An ominous title. Opening the new book by the author of the phenomenally successful and greatly loved Reading Lolita in Tehran (2003), one wonders if it will contain further revelations about the revolution in Iran that she survived, and even triumphed over, by her passion—and her ability to convey that passion—for the classics of Western literature. Actually, it is a memoir of her life growing up in a well-to-do family in Iran, but one soon discovers that it, too, is an act of rebellion against a tyranny.

Unlike her first book, which displays a constant curiosity about and awareness of the world around her, in her memoir the world shrinks to

those fragile intersections—the places where the moments in an individual’s private life and personality resonate with and reflect a larger, more universal story.

Here the silence referred to in the title is not that which a tyrannical state imposes on its citizens, or of the witnesses who choose not to speak, or of the victims who fear to speak—rather, it is about

the silences we indulge in about ourselves, our personal mythologies, the stories we impose upon our real lives.

Yet the imposition of such a tyranny—and the rebellion against it—can be the most powerfully influential element in a life. In Nafisi’s case it is the tyranny of a mother—and so her memoir joins a long procession of books and films by daughters about their mothers and the battles they fought to assert their own womanly identities and tell their own womanly narratives. This procession is such a long one that one feels one surely should have a female counterpart to place beside Oedipus—until one remembers that, according to Freud, “oedipal” is an adjective that can be employed for a child of either sex who desires to exclude the parent of the same sex and usurp that position.

The combat between her mother and Nafisi is established early, in infancy, the mother claiming that the child has refused to nurse and then declined to eat, the child claiming that her mother locked up her toys and would not allow her to play. By the time Nafisi was four years old she had had a major battle with her mother about where in her room her bed was to be placed—by the window or not—and lost. How often the child must have gone to bed in tears. But straightaway another relationship was set up—with the good fairy, her father, smiling, charming, affable, who would place a china dish filled with chocolates by her bed and tell her bedtime stories taken from the Persian classics. So she learned that she

could always take refuge in my make-believe world, one in which I could not only move the bed over by the window, but fly with it out the window to a place where no one, not even my mother, could enter, much less control.

Unlike her mother’s fierce outbursts and persistent demands, her father “lured and seduced” with his stories, his attentions, his charms.

Typically in such narratives, the mother gives all her affection and approval to the son:

I believed my mother loved Mohammad in a way she never loved me. Although she later denied it, she used to say that when he came into the world, she felt here was the son who would protect her.

Perhaps she had reason to want protection: her husband was prone to romantic involvements with women he found more warm and compliant than his wife, and his daughter, when she grew older, even accompanied him on his assignations, sympathized with him, and helped him conceal them from his wife.

It must have been years before the daughter understood what lay beneath her parents’ antagonism. Her mother had married, as a young girl, a man she met at a wedding and danced with, an incident she always described in fantastically romantic terms; but the young man had been terminally ill at the time of their wedding and died shortly after, without, according to her second husband, consummating the marriage. So that relationship remained in her mother’s imagination as pristine, immaculate, idyllic, qualities her second marriage never had the chance to match. Of course such things could not have been obvious to a small child bewildered by adult behavior (any more than several incidents of being fondled by elderly male relatives, frequent visitors in her parents’ hospitable household), but it must have been sensed by her, increasing her sympathy for her father.

Even his family and his hometown were more congenial to her. Esfahan—traditional, austere, historical—was to her a place where poetry was recited, literature and philosophy discussed, truly the home of Iran’s past and culture, unlike Tehran, where they lived, a modern city with no past; what tradition it had was made up according to the needs of the Shah’s regime.

Advertisement

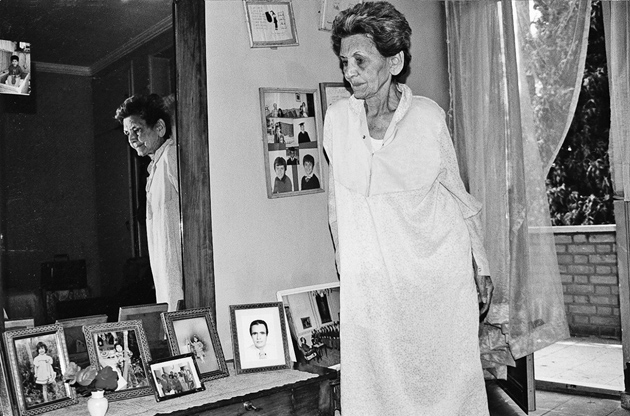

One sees these stark contrasts in Nafisi’s attitude in the photographs reproduced in the book. In those with her beautiful, well-groomed, and elegant mother, she looks apprehensive, her mother authoritative, with her hands on her daughter’s shoulders, holding them in a controlling grasp, both of them with stiff postures and frozen expressions as if in the moment before combat begins. Those with her father, on the contrary, show her with her hand placed trustingly on his shoulder, her head leaning against his, her expression one of tender love.

The polarities must have been so evident, and public, that no one could have ignored them:

After dinner my mother followed me from the dining room to the terrace, with a small plate full of sliced pears, stopping at intervals to push her fork with a pear at its tip into my mouth. I am aware of sideways looks by my uncles and my cousins. Finally, with a theatrical gesture, proclaiming, Please observe my predicament and sympathize! I surrendered and sat opposite her, as if in a staged play, while she forced slices of pear into my mouth.

Nafisi then goes to her room and writes two sentences over and over again on a page in her diary:

I hate pears I eat pears

Eventually the family decided to see a psychiatrist, the friend of a relative, although the mother’s immediate reaction was, “first of all there is nothing wrong with anyone, and second, it is useless anyway, and third, why should one air one’s dirty laundry in public?” The consultation goes as badly as could be foretold. When the conversation is initiated by such generalities as “You know how teenage children are,” the mother replies tartly, “In my time, teenagers did not exist.” They take turns at “consulting” the psychiatrist but when it is her turn, the mother says

she has nothing to hide; unlike the rest of us, she has no secret…. I am a poor housewife. I am a nobody…. And I never felt I had to complain to doctors about my problems. She extends her hand, thanks the doctor with a poisonously sweet smile, and goes out; and we sheepishly follow her.

Such incidents have their comic potential but they tip over into seriously disturbed behavior when one sees how they affected the children. Back at home brother and sister hatch plans:

We could drug her by dropping Valium into her coffee, invite the doctor to come for a social visit and have him diagnose her on the sly. He could hypnotize her…. Poison, what about poison? I say. You want to kill her? No, we give her a little poison and then rescue her; that way she will appreciate life. Ah, she will say. I never knew how precious life was. Or what if the three of us, Father, you, and I, committed suicide. That would teach her a lesson, I say excitedly. Yes, that might be the best solution.

This sounds shocking, but Nafisi explains:

My brother and I had grown accustomed to Mother’s proclivities: like drug users, we needed a shot of drama to get by. When she shouted and accused us of our various crimes we became hysterical, cried, tore up our clothes, and in some cases even tried to hurt ourselves physically.

Had this one note of persecution/paranoia been played throughout the memoir, the reader would have had to build up a resistance to it out of sheer self-defense against the author’s ruthless subjectivity. Please, we would have begun to plead, is there no other point of view? No other side to this story? No other version we might hear?

Fortunately, there are subtexts that provide a structure for this story of unrest and revolt (in the home and the state). In an early section of the memoir a picture of Tehran and its social life emerges that reveals how much it was a European province at the time, at least for the rich and powerful. The salon Nafisi’s mother created and over which she held sway, serving coffee and chocolates to aunts and uncles, bankers and government officials, could have been set in the Paris of an earlier day. In the streets where mother and daughter go shopping, the mother buys Nina Ricci’s L’air du Temps, chocolate is pronounced chocolat, expensive toys are purchased (to be locked up at home), and at Christmas there is even a Baba Noel. One sees how Tehran, rather like Istanbul, had become a colony of Europe, one presided over by Reza Shah Pahlavi, and also why a revolution would one day be staged by the classes that did not benefit from it.

Advertisement

The revolution and its many stages—some sudden, some gradual—provide the other text, as one might expect from the author of Reading Lolita in Tehran. It is the well-to-do father who provides the link between the private and the public worlds since, unlike others in the family, he seeks a public career under the Shah and in the early 1960s is elected mayor of Tehran, causing some consternation and disapproval among them:

My family had always looked down on politics, with a certain rebellious condescension. They prided themselves on the fact that as far back as eight hundred years ago— fourteen generations, my mother would proudly emphasize—the Nafisis were known for their contributions to literature and science.

The election of her father to this political position—and his closeness to the Shah during these years—made them uneasy, and “later, when my father fell out of favour, my parents managed to make us feel more proud of his term in jail than we had ever been when he was mayor.”

It also taught his daughter a useful lesson in how fortunes can change. She had felt proud when she saw a photograph of him in Paris Match being awarded the medal of the Legion of Honor by General de Gaulle, whom he received in his capacity as mayor with a speech he delivered in French, complete with allusions to French literature, but he warned her, “Well, that will cost me, so let’s not be too quick to celebrate.”

Soon enough jealous rivals brought charges against him of corruption and taking bribes, and in 1963 he was imprisoned. In this period father and daughter drew closer together, although the mother tried to dissuade her from visiting him in prison so often. Nafisi baked cakes for her father and “read…avidly and collected” the poems he wrote to his wife. In jail he worked on children’s books, including a translation of the fables of La Fontaine; and he reminded Nafisi of the Persian legends with which he used to regale her, of the great heroes and the trials they had to go through before they were vindicated. “This is the time to be proud,” he would tell her.

After four years in prison, he was exonerated of most of the charges and released, but his public career was at an end and the family felt relieved. Nonetheless, the mother, relentlessly competitive with her husband, sought election to parliament as one of its first female members and was proud when she won; but since by temperament she was drawn to opposition, her role appears to have been one of a critic who was not welcomed or admired. This seems to have been the public position the family often adopted—horrified and unhappy onlookers rather than involved players.

The third subtext—if such a label can be applied to such an insistent theme—is the author’s commitment to literature, the world of books that she chose for herself while still young and for which her mother was, ironically enough, at least partly responsible. When Nafisi was thirteen years old she was sent to school in England at her mother’s insistence. A brief tug-of-war had taken place—was she to have a French or an English education?—and her mother’s faith in a British education won out. Arrangements were made for her to board at the house of “a responsible Englishman” while she attended school in Lancaster—a leap of the imagination and an act of courage in a family and for a generation that had been educated and reared in the old Persian tradition.

The mother accompanied her daughter and “from the moment we arrived she wreaked havoc in that house in order to provide me with the kind of comfort she imagined I needed,” insisting on a shower being installed in the bath (displaying the Eastern horror of bathing in stagnant water) and teaching the maid the correct way to wash and rinse dishes. When the daughter returned from school, a plate of oranges, nuts, and chocolates would be ready for her. When she had trouble learning English, her mother—who had not known a word of the language either—studied the assigned pages of the English text in order to test her and helped her memorize long lists of words every night.

It seems to have been the only time in their lives that they had rapport. Seeing her for the first time in her English schoolgirl’s uniform, the mother breaks into laughter:

Poor Azi, she says with uncommon sympathy. She so seldom laughed or smiled—we knew mainly bitter smiles, reminders of our wrongdoings—that I am caught offguard…. Tears well up in my eyes and she pats my hand.

Nafisi writes,

In some rare moments she would glance at me, her eyes almost brimming with tears, and say, with a shake of her head, Poor Azi, poor, poor Azi!

A photograph from that period during the 1960s, of mother and daughter saying goodbye in the grim, gray, rainy railway station of Lancaster, is the only one that shows any tenderness in their postures—not defiance.

There, in that unpromising setting, the mother sets her daughter in the direction of the study of English literature that was to be her career, her calling, and her saving. It would be many years, many decades, however, before the mother remarked, with bitterness,

“The parent who disciplines a child is always the one who is disliked. It is the indulgent one they want to spend time with.” I should have said, “Yes, you did give me that, you gave us education, and where I am now I owe to you. You wanted your dreams for me.” I should have acknowledged that. But somehow it was all a bit too late.

A crack larger than anyone at that time could have foreseen had been made. The years in Lancaster could hardly have been happy ones—there is not a word to suggest any pleasure—but from that moment Nafisi’s career as an expatriate had been set. After her years abroad, all the dramatic events in Iran could only be of a world to which she no longer entirely belonged. She further removed herself from it by marrying a young man who was then a student at the University of Oklahoma and took her there with him. The marriage did not last long but it was in Norman, Oklahoma, that she became swept up in the student revolutionary movement of the 1970s through the organization the Confederation of Iranian Students. While American students were agitating against the war in Vietnam, the Iranian students were agitating, along with Muslim and Marxist groups, against the pretensions of the Pahlavi regime and its lavish celebrations of the 2,500th anniversary of the Persian empire in the ruins of Persepolis. “The Confederation,” she explains,

was an umbrella organization, composed of groups with different ideological viewpoints, but with time, especially in the US, the most militant and radical ideologies became dominant…turning the teachings of Che Guevara, Mao, Lenin, and Stalin into romantic dreams of revolution.

Nafisi’s second husband, Bijan Naderi, was one of the leaders of the student factions in California, “more cerebral and less ferociously self- assured than most of the other factions.” Immediately after their marriage, he left for Paris to meet the leaders of the movement there. It was at this time that Ayatollah Khomeini was becoming more widely known in Iran:

Too arrogant to think of him as a threat and deliberately ignorant of his designs, we supported him…. We welcomed the vehemence of Khomeini’s rants against imperialists and the Shah and were willing to overlook the fact that they were not delivered by a champion of freedom.

Nafisi and her husband returned to Iran in 1979 when the Shah had been deposed, Shahpour Bakhtiar had been made prime minister, and Khomeini had returned from his exile in France in triumph to adoring crowds. An aunt of Nafisi’s claimed to have seen his image on the moon! But instead of retiring to the holy city of Qom as he had said he would, he stayed to establish a regime more authoritarian than the Shah’s, arresting citizens for such sins as possessing alcohol or playing Western music. The streets were terrorized by vigilantes, the veil made mandatory for women, the legal age of marriage reduced from eighteen to nine, polygamy legalized, adultery and prostitution punished by stoning to death. The principal of the girls’ school Nafisi had attended was tied in a bag and shot or stoned to death. Her father lamented, “No foreign power could destroy Islam the way these people have.” Some members of their family were imprisoned or executed but although Nafisi’s parents were harassed, they escaped a worse fate, ironically because her father had earlier been incarcerated by the Shah.

Nafisi retreated from this maelstrom into teaching at the University of Tehran but that proved no safe haven: she was expelled for her many infractions, such as teaching banned classics of Persian literature and demonstrating against Khomeini’s henchmen, who violently attacked politically active students. She moved to the Allameh Tabatabai University, considered more liberal. Nafisi had by then become a well-known literary critic and her classes at the university were extremely popular, but her energetic teaching once again attracted the attention of the authorities, who attempted to censor and restrict her activities.

After resigning from the university in protest, she ended up teaching a small group of students—mostly women—who gathered at her home on Thursday afternoons to shed their veils and discuss freely and enthusiastically such heroines as Daisy Miller, Elizabeth Bennet, and Lolita, as recounted in Reading Lolita in Tehran. In that book she used her connections with her students and the study of Western literature as a counterpoint to the militancy of the revolution, and so provided a more varied, nuanced, and richer portrait of the times. The emotions she described—passions is a more apt word—were as intense as they are in the current memoir, but her earlier book benefited from its wider scope of experience.

Here her emphasis returns to her own and her family’s story. Nafisi’s parents’ troubled marriage finally ended in divorce, adding to her sense of dissolution and disintegration, and her adulation of her father faded. While she was absent, attending a conference in the US, he married a much younger woman, one whom she had long known and disliked and who proved every bit as demanding as Nafisi’s mother, if cleverer at it. Although he built a house with three apartments in which his former wife and two children could live, he managed to sell or turn over all his property—including entire islands in the Caspian Sea—to the new young wife.

Nafisi, once again living in the same house as her mother—a door connected their apartments—now found their relationship changing, and this takes up the last part of her memoir. In contrast to the earlier section of conflict and revolt, here the mood shifts to one of reluctant sympathy for the abandoned, embittered woman. And the mother, once a threatening and disruptive tyrant to her children, becomes the kind of grandmother to Nafisi’s two children that she had never been as a mother to her own, spoiling them with treats of coffee and chocolates, telling them stories as they lay side by side on a rug for their afternoon naps, and playing cards with them when their parents were out.

She had her moments of defiance and authority still. Having been one of the first women in Iran’s parliament, she was in disgrace with the new regime and ordered to appear in court and pay back the wages she had received as a member of parliament. Although reluctant and apprehensive of the confrontation, she rose to the occasion and

defiantly told them that she had nothing to be ashamed of. She spoke with pride of her record in Parliament…. “I told my interrogator…that I was a Muslim before he was born…. ‘So,’ I said, ‘Please save your breath, don’t preach to me about my religion. And don’t think for a moment I believe in this garb you’ve forced on us, as if covering myself would make me more of a Muslim.'”

“That day,” writes her daughter, “she was so excited, as if she had discovered some hidden potential.”

But it was her daughter who fulfilled that potential:

It was ironic that in the end I became what Mother wanted me to be, or what she had wanted to become: a woman content with her family and her work.

But not any work she could do in Iran. Unable to teach on her own terms, she eventually persuaded her husband to move back to the US, knowing there would be no possibility of return to Iran. She spent many anguished afternoons in her mother’s apartment, taking leave and trying to convince her to join them. Her mother was predictably intransigent. When she later fell ill, Nafisi’s grief was all the sharper for being helpless and for being mixed with guilt.

Perhaps the same could be said of her relationship with Iran. It was too late to repair either relationship: the gulf she had placed between them had, as she acknowledges, made it impossible to participate in Iran’s unfolding history or in her parents’ lives. But she had

learned that what my father had given me through his stories was a way to make a home for myself that was not dependent on geography or nationality or anything that other people can take away from me.

Yet “sometimes I caught myself looking in the mirror and seeing my mother’s face…. There she was in the mirror, not kind or generous, but cold and relentless.” The reader may ask, “Mother—or Motherland”?

This Issue

March 12, 2009