suffice to help solve them. If not, he would ask for a “temporary departure,” asking for “broad Executive power to wage a war against the emergency, as great as the power that would be given to me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.”

As Cohen observes, this was “the most radical” passage in the Inaugural, “with its understated suggestion of autocracy.” He notes that “it received an enthusiastic response from the crowd.” Adolf Hitler had become chancellor of Germany just over one month earlier; Benito Mussolini, as Italy’s prime ministerial dictator since 1922, was fairly popular in the United States. In the astonishing tumult of legislation that immediately followed Roosevelt’s inauguration, Congress proved so eager to vote immediately for anything he wanted that he seemed to have been granted dictatorial power without asking for it.

The early commentators who put down the pre-presidential Roosevelt as an empty-headed young lightweight, all ambition and no talent, now seem comically wrong to a modern book-reading, movie-going, television-watching, legend-loving American public conditioned to think of him as one of the presidential giants on the order of Washington and Lincoln.

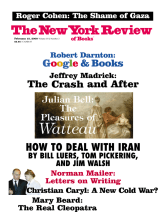

The appearance of these three—three!—fresh histories of Roosevelt’s first hundred days in the White House testifies to the large space he occupies in America’s political psyche, for as good as the books of Messrs. Alter, Badger, and Cohen seem to be, there is little in them that has not been long since recorded by earlier historians, memoirists, journalists, gossips, publicity agents, and politicians with grievances to be settled.

Advertisement

Besides three treatments of the Hundred Days there is a new full-length (888 pages) biography, Traitor to His Class, starting with FDR’s Delano grandfather, who got rich in the China trade (opium inevitably included), and ending with FDR’s death in Warm Springs in the embarrassing company of Lucy Mercer Rutherfurd, for whose love he might once have divorced Eleanor had he not loved politics more.

Its author, Professor H.W. Brands, writes with an ease not common among academic historians, and he is not above rewarding the reader with fragments of irrelevant but salacious old Washington scandals. Discussing Franklin’s youthful philandering, he throws in some history of early-twentieth-century adultery in Washington, not omitting the story of Alice Roosevelt, Teddy’s daughter, discovering her husband— House Speaker Nicholas Longworth, no less!—and her good friend Cissy Patterson “coupled on the floor of her bathroom.”

Vast as the Roosevelt literature is, biography nowadays must also compete with theater, movies, television plays, documentaries, and “docudramas,” though not yet an opera. From these sources millions have become familiar with FDR’s heroic comeback from the polio that left his legs forever useless and seemed to end his hopes for a political career. Who knows how many millions have been moved to tears by actors dramatizing his determination not to have his life defined by a wheelchair?

Most Americans also know about Eleanor’s emotional devastation upon discovering his affair with Lucy Mercer (“the bottom dropped out of my own particular world”) and know that this ended physical intimacy in their marriage, and that Eleanor nevertheless helped nurse him through the battle with polio and became an important figure herself in American public life.

Brands revisits all the familiar material with a storyteller’s touch, making Traitor to His Class a good beginner’s book for readers seeking a fuller sense of FDR’s life and times than the entertainment media can provide. He also conveys a sense of the Roosevelt political genius at work.

What so many observers failed to grasp before 1933 was that Roosevelt, with all his inadequacies, was a great politician, and to be a great politician is no small thing. The art of it has fascinated Shakespeare and many a philosopher—Aristotle, Plato, and Machiavelli among them. Roosevelt seems to have been born with that unique political gene that empowers otherwise ordinary men of no special intellect to shape and command events. If Americans were slow to see it in Roosevelt, perhaps it was because tradition accustomed them to look down on those they called, usually with a sneer, “politicians.” Or perhaps the political genius was merely dormant potential until the ordeal with polio brought it into full flower.

The “charm” that so many noticed in the young Roosevelt was often thought to be cover for an empty head. “He’s really a beautiful looking man, but he’s so dumb,” said the mother of his financier friend James Warburg, watching him in Washington as assistant secretary of the Navy during World War I.

Professor Badger’s thumbnail summary of his early career suggests why Washington in those days found him easy to dismiss: the adored only child of parents with old New York money, he was schooled at Groton and Harvard, studied law at Columbia, and after “little more than a desultory attempt to earn a living as a lawyer and in business” went into politics with the idea of someday becoming president.

Grenville Clark, who knew him as a young lawyer, remembered him in 1907, only twenty-five years old, talking about becoming president. Clark, who became a distinguished Wall Street lawyer, recalled his “saying with engaging frankness that he wasn’t going to practice law forever…. He wanted to be and thought he had a very real chance to be president.” Quoting Clark, Brands writes:

“I remember that he described very accurately the steps which he thought could lead to this goal,” Clark continued. “They were: first, a seat in the State Assembly, then an appointment as Assistant Secretary of the Navy…and finally the governorship of New York. ‘Anyone who is governor of New York has a good chance to be President with any luck’ are about his words that stick in my memory.”

Theodore Roosevelt’s example must have made the presidency seem a not implausible goal for young Franklin. Though his own family link to TR was somewhat remote, his marriage to Teddy’s niece Eleanor—the only daughter of Teddy’s deceased brother Elliot—brought him into the White House family circle, close enough perhaps to have thought of TR as “Uncle Ted.” On the day he and Eleanor were married, the presidential Roosevelt had overshadowed bride and groom by turning up to give the bride away, then becoming the life of the reception party. “Well, Franklin, there’s nothing like keeping the name in the family,” Teddy told his new nephew. Franklin, we now know, was soon thinking of also keeping the presidency in the family.

Advertisement

He was adapting public-speaking technique to the modern audience for whom the microphone provided a more intimate experience than the old political barn-burner oratory did. By the time he became president he could address an audience of millions as “my friends” and leave each listener with the sense of hearing a personal message from an old acquaintance. His masterful command of radio—so new that Al Smith still called it “the raddio”—made his “fireside chats” a vital instrument for shaping public opinion. As early as 1928, Brands writes, he was telling fellow Democrats that radio would supplant the press as the primary means of connecting candidates to voters:

Today at least half of the voters, sitting at their own fireside, listen to the actual words of the political leaders on both sides and make their decision based on what they hear rather than what they read. I think it is almost safe to say that in reaching their decision as to which party they will support, what is heard over the radio decides as many people as what is printed in the newspapers.

Still, the sense that he lacked the stuff to become a major political achiever endured in spite of his having run as the Democratic vice-presidential candidate in 1920, before the polio, and served as governor of New York, after polio. As governor he had been regarded as little more than a stand-in for Al Smith, and 1920 was a year of such crushing defeat for Democrats that a vice-presidential loser could only have seemed too trivial to remember.

And so, having taken the presidential oath on March 4, 1933, Adam Cohen writes, he proceeded during the next hundred days to create “a revolution”:

Roosevelt shepherded fifteen major laws through Congress, prodded along by two fireside chats and thirty press conferences. He created an alphabet soup of new agencies—the AAA, the CCC, the FERA, the NRA—to administer the laws and bring relief to farmers, industry, and the unemployed…. Within days he had declared a national bank holiday and signed the Emergency Banking Act, which immediately put the banking system on a firmer footing.

He also took America off the gold standard, created the Tennessee Valley Authority, established two major public works programs, and, for the first time, provided regulation of stock issues. The first advances were made toward a minimum wage, a ban on child labor, and legal support for union organizing. Arthur Schlesinger Jr., the master of Roosevelt biography, called it “a presidential barrage of ideas and programs unlike anything known to American history.”

This period, known ever since as “the Hundred Days,” made profound changes in government’s attitude toward the citizen and created the ideological conflict that animated American politics through the twentieth century to the present day. No Republican president since Roosevelt’s death has tried harder than the departing George W. Bush to undo what Roosevelt did. One day during the Reagan years I asked a Republican friend with an important job at the Capitol what the Senate was doing that afternoon. “We’re killing the New Deal again,” he said. George Bush was still at it a quarter-century later as his term ran out.

“The Roosevelt revolution created modern America,” Cohen writes.

When he took office, the national ideology was laissez-faire economics and rugged individualism, and the federal government was small in scope and ambition. “The sole function of government is to bring about a condition of affairs favorable to the beneficial development of private enterprise,” Hoover had declared in 1931. Roosevelt and his advisers introduced a new philosophy, one that held that Americans had responsibilities to one another, and that government had a duty to intervene when capitalism failed.

Now George Bush, whose ideology was close to Hoover’s, has ended his presidency by intervening with hundreds of government billions to save capitalism from its own failure. Using government money on a vast scale to keep the financial markets working, then to save the automobile industry from bankruptcy, has edged the Bush administration deep into a kind of happenstance socialism.

Everything Republicans have stood for since Barry Goldwater denounced Eisenhower Republicanism as “a dime store New Deal” and Ronald Reagan proclaimed that government was the problem, not the solution, seems mocked by these events. Suddenly the old-time religion had been proven hollow in the most embarrassing manner conceivable: the most conservative administration in eighty years was forced to call on government to save capitalism from itself.

The blooming of literature about the Hundred Days probably has a lot to do with Barack Obama’s assuming the presidency at a moment of economic breakdown just as Roosevelt did seventy-six years ago. Parallels like this are hard for historians and journalists to resist. Could history be repeating itself? It never does, of course. Still, there are similarities too interesting to be discarded without a glance.

Might Obama, who, according to his aides, has been reading Alter’s book, not profit from FDR’s experience? Of course, but is he likely to emulate Roosevelt’s aggressive style by hinting that he is prepared to meet political resistance by resort to autocratic measures? Highly unlikely: for one thing, because his style suggests he favors compromise over combat. For another, though George Bush’s status as a wartime president could make a scared and timid Congress knuckle to autocratic behavior, the present economic breakdown is obviously not terrifying enough for Obama to engage in such presidential strutting. Republican senators are not yet yearning for a Mussolini to save us from the greedy bunglers of Wall Street.

Are we truly very close to another Great Depression? Paul Krugman thinks so. His New York Times column of January 5 said, “Let’s not mince words: This looks an awful lot like the beginning of a second Great Depression.” Many economists have been saying for months that we may soon find ourselves in something very nasty—“worse than anything since the Great Depression” has become a standard line. Why we are in this situation seems utterly incomprehensible. Who but a Wall Street trader or a professor of economics can say exactly what a “derivative” is, or a “credit-default swap,” and why they are responsible for so many people losing their jobs?

Is it really true that Wall Street’s money wizards—“masters of the universe,” as Tom Wolfe called them—found ways to make billions by selling houses to people with no money to pay for them? This is the sort of thing that FDR would have dealt with in a fireside chat, leaving the public with a reassuring sense of knowing what the President was up to and why, and President Obama has already started trying to adapt the technique to the electronic age. Since the election he has become the first president to deliver a weekly “radio” address using both audio and video and transmitted on YouTube and across the Web.

It was clear soon after his election that Obama, like FDR, wanted to start dealing with the economic crisis immediately after his inauguration. Since early December the constantly repeated phrase from his people has been “hit the ground running.” He assembled his cabinet and filled most of his close White House advisory positions with unusual speed, as though he wanted everyone ready to go to the office and start work as soon as the Chief Justice finished administering the oath.

In this he was following the Roosevelt example. Action was what FDR had promised in 1933—action and experiment. Whether experiment interests Obama as it interested FDR is a deep question since, for one thing, FDR looked to experimentation to find out what his own philosophy would be. Frances Perkins, his secretary of labor and the first woman ever to serve in a presidential cabinet, later wrote that he had no coherent philosophy to guide his actions. Often, it appears, he had very little knowledge either. Raymond Moley, his chief policy adviser during the Hundred Days, played a major role in the 1933 banking crisis and afterward said he doubted that “either Roosevelt or I could have passed an examination such as is required of college students in elementary economics.”

“The notion that the New Deal had a preconceived theoretical position is ridiculous,” Perkins later said. “The pattern it was to assume was not clear or specific in Roosevelt’s mind, in the mind of the Democratic party, or in the mind of anyone else.”

Uncertainty on this scale is hard to imagine in the highly organized and obviously cerebral Obama. Yet he seems much like Roosevelt in not being wedded to any ideological position. FDR in his campaign had promised “to take a method and try it: If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something.” Obama makes Democratic liberals fidgety because of a pragmatic tendency that might prompt him to settle for compromised programs rather than support traditional progressive ideas that require a terribly high price to enact. In his readiness to try to find what will work, he is like Roosevelt.

Roosevelt, however, chose from a very wide selection of ideas. These came not from the somewhat musty leaders of the regular Democratic Party, though according to Jonathan Alter it was Ed Flynn, boss of the Bronx, who awakened Roosevelt to Pope Leo XIII’s 1891 encyclical, Rerum Novarum, that “shocked the world” by proclaiming workers’ rights to form labor unions and receive a “just wage.” Most, however, came from what a reporter called “the Brain Trust.”

They were led by a group of Columbia University lawyers who ran what Professor Brands calls “a kind of graduate seminar for a law school dropout who wanted to be president.” The subject was the state of the world and what needed to be done about it. The group was expanded to bring in social workers like Perkins and Harry Hopkins and the agricultural scientist Henry Wallace.

It was a group to chill the blood of today’s conservative journalists who have been praising Obama’s choice of advisers, most of whom are old Washington hands, many with experience in the Clinton years, the kind of people likely to provide measured judgment rather than daring ideas. Obama would seem to have cast his destiny with the tried and true, and with the moderate’s readiness to compromise—to “reach across the aisle” is the current cliché—that today’s Washington respects.

The Brain Trust, in contrast, was a group who would be outsiders in Washington today, and they were competing among themselves for Roosevelt’s mind and soul. “He was a progressive vessel yet to be filled with content,” wrote the Columbia professor Rexford Tugwell. Roosevelt’s lack of ideology seems curious in view of the fact that he had been thinking how to be president since the age of twenty-five. Alter suggests that in his early days as a candidate he was shopping for a philosophy to fit the political needs of the day. He understood, Alter writes, that “with the economy in shambles it wasn’t smart to believe too much in anything just yet, beyond experimentation and rejection of economic shibboleths.”

As a candidate, in Alter’s view, he was a little bit of a lot of things. Partly an individual rights liberal like Louis Brandeis, partly a big government corporate planner like Hugh S. Johnson. Sometimes a budget balancer, sometimes a budget-busting spender.

Raymond Moley, who was very close to Roosevelt in the early days, told him his view should be that “there is no room in this country for two reactionary parties,” that Democrats should be “a party of liberal thought, of planned action” on behalf of labor, farmers, and small businessmen. And that was what FDR made it when everything looked as hopeless as it could be and there had never been a worse hard time.

Certainly he did not make it by design. Some may say that he blundered his way into it and, what’s more, all that spending did not end the Great Depression either; it took Hitler and World War II to do that. Of course World War II was, among other things, the biggest public works program in American history, which invites the inference that FDR was on the right track before the war, but simply failed to spend enough.

However it is argued, what endures is the revolutionary idea of 1933 embodied in the tumult of the Hundred Days. Perhaps in spite of himself, FDR built for the ages. Now, Mr. Obama, we await another pilgrim.

This Issue

February 12, 2009