When Alexander Herzen came to London in 1852, an exiled stranger in the richest city on earth, he found its indifference reassuring. The place was dreary, unhealthy, monstrously unjust but also unchanging:

One who knows how to live alone has nothing to fear from the tedium of London. The life here, like the air, is bad for the weak, for the frail, for one who seeks a prop outside himself, for one who seeks welcome, sympathy, attention; the moral lungs must be as strong as the physical lungs, whose task it is to separate oxygen from the smoky fog….

He missed his wife and small daughters; only his little son Sergei was with him. When Sergei was asleep, Herzen went out to prowl the silent city with its “street-lights without end in both directions,” and leaned brooding over its bridges:

One city, full-fed, went to sleep: the other, hungry, was not yet awake—the streets were empty and nothing could be heard but the measured tread of the policeman with his lantern. I used to sit and look, and my soul would grow quieter and more peaceful. And so for all this I came to love this fearful ant-heap, where every night a hundred thousand men know not where they will lay their heads, and the police often find women and children dead of hunger beside hotels where one cannot dine for less than two pounds.

For over a hundred years after that, exiles and refugees finding their way to London confessed to much the same mixture of feelings. The silent indifference of the English to these foreigners in their midst was inhuman. The poverty, inequality, and privileged arrogance of the place were horrifying. And yet the very fact that nothing much ever changed—the “measured tread” of a deeply conservative, law-abiding society—was somehow calming.

For people who had fled from places where everything old and loved was slithering to destruction, where the rules of every game might change overnight, the continuity of England made the “soul grow quieter and more peaceful”—even the soul of a revolutionary like Herzen. So it was for fugitives from France after the Commune, for the Jewish immigrants from tsarist Russia, and for most of the thousands in flight from the Nazis. In those times, there was only one immigrant group for which the imperviousness of London had no attractions. That was the biggest group of all and the only one to have experienced English colonialism: the Irish.

Now, it seems, everything is different. It’s change, not permanence, that makes London famous. The postwar inrush of Asian and Afro-Caribbean migrants is long-settled, often third-generation British. London has accelerated through ghetto multiculturalism to become one of the most adventurously hybrid cities on earth. And in the last four years, since the first post-Communist nations joined the European Union, a fresh torrent of young job-seekers from Central and Eastern Europe arrived. Nearly a million of them were Polish, many of them now preparing to return home as Poland’s economy strengthens and to invest their earnings in their own small business or farm. Many are highly educated and skilled. But others, especially those from the smaller, poorer countries on the Baltic or in the Danube basin, are neither. Too often, they fall victim to labor contractors and their gang masters, live packed into huts and trailers, and are illegally cheated of their wages.

No systematic attempt has been made to find out what they all think of Britain. But my own impression is that on balance they admire it, with ironic reservations. London is fun, but the prices are just robbery. Work is a harsh sink-or-swim, but hard labor usually does earn good money. The English are selfish and hypocritical, but their casual democracy and their utter disrespect for authority are brilliant. (Lessons learned in Britain by young Polish voters helped to throw out the odious Kaczynski government last year.)

This is the scene that Rose Tremain chooses for her latest novel. England is currently suffering convulsions of anxiety about “immigration.” Part of this is simple xenophobia, a media-driven panic that ignores both the enrichment of daily life brought about by Eastern European energy and skill (the universal “Polish plumber” or builder gushed over at London dinner parties) and the fact that most of these migrants intend to return home. But another part is liberal concern: shock at neo-Victorian dramas of their exploitation, and at the loneliness and victimization that Eastern European migrant workers can encounter.

Fiction about the migrant labor experience in Europe has been around for a long time. John Berger took the subject up in the 1960s, while there has been extensive German writing over the last forty years about the Turks as Gastarbeiter (guest workers) or as settled German citizens. And it’s not as if European migrant workers had avoided Britain before 2004. Once again, the enormous mass of Irish immigrants—just as liable to be exploited, lonely, or victimized—seems weirdly invisible to the English eye. Yet over a million men and women came from Ireland to work in England and Scotland in the twentieth century alone.

Advertisement

It’s a point Rose Tremain picks up. One of her secondary characters (and this novel is marvelous for its secondary characters) is an Irishman named Christy Slane. He is a plumber, a frail and erratic charmer whose boozing has lost him his adored daughter and his coldhearted English wife. For Christy, London is just a place to live and its aboriginals are best avoided. He advises Lev, the Eastern European migrant whose adventures form the novel’s main narrative, not to tangle with English girls:

…You and me, we’re foreigners both. All Angela could say to me when things started to go wrong was “I shouldn’t have married a fucking foreigner.”… I speak the same language. I’ve lived in London fifteen years, but there you are.

Lev comes from a country minutely described but never specified. This country has just entered the European Union, which means that his search for work in Britain is legal. His home is the dilapidated village of “Auror,” abandoned by the world; communism has been replaced by unemployment and corruption, while the sawmill where Lev and his father worked has “run out of trees” and closed. Lev’s beloved wife Marina died a few years ago of leukemia, prevalent in this polluted region, and their small daughter Maya is being brought up by his mother. In order to earn the money to give them something like a life, Lev finally follows many thousands of his countrymen and boards a bus for the long journey across frontiers and seas to England.

On the bus, he is sitting next to a hopeful, vulnerable schoolteacher named Lydia. Herself a “cultured” and well-read city person, she is attracted by this handsome village man, already gray-haired at the age of forty, and makes him reveal more about himself. Lev has been notorious at home as a dreamer, sensitive and yet prey to an inertia that has only deepened since the death of his wife. After the sawmill closed, he has done little but sit around chain-smoking. He would never have summoned the energy to seek work in England if it were not for the bullying of his friend Rudi. Again, both Rudi and Lydia are vivid secondary characters whose appearances and passions bounce up all through the novel. Rudi, the opposite of Lev, is a hard-drinking man of action in this dim corner of Europe; his true love is a huge, battered Chevrolet (“Tchevi”) that he and Lev rescue together and patch up for Rudi to use as a taxi.

After nights and days, the bus arrives at Victoria Coach Station in central London. Lydia goes in one direction, and Lev—knowing nobody, and with almost no English—takes his bag and wanders off in another. There now begins the long tale of misadventure, the serial account of how Lev is humiliated, exploited, jostled, deceived, and in countless ways pushed around, which fills the first two thirds of Rose Tremain’s book.

He has no money beyond a few £20 bills that Rudi, quite wrongly, has assured him will be enough to keep him going for weeks. On the bus, he has already studied the bearded face of Edward Elgar on the banknote, and Elgar—his music, but above all the emblematic story of his rise to fulfillment from a humble provincial music shop—is one of several recurring threads of reference in The Road Home. Lev starts badly by getting himself worked over by a policeman who finds him asleep on a sidewalk. An Indian lady who runs a lodging house is sympathetic, but one night there absorbs most of his money. Desperate, he encounters Ahmed, an Arab kebab-café owner who gives him a micro-job distributing menu leaflets around the neighborhood, feeds him for free, and gives him wise advice. (It’s fascinating, but important to this story, that its large London cast includes not one sympathetic English character, with the single exception of a dignified old lady dying in a retirement home. Decency, mercy, and unselfishness in the “fearful ant-heap” come from two Indian women, Ahmed the Arab, two Chinese gays, a black Cockney girl, Lydia from Lev’s own country, and Christy the Irishman. They contrast with the aboriginals who, though not immune to brief flashes of human feeling, are in it for what they can get.)

Now sleeping rough, Lev appeals to Lydia for help in finding work, and spends one unreal night of luxury with her superior friends in north London. He finds a lodging, settling into Christy’s flat in the bedroom left empty when Christy’s daughter Frankie was taken into her mother’s custody. And he starts work as a dishwasher in a restaurant kitchen, a frantically fashionable eatery whose boss, the celebrity chef G.K. Ashe, terrorizes his cooks and waiters. Lev survives, and his washing-up even wins approval. Then he lets himself be seduced into an affair with Sophie, the plump, pretty vegetable chef. For a moment, Lev seems to be in command of a situation. But gloomy warnings about English girls from Christy and Rudi turn out to be well founded. Sophie is a happy “ladette,” a binge-drinker who is also helplessly thrilled by passing “celebs” on London’s cultural scene. Lev soon finds he is just an episode, as she lets herself be acquired by the glamorous Howie Preece, a Young Brit conceptual artist who patronizes the restaurant.

Advertisement

Rose Tremain takes a savagely bleak view of English intellectual fashion. In a scene set at the Royal Court Theatre, she imagines a truly frightful new play that “boldly” explores onstage sex with children and inflatable dolls, and she recounts the play’s action on page after page. At the end, a baffled and disgusted Lev gets into an argument at the bar. He tries to strangle Sophie as she defends the play, but Howie Preece overpowers him and throws him out.

It’s the end of the affair, but not the end of Lev’s downfall. When he gets drunk and is arrested for kicking trash bins in the street, Lydia reappears, prim and disapproving, to pay his fine and bail him out. Back at the restaurant, G.K. Ashe fires Lev, worried that he will upset Sophie and disturb her profitable connection with Preece and his circle. Lev has almost hit bottom now. When Sophie comes to his room on an ambiguous “let’s-stay-friends” mission, he rapes her.

But then the novel changes gear. In the next section, Lev has quit London and has sunk to the lowest rung of the migrant ladder: contract gang labor on vegetable and fruit harvests in the vast fields of East Anglia. And yet this is the turning point of the story, the moment at which light begins to dawn on his wretched life. He gets to know the one attractive English character in the book: the stout, lonely asparagus farmer Midge, who—like him—mourns not only the loss of a wife but the loss of a past (“The English used to love the land…. Don’t know where that love went”). He makes firm friendships with the other laborers, and begins to read and to reflect.

The terrible news comes to him that his home village is to be drowned by a new dam. Auror will vanish, and all its people will be forced to “relocate” to the grubby town of Baryn. Rudi, like Lev’s mother and daughter, feels that their world is coming to an end. And yet it’s now that Lev, as he works in the asparagus fields, has a vision. It’s a dream of how he might return to his family, reverse their fortunes, and at last gain control of his own storm-driven life.

Reviewers shouldn’t give everything away. The last third of The Road Home is the narrative of Lev’s battles, setbacks, compromises, and triumphs as he fights toward the realization of “The Dream.” It’s enough to say that this narrative jolts the whole novel into convincing movement with a strong story to tell. Up to then, though, the book—for me—was weakened by a sense of unreality, even of contrivance.

The weakness certainly isn’t in the detail. Rose Tremain has done a great deal of patient research, from finding her way through the culture of restaurant kitchens to the economics of asparagus growing. She has talked to experts on old Chevrolet motors and to Polish migrant workers in the fields of eastern England. And neither does the weakness lie in the cast that Tremain recruits for her story. She has created, as I have said, a gallery of unexpected, often very moving, ancillary characters. But there is a problem with The Road Home, and the name of the problem is Lev.

The first little warning light goes on when Lev is denied a homeland. He comes from a dilapidated somewhere that has wriggled itself under the wire and into the European Union. He has a landscape, complete with goats’ milk and dying forests and women in head-scarves and cheap vodka, but he isn’t allowed to have a nation. The trouble with this approach is that there is no such place as “Eastern Europe,” no single goose-infested zone stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea in which poverty and corruption obliterate all distinctions. What’s specific about that part of Europe is precisely its damned specificity. It matters enormously whether you speak Ruthenian or Polish, Estonian or Russian; it matters whether you were born Orthodox, Uniate, or Roman Catholic, and what your ancestors did in the Tatar, Swedish, or Nazi invasions. In that part of the world, such stuff makes individual identities. But Lev has no such identity, merely longing to escape “the past” and its myths and the life his father led.

There are certainly legions of young people working in Britain and Ireland who look back on their fathers’ tales of foreign invaders and heroic partisans with boredom. Getting away from that burden of patriotic awe was important to them. And yet the final charm to ward off the West’s drowning waves of anonymity is so often nationhood. “Whatever they do to me, I will always be a Slovak, or a Lithuanian, or a Tatar….”

Lev doesn’t have this talisman. The reader learns an enormous amount about him, about his dreaminess, his sensual delight in smoking, his care with his clothes, his lurches into violence when he thinks that he is being mocked. But the element that brings all those traits together into a three-dimensional personality is missing. Think of the Rabbi Loew in Prague, who popped his magic shem into the forehead of the Golem in order to bring him to life. Lev lacks a shem. To know that Lev was (as his landscape and habits might suggest) from Bulgaria, or from the hills of western Ukraine, would have helped to make him real.

The Road Home seems to belong to a very large and very old family of fiction: “the unspoiled country lad comes to town.” It’s a respectable clan. Its ancestry runs back to the classical world, but its true floruit was the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in Western Europe and America. There it advanced Enlightenment values: the notion that natural virtue resided in rural places, where men and women grew up in touch with universal moral laws that included altruism, piety, and sensual self-restraint. Counterposed to this was the city, the unnatural metropolis where selfishness, grotesque luxury, debauchery, and greed were flaunted on every street. The purpose of this literature was to display the immorality of modern urban life through the wide eyes of some innocent who jumps down from the coach with all his or her moral sensibilities still in their proper place.

Most of these books were written, of course, by well-off townies. Candide is a member of the family. So, in effect, is Fanny Hill. Tobias Smollett and Henry Mackenzie (The Man of Feeling) both used the form. Another example is John Galt’s comic The Ayrshire Legatees (1820), although here the provincial Scottish family in London is not so much representative of natural decency as of small-town gullibility. With this, especially in the nineteenth century, came a tepid flood of Christian tract fiction, dramatizing the impact of the modern Babylon on the purity of boys and girls as they are sacrificed to its needs and lusts. And not only on young English or Scottish provincials. Uncorrupted visitors from distant lands—Oriental travelers or African slave girls —could serve the same dramatic purpose: to register their astonishment.

It’s a genre that endures and thrives in our own times. In her experiment with it, Rose Tremain has plenty of contemporary company: Kiran Desai’s prize-winning The Inheritance of Loss, for example, unmasks Manhattan through the eyes of a hard-pressed Indian kitchen boy. But it’s also a genre with its own technical pitfalls. A writer has to decide what the subject of such a book really is: the wide-eyed observer or the scene being observed? Lev or London? The most convincing answer in almost all these fictions is that it’s the scene, the outrageous Babylon, which is under study. The observer is a device or a lens, whose reactions have to be a bit distanced if they are not to grow monotonously priggish or get in the author’s way. Candide himself is a caricature, whereas the world he stumbles through is seriously recognizable.

This is where Tremain has tripped herself up. She is a practiced and fastidious writer, famous for craft. So when the reader hits sentences like “Howie’s slug-white jowls dug themselves into a leer” or “The air he was forced to breathe had about it the overwhelming gamey perfume of success,” it’s hard to realize that they were written by the author of the exquisite The Way I Found Her (1997). It’s not that Tremain has somehow lost her talent; far from it. It’s that there’s a crisis deep in the engine room of her novel, steaming up the language she uses around the character of Lev. And the crisis has come about because Tremain has dodged that decision about subject and tried to make Lev and London equally “real,” the joint focuses of her novel.

In a recent interview, she said: “I get letters now from people saying they look at the [immigrant] builders next door in a different way. Because they don’t just see a group, they see Lev. And that’s exactly what I hoped might happen.” But in the same interview, she says that “the culture we swim in…to an outsider’s eye does look extremely vulgar and shallow.” In this contest of emphases, Lev is the loser. The Road Home is primarily a fearsome panorama of the corruption of twenty-first-century London, a Great Wen dominated by callous fashionistas and supported by the toil of a vast immigrant underclass. Tremain has carefully endowed Lev with all sorts of interesting traits, some lovable and some alienating. But London upstages him all the way through until the moment when his own narrative, his “Dream” and his struggle to realize it, takes over the novel.

Is it accurate, this Lev vision of obese, guzzling Londoners who steal from the weak, worship celebrity and wealth, and greet strangers with insults and blows? English kindness and helpfulness have certainly declined, but hardly to the point at which London has become Gomorrah on the Thames or the nightmare Berlin of George Grosz. The “measured tread” of the policeman is less reassuring than it was in Herzen’s day, but most Londoners would still prefer to clutch a police phone number than a gun. The Eastern European immigrants are far less vulnerable than the Afro-Caribbean incomers of the 1950s, let alone the nineteenth-century Irish, and many have successfully worked out ways to exploit their exploiters.

The offense London gives these days is moral and aesthetic rather than social. Rose Tremain makes Lev cover his face and feel sick as two fat men eat hamburgers with fried onions on the London Tube. This sight and smell may be unpardonably coarse for some English writers, but I don’t think it would signal the end of civilization to a boy from Vilnius or Chernivsti.

Tremain seems to share that indomitable English faith that better times are just around the corner behind you: “fings ain’t wot they used to be.” A less conservative argument could be made: “fings” in the near future, especially in London, may actually turn out to be a sharp improvement on the present, with mass immigration largely to thank for it. Still, fairness or accuracy are not the point here, which is conviction. And Rose Tremain’s version of the “fearful ant-heap,” seething with temptations of fame and money, reeking with pretentious xenophobia, is very convincing indeed.

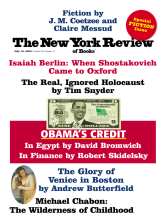

This Issue

July 16, 2009

Advice to the Prince