1.

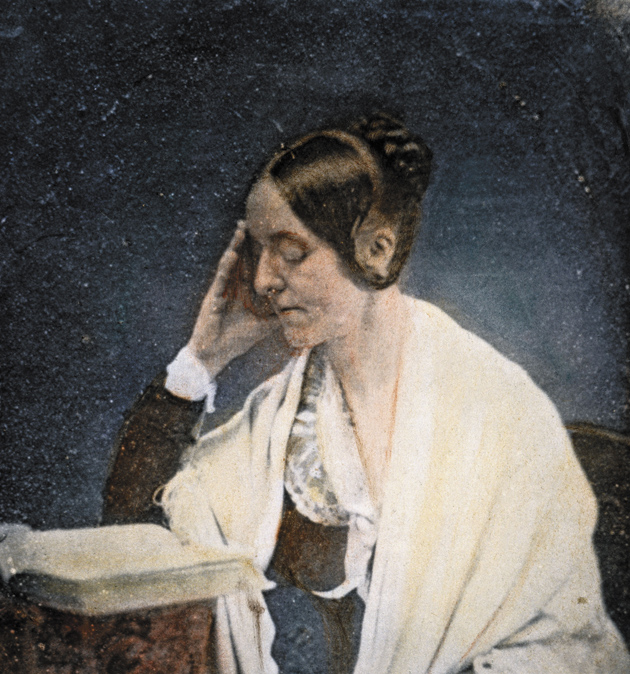

With impediments in her way—she did not attend college, she wasn’t rich or conventionally beautiful, she was prone to physical and psychological ailments—Fuller continually sought a wider scope for her ambitious undertakings, as if, as her intimate friend Emerson remarked, “this athletic soul craved a larger atmosphere than it found.” Fuller’s extensive network of friends included Hawthorne and Thoreau, Horace Greeley and Edgar Allan Poe, along with assorted Harvard professors, Unitarian ministers, social reformers, and their far-flung sons and daughters. “I now know all the people worth knowing in America,” she once announced, “and I find no intellect comparable to my own.”

Fuller’s field widened again during the 1840s when she achieved her long-cherished dream of traveling abroad, and met Thomas Carlyle, George Sand, the Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz, and the Italian leader-in-exile Giuseppe Mazzini. She became personally involved in the doomed Italian movement for independence of 1848–1849, secretly marrying a participant in that struggle and having a child with him. She remained in Rome as French, Austrian, and Neapolitan armies converged to “liberate” the city, and she worked heroically in a Roman hospital caring for the wounded.

During her sometimes improbable and ultimately tragic life—a life that George Eliot might have imagined—Margaret Fuller became, as her biographer Charles Capper points out, the first of many things:

America’s first female highbrow journal editor, first intellectual surveyor of the new West, author of the first philosophical American book on the woman question, first literary editor of a major metropolitan newspaper, first important foreign correspondent, and first famous American European revolutionist since Thomas Paine.

She died at the age of forty, under heartbreakingly dramatic circumstances, in a shipwreck off Fire Island in July 1850, as she was returning with her fledgling family to the United States.

And yet Fuller’s personal temperament and her literary legacy remain elusive. Those who knew her best left conflicting testimony about her. They cannot agree on what she looked like, or whether her late marriage (if indeed she really was married) was a triumph or a joke, or whether she was a major writer, and if so what kind. According to her contemporaries, her books never captured her coruscating voice anyway—“the crackling of thorns under a pot,” as Emerson described it.2

Under the circumstances, what is most needed is a fresh marshaling of the evidence, some of which has only recently come to light, in order to pose the question anew: Who was Margaret Fuller and what exactly did she achieve? This is the challenge undertaken by Charles Capper, an intellectual historian based in Boston, in the two volumes of his superb biography, the first of which was published in 1992.3

2.

In the affecting Autobiographical Romance that Fuller wrote when she was thirty, she adopted the tone of Goethe’s self-pitying Werther or Chateaubriand’s René. “I look back on these glooms and terrors,” she wrote in a typical passage, “and perceive that I had no natural childhood!” It testifies to Capper’s careful work that his well-paced narrative and sympathetic sense of Fuller’s intellectual and emotional growth, what she called her “unfolding,” do not seem to deflate her life in any way.

Margaret Fuller was born in 1810, the eldest of nine children, in a charmless neighborhood on the outskirts of Cambridge, which hopeful developers called “American Venice” because of the nearby Charles River. The Fuller family lived in an ugly house with a view of a soap factory across the street. Fuller’s father, Timothy, was a lawyer elected four times to Congress before he fell out with Andrew Jackson in 1825 and retired to Cambridge to practice law and to write. Fuller’s earliest memory was the death of a younger sister in 1813: “Thus my first experience of life was one of death.” She was never close to her grieving mother as a child.

Timothy Fuller recognized the intellectual promise of his daughter and taught her languages, literature, history, music, and philosophy. One is reminded of Emily Dickinson’s words about her own father, like Fuller a congressman and lawyer proud of his precocious daughter: “Father, too busy with his briefs—to notice what we do—He buys me many Books—but begs me not to read them—because he fears they joggle the Mind.” Timothy Fuller insisted that Margaret read the books, often keeping her up quite late, when his legal work was done, in order to examine her on what she had learned. She began to read Latin when she was six. “By ten,” Capper reports, “she had read through most of the standard Virgil, Caesar, and Cicero, and, within another couple of years, a good deal of Horace, Livy, Tacitus….” She drew from this reading a lifelong admiration for Roman will and resolve:

Advertisement

Who, that has lived with those men, but admires the plain force of fact, of thought passed into action? They take up things with their naked hands. There is just the man, and the block he casts before you,—no divinity, no demon, no unfulfilled aim, but just the man and Rome, and what he did for Rome. Everything turns your attention to what a man can become, not by yielding himself freely to impressions, not by letting nature play freely through him, but by a single thought, an earnest purpose, an indomitable will, by hardihood, self-command, and force of expression.

Some observers have seen something sinister in Timothy Fuller’s strenuous regime, and have found support in Margaret’s own account of childhood hallucinations, nightmares, somnambulism, and “attacks of delirium.” Perry Miller, the distinguished historian of American Puritanism, wrote that Timothy Fuller “dominated the family with a tyrannical masculinity that he thought was affection, but that actually amounted to what must be called persecution, or even sadism.”

Meg McGavran Murray goes farther in her new psychoanalytic biography, calling Fuller “a sentimental yet sadistic man with a hot temper and a compulsive need to charm and control women.” Murray is particularly disturbed by “Timothy’s routine at night of entering the room where his children slept ‘and pressing a kiss upon their unconscious lips.'” Margaret’s childhood dreams of horses trampling her body and trees dripping blood are, according to Murray, “like those experienced by people who have survived severe trauma.” They are also like those experienced by people who have read Virgil.

Actually, the only unusual aspect of Margaret’s educational regimen was that she was a girl. As Capper points out, precocious boys bound for Harvard were on a similar and sometimes faster track. James Russell Lowell “was an avid reader of French literature at the age of seven,” Thomas Wentworth Higginson “read Latin by eight and entered Harvard at thirteen,” while Josiah Quincy, son of the Harvard president, “was reading Virgil by six.” Capper rejects the melodramatic interpretation that Perry Miller and others, including Fuller herself, have given to her home schooling. He finds in Timothy Fuller’s letters, “largely ignored by her biographers,” ample evidence that he was “consistently liberal-minded in his intellectual treatment of Margaret.”

3.

After Timothy Fuller’s sudden death from cholera in 1835, Margaret Fuller was forced at age twenty-five to support her large family. She taught at Bronson Alcott’s progressive school in Boston and then at a school in Providence. Her father’s death and the demands of teaching forced her to give up two long-cherished projects. One was a trip to Europe; the other was a life of Goethe. Inspired by Carlyle’s admiration of Goethe, she had taught herself German—as Emerson noted, she seemed “to have learned all languages, Heaven knows when or how.”

Fuller first met Emerson during the summer of 1836, after what he called “a little diplomatizing in billets by the ladies,” especially the English writer and abolitionist Harriet Martineau, who had been impressed by her “excelling genius and conversation.” Emerson was initially put off by Fuller’s “extreme plainness,” the “nasal tone of her voice,” and a nervous tic of “incessantly opening and shutting her eyelids.” He was braced for bad manners, having heard accounts of Fuller’s scornful arrogance. “The men thought she carried too many guns,” he wrote, “and the women did not like one who despised them.”

Emerson was struggling with the unfinished manuscript of his first book, Nature, and still finding his voice as a writer. He found that Fuller’s presence elicited the best in him, as he wrote in the handsome tribute included in Fuller in Her Own Time:

She disarmed the suspicion of recluse scholars by the absence of bookishness. The ease with which she entered into conversation made them forget all they had heard of her; and she was infinitely less interested in literature than in life. They saw she valued earnest persons, and Dante, Petrarch, and Goethe, because they thought as she did, and gratified her with high portraits, which she was everywhere seeking. She drew her companions to surprising confessions. She was the wedding-guest, to whom the long-pent story must be told….

She was also the houseguest who stayed too long; her flirtatious monopolizing of Emerson’s attentions left his wife in tears.4

Advertisement

Fuller put her skills to use in her “Conversations,” her distinctive contribution to the education of American women. Beginning during the winter of 1839, and continuing for five years, twenty-five women paid a high price to spend two hours with Fuller and talk on such subjects as Greek mythology, the arts, and education. She had published a translation of Eckermann’s Conversations with Goethe earlier that year, and “tuned up” for her conversations by reading Plato’s dialogues. The aim, she wrote, was to pose “the great questions. What were we born to do? How shall we do it?” Her pupils included the Peabody sisters Sophia and Mary, who married Hawthorne and the educational reformer Horace Mann, respectively; Emerson’s stately and mystically inclined wife, Lidian; and the tough-minded abolitionist writer Lydia Maria Child.

At Emerson’s invitation, Fuller began editing the Dial, whose first issue was published during the summer of 1840. The aim of the journal was to spread the views of the writers and thinkers who called themselves Transcendentalists, for their conviction that “transcendent” ideas could change people’s lives and the society in which they lived. It was in the Dial, in 1843, that Fuller, the lawyer’s daughter, published her controversial essay on women’s rights, titled “The Great Lawsuit,” later incorporated into her book Woman in the Nineteenth Century, her best-known work today.

The “Lawsuit,” which might be considered the theoretical underpinning of her more practical Conversations, advances strong arguments for women’s education, suffrage, and equal pay for equal work, along with a sharp analysis of the phenomenon of the “old maid,” but it is written in an uneven and sometimes grating style that lurches from the legalistic to the lyrical. “What woman needs is not as a woman to act or rule,” she wrote, “but as a nature to grow, as an intellect to discern, as a soul to live freely, and unimpeded to unfold such powers as were given her when we left our common home.” A journey west, to Niagara Falls and the Great Lakes, elicited something less crabbed and more richly observed. The resulting book, Summer on the Lakes, in 1843, makes its own reformist arguments, about Indian rights and the vanishing wilderness, in a more engaging way. “Wherever the hog comes,” she lamented, “the rattlesnake disappears.”

Fuller’s ability to combine high-toned writing with a commitment to social reform attracted the attention of Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, who was trying to feature both in his popular newspaper. He offered her a generous salary; since she had never been paid for her work for the Dial, she quickly accepted. For the next two years, she wrote with precision and flair on a range of subjects—books, classical music, art exhibitions, prisons, prostitutes, immigrants, the poor—that no American journalist before Edmund Wilson could match. Twenty months in New York, she wrote, “presented me with a richer and more varied exercise for thought and life, than twenty years could in any other part of these United States.” A romance with a Jewish banker named James Nathan, who “sang and played lieder for Fuller on his guitar,” was part of that varied exercise. When Nathan made a pass at her, she was appalled; then she discovered that he was living with a prostitute he had supposedly “rescued.” He asked Fuller to take care of his dog while he traveled, accompanied by his fallen woman, to Europe.

Fuller’s book reviews have never received the attention they deserve. Amid the chaos and contention of American publishing, when “Young America” nativists vied with self-styled cosmopolitans for readers’ attention, Fuller was able to identify the most vigorous and promising writers of her time: Emerson, Hawthorne, Poe, Frederick Douglass, and Melville. Her achievement goes beyond the simple naming of writers we now consider classic. She was reading their books at an early stage in their careers, and did not live long enough to read Hawthorne’s novels or to find the promise of Typee—in which she relished the savage irony directed at missionaries in Hawaii and the South Seas—fulfilled in Moby-Dick and “Bartleby the Scrivener.”

She could see that her friend Poe, dismissed by Emerson as the “jingle man,” was doing something fresher and more daring than Longfellow’s graceful adaptations of European models. In her notorious essay on Longfellow, much resented by her Boston friends, Fuller dismissed Poe’s claims that Longfellow was a plagiarist, noting that “we had supposed it so obvious that the greater part of his mental stores were derived from the works of others.” She quoted a few lines from one of his poems:

Beneath some patriarchal tree

I lay upon the ground;

His hoary arms uplifted be,

And all the broad leaves over me

Clapped their little hands in

glee….

“What an unpleasant mixture of images!” she wrote. “This idea of the leaves clapping their little hands with glee is taken out of some book…and jars entirely with what is said of the tree uplifting its hoary arms.” Longfellow, she concluded, was overrated in America “because through his works breathes the air of other lands with whose products the public at large is but little acquainted.” She predicted, correctly, that in the future “he will rank as a writer of elegant, if not always accurate taste, of great imitative power, and occasional felicity in an original way, where his feelings are really stirred.”

4.

While Longfellow’s cosmopolitanism struck Fuller as secondhand and second-rate, she herself had long wished to travel to Europe and meet the writers she most admired. She got her chance in 1846 when wealthy friends asked her to accompany them and tutor their child. In London, the crusty Carlyle found her “a strange lilting lean old-maid,” but “not nearly such a bore as I expected.” “A sharp subtle intellect too,” he reported to Emerson, “and less of that shoreless Asiatic dreaminess that I have sometime met with in her writings.” Through Carlyle she met the Italian patriot Mazzini, whose poetic temperament and fierce political engagement she found deeply appealing. She called him “by far the most beauteous person I have seen.” She agreed, with that flare for physical courage she later showed in Rome, to help smuggle him into Italy, a dangerous plan later abandoned.

In France, Fuller received a sentimental education that challenged the rigid morality of her American friends. She gave up searching for Balzac after learning that he frequented “the lowest cafés,…so that it was difficult to track him out,” but she warily approached George Sand, knowing she lived out of wedlock with Chopin, and proclaimed, “I never liked a woman better.” With the Polish poet Mickiewicz, a passionate advocate of Emerson’s works abroad, she formed a romantic friendship that continued in letters as she traveled on to Italy. Mickiewicz suggested that it might be time for her to consider “whether you are permitted to remain a virgin.”

It is tempting to portray Fuller’s Roman spring as an “awakening” of her erotic self. “It was springtime in Rome,” as Murray puts it in her typically hothouse phrasing, “where a pagan earthiness exudes from every rock and ruin, and Fuller, in tune, felt her body pulsate and open to the sun, like the orange blossoms whose fragrance lay heavy in the air.” A page later, amid the colonnades of St. Peter’s, the “dark-haired, well-bred Giovanni Angelo Ossoli” slides into view, “in the context of pagan Rome where the warm spring wind carried with it the musky odor of urine-stained ruins mixed with the sweet scent of orange blossoms and jasmine.”

What is one to make of Fuller’s relationship with Ossoli? He was more than ten years younger than she was, his education was rudimentary, and he spoke no English. No one suggests that he was her intellectual equal, though Hawthorne’s later claim that he was “clownish” and “half an idiot” seems extreme.5 Capper’s assessment is characteristically sane and plausible:

Although it was, indeed, an ironic, if not bizarre, match for America’s most self-consciously intellectual woman—and certainly not the egalitarian or “sacred” one she had often panegyrized—it nonetheless had, as she often said, an aura of intimate reality that was refreshing and new.

In the absence of a marriage certificate, there has been much speculation concerning the precise status of Fuller’s relations with Ossoli. Capper weighs the evidence carefully and concludes, “It now seems almost certain that at some point Fuller did secretly marry,” and he leans toward a probable date of April 4, 1848, when she was already pregnant. “I acted upon a strong impulse,” she wrote to her sister. “I neither rejoice nor grieve, for bad or for good I acted out my character.” As a revolutionary nobleman from a family that was part of the papal court, Ossoli had a certain romantic appeal for her, and linking her fate with his meant that Fuller was personally engaged with the political cause of Italian independence. She experienced the departure of Pius IX from the city in November 1848, and the declaration of the Roman Republic and the triumphal return of Mazzini in February 1849. Meanwhile, she had placed her child, Nino, with a wet nurse in the safer countryside.

“I write you from barricaded Rome,” Fuller began her dispatch to the Tribune on May 6, 1849. “The Mother of Nations is now at bay against them all.” Holed up in a house on the Via Gregoriana near the Spanish Steps, Fuller, the last American in the city, witnessed the intense street-fighting as the siege of Rome by French troops began. She lobbied for American support for her doomed cause. “I listen to the same arguments against the emancipation of Italy, that are used against the emancipation of blacks.” She labored in the hospital on an island in the Tiber. Meanwhile, she was writing, she told friends, her major work, a history of the Roman uprising. When the Roman Republic was defeated and thousands of partisans were slaughtered in the streets, the little family fled to Florence, making preparations for the trip to America, where financial prospects seemed more promising.

Fuller, surprisingly superstitious for such a sturdy intellect, and with a taste, as Emerson said, for “gems, ciphers, talismans, omens, coincidences, and birth-days,” had premonitions of doom for the voyage. Things went wrong from the start. The captain died of smallpox; Nino, too, almost died of the disease. At the end of the two-month crossing, on a slow merchant ship instead of a steamboat, which they couldn’t afford, the first mate miscalculated the entry to New York Harbor and ran aground on a sandbar a hundred yards off the coast of Fire Island. A storm further damaged the ship, and some of the crew swam safely to shore. One crew member tried to transport Nino, but both were drowned, as Fuller, wearing a white nightgown and holding on to the mast, watched in horror. Her body and that of her husband were never recovered, nor was the chest that supposedly held the manuscript of her history of the Roman Revolution. Thoreau, dispatched by Emerson to search for any remains, discovered a single button from Ossoli’s coat.

It reads like martyrdom, but to what exactly? Not to revolution, like Lord Byron or Rosa Luxemburg, and not really to art and literature, like Keats, who died just below Fuller’s house on the Spanish Steps. To love, perhaps? To the grinding conditions of poverty, which she eluded for a time, only to fail at the end, like one more desperate immigrant in sight of land, in a bad boat with an incompetent captain, and scavengers watching from the beach for valuable cargo? “Almost every chest & box,” Thoreau reported with disgust, “was broken open with thievish & dare devil curiosity by night & by day.”

As one looks back over her life, it is the incessant work that stands out, the sheer labor, from the Latin drills at midnight under her father’s vigilant regime to the hundreds of articles and translations edited for the Dial and written for the Tribune. For a time, it seemed as though she was carrying the hopes of American literature on her fragile shoulders. And then, in her final chapter, she assumed the impossible triple demands of caring for a newborn child, writing about the war in the streets in which her husband was engaged, and running a hospital. How could she do it all? She couldn’t. But what if her ship had quietly docked in Brooklyn?

This Issue

May 14, 2009

-

1

See “A Heroine of Revolution,” a review of J.P. Nettl, Rosa Luxemburg (Oxford University Press, 1966), The New York Review, October 6, 1966. A revised version of the article, from which this passage is quoted, is included in Arendt’s Men in Dark Times (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1968).

↩ -

2

The phrase, from Ecclesiastes, recurs in Robert Lowell’s “To Margaret Fuller Drowned”: “Your voice was like thorns crackling under a pot.” See Lowell’s Notebook (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1970), p. 90.

↩ -

3

Margaret Fuller: An American Romantic Life: The Private Years (Oxford University Press).

↩ -

4

Fuller figures prominently in Susan Cheever’s racy American Bloomsbury (Simon and Schuster, 2006), in which Cheever, like others before her, suspects that there was more than intellectual exchange in Fuller’s friendship with Emerson. She is particularly intrigued by moonlit walks in and around Concord, and believes that Emerson was suspicious (as is she) that there was also something afoot between Fuller and Hawthorne. Cheever’s lively and well-written book, which fans fires where few have found smoke, is perhaps best treated as a historical novel.

↩ -

5

In his journal, Hawthorne wrote of Ossoli’s failed apprenticeship with a sculptor: “after four months’ labor, Ossoli produced a thing intended to be a copy of a human foot; but the ‘big toe’ was on the wrong side.”

↩