PAR/Marc Domage

Pablo Picasso: Buste, November 21, 1970. John Richardson, curator of the exhibition at the Gagosian Gallery, singled out this painting as his favorite. ‘It’s very spooky, almost ghoulish,’ he told The New York Times. ‘At the time Picasso had been working on a painting of a black bullfighter, but this is a self-portrait. He clearly intended to have a magic element in his work.’

The popular mythology of creative genius depends on beloved stereotypes of the artist in youth and old age: the misunderstood upstart who forces us to see the world afresh; and the revered sage who shows us depths of insight attainable only through a lifetime of hard-won experience. Thrilling though it is to watch a young contender take the world by storm, nothing heartens cognoscenti of a certain age more than an established artist whose last works—exemplified by Beethoven’s transcendent Late Quartets, Rembrandt’s soul-baring self-portraits, and Matisse’s supernal gouaches découpés—convey what Edward Said, in his posthumously published meditation On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain,1 described as “an unearthly serenity.”

But one man’s serenity is another’s senility. It is widely held that Titian underwent a late-life transformation. But a 1990 traveling retrospective on the Venetian master who painted till he dropped from the plague in his late eighties prompted Francis Haskell to wonder, in these pages, if the late Titians hailed by some as audaciously simplified had in fact been unfinished.2 Among artists of our own time, no body of work has polarized opinion more than the pictures churned out by Willem de Kooning after he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and until he could no longer hold a brush. Painted with pigments chosen by assistants, de Kooning’s increasingly vacant agglomerations of unresolved squiggles were touted by opportunistic dealers and complicit curators with euphemisms close to what the literary critic Barbara Hernnstein Smith has called “the senile sublime,” though perhaps “the dross of dementia” is nearer the mark.

Just as the career tangents of even the greatest artists follow no uniform pattern, not all final masterworks conform to popular notions of geriatric nirvana. For example, Rossini’s Péchés de vieillesse (“sins of old age”) of 1857–1868—the fourteen-volume cycle of scintillating bagatelles through which the leisure-loving rentier returned to composition and revisited every aspect of his long-idle virtuosity—may offer no glimpses into eternity, but prove that there are several ways to go out in one final burst of creative glory.

From the outset, the reception of the late work of Pablo Picasso—who died in 1973 at the age of ninety-one—was far from enthusiastic, and ranged from faint praise for his undeniable industriousness to mutterings that the old man had lost it. Those doubts were fed by a trio of shows held in Avignon’s Palais des Papes in 1970, 1971, and 1973. Each omnium gatherum exposed hundreds of new pieces in indigestible overload exacerbated by too-close groupings in too-cavernous medieval chambers ill-suited for the display of contemporary art. The seemingly unedited profusion of works reflected Picasso’s own apparent inability to discard anything he made. But Picasso, the boy wonder of all time, was never one to second-guess his genius and seems to have believed, “Who am I to destroy what God’s gift has allowed me to create?”

Critics took a less sanguine view than he did. One might have expected support from Robert Hughes, that avid exponent of bravura brushwork and rich impasto. But even though late Picassos are awash with ripples, eddies, and whirlpools of thick, luscious, lovely, painterly paint, Hughes’s Time review of the third Avignon exhibition delivered a devastating verdict:

These are, after all, the last Picassos. They are also the worst. It seems hardly imaginable that so great a painter could have whipped off, even in old age, such hasty and superficial doodles.

However, no one was more savage (and authoritative) than the longtime Picasso advocate and collector Douglas Cooper, who became John Richardson’s lover in 1949 and brought the twenty-five-year-old Englishman into the artist’s inner circle, where Richardson remained well after his mentor was banished. Within weeks of the artist’s death, Cooper—still seething over his expulsion from Picasso’s Eden after a self-destructive plea to Picasso on behalf of the painter’s estranged children—wrote a vengeful letter to Connaissance des arts in which he denounced his erstwhile idol’s swan song as “incoherent scrawls executed by a frenetic old man in the antechamber of death.” Frenetic, yes; incoherent, no: Picasso’s relentless work ethic is aptly characterized by Dakin Hart in his thought-provoking “Mosqueteros” catalog essay as “death-defying sharklike motion forward.”

Slowly, though, opinion began to turn. By the time of the Guggenheim Museum’s 1984 Picasso retrospective, Hughes allowed in Time that

Advertisement

Not even the most hard-bitten viewer can contemplate this oeuvre without a degree of awe—a sensation not always identical with aesthetic pleasure. No doubt about it, Picasso painted many bad and some flatly absurd pictures at the end of his life. But the good ones are so good, and in such a weird way, that they utterly transfix the eye….

Over the ensuing quarter-century, favorable opinion continued to rise steadily, and prices for late Picassos enjoyed a sharp upturn after the millennium, an increase not wholly attributable to the rising art market or the growing paucity of earlier Picassos. Indeed, the new constituency for late Picasso had much to do with new directions in avant-garde painting since his death, which made many people look quite differently at his startling final output.

If there is any flaw in “Picasso: Mosqueteros”—the survey of more than a hundred of the master’s paintings and prints from 1962 to 1972, on view at the Chelsea branch of the Gagosian Gallery in New York—it is its organizers’ overeagerness to reposition these long-disdained valedictory works on the Beethovian rather than Rossinian slopes of Parnassus. This revisionist placement (perhaps prompted by the age-old bias that grants higher status to tragedy than comedy) seems wholly beside the point, given how conclusively John Richardson—the show’s curator and the celebrated Picasso biographer—establishes the importance of this once-disparaged coda to his subject’s monumental career beyond likelihood of refutation.

In the accompanying catalog (a sumptuous production certain to become a staple of the Picasso literature), Richardson proclaims—a bit too optimistically—that “Picasso did achieve a Great Late Phase.” What is manifest from the curator’s quite possibly unsurpassable selection of pictures (many borrowed from descendants of the artist, and his grandson Bernard Ruiz-Picasso in particular, although it remains unclear how many, if any, are actually for sale here) is that even though the Artist of the Century did indeed have quite a few great last days, a number of great last weeks, and even the odd great last month, they don’t quite add up to a Great Late Phase, at least as that term is commonly understood.

Again this hardly matters, because Picasso was uneven throughout his entire career (albeit to varying degrees), even during peak phases. A number of his Analytical Cubist compositions of 1912 are boring and pointless; after a while his brownish, fragmented bottles are hard to distinguish from his brownish, fragmented faces without the help of a mustache or “VIN” label. His rightly acclaimed “Sleeping Women” series of 1932 included several duds, just as he also coasted in some of the hundred-plus prints for his glorious Suite Vollard, another highlight of that wonder decade.

Ironically, the artist renowned for his Blue and Rose periods was in fact never much of a colorist, a deficiency reflected in his abiding envy of the one contemporary he could never challenge in that regard—Matisse, the hands-down chromatic champ of Modernism. Picasso’s superhuman gift for draftsmanship might have made him lazy about pursuing the full potential of color. It was not unusual for him to build a composition by first outlining figures and objects in black and then filling the interstices in a perfunctory manner that can put one in mind of a museum-shop coloring book.

Thus the biggest surprise of “Picasso: Mosqueteros” is its evidence of a coloristic metamorphosis that overtook the monochromatically inclined master in his supposed dotage. A good dozen of the fifty-two oil paintings at Gagosian fairly jump off the walls (whose majestic spatial arrangement was worked out by the rising architectural star Annabelle Selldorf). Picasso’s off-kilter color combinations evoke the masters of Mannerism just as surely as the show’s namesake motif of musketeers evokes a recurrent character in the work of Hals, Velázquez, and Rembrandt, touchstones and sparring partners of Picasso’s old age.

The exhibition catalog reveals intriguing sources for this imagery beyond the illustrated monographs Picasso consulted during the years when he stuck close to his houses in the south of France. As Richardson points out, the artist’s sources were both high and low: “Picasso was a movie buff and is unlikely to have missed Bernard Borderie’s 1961 movie Vengeance of the Three Musketeers,” and “whether or not he had actually seen The Night Watch…in the Rijksmuseum, Picasso had slides of it projected onto his studio walls, thus enabling Rembrandt’s militia men to enter into another artist’s imagination.” (Slide projection would become a standard practice among 1980s artists including David Salle, but there is no evidence that Picasso, like those later painters, traced such images directly onto his canvases.)

But above all it is Picasso’s belated effulgence of color—hardly attributable to the murky tonalities of Rembrandt or the predominant black, white, and gray of Hals—that makes this show a revelation. The high-keyed chromatic juxtapositions of Picasso’s Homme à la pipe of November 7, 1968, bring to mind (if not with paint- chip exactitude, then closely enough) the clangorous combination of poison green, bismuth pink, and icy aquamarine in Pontormo’s Deposition of circa 1528 in the Capponi Chapel in Florence. The palette Picasso employed for his Tête de matador of November 17, 1970—with its mottled slate-and-mauve face, persimmon-hued headdress, and greenish-gold ground—summons up the rust, marigold, tangerine, and teal silk billows that envelop Zurbarán’s Saint Casilda of 1638–1642 in the Prado.

Advertisement

But by no means was it all homenajes to the Old Masters once Picasso indulged his newfound obsession with color. Perhaps the most delicious picture in the Gagosian overview is his Torero of October 16, 1970, a sly spoof (whether specifically intentional or not) of modern-day matador paintings on black velvet, the sort of touristic kitsch the aged master might have spotted in souvenir shops on his strolls to the arena in Arles, where he reconnected with his youthful passion for bullfighting. In this picture, the toreador’s yellow-bespangled green “suit of lights” and tasseled orange cap take on a Day-Glo intensity against the flat, jet-black background. His magniloquent posturing and googly-eyed visage imbue the picture with an irresistible mixture of foolhardy bravado and touching fearlessness needed by practitioners of a blood sport that Picasso identified as having much in common with his own high-risk line of work.

A consensus among art-world regulars has centered around one work as the star of “Picasso: Mosqueteros”—the oil-on-canvas Buste of November 21, 1970, which Richardson himself singled out in a New York Times in-terview. This haunting imaginary portrait of a bust-length mustachioed bravo topped with a fanciful green hat and caparisoned in a black-patterned red cloak and white ruff is dominated by one coal-black eye thickly encircled in poker-hot orange, which juts downward like the handle of a lorgnette. It’s a disturbing, unforgettable image, and its unnerving power seems to confirm a key principle of Picassology set forth by the exhibition’s curator.

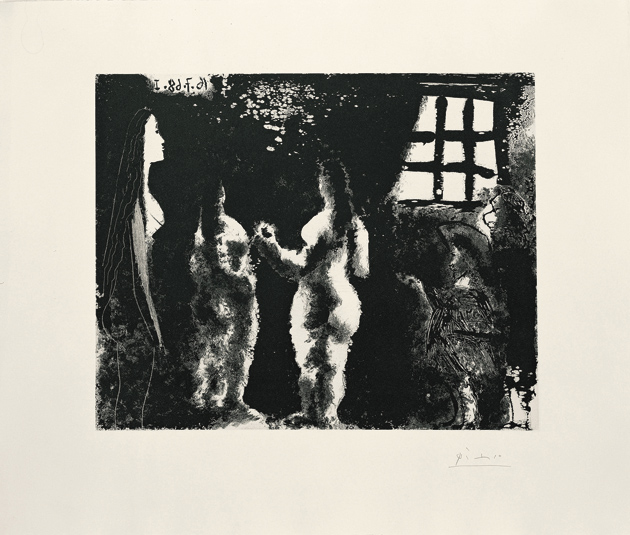

Private Collection/Marc Domage

Pablo Picasso: En pensant à Goya: Femmes en prison, June 16, 1968. According to Martin Filler, ‘This sugar-lift aquatint with grease—the latter component causing the seepage of ink that defines the undulating back of the central nude woman with such palpable sensuousness—speaks of absolute mastery on every level, from the observational and manual to the conceptual and spiritual.’

Richardson has insisted that the artist considered the things he created literally magic—as opposed to metaphorically magical—repositories for supernatural projections and embodiments of all sorts: good-luck charms, shields meant to ward off evil, expiatory offerings, voodoo dolls, and incantatory fetish objects, not unlike the original functions of the African tribal artifacts he collected soon after his arrival in Paris. At no point in his eight-decade career was that shamanistic intent ever clearer than it is in this final body of work, which helps explain why even when individual examples do not entirely work—for example, the large and imposing Homme assis au fusil of September 17, 1969—they nevertheless create an effect whose magnetism is not easily dismissed.

One’s prior expectations to the contrary, only a few of the paintings assembled at Gagosian are outright failures, and only a small handful can be termed daubs—alas the only word befitting a pair of weak profiles entitled Le peintre au XVIIème siècle and Peintre au visage vert, both of 1967. On the other hand, among the show’s fifty-seven prints (including aquatints, etchings, and hybrids of multiple graphic techniques) there is nary a loser in the lot. The technical command Picasso demonstrated in the prints of the 1930s that comprised his Suite Vollard not only remained intact throughout the 1960s but clearly deepened, as proven by perhaps the finest among the late graphics, En pensant à Goya: Femmes en prison of June 16, 1968. This sugar-lift aquatint with grease—the latter component causing the seepage of ink that defines the undulating back of the central nude woman with such palpable sensuousness—speaks of absolute mastery on every level, from the observational and manual to the conceptual and spiritual.

Richardson is the undisputed doyen of Picasso scholarship for reasons beyond his survival among the last living links to the man as synonymous with modern art as Rembrandt is with Old Master painting. He is also among the few remaining exemplars of old-school high-style connoisseurship, a comparative, qualitative method that emerged in Enlightenment Europe, flourished until the late twentieth century, and insisted that the work of an artist should be understood in relation to his situation, his milieu, and his mind. For Richardson this has entailed a prodigious effort that is far from done. But seeing, especially in regard to Picasso, is believing. In a 1932 conversation with the Greek- born art publisher who went by the pseudonym of E. Tériade, the artist spoke in terms that reflected his well-known view of himself as epicenter of a personal universe. “When you come right down to it, all you have is your self,” he asserted. “Your self is a sun with a thousand rays in your belly. The rest is nothing.”

Nearly four decades after that remark, Picasso was much closer to ultimate nothingness when he created Profil of December 13, 1970, an oil on corrugated cardboard that struck me more viscerally than any other picture in “Picasso: Mosqueteros.” This left-facing profile of yet another Van Dyck–bearded personage is unlike any other in the show thanks to the blood-red rays that emanate from the monumental head and stream outward into some light-washed great beyond. These veins fairly throb with the liquid of the life force, and flaunt the prodigious vitality Picasso poured into his work unto the very last drop.