1.

Professor Cass Sunstein of the Harvard Law School, who is among the most prominent and influential American academic lawyers, appears on many lists of potential nominees to the Supreme Court and it is therefore opportune that he has published a new book exploring constitutional philosophy. He is a breathtakingly prolific writer on a variety of subjects including constitutional and administrative law and the impact of behavioral psychology and economics on law. He was a colleague of President Barack Obama at the University of Chicago Law School and remains a friend; Obama consulted him on constitutional questions during the election campaign and has now appointed him administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs.

President George W. Bush’s two Supreme Court appointees—Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito—refused to discuss their own philosophies during their very unsatisfactory Senate confirmation hearings; they evaded all such questions by insisting that they could interpret and apply the Constitution without imposing their own conservative convictions about political morality.1 Sunstein rightly rejects that claim as absurd. “There is nothing,” he says, “that interpretation just is.” Every interpretive strategy is grounded in some assumption of political morality about the kind of constitution America should have.

Sunstein’s book offers few unqualified judgments about how the most controversial constitutional issues should now be decided. However, he does state his views of some of the Supreme Court’s decisions clearly enough to indicate his own inclinations. He suggests, for example, that the Court was right to avoid forcing states to permit racially mixed marriages in the 1950s; that it ruled too “broadly” in declaring abortion rights in Roe v. Wade, but that its decision is nevertheless by now too much part of our constitutional traditions to justify overruling it; that the Court’s recent ruling declaring that the Second Amendment entitles private citizens to own guns was “respectable” and is supported by a sensibly uncritical “traditionalism.” He is sympathetic to those who argue that the Court should not now require states to accept same-sex marriages, and that it should not declare the reference to God in the Pledge of Allegiance unconstitutional.

On one controversial issue he is more explicit. Justices and lawyers now disagree about whether it is right for the Court to refer to foreign judgments in its opinions, as Justices Anthony Kennedy and John Paul Stevens have done, for instance, in opinions striking down antisodomy laws and the execution of mentally retarded people. Roberts and Alito both opposed the practice in their nomination hearings and Sunstein joins them in that view because on balance, he says, referring to other countries’ conclusions will not improve our own.

Sunstein offers a persuasive general account of constitutional interpretation. He insists that a strategy of adjudication must be judged by its consequences but he concedes that justices need a further theory, beyond that pragmatism, to decide what consequences are good, and that they inevitably disagree about that further theory. He is drawn to what he calls a “perfectionist” account of how the Supreme Court should decide its cases. The justices must not invent a new constitution or ignore their own constitution’s history even if they think a new constitution or a different history would be better. They must reject any interpretation of a constitutional provision that does not adequately “fit” the text or history. But that constraint, he insists, often leaves different interpretations eligible because they all fit well enough, and justices must then choose among these by selecting the interpretation that they believe best by the standards of political morality—the interpretation that makes the Constitution, as he puts it, morally “as good as it can possibly be.”

Most of his book describes and assesses different interpretive strategies. Each must be judged by asking: In what circumstances and on what assumptions would following that strategy make the Constitution as good as it can be? The most natural strategy, given that goal, would require judges to write opinions stating what they take to be the most attractive conceptions of equality, liberty, and democracy that fit the Constitution’s text and history and then apply those conceptions to the cases before them. Sunstein cites some former justices—William Brennan and Thurgood Marshall—as apostles of this approach and calls them “visionaries.”

But he explores at greater length more modest interpretive styles that show greater deference to constitutional traditions established over many years by many people expressing their own opinions about moral and political issues. He refers to these traditions, taken together, as “a constitution of many minds” and suggests that showing more respect for that traditional constitution might constitute a “second- order” perfectionism that makes the Constitution as good as it can be in carefully limited rather than theoretically bold steps. He calls that more modest approach “minimalism”: minimalists, he says, like to decide constitutional cases “unambitiously,” through “incompletely theorized” arguments that deploy intellectually “shallow” justifications that do not appeal to any “deep” theories about liberty or equality or the proper limits of executive power.

Advertisement

He distinguishes two versions of minimalism. “Burkean” minimalists embrace tradition uncritically because they believe history has achieved a kind of wisdom, slowly over many years, that contemporary critics might be unable to appreciate. Some justices have adopted that form of minimalism in due process cases: they refuse to declare any form of government regulation an unconstitutional infringement of liberty if—like the prohibition against doctor-assisted suicide—that regulation is long established.2

Sunstein himself prefers what he calls “rationalist” minimalism, which asks “whether long-standing practices are actually based on sense and good faith, or instead on nonsense and prejudice.” (On the present court, he says, Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer are rationalist minimalists.) He is more cautious in endorsing minimalism as a general strategy than he once was.3 He describes its defects and allows that in some circumstances—when justices are very confident, for instance—a more “visionary” approach might be better because “judges should sometimes attempt a degree of depth, and need not always struggle to root their decisions in what other people already think.” He is mainly concerned, however, not to endorse any strategy but to notice the virtues and vices of each and describe the highly artificial circumstances in which each would be ideal.

2.

Minimalism has long been popular on the Supreme Court: justices are fond of saying, as Roberts did recently, that “if it is not necessary to decide more to dispose of a case, in my view it is necessary not to decide more.”4 Sometimes minimal opinions that cite no broad principles are necessary for institutional reasons: when justices disagree in complex ways and no one theoretical statement of the issues would command a majority or even plurality of them. But conventional wisdom now disapproves of broad opinions even when they are possible. Minimalism often has serious costs, however, particularly when important constitutional rights are at stake, and Sunstein’s book provides a good opportunity to explore these.

The Supreme Court has two roles in American government: it is both a court of law, charged with protecting the constitutional rights of individual citizens, and also a constitutional architect whose decisions change the country’s history and affect the lives not just of those whose rights it protects but of the rest of the nation as well. From time to time these roles appear to conflict. They do so when justices believe that the Constitution, properly interpreted, grants rights that have not been recognized before and whose judicial enforcement would outrage a great many citizens. Justices face that conflict when they are first persuaded that some well-established legal practice actually violates constitutional rights and must be stopped.

Such established but constitutionally questioned practices have included segregating public schools by race, allowing prayer in public schools, forbidding mixed-race marriages, capital punishment, and failing to recognize same-sex marriages. Judges acting as wise constitutional architects are likely to have grave misgivings about altering such practices—or at least about altering them altogether at once rather than initially only in special, narrowly defined circumstances. They would prefer to use what Professor Alexander Bickel called “the passive virtues” in exercising the Court’s discretion to choose among the challenges to such laws that it agrees to consider. Before the Court finally decided to ban antimiscegenation statutes in 1967, it twice declined opportunities to do so, even though it had become apparent that a majority of the justices thought such statutes unconstitutional. For over a decade parties to mixed marriages were jailed for exercising what a majority believed were their constitutional rights.

Sunstein does not think that justices should decline to rule on unjust but popular practices, except in what he calls “rare but important” cases (like, presumably, miscegenation in the 1950s) when judicial revolution might provoke a serious and even violent backlash. He seems to prefer a more nuanced kind of minimalism in which courts are able to reach just results in the cases they consider but on “narrow” grounds defended with only “shallow” arguments.

For example, the Court might hold only that states must accord same-sex couples the tax and other benefits of marriage without declaring that they must allow such couples the status of marriage itself. Faced with demands for broad abortion rights, the Court might have contrived to take first a case that would allow it to strike down abortion prohibitions on narrower grounds; it might, for instance, have outlawed prohibitions that threaten the health of pregnant women. These strategies would allow the Court to make progress toward justice without what Sunstein calls “theoretically ambitious claims about the nature of ‘liberty’ under the due process clause, or the ideal of equality under the equal protection clause.”

Advertisement

Minimalism would permit the Court to develop doctrine slowly, responding to experience and public discussion in expanding or contracting its rulings later. It would allow public opinion to mature through continuing debate and experimentation in state and local politics, perhaps crystallizing emerging political trends that would allow the Court to rule more generously later with fewer social costs. Constitutional architects must think in the long term and with due attention to the timing, costs, and dislocations of their rulings.

Nevertheless a justice who embraced this nuanced minimalism instead of seeking the earliest opportunity to give his constitutional convictions their full force would, it seems to me, have failed in his other duty: not as an architect of the Constitution but as a guardian of the rights it protects. His strategic delay would have permitted thousands of citizens to be irreparably damaged because they were denied—unconstitutionally in his view—the right to control their own reproduction or the opportunity to marry someone they love of a different race or the same sex.

3.

Is this conflict between constitutional statesmanship and conscience inevitable? Sunstein explores what might seem to be a way out. Perhaps justices who form an untraditional view about what the Constitution requires should, he suggests, accept, in all humility, that the traditions they challenge actually reflect a more accurate view of what basic moral and political rights a constitution should recognize.

Here Sunstein considers the work of the Marquis de Condorcet, the eighteenth-century mathematician and political scientist, who has recently attracted much attention among political scientists. Condorcet proved that, given the assumption that each individual in a particular group is more than 50 percent likely to be correct about some matter, the view of the majority of that group is more likely to be correct than that of any minority within it, and the larger the group the more likely is its majority to be correct. If the Condorcet Jury Theorem (as it is called) is applicable to constitutional tradition, then it might license justices to think that the constitution of many minds—what generations of politicians and citizens have thought the constitution to be—is more likely to be a sound statement of basic rights than what a few of them, however thoughtful, would substitute.

Sunstein notes certain qualifications to the Condorcet theorem. It does not hold when a majority’s views reflect bias or a herd instinct and so would not warrant deferring to traditions of racial prejudice or sexual discrimination. But he flirts with the idea that in other cases—about gun rights, abortion rights, or assisted suicide, for instance, or whether a president is permitted to initiate certain military actions without congressional approval—judges might legitimately be tempted by the Condorcet theorem to think that tradition embodies more constitutional wisdom than is available to them alone.

It is extremely doubtful, however, that Condorcet’s theorem has any application at all to moral issues. The crucial assumption on which his proof depends—that any individual in a specified group is more likely than not to make a correct judgment—is indeed plausible when the question is a matter of straightforward fact and perception: when a group of eyewitnesses is asked the color of a getaway car, for example. The best explanation of how such people make such judgments—by seeing the car—makes it much more likely than not that any person of normal vision in the right position would make the right judgment. The assumption may also hold with respect to other matters of fact and of logic: guesses about the weight of an ox, or informal weather predictions, or the solution of not-very-difficult mathematical puzzles, for instance.5 But nothing in any plausible explanation of how people form moral convictions—which are not a matter of perception or logic—provides the slightest ground for assuming that people generally are more likely than not to form correct convictions about controversial moral issues; and history hardly supports that hypothesis either.

So the conflict between the two roles of constitutional judges remains. Some lawyers try to resolve it in a different way: by supposing that in a democracy controversies about the most basic political issues should be decided by the people, not judges. If some legal practice has been long established, it should be changed only by a fresh decision of democratically elected legislators, not unelected judges. That is a popular argument but a weak one. As Sunstein observes, it begs the question by assuming that democracy, properly understood, means only government by the will of the majority from time to time. The Constitution plainly assumes a different conception of democracy: a partnership in self-government in which majority rule is deemed fair only if the basic rights of all citizens are protected. If a justice assumes that the right to be treated as an equal in matters of race or sexual preference is among these democratic preconditions, then he protects rather than subverts democracy by enforcing that right.

Other constitutional lawyers deny that the Constitution, properly understood, grants anyone any rights at all. The task of constitutional judges, they think, is essentially political: their only legitimate function is to produce a constitutional structure that works efficiently for the nation as a whole. So no woman has a right to abortion so long as it would not be wise constitutional statesmanship to grant women that right. That seems, in fact, to be the inarticulate and perhaps unselfconscious assumption of many constitutional theorists: they speak approvingly about the Court’s political strategy in deciding which cases to decide and how broadly or narrowly to rule, with no attention to the lives of citizens whose needs and rights might contradict that strategy. But Sunstein is not skeptical about constitutional rights: he believes that constitutional theories must be judged by their consequences but he insists that what counts most, in assessing these consequences, is how far the strategies correctly identify and protect the constitutional rights that make the Constitution as good as it can be.

He does suggest, quite independently of any reliance on Condorcet’s theorem, that judges should not attempt large statements of principle because they are not necessarily competent to do so and because “shallowness is less error-prone.” True, justices have limitations. But once we set aside the idea inspired by Condorcet, that the legal or moral opinions of large numbers of people are more likely to be sound than those of a few, it is unclear what conclusion we should draw. What group of politicians or citizens is better equipped to discern constitutional rights, as a group, than justices are?

In the end, moreover, the justices must inevitably make difficult and essentially controversial judgments for themselves. They cannot decide whether the consequences of a series of narrow and shallow decisions about abortion are likely to be better, in the long run, than an immediate comprehensive analysis of the problem without first deciding whether women do have an unqualified constitutional right to an early abortion. They cannot decide whether a series of narrow decisions is more likely to reveal the correct answer to that latter question without deciding philosophical issues about the nature of truth that are at least as difficult as the questions minimalists say they are not competent to answer.

Nor does the Court’s history demonstrate that justices make fewer errors when they decide as narrowly as possible. A decision that seems right or politically tempting when justices limit their attention to the facts of a particular case may nevertheless be wrong because it cannot be supported by any more principled justification that fits other cases. The most glaring example is the Court’s shameful 2000 decision in Bush v. Gore ; the majority was careful to claim that it was endorsing no general principle in making Bush president.6

But there are other, more instructive examples. Sunstein and others cite the infamous 1905 Lochner decision—the Supreme Court struck down a New York state law limiting the number of hours a baker is permitted to work—to illustrate the risks of deciding cases on broad grounds of general principle. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, in his famous dissenting opinion in that case, declared that the Constitution “does not enact Mr. Herbert Spencer’s Social Statics,” suggesting that the Court had based its decision on some explicit philosophical theory.

But Holmes was just showing off. Justice Rufus Peckham’s majority opinion, though disastrous in its implications and consequences, was in many ways a model of shallow argument. He accepted that the American states enjoy a general “police power” to limit liberty for proper objectives including protecting the general welfare. He refused to offer any general account of the limits of that power, conceding that the Court had upheld restrictions on economic freedom in other cases involving, for instance, limits of working hours for miners. He declared those other cases different from the case before him and recognized that the Court should not normally substitute its judgment of legislative policy for that of state legislatures.

He then announced a ruling based on undefended assumptions about the health of a baker’s life compared to that of other occupations and made a flat, question-begging, and counterintuitive declaration that economic regulation like working-hour limits has no effect on the general public’s welfare. If he had tried to state a general principle identifying the kinds of liberty that the Fourteenth Amendment protects, and explaining why those liberties deserve special constitutional protection, his opinion would have been much harder to write. Among other difficulties he would have had to distinguish or confront the many cases cited in Holmes’s and Justice John Harlan’s dissents— involving usury, stock sales on margin, lotteries, and Sunday working laws, for example—in which the Court had approved economic regulation.

Holmes’s and Harlan’s dissenting opinions, on the contrary, were theoretically much more ambitious. Harlan laid down a general political theory about the proper distribution of power between legislature and courts very much like the one the Court finally adopted after several further decades of bad constitutional law and much consequent suffering.

There are many more recent examples of decisions in which an initially more ambitious and more adequately theorized statement of relevant principle would probably have improved the law. In 1976 the Court held that limits on candidates’ campaign expenditures violate free speech. Its decision was sweeping, but its justification was theoretically very modest: it said only that limitations of expenditures mean limits on the political speech that can be broadcast, and that political speech is at the heart of the First Amendment. Any more thorough examination of the reasons for protecting political speech might well have revealed the weakness of that argument: if the central point of free speech is to protect democracy, expenditure limits would have furthered, not hindered, that point.7

The Court’s recent decisions about the constitutional rights of “enemy combatants” detained indefinitely provide other examples. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s initial 2004 decision, in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, carefully limited its holding that detainees have constitutional rights to American citizens. Much pointless legislative maneuvering and much unjust suffering would have been avoided if the Court had anticipated the decision it finally made four years later in the Boumedienne case: that the alien detainees held in Guantánamo have constitutional rights as well.8

I must not overstate the case: there often are good reasons for judges limiting the issues they take themselves to be deciding in any particular case. The briefs of litigants and interest groups are likely to have concentrated only on narrow issues, for example. But aggressive judicial modesty—insisting on deciding no more than is absolutely necessary to dispose of the case at hand and making no attempt to ground decisions in larger principles—has become too mechanical and too uncritical a strategy. It often generates the injustice I have described. It also permits justices to avoid full intellectual responsibility for their decisions. Sunstein says that Roberts and Alito “appear” to be minimalists. But they have several times joined with the other conservative justices to overrule past doctrine by stealth, writing shallow opinions whose radical force could not have been disguised if they had attempted to justify their decisions in larger principle.9

Worse, aggressive modesty erodes the legitimacy of the Court itself. It cannot claim to represent the will of the people. It can find its moral authority only in the character of the reasons it offers for its decisions.10 It has a sovereign responsibility to show that its judgments are grounded in principles that can responsibly be claimed to be premises of America’s democracy. Of course justices should not try to rewrite Locke’s Treatise on Government or The Federalist Papers in every opinion. But they must say enough, in important and controversial decisions about constitutional rights, to indicate the principled basis of their decision and show that they understand and accept at least the obvious further commitments those principles require.

It is often said that ambitious judicial judgments are arrogant. Close to the opposite is true: it is arrogant for unelected officials to declare or deny fundamental rights with no or little attempt to state a warrant for their decision in broad constitutional principle. Minimalism would be a particularly dangerous strategy for liberal justices aiming in the future to correct the radical shrinking of constitutional rights that conservative justices have now achieved under a minimalist disguise. We need a renaissance of liberal principle in constitutional law. We need eloquent and bold opinions, in the tradition of the great justices of the past, opinions that can restate the fundamentals of a liberal constitutional jurisprudence.

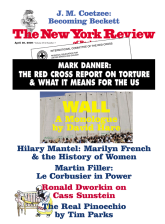

This Issue

April 30, 2009

-

1

For a full discussion of these hearings, see my book, The Supreme Court Phalanx: The Court’s New Right-Wing Bloc (New York Review Books, 2008).

↩ -

2

See Washington et al. v. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. 702 (1997); and my “[Assisted Suicide: What the Court Really Said](/articles/archives/1997/sep/25/assisted-suicide-what-the-court-really-said/),” The New York Review, September 25, 1997.

↩ -

3

See Sunstein, Legal Reasoning and Political Conflict (Oxford University Press, 1996).

↩ -

4

Roberts, Commencement Address at Georgetown University Law Center, May 21, 2006, cited by Sunstein, p. 43.

↩ -

5

See James Surowiecki, The Wisdom of Crowds (Abacus, 2004). An article Sunstein cites, Reid Hastie’s “Experimental Evidence on Group Accuracy,” in Information Pooling and Group Decision Making: Proceedings of the Second University of California, Irvine, Conference on Political Economy, edited by Bernard Grofman and Guillermo Owen (JAi, 1986), reports experimental tests of group accuracy. As the author notes, “Difficulties arise when the criterion for the judgment is not an objective or publicly verifiable event, condition, or ‘fact.’”

↩ -

6

See my article “[A Badly Flawed Election](/articles/archives/2001/jan/11/a-badly-flawed-election/),” The New York Review, January 11, 2001.

↩ -

7

For a defense of my criticism of the case, see “[The Curse of American Politics](/articles/archives/1996/oct/17/the-curse-of-american-politics/),” The New York Review, October 17, 1996.

↩ -

8

See my “[Why It Was a Great Victory](/articles/archives/2008/aug/14/why-it-was-a-great-victory/),” The New York Review, August 14, 2008.

↩ -

9

See The Supreme Court Phalanx.

↩ -

10

See “The Secular Papacy,” Judges in Contemporary Democracy, edited by Robert Badinter and Stephen Breyer (New York University Press, 2004).

↩