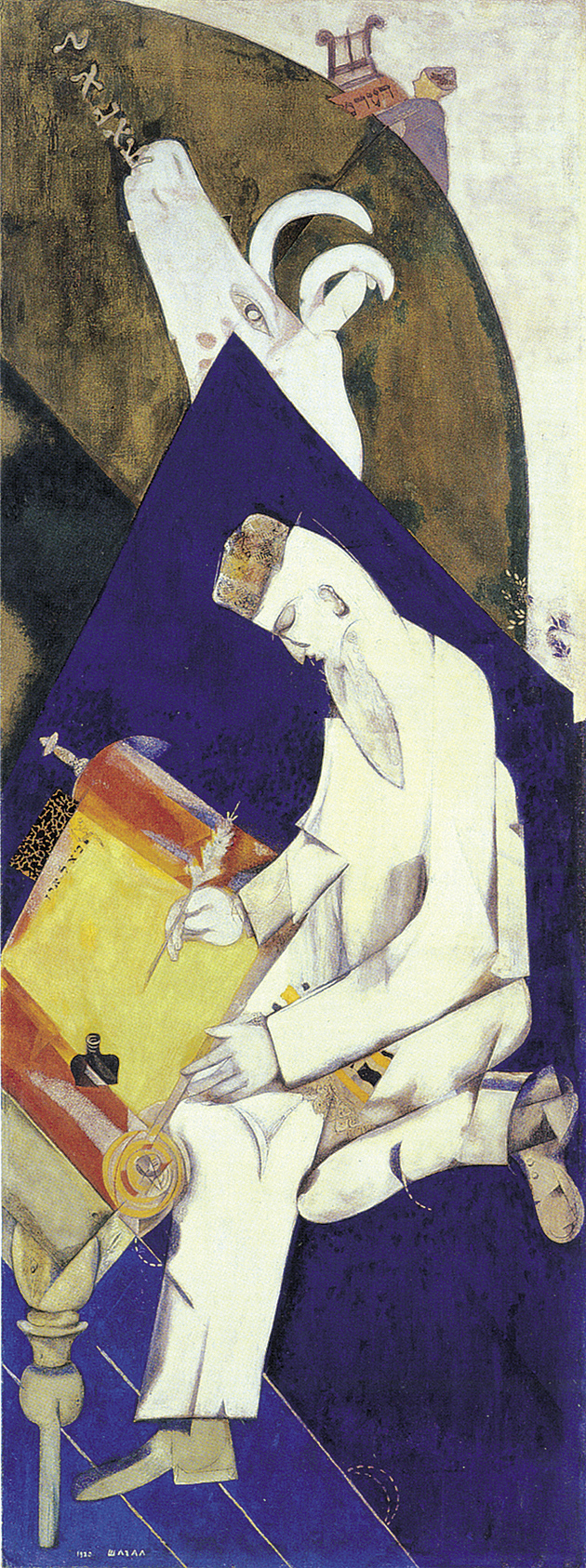

State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Marc Chagall: Introduction to the Jewish Theater (detail), 1920. This mural and the one on page 16 are from ‘Chagall and the Artists of the Russian Jewish Theater, 1919–1949,’ an exhibition on view at the Jewish Museum, New York City, through March 22. The catalog of the exhibition has just been published by the museum and Yale University Press.

1.

The painter known to the world as Marc Chagall was born Movsha (Moses) Shagal on July 7, 1887, into a poor family living on the fringes of the Russian Empire. When he died ninety-eight years later, he was the last surviving member of the School of Paris and a multimillionaire with a flat on the Quai d’Anjou in Paris and a villa in the South of France.

Swept up in the most momentous events of the twentieth century, including two world wars and the Russian Revolution, his long life was punctuated by dislocation, flight, immigration, and exile. As a young man he managed to arrive in Paris in 1911, just as the city was becoming aware of Cubism, then on his return to Russia watched the ascendancy of Suprematism, in the work of Malevich and Lissitzky. He was able smoothly to incorporate stylistic components from both of these crucial developments in twentieth-century art into his own work without becoming identified with either. He was esteemed by the Surrealists in Paris between the wars but never considered himself a Surrealist, and exhibited alongside exiled European artists in New York in the 1940s without mingling with the émigré community. In his later years he became internationally famous for his stage sets and costume designs, as well as for his decorative work in stained glass, mural painting, and ceiling decoration. His life is a gift to a biographer.

His art, though, is another story. Jackie Wullschlager’s substantial biography draws on a wealth of unpublished letters still in the possession of his descendants to tell the story of Chagall’s journey from shtetl to château. But not for an instant did it convince me that Chagall was a great or even an important artist. He himself believed that by the time of his final departure from Russia in 1922 his best work was behind him, even though he was to live for another sixty-three years. But is there really all that much to respect even in the early paintings? What, finally, did he contribute to the history of twentieth-century art? The more I read about Chagall the artist, the less original his paintings looked, though I must add that the author’s descriptions of his theater and ballet designs rekindled the admiration I have long felt for his work for the stage.

The opening chapters vividly evoke the world of Chagall’s boyhood in Vitebsk, which lay within the Pale of Settlement, the area of western Russia to which Catherine the Great had confined the Jews living in her empire. He was the eldest of nine children born to Yiddish-speaking followers of the Hasidic sect; his parents were poor but not impoverished. Khatskel, his father, hauled crates in a herring warehouse on the banks of the Dvina River; his illiterate mother, Feiga-Ita, ran a successful business selling provisions from home.

Vitebsk (today in Belarus) was a town of rickety wooden dwellings, public bathhouses, unpaved streets, onion-domed churches, and more than sixty synagogues. On the poor side of town every householder kept goats, chickens, and a cow in the yard. Rabbis, Talmudic scholars, matchmakers, musicians, and elderly Jewish peddlers who could be seen wandering from town to town with sacks on their backs: the sights and sounds of Chagall’s childhood would become the subject of his art.

Although he ceased to practice religion at the age of thirteen, Chagall’s work is suffused with imagery drawn from Jewish ritual and folklore, particularly from Hasidic festivals and feast days when song and dance were used to express the mystical union of man and nature. Through the joy of Hasidism, his biographer believes, he “transformed the cramped, dull back-streets of his childhood” into a color-saturated “vision of beauty and harmony on canvas.”

The transformative dimension of Chagall’s work is lost to us today, but it is precisely what so impressed his contemporaries. The artist and critic Alexandre Benois, for example, was amazed that a dirty, smelly “Jewish hole” like Vitebsk with “its winding streets, its blind houses and its ugly people, bowed down by poverty, [could] be thus attired in charm, poetry and beauty in the eyes of the painter.”

When Chagall’s ambitious mother bribed a teacher at the local school to ignore the quota on Jewish pupils, she put her son on the long road out of Vitebsk, and eventually out of Russia—not least because the boy, who until then spoke only Yiddish and wrote in Hebrew, was taught Russian and made to use the Cyrillic alphabet. He left school in 1905 without a diploma, but by then he had become obsessed with drawing and determined to become an artist.

Advertisement

Such an activity was unimaginable in a world with no pictorial culture of any kind. “In our home town,” he wrote, “we never had a single picture, print or reproduction, at most a couple of photographs of members of my family…. I never had occasion to see, in Vitebsk, such a thing as a drawing.” When a classmate saw paintings by the teenage Chagall, he blurted out that his friend was “a real artist!” Chagall claimed that he had never heard the word “artist” and did not know what it meant.

All the more remarkable then that his mother managed to enroll him in the only art school in the whole of the Pale of Settlement, the academy in Vitebsk run by a Jewish portrait and genre painter who had studied at the St. Petersburg Academy. Thanks to the solid, traditional techniques taught by Yuri Pen, Chagall learned to draw from plaster casts and to work from a life model. And although he was to reject Pen’s realistic style of painting, he learned from his teacher’s example to find his subjects in shtetl life all around him. In time, Chagall would reconfigure the sights and sounds of his childhood as helium-filled fantasies in which cows sail through the night sky and fiddlers fiddle on roofs. But to do so he had to leave Vitebsk. As Wullschlager shrewdly comments, “Chagall’s art was fuelled by the twin drives to escape and to remember.”

At age nineteen Chagall moved to St. Petersburg, where at last he could see the work of the old masters in the Hermitage, immerse himself in the theater, and form friendships with other artists, writers, and patrons. But he painted the works of his first maturity, Birth, Russian Wedding, and The Dead Man, between 1909 and 1911 not in St. Petersburg but during long stays back home in Vitebsk, as though he needed to reconnect with his Jewish roots before venturing into the unknown milieus of the avant-garde. What makes these pictures modern is Chagall’s crude, childlike rendering of heavily outlined figures and buildings, an early instance of his use of expressive distortion that Wullschlager links to the expressionist theater productions he had just seen in St. Petersburg. To find inspiration in “primitive” (peasant and folk) art was not in itself particularly unusual among progressive artists at this date, but the Jewish themes and the notes of absurdist whimsy are very much Chagall’s own.

2.

Russian art around 1900 feels suspended in a lingering Symbolist twilight, embodied in the work of the World of Art group of painters. Promoted by impresario Sergei Diaghilev, these aesthetes alternated between art nouveau decadence and eighteenth-century nostalgia. Benois, Léon Bakst, and their colleagues preferred painting in watercolor to painting in oil, and scenography or mural painting to working on canvas. Though Chagall tended to dismiss the World of Art painters as aristocratic and effete, on his return to St. Petersburg in 1909 he enrolled in the school where the most famous of them taught.

The lush sets and costumes Bakst was then designing for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes set a gray world alight. His palette of hot oranges, shocking pinks, and boiling ultramarines perfectly suited the bold, Slavic rhythms of Igor Stravinsky’s music and Michel Fokine’s choreography. The last and most sensuous Orientalist of all, Bakst electrified audiences in Paris and London with the exotic costumes and sets he designed for Scheherazade, the ballet with the plot once described as “an orgy followed by a massacre” in which half-naked slaves and harem girls writhed and expired against backdrops painted in colors of unearthly intensity.

Chagall studied with Bakst only for six months, but it was Bakst who set the young artist’s imagination free by cautioning him against refinement and encouraging him to simplify his form and liberate his brushwork. Above all, he taught Chagall about color. “I have a taste for intense colour,” Bakst said, “and I have tried to achieve a harmonious effect by using colours which contrast with each other rather than a collection of colours which go together….” For this, Chagall was grateful. “My fate was decided by the School of Bakst…. Bakst changed my life. I will never forget that man.” And because Bakst had moved to Paris to work with Diaghilev in the spring of 1910, a year later the twenty-three-year-old Chagall followed.

In May 1911, with the financial support of an early patron, Marc Chagall made the four-day train journey from Russia to Paris. Speaking no French and knowing only a handful of Russians, he was nevertheless enchanted with the city. “I seemed to be discovering light, colour, freedom, the sun, the joy of living, for the first time.” A few days after reaching Paris he made his way to that year’s Salon des Indépendants to see the Cubists all Paris was talking about. Only it wasn’t the work of Picasso and Braque that hung in Room 41 of the salon that year, but the “Salon Cubists”—Henri Le Fauconnier, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, and Robert Delaunay.

Advertisement

Chagall understood instinctively that to become a modern artist he had to abandon traditional perspective, foreshortening, and modeling, and assimilate the fractured geometrical planes and shifting perspectives of Cubism into his work. But at that stage in his life, he could not have known that he was looking at feeble imitations of Cubism, not the real thing. He took Gleizes as his model and enrolled in the school where Le Fauconnier and Metzinger taught.

This is where I part company with Wullschlager, who sees more significance in the work of Chagall’s first French period than I think it merits. In pictures like I and the Village (1912; Museum of Modern Art, New York) or The Cattle Dealer (1912; Kunstmuseum, Basel), faceted planes are used not to create volume or to explore pictorial space but as mannerisms or stylistic tricks to give the flying fiddlers, farmyard animals, and upside-down figures a veneer of modernism. Sure, Chagall added the brash color and fairy-tale imagery, but ultimately these pictures, like Le Fauconnier’s, are pastiche Cubism—in Chagall’s case, an imitation of an imitation. To say as Wullschlager does that Chagall contributed to the history of modern art “an expressive, mystic sensibility that challenged the form-conscious rationalism of Western art” is to admit that what is original about his work is what he painted, not how.

Compare Chagall’s two versions of Birth—the first painted in Vitebsk in 1910, the second in Paris in 1911. In the first version, the setting is a wooden shtetl house painted in a somber palette of muddy red, sour yellow, and brown. Linear perspective leads the eye to the triangle formed by dark red bed curtains parted to reveal a naked mother lying on bloodstained sheets, a grim midwife holding a newborn child, and a father cowering under the bed, while in the background neighbors and a rabbi look in at the window and push through the door.

The Cubist version is painted in harsh primary colors. Now the blood-soaked mother is only one focus of attention in a much more diffused and brightly colored composition. Chagall opens up the closed interior by turning the walls and floor into flat geometric planes, so that our eye zigzags in and out of space as though we were looking at a picture painted on a folding screen. But by scattering a dozen or more tiny figures across the canvas, he dissipates the picture’s pictorial cohesion and dramatic impact. Now the roof seems to have come off, and the house has morphed into a fairground or circus where figures tumble from the sky and farm animals sit down to dinner.

But to what purpose? Cubism isn’t particularly suited to narrative or genre, but Chagall doesn’t yet know this. What is more, in their Cubist paintings Picasso and Braque effaced their own personalities and tended to avoid the direct expression of emotion or autobiography. Intense feeling, if it appears in a “true” Cubist portrait or still life, is expressed obliquely, embedded in the very texture of the picture. Chagall’s version of Cubism could almost be called the polar opposite of the real thing.

Both versions of Birth show that the arrival of a child in a poor Jewish household was a semipublic event accompanied by community ritual and rejoicing. But the brutal 1910 version of Birth is the more coherent and, for me, therefore, the more powerful. Here is Wullschlager’s commentary on the Cubist version of the picture:

This is birth as psychological reality: the sense of the indissolubility of life and death, and that for each individual woman birth is at once miracle, symbol of hope, and frightening physical ordeal.

As criticism this isn’t helpful because, as so often when Chagall’s admirers write about his work, it focuses on the subject, not the handling of color, line, draftsmanship, composition, space, and so forth.

Why, then, did discriminating critics like Apollinaire and Blaise Cendrars write with such appreciation about Chagall? One answer is that Chagall timed his arrival in Paris perfectly. The Ballets Russes’ productions of Scheherazade and The Firebird had just enthralled Parisians, who were experi- encing a craze for all things Slavic. Chagall’s pictures, Wullschlager writes, “looked like strange, exotic intruders into Parisian art.” To this observation I would reply, “exactly”—this is what blinded his contemporaries to their crude constructions, heavy attempts at humor, cringe-making whimsy, and fundamental lack of originality. Then too, both these critics wrote loyally about Chagall’s paintings but they rarely said anything penetrating or significant about them. To Apollinaire, for example, Chagall is “an extremely varied artist, capable of painting monumental pictures, and he is not inhibited by any system.”

The same critic used the word “surnaturel” to describe Chagall’s work, but Chagall didn’t know what it meant, and I must admit that as applied to Chagall’s paintings, which have nothing to do with the exploration of the unconscious, neither do I. Beginning in 1913 Chagall built up a devoted following in Germany, where collectors saw his color-drenched fantasies and use of distortion as having something in common with Expressionism. But if one compares Ludwig Kirchner’s Berlin street scenes with Chagall’s nostalgic fantasies of life in the old country, it is hard to understand why.

In June 1914 Chagall returned to Russia for what he thought would be a three-week visit and found himself trapped by the outbreak of war. Instantly the hard-edged Cubism of the first Parisian period vanished in favor of a softer and more integrated style sometimes described as Cubo-Futurism. In pictures like the monumental Jew in Red (1914), it is as though the fragmentation of form that characterized the Cubist phase had simply never happened. And soon enough, a new stylistic mannerism appeared that enabled Chagall to fill the void left by Cubism.

As revolutionary fervor mounted in the years 1915–1917, Kazimir Malevich’s first Suprematist paintings brought art closer to abstraction than it had ever come before. The fierce purity of Malevich’s geometric designs in black, white, and unmixed primary colors perfectly expressed the radical impulse to symbolically wipe the social slate clean by eliminating representation of any kind. Ultimately this Lenin among artists would paint the series of white squares on white grounds that are among the most influential works of the twentieth century. “I say to all,” wrote Malevich,

Abandon love, abandon aestheticism, abandon the baggage of wisdom, for in the new culture, your wisdom is ridiculous and insignificant. We, suprematists, throw open the way for you.

The power of Suprematism lay in its elimination of individuality, of expression, of memory, and of the past.

Just as Chagall had arrived in Paris on the crest of the first wave of Cubism, so now he returned to Russia as Suprematism swept the old art away. The difference was that this time the new art movement made his folksy imagery—indeed imagery of any kind—instantly passé. And just as he had assimilated Cubist form without, I think, necessarily understanding it, so now he appropriated Suprematist style without having the slightest idea that for Malevich abstraction was a means toward the elimination of the self in order to achieve a higher level of spiritual experience.

Chagall wasn’t an explorer and he wasn’t an intellectual. In The Apparition (Self-Portrait with Muse) of 1917–1918 he adds Suprematist circles of silver and blue to what is basically a traditional Annunciation, with Chagall taking the place of the Virgin Mary and substituting a figure representing his personal muse for the Angel Gabriel. The glad tiding the angel brings to the painter is the arrival of a new art inspired by the Russian Revolution. Chagall takes circular forms that in Malevich signify spiritual transcendence and turns them into the angel’s feathered wings. Where Malevich pares down, Chagall fills the background with the paraphernalia of the artist’s studio. The effect is certainly decorative—all cloudy blue-gray curlicues and shimmering white disks—but it is hard not to feel that Chagall has taken something profound and searching in Malevich and turned it into stylistic embellishment. And it is almost endearing to see that, far from aspiring to subsume his identity into the whole, Chagall here sees the entire Russian Revolution from the perspective of how it will affect his work.

At the beginning of the Revolution the avant-garde actively worked with the government. Chagall prospered under the Bolsheviks. In 1918 the state bought ten of his paintings and appointed him commissioner of arts for Vitebsk. The following year he became director of the Vitebsk’s People’s Art College. By the spring of 1919, however, he had begun to realize that the individualism and egotism of his art was anathema to Bolshevist thought. The sculptor El Lissitzky, an infinitely more committed and ideologically driven revolutionary than Chagall, brought the ranting Malevich to the school as a professor. Malevich and Lissitzky then set about turning it into a stronghold of Suprematism. Using time-honored tactics of the far left, their first step was to denounce Chagall’s art as bourgeois and decadent. Next they took over the school, firing the entire staff, rechristening it the “Suprematist Academy,” and terrorizing the students into accepting their collectivist aesthetic. In a foretaste of what would happen to artists and intellectuals under Stalin, the Chagall family was given twenty-four hours to vacate the rooms they occupied in the school. In June 1920 Chagall left Vitebsk for Moscow with his wife Berta (later Bella) and infant daughter Ida. He was penniless.

Yet again Chagall’s timing was miraculous. One of the characteristics of progressive Russian art at this time was its close association with the stage. Just as Chagall arrived in Moscow, the impresario Aleksai Granovsky brought his Yiddish Chamber Theater, a modernist company specializing in radical productions of Yiddish plays, to the city. At once he commissioned Chagall to work on the sets, backdrops, and costumes for an evening of three plays about shtetl life by the classic Yiddish author Sholem Aleichem. In the last months of 1920 Chagall locked himself in the auditorium of the theater for forty days to paint the murals that are now universally regarded as his greatest artistic achievement. These theater murals are on view in an exhibition devoted to the Russian Jewish theater at the Jewish Museum in New York City until March 22.*

There are seven in all—including four large upright panels depicting the archetypal Jewish characters of the folk musician, the wedding jester, the Torah Scribe, and the wedding dancer, who also symbolize the arts of music, drama, literature, and dance. These paintings are unlike anything Chagall had done before because they combine monumental scale with simplified form. Realizing that the audience needed to take them in from a distance and also that they should not compete with the stage sets, he seeks clarity in the composition and suppresses extraneous decoration.

For the first time, Chagall now used the whole stage as his canvas. As Wullschlager explains:

When the curtain, decorated with goats, rose on the first night, the audience gasped at the eerie effect by which the actors, painted by Chagall and moving in exaggerated staccato bursts…, looked identical to the portraits of them in the largest mural: both were Chagall’s creations, the only difference being that the live ones spoke, the painted ones stayed silent. The theatrical effect was utterly original…. The audience came as much to be perplexed by this amazing cycle of Jewish frescoes as to see Sholem Aleichem’s skits…. Ultimately, the [evening] was conducted, as it were, in the form of Chagall’s paintings come to life.

And here, I think, we come to the one aspect of the visual arts where it is possible to speak of Chagall’s genius. He is a stage designer comparable to Bakst in the way he uses radiant color and fantastic costumes as thrilling complements to music and dance. Though the Moscow Yiddish Theater never employed him again, and in the 1930s the French never appreciated (or perhaps never realized) that they had a designer of such talent living in Paris, he came into his own in the 1940s when he was living in New York and Léonide Massine commissioned him to design the scenery and costumes for the New York Ballet Theater’s new production of the romantic ballet Aleko, based on the Pushkin poem with music by Tchaikovsky. Once again, he painted the costumes and sets by hand to create a spectacle the dance critic Edwin Denby considered far more interesting than the music or the choreography. Wullschlager writes:

From now until the end of his life, Chagall would be irresistibly drawn to a stage, a ceiling, a wall, a cathedral window…. In America,…he embraced the large scale as the new country reawakened possibilities, dormant since Moscow’s murals, that would shape the rest of his career.

One of the joys of my own childhood was the Metropolitan Opera’s production of The Magic Flute with sets and costumes by Chagall. Though I don’t share Wullschlager’s enthusiasm for his later murals for the Paris Opera and the foyer of the Metropolitan Opera at Lincoln Center (more soft-focus, blowsy sentimentality), in this, at least, we agree.

Unlike his enemy Malevich, Chagall got out of Russia with his wife and daughter, arriving via Berlin in Paris in the summer of 1923. The numerous flower and circus paintings of the next decade and the illustrations for Dead Souls, The Fables of La Fontaine, and the Bible, which he worked on throughout the 1930s, are visually appealing, but ultimately they feel unimportant. In them you have no sense that Chagall is breaking new ground or attempting to renew his sources of inspiration.

The story of Chagall’s escape from Vichy France in April 1941 with the help of the determined young American diplomat Varian Fry could have been lifted from the script of Casablanca, and Wullschlager tells it so well that you can’t wait to see what’s going to happen next. And she adds a coda. Twenty years later, when Fry asked all the artists he had helped during the war each to donate a lithograph to be published in a book that would be sold for charity, Chagall alone refused, only finally donating a work after Fry’s death. That Wullschlager bothers to tell this story is in itself an indication of her growing disillusionment with her subject.

With the death in 1944 of his remarkable first wife, Bella, whose loving and stabilizing presence fostered Chagall’s creativity, we can add his name to twentieth-century art’s roll call of egotistical monsters. Bella’s successor, Chagall’s British-born companion Virginia Haggard, would leave him, but not before he had beaten her to the ground with his fists. Within days, Chagall found the woman who was to be his second wife, the dreadful but canny Valentina (Vava) Brodsky. With Vava in charge of his sales, Chagall became a rich man, but also an object of contempt to both Picasso and Matisse, his neighbors in the South of France. Wullschlager tells this fascinating story with unflagging verve. Her impeccable research brings into focus the colorful cast of supporting characters with whom he shared the dramatic upheavals of his life. But I don’t think his art deserves a biography this good.

-

*

”Chagall and the Artists of the Russian Jewish Theater, 1919–1949,” the Jewish Museum, New York City, November 9, 2008–March 22, 2009; and the Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco, April 25–September 7, 2009. The catalog, by Susan Tumarkin Goodman and with essays by Zvi Gitelman, Benjamin Harshav, Vladislav Ivanov, and Jeffrey Veidlinger, is published by the museum and Yale University Press.

↩