To the Editors:

Charter 08, which was announced on December 9, 2008, and whose English translation was published in The New York Review [January 15], was a statement by Chinese citizens addressed to other Chinese citizens on matters of our common quest for human rights and democracy. I am a lawyer and one of the charter’s signers.

The day before the charter appeared, the poet and literary critic Dr. Liu Xiaobo, who was also a signer and one of the charter’s drafters, was detained by police and held indefinitely. Liu’s wife, Ms. Liu Xia, immediately approached me to request that my firm (called the Mo Shaoping Law Firm) represent Liu in his legal defense. I agreed. We drafted a legal complaint to present to the office that deals with political dissidents, which is something called the General Affairs Office of the Beijing Public Security Bureau. This office maintains a certain air of mystery about itself, so does not publish its address or other contact details, but Liu Xia and I knew where to find it. When we arrived an official there told us he knew nothing about the Liu Xiaobo matter. He refused to accept our papers.

This obliged us to turn to the main office of the Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau. An official there accepted our papers, but made it clear that he was only “receiving materials” and could make no representations about when a response might be forthcoming.

Our complaint made these two points:

• When police detained Liu Xiaobo on December 8, 2008, the document they left with Liu Xia left blank the item “suspected of the crime of _________.” To leave this blank is a violation of Chinese law.

• After the police took Liu Xiaobo away, they informed Liu Xia orally that her husband was being held under “residential surveillance.” According to Chinese law “residential surveillance” is to be done in the suspect’s own residence, and both family members and lawyers are to be able to meet with the suspect freely, with no need for approvals. But Liu Xiaobo was being held at a location unknown to his family and lawyers.

The police have never responded to this written complaint. They did allow Liu Xia two brief and strictly monitored visits with her husband, on January 1, 2009, and on March 20, 2009.

Chinese law states that six months is the maximum period during which a person can be held in “residential surveillance.” Accordingly, on June 8, 2009, we submitted another written complaint to the Beijing Public Security Bureau asking that it desist in its illegal detention of Liu Xiaobo. We also sent a letter to the Beijing Municipal Procuratorate [i.e., prosecutor’s office], which has responsibility for supervision of legal procedure, asking that office intervene to correct the illegal behavior of the Public Security Bureau. Neither office replied.

On June 23, 2009, the New China News Agency announced that Liu Xiaobo had been formally arrested and charged with “inciting subversion of state power.” It is a charge that can yield a sentence of up to fifteen years. The announcement, although not entirely unexpected, nevertheless shocked the community of China’s democracy and human rights defenders. For me and others at my law firm, it only added to our determination to do everything possible, within a very difficult legal environment, to seek Liu Xiaobo’s freedom.

Then a new problem arose. Police informed me that because I, like Liu, had signed Charter 08, I was ineligible to serve as Liu’s defense lawyer. This peculiar stipulation is devoid of any grounding in law. I asked the police to put it into writing, but they refused.

On June 25, after Liu Xia had received the official notice of her husband’s arrest, she and I and one of my junior colleagues went to the Beijing Public Security Bureau to initiate our defense of Liu Xiaobo. I began by trying to clarify my own right to serve as Liu’s lawyer. If signing Charter 08 disqualifies me from serving, does that mean, I asked, that signing Charter 08 is itself a crime? The official who met us did not answer directly. He said that since Liu’s case is still in the investigation stage, and has not yet been handed over to the Procuratorate, he could not give me a formal answer. I asked him which provision of Chinese law gives police the power to decide who can or cannot serve as a lawyer. To that, there was only silence. So I took it upon myself to inform him that, whether or not police presented barriers to my participation, I would be monitoring and assisting in the case at every stage.

On June 26, 2009, Liu Xia was permitted to meet with Liu Xiaobo. Police blocked me from attending, but two younger colleagues from my law firm did attend. They reported to me that the criminal investigators were focusing on two things: first, Charter 08; and second, various items of Liu Xiaobo’s writings between 2001 and the present. Liu Xiaobo had acknowledged his role in drafting Charter 08 and had allowed, as well, that he was indeed the author of the other works in question. But he denied that any of this activity constituted a crime, since all of it was exercise of a constitutional right to freedom of expression.

My own legal opinion is fully consistent with Liu’s. The ideas and values of Charter 08 are the same as those written into the United Nations Charter and the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The announcement of Charter 08 was timed to commemorate the Universal Declaration on its sixtieth anniversary. As a member of the United Nations, indeed its Security Council, China should have no problem accepting such ideals. Moreover the core values of Charter 08—freedom, democracy, equality—are universal values that are written into China’s constitution as well. To hold that the signing of Charter 08 is criminal behavior is preposterous.

The crime of “inciting subversion of state power,” as provided in clause no. 105 of China’s criminal law, is both flawed and vague. The Chinese constitution provides that citizens have the right of freedom of speech, so where exactly, one must ask, is the line between “freedom of speech” and “incitement to subversion”? China’s National People’s Congress has made no laws in this regard. Nor has either the Supreme People’s Court or the Supreme People’s Procuratorate offered any judicial interpretation of the question. In actual practice, the charge of “inciting subversion of state power” has been nothing but a convenient tool for use in suppression of political dissidents and human rights defenders. It has done serious harm to the right of free expression in China. If this kind of provision is to be maintained, our People’s Congress, Supreme Court, or Supreme Procuratorate must take steps to define it precisely and to strictly limit the possibilities of its abuse.

The Johannesburg Principles on National security, Freedom of Speech and Access to Information hold that punishment for expression must be strictly limited to cases in which expression can lead to present and immediate danger. None of Liu Xiaobo’s writings or his involvement with Charter 08 can remotely qualify as an infraction under such a criterion. The allegations against Liu Xiaobo of “incitement to subversion of state power” are obviously untenable.

If the past is a guide, what the Chinese authorities are now likely to do will be to comb through Liu Xiaobo’s many writings and then present some snippets as evidence of “incitement to subversion of state power.” Their broader motive will be to use the Liu Xiaobo case to try to frighten others into silence, or, as the Chinese proverb puts it, “to kill a chicken while the monkeys watch.” If they have their way, Liu will be converted from a champion of Charter 08 into an instrument of its repression.

But if this is how they are thinking, they would do well to note that the tide of history is against them. We will not be deterred from our continuing pursuit of freedom of expression.

Mo Shaoping

Mo Shaoping Law Firm

Beijing, China

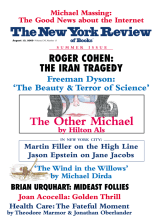

This Issue

August 13, 2009

When Science & Poetry Were Friends

A Very Chilly Victory