In response to:

What to Do About Darfur from the July 2, 2009 issue

To the Editors:

I am writing in response to Nicholas Kristof’s review of my book, Saviors and Survivors: Darfur, Politics, and the War on Terror [NYR, July 2].

Nicholas Kristof speculates that I could only have gone to Darfur on officially organized “propaganda tours.” The answer lies in the opening pages of Saviors and Survivors: I went to Darfur as a consultant for the Darfur–Darfur Dialogue and Consultation of the African Union. My job was to facilitate the very civil society meetings that Kristof recommends as one way forward.

Kristof has compiled a list of discrepancies from the Social Science Research Council blog Making Sense of Darfur and suggests that they undercut my account of the working of US government agencies, but in fact they don’t. Congress passed the “genocide” resolution on June 24, 2004, before the State Department–organized research team carried out interviews in Chad. The State Department never published these findings—leading the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to recommend “that the Secretary of State promote greater transparency in any of its future death estimates for Darfur.” When a team member, John Hagan, published these findings independently, the GAO dismissed the claim of about 400,000 dead as an extrapolation from an unrepresentative sample. Hagan repeats that claim in his new book, and Kristof reviews it approvingly. Kristof uses that same unrepresentative sample—the refugee camps in Chad—to generalize about the whole of Darfur, raising doubts about his own conclusions.

Saviors and Survivors focuses on issues that have driven the violence. I point out that this violence began as a drought-driven conflict in 1987–1989, not between “Arabs” and “Africans” but between tribes with homelands and those without. There was a human slaughter, as in 2003–2004, but both the UN Commission (2004) and the ICC (2009) threw out the charge of genocide because those killed were not consciously identified as part of a group.

Saviors and Survivors insists that Africa must draw appropriate lessons from its own history. The League of Nations evoked “Responsibility to Protect” as a doctrine to justify the continued colonization of Africa after World War I. One lesson of Rwanda, a Belgian trust territory, was that there would have been no genocide except for Belgium’s legally enforced racialization of the population. Belgium’s race policies were extreme but not exceptional.

The experience of apartheid South Africa, Mozambique, and South Sudan—and now Zimbabwe and Kenya—shows that the pursuit of criminal justice in ongoing conflicts only exacerbates civil wars, and deepens external intervention. To achieve political reform, the focus needs to shift from perpetrators to the issues that drive the violence. For Kristof, however, any inquiry into the history and causes of violence—as I have done with regard to September 11 and the Rwanda genocide—is to offer an apology for perpetrators.

Mahmood Mamdani

Herbert Lehman Professor of Government Professor of Anthropology

Columbia University

New York City

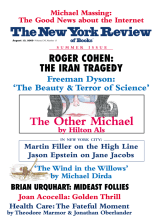

This Issue

August 13, 2009

When Science & Poetry Were Friends

A Very Chilly Victory