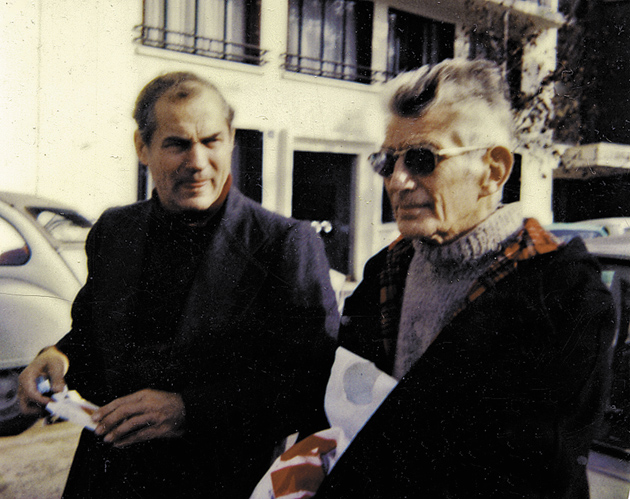

Though he followed it by a decade or more, Richard Seaver, an eminent editor, publisher, and translator, belongs to what is now thought of as a better time in American publishing, a period from, say, 1920 to 1950, during which were founded a number of houses controlled by and responding to the tastes of individuals who were concerned with the quality of what they published as much as anything else. Writers might find a place to sleep, if necessary, in their offices, and some might be given a monthly stipend. Seaver had graduated from the University of North Carolina, taught Latin at a prep school in Connecticut, and then gone to Paris to study at the Sorbonne in the years just after the war. There he edited with some friends a short-lived literary magazine called Merlin, and on his own, reading him in the original French and being overwhelmed by the simplicity and terror, discovered the early Beckett, whom he then met, published, and remained good friends with for the rest of Beckett’s life.

In 1953, toward the end of the Korean War, he was called into the navy and served as engineering officer on a cruiser. When I first met him in Paris in 1961, he still looked like a naval officer, that is to say capable and tough. I once asked him, out of curiosity, what he had known about engineering.

“Nothing,” he said simply.

He started his publishing career working at George Braziller and soon afterward went to Grove Press where he remained for eleven years, from 1959 to 1970, years of great turbulence and importance. He became editor in chief.

Grove Press was founded in 1951 and bought by Barney Rosset the same year. It began publishing European avant-garde writers and political thinkers, Beckett among them. American literature, not uniquely, had for a long time been under moral constraints as exemplified by Dreiser’s realistic novel Sister Carrie being quickly withdrawn from circulation in 1900 by Doubleday when Mrs. Doubleday found it distasteful—the heroine lived in sin with a man and then repeated the offense. Books considered obscene could not be published in or brought into the United States. This included D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, written in 1928, privately printed in Florence, Italy, and banned in England and the US. Its theme, that the individual was fully realized only when both body and mind flourished, was not sensational but its sex scenes with their candor and the use of the forbidden word “fuck” kept the book underground.

There was an invisible fault line growing, however. Six years after Lady Chatterley, Henry Miller’s remarkable Tropic of Cancer was published in Paris by the Obelisk Press. Written in the Paris of the Depression years when luxurious brothels had their own guidebooks and a dinner with wine could be bought for a dollar, it is a view from beneath the surface, seething with life, and it gradually acquired a legendary reputation. It had cachet after the war, and college girls returning from France smuggled it in hidden among their underclothes. Customs would confiscate it or worse; in the case of publishers, far worse: Jacob Brussel, who dared to publish it in New York in 1940, went to prison for ten years.

Soon after Seaver arrived, Grove Press published Lady Chatterley followed by Tropic of Cancer. They were not the first books to challenge, in whatever form, the prevailing standards, but they were the ones, along with Fanny Hill, to spearhead the court battles. The decade of cultural and sexual revolution was at hand, and the verdict of a federal appeals court that Lady Chatterley was not obscene marked a decisive moment.

A new wave swept in: William Burroughs’s Naked Lunch in 1962, Jean Genet’s Our Lady of the Flowers in 1963, Hubert Selby’s Last Exit to Brooklyn in 1964, and in 1965 The Story of O—all these as well as others not published by Grove may be said to have contributed significantly to shaping the modern sensibility toward art and sex, not to mention the books Grove published by writers like Malcolm X, Frantz Fanon, and Régis Debray. Over the years Seaver himself translated more than fifty books from French into English, including works by Marguerite Duras, André Breton, and the Marquis de Sade. Present-day painting, sculpture, and even dance would not exist without the literature that foretold them.

If only for reasons of congruity, Grove Press should have published Lolita, a book of the Olympia Press in Paris, that more than any other illustrates the power of art to overwhelm conventional ideas at least for an hour and to portray the world in another way. Lolita, fittingly, was turned down at Doubleday without even being brought to the attention of the head of the company, and was then published by Putnam’s.

Advertisement

A publisher is known by his writers, and at Grove, Viking, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, and for the last twenty years of his life at Arcade, which he founded and ran with his wife, Jeannette, Seaver’s writers were distinguished and significant, often foreign and sometimes lesser known, though they included Harold Pinter, Octavio Paz, and John Berger. There were possible Nobel laureates but modest sales.

I have a kind of Scrabble hand, the letters A A E E E I U and G L N P R, that I have never been able to make the right two words out of. They are the letters of the name Pauline Réage, listed author of L’Histoire d’O and pseudonym of the book’s actual writer, Dominique Aury, who was the mistress of Jean Paulhan and wrote the book, she told an interviewer, to hold his attention, à la Scheherazade, and give him pleasure. She wrote it lying in bed in wartime Paris, and it has a sinister and irresistible appeal from the very first lines.

The trouble is that Seaver, who translated the book into English, on several occasions told me that Dominique Aury was not the real author despite all that has been written saying so. Pauline Réage was an anagram for the name of the genuine author, a name I would recognize and know, he said. I’ve made many attempts, the first name Arlene, Eugene, Lauren, Neil, etc., but have never come up with it. Seaver was capable of having fun, but in this matter he had been straightforward and emphatic. I’m waiting for his yet-to-be-published memoir to reveal the answer.

Though he was low-key and modest, I can imagine what might be in the memoir—Brendan Behan’s riotous arrival in Seaver’s small room in Paris, dinners with Beckett, going to the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago with Jean Genet, who’d entered the country illegally, and fleeing from the anti-riot police with him, the evening of Giorgio Joyce’s death. Richard Seaver himself died unexpectedly in Manhattan this past January 5. His eighty-second birthday, celebrated by a dinner with family and friends, had taken place only a week before.

It’s hard to rank publishers. The least one can say is that there have been many changes in what is perceived as American culture and through them in his long career Richard Seaver stood for something important and inspiring that to many people seems like the real thing.

This Issue

March 12, 2009