With a fitting touch of drama, even melodrama, Michael Holroyd opens his composite biography with the death by suicide, at the age of twenty-one, of one of its two most important characters. One night in 1868, after the London theaters had closed, the actress Ellen Terry’s family found in her bedroom a portrait of her estranged husband, the artist G.F. Watts—known (to some) as “England’s Michelangelo”—to which she had pinned a note reading “Found Drowned,” the title of one of Watts’s paintings. Her parents instituted a search and reported Ellen’s disappearance to the police. A few days later her father identified the body of a girl who had drowned in the river Thames as that of his daughter.

He was wrong, of course. In fact Ellen had gone to live with the widower Edward Charles Godwin, an architect-artist, with whom she was to have two illegitimate children. She was also to become the greatest English actress of her age as well as the partner on stage and in real life of its greatest actor-manager, Henry Irving. Together they were not only to dominate the English stage during the later part of the nineteenth century and beyond, but also to make a number of lengthy and triumphal tours of the United States.

After Irving died Ellen was to return to America, for which she had great affection, both as an actress and to tour with her popular series of lecture recitals on Shakespeare. While there in 1911, at the age of sixty-three, she recorded ten extracts from Shakespeare plays. Some were destroyed, but others, including Portia’s “mercy” speech, Ophelia’s mad scenes, and the potion scene from Romeo and Juliet, can still be heard on CD.1 The voice is wide-ranging, with plangent chest tones and a silvery high register. Vowels are pure and elongated and there is a vivid sense of actorly presence. Though Portia’s speech is delivered somewhat ponderously, the others are not just recitations but genuine and impressive performances that help us to understand why she was so greatly admired.

Ellen’s two children were to achieve differing degrees of distinction: her daughter, Edith (or Edy), in a relatively low-key way as an indefatigable and multitalented social activist woman of the theater; and her son, Edward Gordon Craig, as a wayward, eccentric, but visionary designer, artist, and theorist who saw himself as the savior of the theater. He was to spend most of his long life working in various countries of Europe, forming liaisons and begetting children in many of them. Irving’s two sons, Henry and Laurence, though somewhat overshadowed by their father’s fame, also had successful careers as actors and men of the theater.

These six people’s joint lives, spanning well over a century, were intertwined with those of many of the most important and interesting figures of their time, including the playwrights George Bernard Shaw and Oscar Wilde, the dancer Isadora Duncan, the actor Herbert Beerbohm Tree and his half-brother Max Beerbohm, the actresses Eleanora Duse and Sarah Bernhardt, the great Russian director Konstantin Stanislavski, and the novelist Virginia Woolf. Their personalities, the interactions among them, and their relations with their society form the subject of Michael Holroyd’s enthralling new study.

One of the themes to emerge from this book is the rise in social status of the theatrical profession during the later nineteenth century. It is all the more remarkable that this should have come about largely as a result of the careers of Terry and Irving since both of them led irregular private lives. Ellen Terry came from a relatively humble theatrical family, but her exceptional gifts as an actress were apparent even in her childhood. She made her London debut with Charles Kean at the Princess’s Theatre in 1856, at the age of nine, playing consecutively the boy Mamillius in Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream — rising out of the ground on a mushroom—and Prince Arthur in King John. She attracted the favorable attention of Queen Victoria, who thought she played Puck “delightfully,” and of the Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, better known to posterity as Lewis Carroll. (The German novelist Theodor Fontane—not quoted by Holroyd—was in a minority in finding her “altogether intolerable: a precocious child brought up in the true English manner, old before her years.”2)

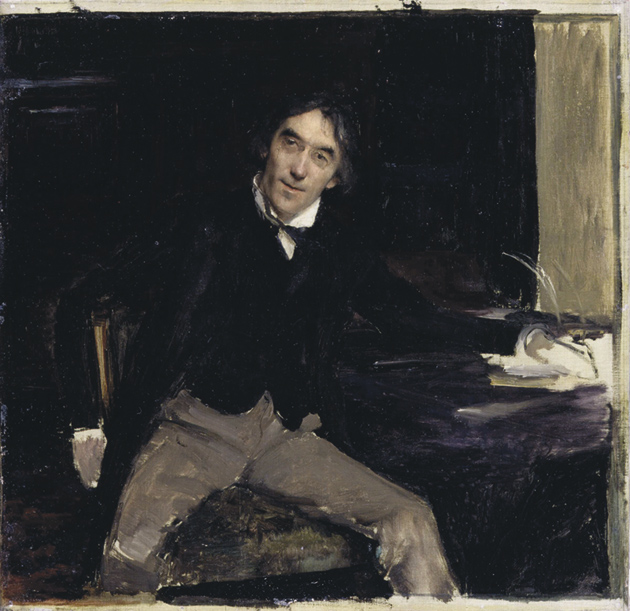

As she grew into adolescence she developed not only into a great beauty but also into a charismatically enchanting personality, an epitome of womanhood who inspired adoration in generations of admirers both on stage and off. Well before she was twenty she was moving freely in fashionable artistic and intellectual circles. One of Julia Margaret Cameron’s finest photographs bears witness to her teenage beauty, as do a number of paintings by Watts, including an astonishingly sensuous, bare-breasted portrait of her as the title character of The Wife of Pluto. Both are reproduced in Holroyd’s appropriately illustrated and carefully indexed book.

Advertisement

Terry and Watts’s courtship was curious. With her sister Kate, also a distinguished actress, the teenaged Ellen had visited Watts’s home to have their joint portraits painted. One day, she later wrote to Bernard Shaw,

He [Watts] kissed me—differently—not much differently but a little, and I told no one for a fortnight, but when I was alone with Mother…I told her…I told her I must be married to him now because I was going to have a baby!!!! I was sure that kiss meant giving me a baby.

And married to him she was, though no baby followed. Maybe Watts—some three times as old as Terry at the time they married—reserved his sensuality for his art.

The marriage was not a success. Within a year friends and relatives had torn them apart, Ellen receiving a generous allowance from Watts for so long as she led “a chaste life” and provided she did not return to the stage. In fact the money continued to be paid for years after both conditions had been broken.

Ellen loved Watts in her way, and she was to love Godwin even more. For several years they lived an idyllic life, Ellen looking after their country cottage and driving her lover in a pony and trap to catch the train to London where he pursued his profession as architect. Their daughter Edith was born in 1869, their son Edward Gordon in 1872. But her liaison with Godwin, and the births of their children, damaged her social standing. Carroll, who also had photographed her as a teenager, dropped her acquaintance, and even her parents did not visit her at home.

In 1874, through a chance encounter with an old friend, the playwright Charles Reade, while he was out hunting, Ellen received a generous offer to return to the stage. She not only accepted but made a huge success. After this her career as an actress was assured. Godwin designed, at great expense, a production of The Merchant of Venice in which she played Portia, laying the foundations of her career as one of the greatest of Shakespearian actresses. For the first time, she was later to write, “I experienced that awe-struck feeling which comes, I suppose, to no actress more than once in a lifetime—the feeling of a conqueror.”

But as Holroyd writes, “Everyone was in love with her except the man she loved.” After the play closed, she and Godwin parted. Six months later he married his young assistant. Only divorce from Watts could regularize her position, and this came about, with his generous help—he paid the costs himself—in 1877. In the same year Ellen herself remarried, this time to an actor, Charles Wardell, known professionally as Charles Kelly. But Terry never settled into domestic stability. Kelly was to become an alcoholic, Terry’s relationship with Irving was the subject of much gossip, and in 1907—after Irving had died—she married another actor, James Carew, who was nearly thirty years her junior. They separated amicably some three years later.

If in spite of all these irregularities Ellen achieved acceptance and indeed adulation in late Victorian and Edwardian society, it was as a result of her genius as an actress, of her professional partnership with Irving, and by sheer force of personality. Nevertheless her past haunted her. Late in her life “Ellen’s name had never appeared on the honours list because, it was supposed, she had led so wild a life: two illegitimate children, three husbands and dubious relationships with Henry Irving and other actors,” and it was not until 1925, when she was almost eighty, that she became a Dame of the British Empire. Even then it was partly in response to dismay that an American-born actress, Genevieve Ward, had become the first woman of the theater to receive the award.

Henry Irving, too, led a checkered private life. Less of a natural performer than Ellen, he had struggled against great odds—poverty, opposition from a mother who believed that actors were automatically damned, a stammer, a poor physique, and a strange gait—to turn himself into an actor. At the age of thirty-one he married Florence O’Callaghan, a formidable lady of social pretensions who was said to have read no book except Burke’s Peerage, rather often. They had two sons but were already drifting apart before the crunch came in 1871, after the opening performance of Irving’s first sensational success in the melodrama The Bells, which he was to play for the rest of his career. As they were driving home, at the very spot where he had proposed to her, Florence asked the exultant actor one of the most supremely tactless and ill-timed questions ever addressed by a wife to a husband: “Are you going on making a fool of yourself like this all your life?” Irving stopped the carriage, “got out, and walked off into the night.” They lived apart for the rest of their lives, but never divorced, which may have helped Irving to escape some of the social stigma that attached to Ellen.

Advertisement

He was helped, too, by the great artistic and financial success that his career as actor-manager soon brought him. He lived lavishly, mingled with the great and the good, lectured and speechified, was accepted as a member of several of London’s most exclusive clubs, gave parties vying in relative ostentation with those of today’s pop stars, had his portrait painted by eminent artists, and performed by command of the Royal Family at Windsor Castle. In America he and Ellen Terry attended presidential receptions. The climax came in 1895 when he became the first actor to receive a knighthood. Florence, in spite of their estrangement, was not displeased to become Lady Irving.

Irving was not an intellectual actor. He performed in many unworthy plays, offered no encouragement to the more serious dramatists of his time, thus incurring the wrath of Bernard Shaw, and failed disgracefully to give Ellen Terry enough roles that were worthy of her. He refused to put on As You Like It although she longed to play Rosalind. But in the roles that suited him he was unquestionably a genius, and he was a great showman. His reputation among intellectuals depended mainly on his series of productions starring himself in plays by Shakespeare. He had relative failures such as Romeo, Malvolio, and Othello. But Hamlet, Shylock, Iago (alternating as Othello with his great American contemporary Edwin Booth), Richard III, Macbeth (in which, wrote Terry, who in spite of her lack of formal education had a natural gift for words, he looked “like a great famished wolf”), Lear, and Cardinal Wolsey provided him with some of his greatest successes.

As a director of Shakespeare, however, he looked backward to the days of Charles Kean and Samuel Phelps rather than forward to the experiments of William Poel and Harley Granville Barker. Though he was apt to build up his own roles, otherwise he cut the texts savagely, omitting substantial parts of The Merchant of Venice and even on occasion the entire last act (in which Shylock does not appear) to make way for a sentimental afterpiece starring Terry. He cut about 40 percent of Hamlet, and, more understandably, parts of Henry VIII (which Holroyd oddly says is “a short play”; in fact, it is among the dozen or so longest). He invested enormous amounts of money in scenery of great elaboration and beauty, in specially composed music, and in costumes such as the robe covered in green beetle-wings that Ellen Terry wore in Sargent’s magnificent portrait of her as Lady Macbeth.

He died in harness, as he wished, in a hotel foyer shortly after speaking the last words—“Into thy hands, O Lord, into thy hands”—of Becket in Tennyson’s play of the same name. He was accorded a funeral of state dimensions, his great coffin paraded through the streets of London and carried in Westminster Abbey by fourteen eminent pallbearers. But as Holroyd reveals in one of those narrative touches of which he is a master, the body had already been cremated: “The solemn burden which had passed laboriously through the streets of London and been carried up the aisle was a stage prop.”

It is paradoxical that although Ellen Terry’s son, Gordon Craig, became one of the most innovative theatrical figures of the twentieth century, he was nevertheless one of the conservative Irving’s greatest admirers, regarding him as his “master,” as he shows above all in his book Henry Irving, of 1930. His description of Irving in The Bells is a masterpiece of evocative prose. Craig led an unstable life, flitting from one European country to another, living sometimes in poverty, at other times in affluence, drawing, designing, teaching, producing plays and masques, making woodcuts and engravings, writing, publishing his magazine The Masque, experimenting with marionettes (so much more biddable than human actors), and reviewing books. I remember reading a piece when it first appeared in, I think, The Spectator, in which he mischievously suggested that Shakespeare’s “Dark Lady” sonnets are addressed to the poet’s black cat.

Craig’s most important work in the practical theater was his collaboration with Stanislavski on a Moscow production of Hamlet, which opened triumphantly in 1912 after three years of preparation, and which subsequently had over four hundred performances. The system of screens that Craig designed for it had a revolutionary impact that continues to be felt today. The 1930 Cranach Press edition of Hamlet, for which he did over 150 woodcuts forming a consecutive commentary on the text, is one of the most highly prized products of private printing presses of the twentieth century. Craig’s most influential book, On the Art of the Theatre, published in 1911, is a seminal work that inspired generations of students and practitioners.

For all his oddities, his infidelities, and his shameful neglect of his children, Craig had a rare capacity to inspire devotion in a sequence of wives and mistresses. He begot thirteen children by eight different women. One of the great loves of his life was the American-born dancer Isadora Duncan. He lived with and off her for a while, drove her to attempt suicide, and they had a daughter. Late in life he helped to support himself by selling their letters to the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. He required a later mistress, Daphne Woodward, to take off all her clothes when she took dictation even though “she protested that she felt ‘silly’ sitting naked with a notebook on her lap.” His mother supported him generously for as long as she could, and in his last years he lived partly on handouts from admirers in the theatrical profession. But like Irving and Terry before him he too was to be honored, with the rare distinction of a Companionship of Honour.

As Holroyd admits, “beside her radiant mother, and in contrast to her mercurial brother,” Craig’s sister Edy was liable to appear “a shadowy figure.” Nor does she come across as one of the more attractive figures in this book. Perhaps this is partly because the children’s father, Godwin, in advance of his time in being impatient of gender distinctions, wished the boy to be “soft and gentle” but Edy “hard as nails.” She was supposed to “brace up” her little brother, who was frightened of the dark, hitting him on the head with a wooden spoon as she exhorted him to “be a woman !” To some extent her career as an adult was overshadowed by her mother, with whom she had a complex relationship, but she was active as an actress, a theatrical costumer and director, a suffragette, and a producer of pageants, working in many parts of England as well as in London. Shaw, with his characteristic love of paradox, said that “Gordon Craig has made himself the most famous producer in Europe by dint of never producing anything, while Edith Craig remains the most obscure by dint of producing everything.” Holroyd puts it more tolerantly:

Ted, crowning himself a once-and-future king at a court that was yet to be created, dreamed of carrying out a Utopian revolution from beyond the contemporary horizon. Edy, with no theatre of her own, was responsible for staging 150 plays…over a decade. Her brother, though producing no plays with his platoon of marionettes in a crumbling arena, brought about a lasting change in theatre production.

Edith has the distinction of having directed the first modern production of John Webster’s tragedy The White Devil. and has been suggested as a model for Miss La Trobe in Virginia Woolf’s novel Between the Acts. Her career is under reassessment by feminist historians of the theater. For much of her life she lived with Christabel Marshall, who preferred to be known as Christopher St. John, and Clare (Tony) Atwood, and the three of them dominated the sad decline of Ellen’s last years. They seem to have behaved poisonously to her over her marriage to James Carew—he referred to them as “those bloody women”—and Gordon Craig was of the same opinion, though he was reconciled with his sister at their mother’s death. St. John helped to edit Ellen’s enchanting memoirs, not always to their advantage.

Holroyd’s preeminence as a biographer of writers and artists working between the middle of the nineteenth to the middle of the twentieth centuries—Bernard Shaw, Augustus John, Lytton Strachey—rests partly on the thoroughness of his archival research, fully witnessed by the “Outline of Sources” listed here, and on his mastery of the historical background. He has superb organizational skills, evinced by the unfailingly lucid intertwining of diverse narratives in this book. He possesses to an unusual degree the quality, difficult to define but so welcome when it occurs, of readability. His sentences flow with easy, rhythmical grace.

Unlabored stylistic felicities abound, and Holroyd has a novelist’s eye for significant detail. Ellen’s understudy as Mamillius, who features nowhere else in the story, is characterized as “a little girl, with eager eyes.” “Before long she [Mrs. Prinsep, Watts’s patron] had uprooted him from his studio and repotted him at her house in Chesterfield Street.” A play by Laurence Irving entitled Godefroi and Yolande was judged unsuitable for performance at the Lyceum in spite of “such exuberant stage directions as: ‘Enter a chorus of lepers.'” “Into whichever room” one of Edy’s less interesting friends walked, “peace would break out like a plague.” Always humane, never oversolemn or judgmental, Holroyd has an entertainer’s appreciation of the picturesque and revealing anecdote. When Gordon Craig was a small boy, known as Teddy, “on arriving at a railway station as the train was pulling out, Teddy was heard to shout: ‘Stop the train—stop the train—this is Miss Terry’s son.'” And after Terry had finished the first part of a recital in Melbourne, “she was presented with flowers, the band struck up ‘God Save the King,’ and the audience, thinking the entertainment over, left the theatre.”

A Strange Eventful History crowns, but we must hope does not conclude, the career of a great biographer.

-

1

Great Historical Shakespeare Recordings, two CDs (Naxos AudioBooks, 2000). The first of these CDs also includes recordings of other actors who figure in Holroyd’s book, including Edwin Booth, Henry Irving, Johnston Forbes-Robertson, and Herbert Beerbohm Tree.

↩ -

2

Theodor Fontane, Shakespeare in the London Theatre, 1855–58, translated by Russell Jackson (London: Society for Theatre Research, 1999), p. 46.

↩