In response to:

The Universities in Trouble from the May 14, 2009 issue

To the Editors:

Andrew Delbanco effectively describes the tragedy that is unfolding at American universities: after a generation of expanding of opportunity, both private and public colleges are increasingly out of reach of the lower classes [“The Universities in Trouble,” NYR, May 14]. Unfortunately, Delbanco avoids the solution that is sitting right before him: free higher education. That’s the way most of the civilized world deals with the cost of higher education. And we have past and present examples in our own nation of providing free higher education—the GI Bill, CUNY, California’s community colleges, Georgia’s HOPE scholarships. My father went from immigrant to soldier to Ph.D. in the space of a decade, thanks to the GI Bill.

Would this be insanely expensive? The total cost of sending every single public university undergraduate to college for a year (that group makes up 75 percent of the total college enrollment) was $39.36 billion in 2006–2007. That’s not chicken feed, but it’s less than the bailout amount for two large banks, or the cost of three or four months in Iraq.

Public grade schools have been free since the nineteenth century; high schools were free when only a minority of our citizens attended. These days a college education is as necessary to success as a high school education was then. Just listen to what leaders at the opposite ends of the political spectrum say. Deval Patrick, governor of Massachusetts, former Clinton Justice Department official: “Success in a twenty-first-century global economy requires more than a high school diploma.” Margaret Spellings, Bush administration secretary of education: “What a high school diploma was in the 1950s is akin, more and more, to at least two years of postsecondary education today.” And now President Obama, in his speech to Congress: “Every American will need to get more than a high school diploma.”

It is time to make public higher education free.

Max Page

Associate Professor of Architecture and History

University of Massachusetts

Amherst, Massachusetts

Andrew Delbanco replies:

Mr. Page’s call for free college is an honorable ideal, but for reasons of both practice and principle, it is an implausible goal. For one thing, his estimate of cost is much too low. Even at prevailing college-going rates, according to The Chronicle of Higher Education, total state expenditures on public universities (for the academic year 2005–2006) were over $70 billion—an annual figure that does not include federal aid, scholarships dispensed by private institutions, and what students themselves are currently paying.

Apart from the question of whether taxpayers would be willing to bear such a high cost for universal free higher education (consider what is happening today in California, where public universities are reeling because of insufficient tax revenue), I wonder if it would it be fair to ask all taxpayers to support a benefit that would go disproportionately to those who are able to forgo full-time income in order to attend college. Even if college were “free”—free, that is, beyond the tax assessments needed to fund it—children with superior high school and test preparation would attend college at higher rates than those without such advantages. A system of free higher education would therefore amount to a regressive form of transfer payments from relatively low-income to higher-income families. Do we really want to cover the cost at public expense for all students at flagship state universities and elite private colleges, who tend to come from families of relatively high socioeconomic status?

Mr. Page points out that grade schools and high schools are free in this country; but it should be remembered that primary and (some) secondary schooling are mandatory, while college is not. As for the comparison to how “most of the civilized world” pays for college, college-going rates in Europe have historically been much lower than in the US. Now that this is changing, it is not clear whether free university education—along with other universal benefits such as state-financed childcare, medical care, and elder care—can be sustained.

Apart from these practical obstacles, there is also the question of whether we really want to abandon the principle that some personal investment in one’s own college education is a good thing—the principle by which families are asked to contribute an amount based on a fair calculation of their ability to pay, and students are expected to take on a reasonable amount of debt and/or to work at campus jobs.

Yes, college must be made more widely available in the US—but in order to do this in a fair and affordable way, the cost to students must be based on a rational calculation of need rather than provided at public expense without regard to the beneficiary’s financial means.

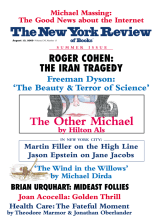

This Issue

August 13, 2009

When Science & Poetry Were Friends

A Very Chilly Victory