As Fawcett and his small team—including his twenty-one-year-old son and his son’s closest friend—advanced into the jungles of Mato Grosso, they documented their adventures by sending dispatches to an increasingly enthralled public using Indian messengers. About four months into the journey, however, as they entered a region known to be populated by hostile Indian tribes, the missives abruptly ceased. Fawcett and his party vanished without a trace.

Their disappearance has been an unsolved mystery ever since. Had Fawcett and his companions been murdered by Indians? Had they renounced their ties to civilization and “gone native”? Evelyn Waugh was inspired by Fawcett’s story to write the blackly comic ending to his novel A Handful of Dust, in which the hero, Tony Last, ends up a captive in the Amazon, forced to read Dickens to a maniac for the rest of his life. Many later followed Fawcett’s footsteps—occasionally meeting an equally mysterious fate. These included Alfred de Winton, a fifty-two-year-old Hollywood bit-part actor who showed up in Cuiabá, Brazil, in 1934 and announced his determination to find Fawcett. Months later he sent a note out of the jungle saying that he was being held captive by Indians—then he, too, was never seen again.

Most recently, we have David Grann, a New Yorker writer who, while researching the suspicious death of a Sherlock Holmes expert in England in 2004, found a reference by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to Fawcett and his magical city. (Conan Doyle used the purported Indian civilization as the inspiration for The Lost World.) Grann became hooked by the mystery surrounding Fawcett’s tale, and by the unresolved debate over Z. “Like others, I suspect, my only impression of the Amazon was of scattered tribes living in the Stone Age,” Grann writes, “a view that derived not only from adventure tales and Hollywood movies but also from scholarly accounts.”

The result of Grann’s labors is The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon, the latest of the books about Victorian- and Edwardian-era adventurers battling the elements in forbidding corners of the earth. In The River of Doubt: Theodore Roosevelt’s Darkest Journey,1 Candice Millard described the retired, fifty-four-year-old president’s 1912 journey down an unmapped river in Brazil with his son, Kermit, and a legendary Brazilian cartographer, Cândido Mariano da Silva Rondon. (The latter also makes a brief appearance in Grann’s book.) Caroline Alexander’s The Endurance: Shackleton’s Legendary Antarctic Expedition2 recounted the great polar explorer’s ill-starred 1915 Antarctic mission, in which he and his crew spent twenty months stranded on the ice, then a smaller group had to row a twenty-foot boat 850 miles across the storm-tossed ocean to reach rescuers for those who had remained behind.

Grann’s book is part biography, part detective story, and part travelogue. Not only does he recount Fawcett’s journeys in pursuit of his lost civilization. He also describes how he himself—a New Yorker who suffers from a poor sense of direction, can’t see well in the dark, and would never climb a set of stairs when it was possible to take an elevator—embarked on his own quest for Fawcett, and the lost civilization that had fatally consumed him.

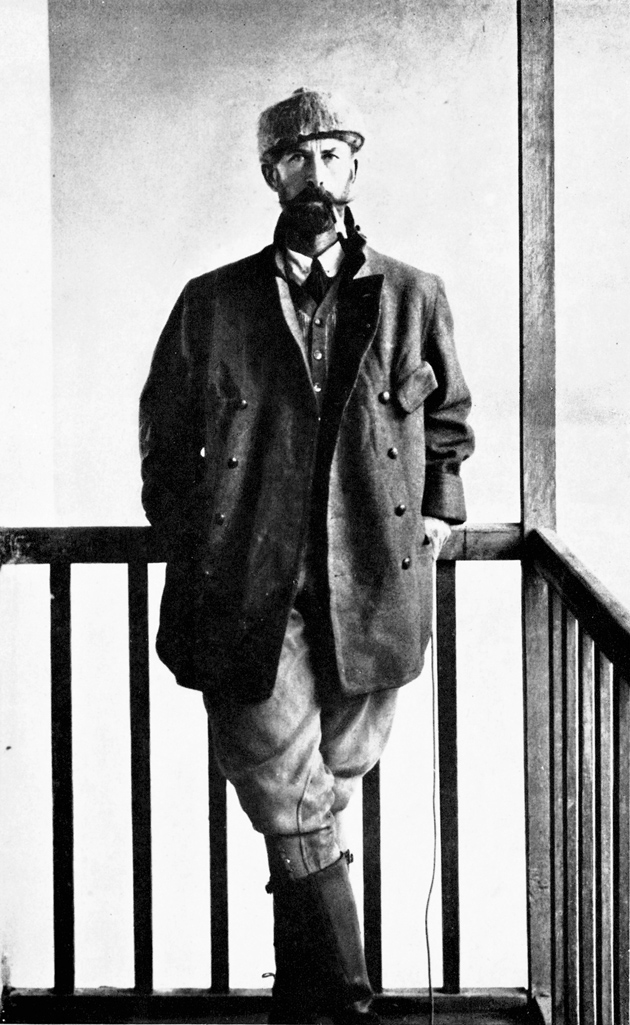

Percy Harrison Fawcett was born in 1867, the son of a Victorian aristocrat who had distinguished himself as a soldier and a cricketer but who degenerated into alcoholism and died of consumption at the age of forty-five. Fawcett’s widowed mother, a cold, domineering woman (he called her “hateful” in a letter to Conan Doyle, another driven son of an alcoholic), sent him against his will to the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich, England. Fawcett chafed at the discipline but absorbed the school’s message that the role of the Englishman was to colonize, Christianize, and otherwise uplift the “primitive” peoples of the world.

Advertisement

Upon his graduation, he was shipped off with the Royal Artillery to Fort Frederick in Trincomalee, a quiet port in Ceylon, in the far reaches of the empire. While he was stationed there, a colonial administrator handed him a scrawled note, given to him by a village headman, saying that a treasure of jewels and gold was stashed in a cave in the ruins of an ancient city called Galla-pita-Galla. Fawcett never found the treasure, or the city, but his travels to the remote interior of the country— a land of tea estates, jungled mountains, and the ruins of ancient civilizations, all beautifully evoked by Grann—awakened a yearning for adventure and a fascination for lost worlds that would define him for the rest of his life.

In 1900, Fawcett left the army and enrolled in a year-long “explorer’s course” at the Royal Geographical Society, the venerable institution that had sponsored such expeditions as Richard Burton and John Speke’s search for the source of the Nile. In the stuffy atmosphere of that London academy, Fawcett set himself apart. He impressed his teachers with his quick mastery of the tools of the explorer’s craft—including the theodolite, which could be used to determine the angle between the horizon and celestial bodies and thus one’s position anywhere on earth—and attracted mentors who saw in him a successor to Speke and Burton.

Six years later, after a stint as a spy for the British government in Morocco, he was dispatched by the RGS on his first assignment in the Amazon: a journey to map the disputed border between Bolivia and Brazil. Fawcett sailed to Panama aboard a rickety freighter filled, he later wrote, with “toughs, would be toughs, and leather faced old scoundrels.” From there, he caught another ship for Brazil, and then climbed by train over the snow-capped Andes and down into La Paz. Passing through rough-and-tumble settlements where Indians were kept as slaves by unscrupulous rubber barons, he entered the heart of the jungle. Grann describes a nightmarish landscape in which piranhas and electric eels infested rivers and streams, and stampeding, white-lipped wild pigs were in the jungle. The worst, he writes, were the insects:

The sauba ants that could reduce the men’s clothes and rucksacks to threads in a single night. The ticks that attached like leeches (another scourge) and the red hairy chiggers that consumed human tissue. The cyanide-squirting millipedes. The parasitic worms that caused blindness. The berne flies that drove their ovipositors through clothing and deposited larval eggs that hatched and burrowed under the skin. The almost invisible biting flies called piums that left the explorers’ bodies covered in lesions. Then there were the “kissing bugs,” which bite their victim on the lips, transferring a protozoan called Trypanosama cruzi; twenty years later, the person, thinking he had escaped the jungle unharmed, would begin to die of heart or brain swelling.

Fawcett moved through hostile landscapes that killed some men and drove others insane. Where others starved, Fawcett turned himself into an expert hunter and survivalist. Where others fell victim to pit vipers and other predators, Fawcett had an uncanny ability to sense—and elude—an impending attack. Where others suffered debilitating bouts of malaria or suppurating infections that then became infected by maggots, Fawcett almost never became sick or injured. One historian observed that Fawcett had “a virtual immunity from tropical disease.”

As Grann demonstrates with a kind of horrified fascination, Fawcett’s sense of his own invulnerability often made him impervious to the sufferings of the men he brought with him into the jungle. One of the most memorable sections of Grann’s book recounts the story of Fawcett’s fourth Amazon expedition in October 1911, a Royal Geographical Society–sponsored mission to map the Heath River between Bolivia and Peru and document the flora and fauna of the region. Fawcett chose as his second-in-command a figure of equal repute: the Glasgow-born naturalist James Murray, who had gained fame as the lead scientist on Ernest Shackleton’s 1907 expedition to Antarctica. The pairing of Fawcett and Murray—the great Amazon explorer and the great polar scientist—seemed like “the perfect match,” writes Grann. “The Royal Geographical Society had encouraged the excursion, and why not?”

What neither the explorers nor the society seemed to have taken into account, however, was that though each man had excelled in his own challenging environment, Murray was utterly out of his depth in the jungle:

A polar explorer has to endure temperatures of nearly a hundred degrees below zero, and the same terrors over and over: frostbite, crevices in the ice, and scurvy. He looks out and sees snow and ice, snow and ice—an unrelenting bleakness…. In contrast, an Amazon explorer, immersed in a cauldron of heat, has his senses constantly assaulted. In place of ice there is rain, and everywhere an explorer steps some new danger lurks: a malarial mosquito, a spear, a snake, a spider, a piranha. The mind has to deal with the terror of constant siege.

In temperament as well as physical conditioning, Murray was the worst of all possible companions for the demanding Fawcett. At forty-six, he was already past his prime, a shrunken, stooped, and wizened figure who suffered from “inflamed eyes” and a bad case of rheumatism. Moreover, his vaunted feats of exploration had been wildly overpraised: Murray had remained at the base camp while Shackleton and the rest of the team had embarked on the most brutal segment of the journey.

Advertisement

The Amazon expedition turned into a debacle. Murray fell further and further behind. He struggled beneath a sixty-pound pack, his feet ached, he got lost, he grew demoralized and delirious, vampire bats sucked his blood while he slept, and he fell into a river and nearly drowned. “One of his fingers grew inflamed after brushing against a poisonous plant,” Grann writes.

Then the nail slid off, as if someone had removed it with pliers. Then his right hand developed, as he put it, “a very sick, deep suppurating wound,” which made it “agony” even to pitch his hammock. Then he was stricken with diarrhea. Then he woke up to find what looked like worms in his knee and arm. He peered closer. They were maggots growing inside him. He counted fifty around his elbow alone. “Very painful now and again when they move,” Murray wrote.

The Royal Geographical Society, which was embarrassed by the scandal, pressured Fawcett to issue Murray an apology, though there is no evidence that he ever gave one. “The very things that made Fawcett a great explorer—demonic fury, single-mindedness, and an almost divine sense of immortality—also made him terrifying to be with,” Grann writes. “Nothing was allowed to stand in the way of his object—or destiny.” (One year later, Murray, apparently out to redeem himself, embarked on a Canadian expedition to the Arctic; the team’s boat became caught in the ice, and they were forced to escape on dogsleds across the snowy wastes; they were never seen again.)

The recounting of Fawcett’s half-dozen treks into the Amazon could have become monotonous in the hands of a less gifted writer. And sometimes, indeed, a sense of claustrophobia does set in: How many descriptions of poisonous snakes, wounds filled with maggots, and bodies wracked with fevers do we really need? But Grann uses each journey to shed further light on Fawcett’s personality, and, for the most part, he manages to avoid the tedious repetition that might have sunk his narrative. Grann also breaks up Fawcett’s story with brief yet tantalizing chapters about his own preparations to follow the explorer’s trail into the Amazon. This was a shrewd narrative decision: Grann’s journey becomes a monomaniacal quest in its own right, taking him from the archives of the Royal Geographical Society in London to the home of Fawcett’s granddaughter, and finally to Brazil.

The transformation of this self-described couch potato into a twenty-first-century Amazon adventurer can be both humorous and oddly melancholy—it provides a reminder of how much of the excitement of Victorian-era travel has been lost in the modern age. Visiting a giant store in Manhattan, for example, Grann gazes in awe at “rainbow-colored tents and banana-hued kayaks and mauve mountain bikes and neon snowboards dangling from the ceilings and walls.” Such forays make him, and us, appreciate even more the conditions in which Burton, Shackleton, and Fawcett worked.

But ultimately, what makes The Lost City of Z so enthralling is the complexity of its main character. Intolerant of weakness, capable of acts of heartlessness to the men under his command, Fawcett could also be surprisingly kind and gentle. In contrast to many Amazon researchers, Fawcett had a benevolent attitude toward Indians and went to great lengths not to harm them. He lashed out at the slave traders he encountered in 1906 as “savages” and “scum,” wrote editorials against them in British newspapers, and, in the journal of the Royal Geographical Society, denounced

the wretched policy which created a slave trade, and openly encouraged a reckless slaughter of the indigenous Indians, many of them races of great intelligence.

Grann describes one scene on the Heath River in Bolivia in 1910 in which Fawcett and his team, traveling in canoes, came under a shower of arrows from Guarayo Indians gathered on the riverbank. Instead of scrambling for cover, Fawcett waded across the stream against the fusillade, waving a handkerchief in greeting while shouting out the local word for “friend.” The Indians stopped shooting and took Fawcett into the forest with them. Nearly one hour later, Grann writes, Fawcett “emerged from the jungle with an Indian cheerfully waving his Stetson.”

By contrast, in 1920, Fawcett’s main rival in Amazon exploration, a Boston Brahmin physician named Alexander Hamilton Rice, was approached by Yanomani Indians while on a journey along the Casiquiare, a two-hundred-mile natural canal that linked the Orinoco and Amazon rivers. The Indians pointed their drawn bows at the rifle-bearing white men, and Rice, alarmed, ordered his men to fire warning shots over their heads—then to shoot to kill. Rice defended the consequent massacre as an act of self-defense, but Fawcett told the Royal Geographical Society that shooting Indians was reprehensible and scorned his rival for his “skedaddle” from the scene.

Between 1906 and the outbreak of World War I, Fawcett made six treks into the Amazon; he mapped thousands of square miles and gathered reams of detail about indigenous wildlife and Indian tribes. It appears that the quest for Z took hold of him gradually during these expeditions, beginning with his discovery of cave paintings and shards of pottery that dated to the pre- Columbian era, and intensifying after he came across Indians who had developed extensive agriculture in the rain forest: this evidence made it clear that Amazon Indians were not all, as most scientists and anthropologists believed, primitive hunter-gatherers, but could cultivate the soil and establish permanent settlements in cleared sections of tropical wilderness.

Fawcett’s imagination was fired by stories of El Dorado, the mythical city of gold that had drawn the Spanish conquistadores. While he agreed that the conquistadores’ vision was an “exaggerated romance,” he believed that the jungle harbored the remains of complex and densely populated civilizations. In the sixteenth century the Spanish priest-adventurer Gaspar de Carvajal had even claimed to have seen these urban dreamscapes, describing wide highways slashing through the rain forest, leading to villages overflowing with fruits and vegetables and filled with “temples, public squares, palisade walls, and exquisite artifacts.”

While most Victorian geographers and explorers dismissed such descriptions as “full of lies,” Fawcett was certain that vestiges remained. He turned to unorthodox methods to confirm their existence. “He increasingly surrounded himself with spiritualists who not only confirmed but embroidered on his own vision of Z,” Grann writes. “One seer told him: ‘The valley and city are full of jewels, spiritual jewels, but also immense wealth of real jewels.'” As his obsession deepened,

Fawcett published essays in journals, such as the Occult Review, in which he spoke of his spiritual quest and “the treasures of the invisible World.”

Another South American explorer and RGS fellow said that many people thought that Fawcett had become “a trifle unbalanced.” Some called him “a scientific maniac.”

In the spiritualist magazine Light, Fawcett contributed an essay titled “Obsession.” Without mentioning his own idée fixe, he described how “mental storms” could consume a person with “fearful torture.” “Undoubtedly obsession is the diagnosis of many cases of madness,” he concluded.

Grann’s reconstruction of Fawcett’s doomed 1925 journey is the most moving part of the book. By then Fawcett had determined that “Z” probably lay in what is now the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso, north of the river outpost of Cuaibá. Desperate for funds, short on credibility, and racing against time—his rival, Alexander Hamilton Rice, was assembling his own expedition, complete with radio sets and a float plane—the aging explorer cast about the world for money and companions. T.E. Lawrence, the celebrated desert adventurer, volunteered to go with him, but Fawcett turned him down; he had learned from the Murray experience a decade earlier to avoid men with big egos and no jungle experience. Finally he turned to the one person who regarded him with unquestioning trust: his twenty-one-year-old son, Jack, who idolized his father and dreamed of a career in Hollywood. Jack then recruited Raleigh Rimell, his inseparable companion since their boyhood in Devonshire. Fawcett’s wife, Nina, who remained loyal throughout his increasingly penurious life, “raised no objections,” Grann writes.

Partly, she was confident that Fawcett’s seemingly superhuman powers would protect their son, and, partly, she believed that Jack, as his father’s natural heir, would possess similar abilities. Yet her motivation seems to have gone deeper than that: to doubt her husband after so many years of sacrifice was to doubt her own life’s work. Indeed, she needed Z just as much as he did.

Nina’s desperate belief in her husband, the boyish enthusiasm of Jack Fawcett and Rimell, the latter’s rising fear as his fantasy of fame collided with the horrors of the jungle—all elevate the story from a tale of madness into tragedy. The images of the three men hacking through the forest toward the territory of the Xavante Indians—“they generally kill anyone they can easily catch,” a nineteenth-century German traveler wrote—have an almost unbearable poignancy. Toward the end, Fawcett, sensing Rimell’s distress, tries to get him to return to civilization with some fever-stricken guides, but Rimell refuses to give up. “I shall look forward to seeing you again in old Cal when I return,” Rimell writes to his mother in one of his final missives. He advises his brother: “Keep cheerful and things will turn up alright as they have for me.”

Eighty years later, his pack filled with freeze-dried food and state-of-the-art gadgetry, Grann arrives in the Amazon and sets forth in the footsteps of his quarry. Trekking down rain-forest footpaths and traveling by riverboat into remote settlements where Indian tribes dwell in longhouses and still have little contact with the modern world, Grann begins to sense the awe, the terror, and the isolation that the band of explorers must have experienced. I won’t give away the discoveries that Grann makes above Dead Horse Camp B, where Fawcett and his team sent out their final message. It’s a little bit of a letdown—how can it not be?—though the mystery surrounding Fawcett’s disappearance remains largely intact.

In the end, what is most striking about The Lost City of Z is the portrait that Grann gives of a vanished world. Adventurers of a century ago who probed polar ice caps and the Amazon rain forest did so without the aid of GPS systems and snakebite kits, without global satellite communications, lip balms, or portable hot-water showers. Thrust into the most hostile environments imaginable, utterly cut off from the outside world, they were forced to survive on their wits and their courage. The alternative was death. It is a world that Grann brings back wondrously to life.

This Issue

May 14, 2009