Barack Obama has long emphasized the importance of reforming American medical care, both as a candidate in the 2008 election and as president. During the month of June, however, he dramatically increased his efforts to secure major reform legislation by the end of the year.

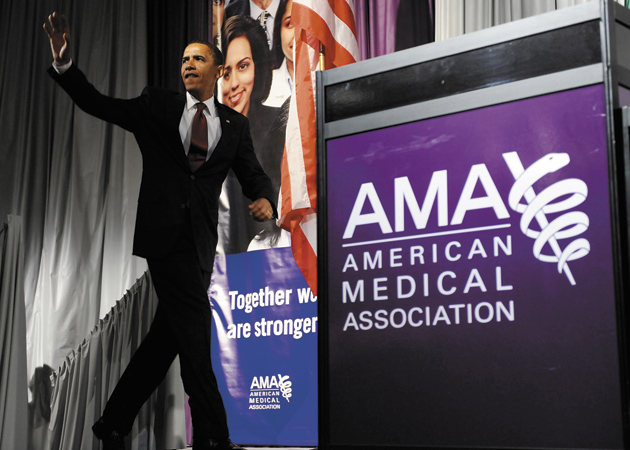

The President is using his oratorical skills to rally support for reform. In a series of speeches and town hall meetings, Obama made his case for expanding insurance coverage and controlling medical spending. Speaking before the annual meeting of the American Medical Association in Chicago on June 15, for example, he painted a familiar, distressing portrait of a health care system that costs too much, leaves too many Americans without adequate insurance, and too often provides substandard care. The President warned of the dire consequences if these problems were not promptly addressed:

Make no mistake: the cost of our health care is a threat to our economy. It’s an escalating burden on our families and businesses. It’s a ticking time-bomb for the federal budget. And it is unsustainable for the United States of America.

Yet as the President expands his involvement in the health care debate, health reformers have concluded that time is not on their side. Delay and the President’s popularity might well ebb. Congress could become more cautious as the 2010 elections approach. The longer the health care debate drags on, the more time opponents have to mobilize against and foster public anxiety about reform. And with federal budget deficits soaring, the political opportunities to finance expanded health insurance coverage may fade.

Democrats have consequently sped up congressional debate on how to change health care. By July, committees in both the House of Representatives and Senate were writing and amending ambitious legislation. The goal was to pass bills in both the House and Senate by the August recess. A conference committee will then have to reconcile the differing bills, though President Obama has said that he wants Congress to have legislation ready for him to sign by October 15.

1.

The fear that a promising start to reform could unravel arises from past experience. That, after all, is precisely what happened to the Clinton administration. In 1993, as in 2009, the US appeared to be on the verge of enacting comprehensive health reform. Then, as now, a Democratic president came to the White House with sizable Democratic majorities in the House and Senate. With increasing costs and growing numbers of uninsured, the administration believed it had a public mandate for reform. There was consensus on the need for change from a variety of interest groups, including businesses threatened by rising health insurance bills. Clinton’s plan proposed both to achieve universal coverage and to control costs by requiring employers to pay for their workers’ health insurance, establishing a system of regulated competition between private insurers, and setting limits on increases in health insurance premiums.

Despite seemingly favorable conditions, the Clinton administration’s campaign for health reform ended disastrously for Democrats. Its Health Security Act never came close to passing Congress and in the 1994 elections the party lost majorities in both the House and Senate. It is little wonder, then, that in 2009 the Obama administration and congressional Democrats have tried, above all else, to learn from the Clinton debacle.

In that respect, Tom Daschle’s book Critical: What We Can Do About the Health-Care Crisis offers an unusually helpful primer on the Obama administration’s approach to health reform. Before a controversy over Daschle’s tax problems led the former senator to withdraw his candidacy, he was President Obama’s nominee for secretary of health and human services (HHS) and choice as the White House’s health care “czar.” One of Daschle’s coauthors, Jeanne Lambrew, is now in the Obama administration as director of HHS’s Office of Health Reform. Moreover, Daschle’s views about how to pass health reform—including the imperative of a new president acting immediately—are clearly evident in the administration’s strategy.

According to Daschle, Clinton’s reform failed largely because of timing. Protracted battles over the administration’s other policy proposals, as well as crises abroad, delayed action on health care, eroded Clinton’s popularity, and gave the opposition time to coalesce. Powerful industry groups—including the Health Insurance Association of America and the National Federation of Independent Business—fought intensely against the Health Security Act. The Clinton administration, Daschle writes, ignored congressional leaders and excluded health industry groups from the planning process, which “bred resentment.” Finally, the Clinton approach to reform—emphasizing the transformation of private health insurance—took too little account of the political reality that “many people who have insurance now are satisfied with it, and are wary of changes.”

Advertisement

Daschle’s proposed health reform, aimed at achieving universal coverage, emerges from this reading of history. As one major step, he wants to expand existing public programs, including Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program.1 He also favors a national insurance pool in which Americans could choose from among private plans or from a new public plan modeled on Medicare. In such a pool, private plans would be barred from discriminating against sicker persons, whether by refusal of coverage or higher premiums. Employers would have to provide workers with insurance coverage or pay a tax to finance the insurance pool. Individuals would be “mandated”—required by law—to obtain insurance coverage or pay a penalty. This is not, Daschle emphasizes, a “pure model” that relies exclusively on the government as a “single payer.” Rather, it is a “hybrid solution” that maintains both public and private insurance, making it, according to Daschle, “politically and practically feasible.”

2.

If Daschle’s strategic and substantive prescriptions seem familiar, that is because the Obama administration and congressional Democrats are essentially following the recommendations of Critical. Despite urgent policy matters on many fronts, the Obama administration has decided, as Chief of Staff Rahm Emmanuel put it, to “throw long” and push for bold health reform this year, capitalizing on Barack Obama’s popularity and on an economic crisis that has given additional support for federal activism. Mindful of the difficulties in securing a sixty-vote, filibuster-proof majority in the Senate, the Obama administration successfully pressed Congress to create an alternative path to reform by adopting reconciliation rules (which the Clinton administration was unable to do). Under those rules, if Congress does not act by October 15, the Senate could pass health care legislation with a simple majority of fifty-one votes.

Other lessons from the Clinton debacle are evident in the White House’s strategy. Obama left primary responsibility for drafting the health reform plan to Congress. Though the President has articulated broad principles he would like to be followed—including adopting some kind of public insurance option and reducing overall costs—he has indicated that he is flexible about how Congress translates those principles into legislation. Wary of how the Clinton health plan frightened middle-class insured Americans, the Obama administration has emphasized that Americans who are satisfied with their present coverage and doctors can keep them.

Taking another lesson from 1993–1994, Obama and Senate leaders have sought to avoid a multifront war with the health care industry and business community by including both in discussions about reform. That has meant negotiating pledges by industry groups to back reform provisions (a promise by drug companies to offer discounted medications to some Medicare beneficiaries is one example).

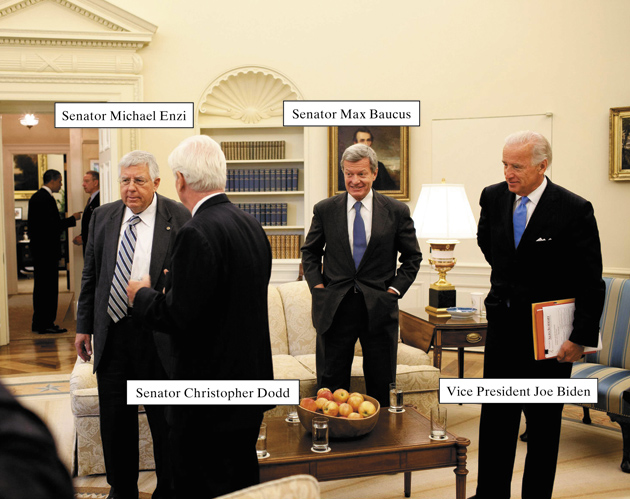

The Obama administration’s strategy of moving quickly, co-opting potential opposition, and deferring to Congress has mostly worked. In the first half of 2009, health reform legislation moved further and faster than many anticipated. The administration benefited from the determination of Democratic leaders, such as Senate Finance Chair Max Baucus, to pass ambitious legislation this year, as well as the Democrats’ relative unity—as compared to 1993–1994—on how to proceed. There is, in fact, broad agreement among congressional Democrats on a series of measures to expand insurance coverage. Those include (1) making more Americans eligible for Medicaid; (2) providing tax credits to Americans with modest incomes to help them afford insurance; (3) establishing a health insurance exchange that offers a range of coverage options; (4) regulating private insurers so they can’t turn anyone away, while also limiting their ability to charge sicker and older customers higher premiums; and (5) requiring individuals to obtain health insurance or pay a penalty, though persons for whom coverage was deemed unaffordable would be exempt from this mandate.

These measures, common to the various health reform bills now before the House and Senate, reflect what Obama proposed during the 2008 presidential election, with one notable exception. As a candidate, Obama criticized an individual mandate, but as president he has stated that he could support such a requirement if there were an exemption for financial hardship.

3.

The main outlines of health reform legislation that could become law this year are thus already visible. Yet as Congress drafts legislation, a number of difficult issues, from how to pay for reform and control costs to the inclusion of a public insurance option, will have to be resolved. There are profound divisions among Democrats in Congress over how such questions should be addressed and how necessary it is to attract Republican support. The fate of Obama’s health reform effort depends largely on how the administration and congressional leaders cope with these difficulties.

In the Senate, the two committees with primary jurisdiction in health care—the Finance Committee and the Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) Committee—are preparing separate bills that are to be merged into a single bill. The HELP Committee, chaired by Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy, is the more liberal of the two. In June and early July, HELP drafted legislation, with Connecticut Senator Chris Dodd overseeing the proceedings in the absence of Kennedy, who has brain cancer. These hearings were marked by sharp partisanship, with John McCain deriding the committee’s legislative process as “a joke.”

Advertisement

In mid-June, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that a preliminary version of the Kennedy plan would cost $1 trillion between 2010 and 2019, raising criticisms that it was too expensive. Dodd, however, was not concerned with Republican opposition: “My goal here,” he asserted, “is to write a good bill…not bipartisanship.” On July 2, the CBO estimated that the HELP Committee’s full bill would cost about $600 billion over ten years, though that estimate does not include the costs of a planned Medicaid expansion. On July 15, the committee approved the bill in a party-line vote.

In contrast, Max Baucus, the Montana Democrat chairing the Senate Finance committee, has been working on a bill intended to draw support from a small group of Republican Senators, including Iowa’s Chuck Grassley, as well as Democrats. Trying to secure Republican votes, Baucus has committed to keep the legislation’s cost to no more than $1 trillion over a decade.

In the House, on July 14, Representatives Charles Rangel, Henry Waxman, and George Miller—the Democratic chairs, respectively, of the Ways and Means, Energy and Commerce, and Education and Labor committees—jointly introduced a health reform plan known as the Tri-Committee Bill, which reflects the preferences of House liberals. It includes provisions that establish a Medicare-like public option for Americans under age sixty-five, and subsidies for low- and middle-income Americans to purchase insurance that extend to 400 percent of the federal poverty level ($43,000 for an individual, $88,000 for a family of four). It also requires that employers either provide health insurance coverage to their workers or pay up to an 8 percent payroll tax to the federal government.2 Smaller businesses with payrolls under $250,000 would be exempt from that tax.

Of the three bills, the Senate Finance Committee bill, which was expected to be announced in late July, will almost certainly be less liberal than either the House or HELP proposals. It is thus less likely to have generous subsidies for purchasing insurance or a meaningful public plan.

4.

The question of a public plan has emerged as the most contentious issue in health reform. What counts as a public plan option and whether it should be included at all in reform legislation divides most Democrats from nearly all Republicans, as well as conservative from liberal Democrats.3 The greatest difference between liberal Democratic plans and more conservative versions is whether the plan is an effective instrument of cost control. In a letter to Senators Baucus and Kennedy on June 2, President Obama wrote that he “strongly believe[s] that Americans should have the choice of a public health insurance option operating alongside private plans.” One crucial rationale for a new public plan along the lines of Medicare is that it would provide an alternative to for-profit private insurers who have long shunned sicker, higher-risk Americans. Even if reform legislation introduces regulations to prevent such discrimination, there is no guarantee that the insurance industry will reliably abide by them.

The strongest case for a public plan that will protect Americans from insurance industry abuses has been made, ironically, by the industry itself. In congressional testimony on June 16, insurance industry executives from WellPoint, UnitedHealth Group, and Assurant refused to end a controversial practice known as “rescission.” Under rescission, insurers retroactively cancel—often on the basis of dubious claims that policyholders haven’t disclosed their complete health histories—the coverage of those who develop expensive medical conditions. That has left many people with costly medical bills for treatments that had been previously authorized by their insurance. As Lisa Girion reported in the Los Angeles Times, the three insurers that were included in the June 16 hearing “canceled the coverage of more than 20,000 people, allowing the companies to avoid paying more than $300 million in medical claims over a five-year period.” In doing so they sought to avoid paying for the treatment of “policyholders with breast cancer, lymphoma and more than 1,000 other conditions.”4

There is no stronger indictment of American private insurers or better example of the profit motive’s corrosive influence on medicine than rescission. That insurers, even with political pressure for reform, would not forswear this practice in public hearings is stunning. It also illustrates how difficult a task it will be to transform the business practices of an industry that profits from discriminating against sick people.

Although there are good reasons to want a public plan that will not engage in such behavior, the risks should also be clear. It is quite possible that such a public plan would attract higher-risk enrollees, driving up its costs and sapping its political support. In theory, this problem could be solved by a federal insurance system that would pay more to insurers who enroll sicker populations. But in practice, effectively carrying out such risk adjustment is difficult.5

A second rationale for establishing a public plan is that it could effectively control its health spending. Like Medicare, a new federal health insurance program for Americans under sixty-five has the capacity—with its purchasing power—to restrain the prices it pays to hospitals, doctors, and other medical providers. Such a public plan, which would not need to make profits, almost surely would have lower administrative costs than private plans—for example, the traditional Medicare program devotes only 2 percent of its expenditures to administration, as compared to 11 percent for private Medicare Advantage plans. The potential for savings is significant. The United States has the most expensive health care in the world largely because we pay higher medical prices and incur higher administrative costs than other nations. (Greater use of some expensive medical technologies is another source of higher spending.)6 Offering lower premiums than private insurers, according to its backers, is a central advantage of a Medicare-like public plan.

That advantage explains why the insurance industry is trying to kill a public plan.7 Insurers argue that they would face an “un-level playing field” in competing against any public program, since the federal government would inevitably favor its own plan. Yet Medicare’s experience with such competition suggests that there is nothing inevitable about that alleged bias. The government now pays private insurers who enroll Medicare patients significantly more than it costs to treat them, enabling private plans both to offer better benefits than the traditional Medicare program and to make a profit.8

The insurance industry is, in fact, not interested in anything like a “level playing field.” Buffeted by the erosion of employer-sponsored insurance, the industry now welcomes the prospect of health reform that extends private insurance to the uninsured. But insurance firms do not want to lose new or existing customers (and profits) to a public competitor. New York Senator Chuck Schumer had proposed rules that circumscribe a public plan in order to ensure fair competition with private insurance. Schumer’s public plan would not be administered by the same officials who run the planned new insurance exchange; it would be financed only from beneficiary premiums and co-payments; and it would make a concession to the medical industry by paying higher rates to hospitals and doctors than Medicare currently does. Those stipulations have predictably not softened the insurance industry’s opposition. The American Medical Association, fearing the impact on physician incomes, also opposes both a strong public option and one such as Schumer’s.9

Financial motives, though, explain only part of the resistance to a robust public plan. Democratic Party leaders had hoped that their hybrid model of health reform—with both public and private insurance—would avoid the familiar ideological charges that helped doom past campaigns for national health insurance. That hope has been dashed—yesterday’s struggles over “socialized medicine” have become today’s debate over a “government takeover” of American medicine. The mistake is to believe that creation of any new public insurance program, even if only an option and not a single plan for the whole country, can escape such controversy. Scare talk about big government and threats to free enterprise is always present in debates about providing, financing, and regulating American health insurance. In words that echo health care debates of the twentieth century, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell recently warned of the dangers of a “government-run…system in which care is denied, delayed, and rationed.”

As McConnell’s statement suggests, nearly all Republicans fiercely oppose a public plan as an unwarranted expansion of the federal government. Conservative Democrats like Nebraska Senator Ben Nelson are similarly wary of a public insurance option. In the House, liberals are numerous enough that the Tri-Committee’s Medicare-like public plan could pass without any Republican votes—if the leadership can convince some conservative, “Blue Dog” Democrats to go along.

The place of any public plan in Senate legislation is far less certain, even though a recent national survey found that 72 percent of those questioned favored a government plan like Medicare for those under sixty-five. Max Baucus’s commitment to a bipartisan bill that a few Republicans and conservative Democrats can support means that the Senate Finance Committee has effectively jettisoned a meaningful public plan. Instead, there is an evolving search to find a politically acceptable stand-in.

One alternative under consideration is a trigger mechanism whereby the public plan would come into existence only if health reform did not meet specified goals. Another is North Dakota Democrat Kent Conrad’s proposal for a network of nonprofit health care “co-ops” that would be governed by consumers in local or regional insurance markets. But very few health care co-ops currently exist and if they are to be a centerpiece of reform it is not at all clear how they would work. This idea, which requires building health insurance plans from scratch, has nonetheless attracted some support in the Senate. That development represents a triumph of political and ideological accommodation over prudent policy.

The question of who would be eligible to enroll in a public plan is itself controversial. Congress is proposing tight limits on who would be able to choose a public plan. (For example, people without health insurance would be among those eligible.) Consequently, enrollment could be smaller than critics fear and advocates desire. According to a preliminary estimate by the Congressional Budget Office, by 2019, under the House plan, only 30 million Americans would participate in the new national insurance pool including both public and private plans; and of those, only 9 to 10 million—about 3 percent of the population—would enroll in the public plan. With such modest enrollment, the public plan would have minimal effect on reducing medical care spending.

5.

The controversy over a strong, Medicare-like public plan in the current debate is consequential because most of the instruments for cost control under consideration in Congress are strikingly weak.10 None of the House and Senate bills has any system-wide limits on health spending akin to the budgets and spending targets that other nations employ to restrain health care costs.11 The administration and congressional Democrats have instead substituted a set of politically more appealing policies: paying hospitals and doctors on the basis of the quality of care provided, enhancing preventative medicine, promoting electronic medical records, investing in more research on the effectiveness of medical treatments, and improving the coordination of care for chronic diseases.

These measures have appeal largely because they emphasize goals that no one would challenge—a healthier population and higher-quality medical care. They seem like benign devices to moderate health spending. Although the Obama administration refers to such reforms as “game changers,” there is little evidence that they can effectively control costs.12 The starting point for understanding the realities of cost control is an axiom of medical economics: a dollar spent on medical care is a dollar of income to someone in the health care industry—insurers, hospitals, doctors, pharmaceutical companies, and others.13 Placing limits on such costs means less income for the medical industry, and that is always politically controversial.

The illusion of painless cost control confronts another serious problem. The Congressional Budget Office is skeptical that measures such as greater use of electronic medical records will substantially slow health care spending, and the CBO will not, therefore, treat them as sources of major budgetary savings. The Obama administration and Congress have been consequently forced into considering more painful options to finance expanded health insurance coverage.14 For example, the administration has proposed about $600 billion in savings by reducing federal spending on health care over the next decade—mostly by cutting Medicare payments to hospitals, health insurers, and other medical providers. Financing health reform largely from Medicare savings, however, does not dampen inflation in private health spending. This, in turn, exposes the sharp distinction between reducing the costs that governments bear and restraining overall medical expenditures.

Even if Congress approves the proposed cuts in Medicare, it will require more funds to finance reform legislation without increasing the federal deficit.15 There is no uncontroversial way to do this. The House has proposed an income tax surcharge on wealthy Americans, starting at 1 percent for married households making over $350,000 ($280,000 for individuals), going up to a maximum of 5.4 percent for those with incomes in excess of $1 million. The Senate Finance Committee had been set to tax high-priced, employer-sponsored insurance plans but opposition from labor unions and Senate Democratic leaders forced the committee to consider additional options, such as fees to be paid by pharmaceutical companies and health insurers. The Senate has not released, at this writing, its final financing plan. How Congress chooses to pay for health reform will be one of the crucial conflicts of the coming weeks.

6.

What kind of legislation can we realistically expect to be enacted in 2009? House Democrats have a good chance, as noted above, of winning passage for the Tri-Committee Bill. With Al Franken finally in the Senate, Democrats have a filibuster-proof majority that could pass health reform without any Republican votes (though that assumes all conservative Democrats would back a reform that does not have bipartisan support). As mentioned, the Senate could also use reconciliation rules, which require only a simple majority, to pass health care legislation. However, some Democratic senators are reluctant to invoke reconciliation rules for both political and technical reasons. Max Baucus, for his part, has insisted upon enacting reform on a bipartisan basis. Furthermore, the reconciliation process risks producing legislative “Swiss cheese,” since the Senate parliamentarian has the authority to exclude any provision he regards as irrelevant.16

If both houses of Congress pass health reform legislation, a conference committee will struggle with reconciling divergent bills and conflicting political coalitions. The political dilemma is that abandoning a strong public plan—in order to win votes from centrist Democrats and moderate Republicans in the Senate—will alienate liberal Democrats in the House, who threaten to withhold support if such a plan is not included.

President Obama’s involvement in this political endgame will be crucial. The most important unanswered question in health reform is how much influence the President will exert on the conference committee. Will Obama successfully pressure Senate conferees to accept a more liberal reform—including a robust public plan—than they prefer? Or will he accept a more conservative bill in order to take credit for a political victory?17

Whatever health reform legislation emerges this fall (if any), we can plausibly predict that it will substantially reduce the number of uninsured Americans. That in itself would be a major achievement, though it will surely fall short of universal coverage. Moreover, unless it provides system-wide limits on health care spending, any legislation that emerges from Congress will not reliably control the costs of medical care. These two issues are closely linked. Failure to control costs would jeopardize the very gains in health insurance coverage that reform promises.

—July 16, 2009

This Issue

August 13, 2009

When Science & Poetry Were Friends

A Very Chilly Victory

-

1

The creation of a Federal Health Board is a crucial component of Daschle’s reform plan. The health board draws on two institutional models, the Federal Reserve and the Base Realignment and Closure Commission. Both institutions are devices to restrict the scope of congressional policymaking in controversial issues, whether setting interest rates or closing military bases. A Federal Health Board would be comprised by “respected experts,” as Progressives in the early twentieth century recommended. The board would, Daschle envisions, “make the tough changes that have eluded Congress in the past,” including “ranking [medical] services and therapies by their health and cost impacts.” Yet the search for specialized and disinterested competence to supplant legislative influence in health policymaking, as the recent debate over federal funding for comparative effectiveness research illustrates, is certain to cause political controversy.

↩ -

2

The House Tri-Committee Bill also calls for establishing a “new independent Advisory Committee, with practicing providers and other health care experts” that would recommend what medical services a “basic benefits package” would include. This is a truncated version of the Daschle model of a Federal Health Board discussed in footnote 1.

↩ -

3

There is much confusion over what a public plan signifies. We use the phrase “Medicare-like public plan” to describe the strong version favored by liberal Democrats. The three common features of such a plan include (1) the federal government bears the financial risk of insurance; (2) the plan can use its purchasing power to restrain costs; and (3) the plan is national in the sense that coverage is available on common terms throughout the country. Weaker versions lack one or more of these features.

↩ -

4

Lisa Girion, “Health Insurers Refuse to Limit Rescission Insurance Coverage,” Los Angeles Times, June 17, 2009.

↩ -

5

See Paul Starr, “Perils of the Public Plan,” The American Prospect, June 29, 2009. For an example of international experience with the problem of risk selection by insurers, see Kieke G.H. Okma, “Recent Changes in Dutch Health Insurance: Individual Mandate or Social Insurance?,” in Expanding Access to Health Care, edited by Terry F. Buss and Paul N. Van de Water (M.E. Sharpe, 2009).

↩ -

6

McKinsey Global Institute, “Accounting for the Cost of Health Care in the United States,” January 2007; Gerard F. Anderson et al, “It’s the Prices, Stupid: Why the United States Is So Different from Other Countries,” Health Affairs, Vol. 22, No. 3 (May/June 2003).

↩ -

7

The physician and former governor Howard Dean, in his new book, Prescription for Real Healthcare Reform (Chelsea Green, 2009), similarly argues that “if the Medicare-like public option could use its efficiency to deliver high-quality, cost-effective care, it would attract more enrollees. After all, this is the crux of why conservatives and the private insurance industry so vigorously object to a public plan. Their real concern is sacrificing profits to competition.”

↩ -

8

The Obama administration has proposed cutting these excessive payments to private insurers offering Medicare Advantage plans.

↩ -

9

The irony is that, on the one hand, conservatives oppose the public plan because it will be so inexpensive it will drive out private insurance, while on the other hand, these same critics decry the inefficiency and unaffordability of government programs. For an example, see Karl Rove, “How to Stop Socialized Health Care,” TheWall Street Journal, June 11, 2009.

↩ -

10

See Arnold Relman, “The Health Reform We Need and Are Not Getting,” The New York Review, July 2, 2009.

↩ -

11

See Joseph White, Competing Solutions: American Health Care Proposals and International Experience (Brookings Institution, 1995).

↩ -

12

For a fuller discussion of the limited cost-control potential of prevention, electronic medical records, and other delivery system reforms, see Theodore Marmor, Jonathan Oberlander, and Joseph White, “The Obama Administration’s Options for Health Care Cost Control: Hope vs Reality,” Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol. 150, No. 7 (April 2009).

↩ -

13

For a fuller elaboration of the axiom about medical spending and its political implications, see Robert G, Evans, Strained Mercy: The Economics of Canadian Health Care (Butterworths, 1984) and Theodore R. Marmor, Political Analysis and American Medical Care (Cambridge University Press, 1983).

↩ -

14

See Jonathan Oberlander, “Picking the Right Poison: Options for Funding Health Care Reform,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 360, No. 20 (May 2009).

↩ -

15

President Obama and congressional leaders are committed to adopting health reform legislation that adheres to pay-as-you-go budgeting rules. That means such legislation must be fully paid for with tax increases and/or spending cuts to remain “budget neutral.”

↩ -

16

Under the Byrd rule, legislative provisions can be challenged, and ultimately removed from a reconciliation bill, by senators on the grounds that they are that are extraneous to federal spending or revenue decisions. The Senate parliamentarian ultimately determines whether legislative provisions are extraneous. See Rebecca Adams, “The Risks of Using Reconciliation for Health Care Legislation,” Congressional Quarterly, April 2009.

↩ -

17

On the Obama administration’s theory of legislating reform—”pass a bill, take what you can get, and fix it later”—see Michael Tomasky’s discussion in “The Unencumbered Man,” The New York Review, July 2, 2009. In late June, Sheryl Gay Stolberg, a White House reporter for The New York Times, wrote in a front-page article that the President “has invested so much capital in a health care bill that not to have legislation would be politically disastrous for him.” See “Obama Steers Health Debate Out of Capital,” The New York Times, June 30, 2009.

↩