This is an online-only supplement to the April 30 issue of the Review.

Opening of the One World

Human Rights Film Festival,

Prague, Czech Republic,

March 11, 2009

I offer my congratulations to the recipients of this year’s Homo Homini Award and I am happy they came here from China. Allow me to make a few remarks. First, I think I will be speaking on behalf of most signatories of Charter 77 if I say that we are both pleased and honored to have inspired the Chinese Charter 08.

Secondly, I would like once more to point out our experience, one that our Chinese friends should adopt in one way or another, the experience that one may never reckon with success, one may never reckon with the situation changing tomorrow, the day after tomorrow, or in ten years. Perhaps it will not. If that is what you are reckoning with, you will not get very far.

However, in our experience, not reckoning with that did pay in the end; we found that it was possible to change the situation after all, and those who were mocked as being Don Quixotes, whose efforts were never going to come to anything, may in the end and to general astonishment get their way. I think that is important. In a peculiar way, there is both despair and hope in this. On the one hand we do not know how things will end, and on the other, we know they may in fact end well.

Thirdly, it is our experience—and this is perhaps more an appeal to our ranks—that international solidarity is very important and valuable. It helps, even if only as an encouragement to us, rather than as an argument convincing the powers that be. Having had firsthand experience with a totalitarian system and dictatorship ourselves, it is thus our duty to help those who are yet not able to enjoy freedom.

My final remark is altogether personal. I am deeply moved that the awardees present here were engaged in translating and circulating, in what manner was available to them, my texts.

Thank you.

Václav Havel

Writer and former President of the Czech Republic

Dear Representatives of People in Need, Dear President Václav Havel, Dear Foreign Minister, Ladies and Gentlemen, Friends,

We would like to thank the organization People in Need for giving the 2008 Homo Homini Award to the signatories of Charter 08. This award is an expression of support and encouragement for all those who are being persecuted for having signed the Charter, for all people in China who strive to exercise their legal rights, and for Dr. Liu Xiaobo, who was arrested and is still being detained for collecting signatures for the Charter. Doctor Liu Xiaobo has long pursued the ideals of human rights and democracy and has paid for this with a long-time confinement. It is for us an honor and a pleasant duty to accept the award in his stead.

Different people may see the significance of Charter 08 in different ways but all its signatories agree in one respect: the Charter speaks of fundamental values and aims of a civilized society. These values and aims are actually laid down in the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China and in a number of treaties and declarations which China has made as part of the United Nations. What we call for and what we demand is nothing but compliance with the existing obligations.

It is evident that Charter 08 is guided by the same spirit as Charter 77 was in its days. Yes, we did draw inspiration and encouragement from the Czechoslovak movement Charter 77, from the works of Václav Havel, from other Czech personalities. The two documents, Charter 77 and Charter 08, share certain similarities since the former Czechoslovakia and today’s China share a similar authoritarian ideology and style of governance, a similar social atmosphere and moral situation in an absence of truth and justice. Both Charters are also underpinned by the same principles based on adherence to international treaties and defence of human rights.

Just as Charter 77 once did, Charter 08 comes in a post-totalitarian time with an active civic perspective, ethos of citizenship and joint civic responsibility for public affairs. We are firmly convinced that the primary duty of a government is to maintain the freedom of the citizens, their dignity and their rights. If a government fails in this duty, if it persistently and systematically curtails citizens’ freedoms, dignity and rights, then it is necessary for each of us to stand up and say aloud what we think of such a government, for each of us to seek a remedy. We must not become resigned to living in fear and indifference, with being selfishly concern about our interests only.

Just like Charter 77, Charter 08 is not a subversive manifesto. We do voice criticism but our stance is on the whole constructive. We care about the development of a civic society in China: our ideal and objective is a healthy society, and as we reject the conservative political creed, we call for reforms of the political system and changes in the governing style. We spare no effort to engage in a dialogue with the government and we have to wait but also admonish. We don’t lack in courage or patience.

Advertisement

Charter 08 was published in order to achieve reconciliation and consensus; our goal is not confrontation. In their efforts to establish their rights, helpless Chinese people certainly do not consider their victory any of the defeats and difficulties that beset those exercising power. The signatories have a much stronger feeling of moral obligation and responsibility than the erstwhile revolutionaries wielding power in China today. It has always been the case in Chinese history that those desiring to seize power regarded every damage inflicted on society as a good means of weakening the powerful, and achieved their ends by stirring up unrest and provoking conflict and hatred. Although the Charter signatories are being persecuted in China, living under duress and coercion, we will not in any case abandon the rational and nonviolent campaign strategy.

The Chinese began to strive for a constitutional government more than a hundred years ago. These efforts still come across obstacles and have not yet been crowned with success. This is a result of the domestic political culture to which the element of freedom has always been alien, a consequence of civil wars and foreign aggressions, where the principal political fractions and powers relied on resolving problems not amicably, but with arms. The efforts to introduce a constitutional government in China are encountering a new and complicated situation.

Stalinism has not yet died of decrepitude and tries to prolong its life with the help of market economy, receiving infusions of fresh blood capital from the whole world. In the new combination of circumstances they have given birth to a monster.

Many people—in China and outside—regard the GDP growth rate in the country as an indicator of the government’s legitimacy. If there was political oppression in China thirty years ago, as in Czechoslovakia, the helpless in China now struggle not only for political rights, but also for social justice, and social and economic rights.

The core of Charter 08 is a demand for human rights, those that encompass all rights that make people human, encompass legal demands of people of varying social status, profession, nationality, gender, creed, and people of all fates. Although we run into many difficulties, we are full of confidence in the future of human rights and democratic constitutional government in China.

Human rights and democratic constitutional government in China are in principle affairs of the Chinese. At the same time, they are part of the global reality. Just as capital and technologies spread quickly and without restriction on the global scale, information and ideas cross rapidly borders and travel in all directions. The signatories of Charter 08, together with all inhabitants of China and the world, pay close attention to the current global economic crisis.

We who are facing a double crisis, economic and political, imprint deep on our hearts the interest and support we receive from Czech people. And with the same enthusiasm we watch your transformations and successes.

Xu Youyu

Dear Representatives of People in Need, Dear President Havel, Ladies and Gentlemen,

I stand here before you to speak about women. From the moment when the police took away Mr. Liu Xiaobo on December 8, 2008, his wife, Mrs. Liu Xia, could only see him once. Nor did she see him at the end of January, at the time of the spring festivities, the most important Chinese holidays. Mrs. Liu Xia tried to send books to her husband. First she was turned down but persisted and in the end she succeeded. I recently met Mrs. Liu. She is still waiting for an opportunity to see her husband again. She did not accept an invitation to come to Prague because she wants to be near her husband even if she cannot see him. She still waits for a car to come and take her to an unknown place where he is waiting to see her. She said she stayed by his side in constant expectation.

Behind every of these brave men, who have been deprived of freedom for their striving for human rights and democracy, stands a weeping yet strong woman. As you know, Mrs. Zeng Jinyan, wife of the imprisoned Mr. Hu Jia, looks after a little daughter and you can surely imagine her delicate situation. The struggle for human rights and democracy goes for these women hand in hand with their dearest and nearest, on whom they lavish all their love and care. These remarkable women are a firm foundation for our efforts and the source of our strength.

Advertisement

Behind the back of each of those men, who make sacrifices for the cause of human rights and democracy, stands also a weeping yet strong mother. There are the mothers of Tiananmen Square, whose children were killed by tanks twenty years ago. The pain of these mothers and their lamentation are to this day confined outside the space where the public can look, and their grief at the loss of beloved children is augmented by the authorities’ lack of cooperation. I know a mother whose son was shot dead in Tiananmen Square, aged twenty-eight. The stigma of “political culpability” is associated with this mother’s daughter, and the girl could not marry for long years because of her brother’s tragedy. Eventually she succeeded in starting a family but her husband, as well as their son, could not be told about the brother who was killed. How great a pain, and it cannot be expressed and must remain hidden in the heart. Some of the mothers, including the founder of the association, Professor Ding Zilin, stand in the first rank of those who call for human rights and democracy. Despite old age they carry in their own hands a torch of hope for the generations of our children.

I would also like to speak for the mothers of the victims of the Wenchuan earthquake. Their children died last year during an earthquake in the province of Sichuan, in ruins of schools whose construction did not comply with standards. Racked by pain over the loss of a child, they are still demanding the truth about the reasons why it was schools that collapsed during the natural disaster, and [they still] seek justice. Like the mothers of the Tiananmen victims, they are confined outside the space where the public can look. Only rarely is a news item about them published, and their freedom to meet people from the outside is curtailed. In China there are also mothers of the victims of contaminated milk, whose demand to get justice done by way of law has not yet been satisfied.

These women and mothers and their dead children fill me with pain and concern. We must not forget about them and we must help them. Our remembrance and help, awareness of their suffering and admiration of their courage and the purity of love in us ceaselessly appeal to conscience, humanity, and morality, and remind us of the love and responsibility that we owe the world.

Thank you for the occasion to share my thoughts with you.

Cui Weiping

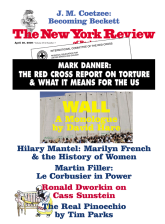

This Issue

April 30, 2009