22 August 1972

In yesterday’s Sunday Times, a report from Francistown in Botswana. Sometime last week, in the middle of the night, a car, a white American model, drove up to a house in a residential area. Men wearing balaclavas jumped out, kicked down the front door, and began shooting. When they had done with shooting they set fire to the house and drove off. From the embers the neighbors dragged seven charred bodies: two men, three women, two children.

The killers appeared to be black, but one of the neighbors heard them speaking Afrikaans among themselves and was convinced they were whites in blackface. The dead were South Africans, refugees who had moved into the house mere weeks ago.

Approached for comment, the South African minister of foreign affairs, through a spokesman, calls the report “unverified.” Inquiries will be undertaken, he says, to determine whether the deceased were indeed South African citizens. As for the military, an unnamed source denies that the SA Defence Force had anything to do with the matter. The killings are probably an internal ANC matter, he suggests, reflecting “ongoing tensions” between factions.

So they come out, week after week, these tales from the borderlands, murders followed by bland denials. He reads the reports and feels soiled. So this is what he has come back to! Yet where in the world can one hide where one will not feel soiled? Would he feel any cleaner in the snows of Sweden, reading at a distance about his people and their latest pranks?

How to escape the filth: not a new question. An old rat-question that will not let go, that leaves its nasty, suppurating wound. Agenbite of inwit.

“I see the Defence Force is up to its old tricks again,” he remarks to his father. “In Botswana this time.” But his father is too wary to rise to the bait. When his father picks up the newspaper, he takes care to skip straight to the sports pages, missing out on the politics—the politics and the killings.

His father has nothing but disdain for the continent to the north of them. Buffoons is the word he uses to dismiss the leaders of African states: petty tyrants who can barely spell their own names, chauffeured from one banquet to another in their Rolls-Royces, wearing Ruritanian uniforms festooned with medals they have awarded themselves. Africa: a place of starving masses with homicidal buffoons lording it over them.

“They broke into a house in Fran- cistown and killed everyone,” he presses on nonetheless. “Executed them. Including the children. Look. Read the report. It’s on the front page.”

His father shrugs. His father can find no form of words spacious enough to cover his distaste for, on the one hand, thugs who slaughter defenseless women and children and, on the other, terrorists who wage war from havens across the border. He resolves the problem by immersing himself in the cricket scores. As a response to a moral dilemma it is feeble; yet is his own response—fits of rage and despair—any better?

Once upon a time he used to think that the men who dreamed up the South African version of public order, who brought into being the vast system of labor reserves and internal passports and satellite townships, had based their vision on a tragic misreading of history. They had misread history because, born on farms or in small towns in the hinterland, and isolated within a language spoken nowhere else in the world, they had no appreciation of the scale of the forces that had since 1945 been sweeping away the old colonial world.

Yet to say they had misread history was in itself misleading. For they read no history at all. On the contrary, they turned their backs on it, dismissing it as a mass of slanders put together by foreigners who held Afrikaners in contempt and would turn a blind eye if they were massacred by the blacks, down to the last woman and child. Alone and friendless at the remote tip of a hostile continent, they erected their fortress state and retreated behind its walls: there they would keep the flame of Western Christian civilization burning until finally the world came to its senses.

That was the way they spoke, more or less, the men who ran the National Party and the security state, and for a long time he thought they spoke from the heart. But not anymore. Their talk of saving civilization, he now tends to think, has never been anything but a bluff. Behind a smokescreen of patriotism they are at this very moment sitting and calculating how long they can keep the show running (the mines, the factories) before they will need to pack their bags, shred any incriminating documents, and fly off to Zurich or Monaco or San Diego, where under the cover of holding companies with names like Algro Trading or Handfast Securities they years ago bought themselves villas and apartments as insurance against the day of reckoning (dies irae, dies illa).

Advertisement

According to his new, revised way of thinking, the men who ordered the killer squad into Francistown have no mistaken vision of history, much less a tragic one. Indeed, they most likely laugh up their sleeves at folk so silly as to have visions of any kind. As for the fate of Christian civilization in Africa, they have never given two hoots about it. And these—these!—are the men under whose dirty thumb he lives!

To be expanded on: his father’s response to the times as compared to his own: their differences, their (overriding) similarities.

1 September 1972

The house that he shares with his father dates from the 1920s. The walls, built in part of baked brick but in the main of mud-brick, are by now so rotten with damp creeping up from the earth that they have begun to crumble. To insulate them from the damp is an impossible task; the best that can be done is to lay an impermeable concrete apron around the periphery of the house and hope that slowly they will dry out.

From a home improvement guide he learns that for each meter of concrete he will require three bags of sand, five bags of stone, and one bag of cement. If he makes the apron around the house ten centimeters deep, he calculates, he will need thirty bags of sand, fifty bags of stone, and ten bags of cement, which will entail six trips to the builder’s yard, six full loads in a one-ton truck.

Halfway through the first day of work it dawns on him that he has made a mistake of a calamitous order. Either he misread the guide or in his calculations he confused cubic meters with square meters. It is going to take many more than ten bags of cement, plus sand and stone, to lay ninety-six square meters of concrete. It is going to take many more than six trips to the builder’s yard; he is going to have to sacrifice more than just a few weekends of his life.

Week after week, using a shovel and a wheelbarrow, he mixes sand, stone, cement, and water; block after block he pours liquid concrete and levels it. His back hurts, his arms and wrists are so stiff that he can barely hold a pen. Above all the labor bores him. Yet he is not unhappy. What he finds himself doing is what people like him should have been doing ever since 1652, namely, his own dirty work. In fact, once he forgets about the time he is giving up, the work begins to take on its own pleasure. There is such a thing as a well-laid slab whose well-laidness is plain for all to see. The slabs he is laying will outlast his tenancy of the house, may even outlast his spell on earth; in which case he will in a certain sense have cheated death. One might spend the rest of one’s life laying slabs, and fall each night into the profoundest sleep, tired with the ache of honest toil.

How many of the ragged workingmen who pass him in the street are secret authors of works that will outlast them: roads, walls, pylons? Immortality of a kind, a limited immortality, is not so hard to achieve after all. Why then does he persist in inscribing marks on paper, in the faint hope that people not yet born will take the trouble to decipher them?

To be expanded on: his readiness to throw himself into half-baked projects; the alacrity with which he retreats from creative work into mindless industry.

16 April 1973

The same Sunday Times which, in among exposés of torrid love affairs between teachers and schoolgirls in country towns, in among pictures of pouting starlets in exiguous bikinis, comes out with revelations of atrocities committed by the security forces, reports that the minister of the interior has granted a visa allowing Breyten Breytenbach to come back to the land of his birth to visit his ailing parents. A compassionate visa, it is called; it covers both Breytenbach and his wife.

Breytenbach left the country years ago to live in Paris, and soon thereafter queered his pitch by marrying a Vietnamese woman, that is to say, a non-white, an Asiatic. He not only married her but, if one is to believe the poems in which she figures, is passionately in love with her. Despite which, says the Sunday Times, the minister in his compassion will permit the couple a thirty-day visit during which the so-called Mrs. Breytenbach will be treated as a white person, a temporary white, an honorary white.

Advertisement

From the moment they arrive in South Africa Breyten and Yolande, he swarthily handsome, she delicately beautiful, are dogged by the press. Zoom lenses capture every intimate moment as they picnic with friends or paddle in a mountain stream.

The Breytenbachs make a public appearance at a literary conference in Cape Town. The hall is packed to the rafters with people come to gape. In his speech Breyten calls Afrikaners a bastard people. It is because they are bastards and ashamed of their bastardy, he says, that they have concocted their cloud-cuckoo scheme of forced separation of the races.

His speech is greeted with huge applause. Soon thereafter he and Yolande fly home to Paris, and the Sunday newspapers return to their menu of naughty nymphets, errant spouses, and state murders.

To be explored: the envy felt by white South Africans (men) for Breytenbach, for his freedom to roam the world and for his unlimited access to a beautiful, exotic sex-companion.

2 September 1973

At the Empire Cinema in Muizenberg last night, an early film of Kurosawa’s, To Live. A stodgy bureaucrat learns that he has cancer and has only months to live. He is stunned, does not know what to do with himself, where to turn.

He takes his secretary, a bubbly but mindless young woman, out to tea. When she tries to leave he holds her back, gripping her arm. “I want to be like you!” he says. “But I don’t know how!” She is repelled by the nakedness of his appeal.

Question: How would he react if his father were to grip his arm like that?

13 September 1973

From an employment bureau where he has left his particulars he receives a call. A client seeks expert advice on language matters, will pay by the hour—is he interested? Language matters of what nature, he inquires? The bureau is unable to say.

He calls the number provided, makes an appointment to go to an address in Sea Point. His client is a woman in her sixties, a widow whose husband has departed this world leaving the bulk of his considerable estate in a trust controlled by his brother. Outraged, the widow has resolved to challenge the will. But both firms of lawyers she has consulted have counseled her against trying. The will is, they say, watertight. Nevertheless she refuses to give up. The lawyers, she is convinced, have misread the wording of the will. Giving up on lawyers, she is instead seeking expert support of a linguistic kind.

With a cup of tea at his elbow he peruses the will. Its meaning is perfectly plain. To the widow goes the flat in Sea Point and a sum of money. The remainder of the estate goes into a trust for the benefit of his children by a former marriage.

“I fear I cannot help you,” he says. “The wording is unambiguous. There is only one way in which it can be read.”

“What about here?” she says. She leans over his shoulder and stabs a finger at the text. Her hand is tiny, her skin mottled; on the third finger is a diamond in an extravagant setting. “Where it says Notwithstanding the aforesaid.”

“It says that if you can demonstrate financial distress you are entitled to apply to the trust for support.”

“What about notwithstanding ?”

“It means that what is stated in this clause is an exception to what has been stated before and takes precedence over it.”

“But it also means that the trust cannot withstand my claim. What does withstand mean if it doesn’t mean that?”

“It is not a question of what withstand means. It is a question of what Notwithstanding the aforesaid means. You must take the phrase as a whole.”

She gives an impatient snort. “I am hiring you as an expert on English, not as a lawyer,” she says. “The will is written in English, in English words. What do the words mean? What does notwithstanding mean?”

A madwoman, he thinks. How am I going to get out of this? But of course she is not mad. She is simply in the grip of rage and greed: rage against the husband who has slipped her grasp, greed for his money.

“The way I understand the clause,” she says, “if I make a claim then no one, including my brother-in-law, can withstand it. Because that is what not withstand means: he can’t withstand me. Otherwise what is the point of using the word? Do you see what I mean?”

“I see what you mean,” he says.

He leaves the house with a check for ten rands in his pocket. Once he has delivered his report, his expert report, to which he will have attached a copy, attested by a commissioner of oaths, of the degree certificate that makes him an expert commentator on the meaning of English words, including the word notwithstanding, he will receive the remaining thirty rands of his fee.

He delivers no report. He forgoes the money that is owed him. When the widow telephones to ask what is up, he quietly puts down the receiver.

Features of his character that emerge from the story: (a) integrity (he declines to read the will as she wants him to); (b) naiveté (he misses a chance to make some money).

31 May 1975

South Africa is not formally in a state of war, but it might as well be. As resistance has grown, the rule of law has step by step been suspended. The police and the people who run the police (as hunters run packs of dogs) are by now more or less unconstrained. In the guise of news, radio and television relay the official lies. Yet over the whole sorry, murderous show there hangs an air of staleness. The old rallying cries— Uphold white Christian civilization! Honor the sacrifices of the forefathers!—lack all force. We, or they, or we and they both, have moved into the endgame, and everyone knows it.

Yet while the chess players maneuver for advantage, human lives are still being consumed—consumed and shat out. As it is the fate of some generations to be destroyed by war, so it seems the fate of the present one to be ground down by politics.

If Jesus had stooped to play politics he might have become a key man in Roman Judea, a big operator. It was because he was indifferent to politics, and made his indifference clear, that he was liquidated. How to live one’s life outside politics, and one’s death too: that was the example he set for his followers.

Odd to find himself contemplating Jesus as a guide. But where should he search for a better one?

Caution: Avoid pushing his interest in Jesus too far and turning this into a conversion narrative.

2 June 1975

The house across the street has new owners, a couple of more or less his own age with young children and a BMW. He pays no attention to them until one day there is a knock at the door. “Hello, I’m David Truscott, your new neighbor. I’ve locked myself out. Could I use your telephone?” And then, as an afterthought: “Don’t I know you?”

Recognition dawns. They do indeed know each other. In 1952 David Truscott and he were in the same class, Standard Six, at St. Joseph’s College. He and David Truscott might have progressed side by side through the rest of high school but for the fact that David failed Standard Six and had to be kept behind. It was not hard to see why he failed: in Standard Six came algebra, and about algebra David could not grasp the first thing, the first thing being that x, y, and z were there to liberate one from the tedium of arithmetic. In Latin too, David never quite got the hang of things—of the subjunctive, for example. Even at so early an age it seemed to him clear that David would be better off out of school, away from Latin and algebra, in the real world, counting banknotes in a bank or selling shoes.

But despite being regularly flogged for not grasping things—floggings that he accepted philosophically, though now and again his glasses would cloud with tears—David Truscott persisted in his schooling, pushed no doubt from behind by his parents. Somehow or other he struggled through Standard Six and then Standard Seven and so on to Standard Ten; and now here he is, twenty years later, neat and bright and prosperous and, it emerges, so preoccupied with matters of business that when he set off for the office in the morning he forgot his house key and—since his wife has taken the children to a party—can’t get into the family home.

“And what is your line of business?” he inquires of David, more than curious.

“Marketing. I’m with the Woolworths Group. How about you?”

“Oh, I’m in between. I used to teach at a university in the United States, now I’m looking for a position here.”

“Well, we must get together. You must come over for a drink, exchange notes. Do you have children?”

“I am a child. I mean, I live with my father. My father is getting on in years. He needs looking after. But come in. The telephone is over there.”

So David Truscott, who did not understand x and y, is a flourishing marketer or marketeer, while he, who had no trouble understanding x and y and much else besides, is an unemployed intellectual. What does that suggest about the workings of the world? What it seems most obviously to suggest is that the path that leads through Latin and algebra is not the path to material success. But it may suggest much more: that understanding things is a waste of time; that if you want to succeed in the world and have a happy family and a nice home and a BMW you should not try to understand things but just add up the numbers or press the buttons or do whatever else it is that marketers are so richly rewarded for doing.

In the event, David Truscott and he do not get together to have the promised drink and exchange the promised notes. If of an evening it happens that he is in the front garden raking leaves at the time when David Truscott returns from work, the two of them give a neighborly wave or nod across the street, but no more than that. He sees somewhat more of Mrs. Truscott, a pale little creature forever chivvying children into or out of the second car; but he is not introduced to her and has no occasion to speak to her. Tokai Road is a busy thoroughfare, dangerous for children. There is no good rea- son for the Truscotts to cross to his side, or for him to cross to theirs.

3 June 1975

From where he and the Truscotts live one has only to stroll a kilometer in a southerly direction to come face to face with Pollsmoor. Pollsmoor—no one bothers to call it Pollsmoor Prison—is a place of incarceration ringed around with high walls and barbed wire and watch towers. Once upon a time it stood all alone in a waste of sandy scrubland. But over the years, first hesitantly, then more confidently, the suburban developments have crept closer, until now, hemmed in by neat rows of homes from which model citizens emerge each morning to play their part in the national economy, it is Pollsmoor that has become the anomaly in the landscape.

It is of course an irony that the South African gulag should protrude so obscenely into white suburbia, that the same air that he and the Truscotts breathe should have passed through the lungs of miscreants and criminals. But to the barbarians, as Zbigniew Herbert has pointed out, irony is simply like salt: you crunch it between your teeth and enjoy a momentary savor; when the savor is gone, the brute facts are still there. What does one do with the brute fact of Pollsmoor once the irony is used up?

Continuation: the Prisons Service vans that pass along Tokai Road on their way from the courts; flashes of faces, fingers gripping the grated windows; what stories the Truscotts tell their children to explain those hands and faces, some defiant, some forlorn.

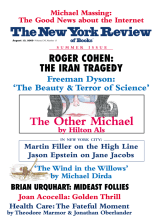

This Issue

August 13, 2009

When Science & Poetry Were Friends

A Very Chilly Victory