In his new book Terrorism: How to Respond,* Richard English, a historian who has written the definitive history of the IRA, argues that terrorism is best understood as a “subspecies of war” that embodies—among other things—“the exerting and implementing of power, and the attempted redressing of power relations.”

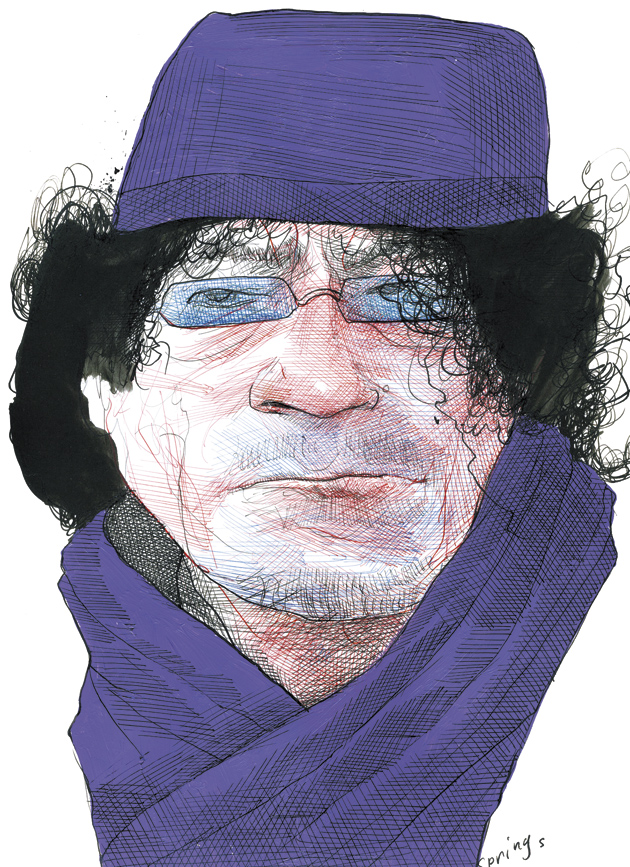

The furor over the Scottish government’s decision to release Abdel Basset Ali al-Megrahi, the convicted Lockerbie bomber, and the speculations surrounding the whole affair prove his point. The festive welcome Megrahi received from President Muammar Qaddafi himself on arrival in Libya was met with predictable fury on both sides of the Atlantic. The explosion aboard Pan Am Flight 103 on December 21, 1988, which caused the Boeing 747 to disintegrate in flames over the Scottish town of Lockerbie, was the worst terrorist atrocity ever to have been perpetrated on British soil. Two hundred and seventy people died, including eleven Lockerbie residents. The majority of the victims, 189 of them, were US citizens returning for the Christmas holidays.

President Obama’s spokesman, Robert Gibbs, described the jubilant crowds that greeted the frail figure of the returning Libyan intelligence agent as “outrageous and disgusting.” Robert Mueller, director of the FBI—who as assistant attorney general had been involved in the investigation that led to Megrahi’s indictment and conviction by a Scottish court sitting in the Netherlands—took the unusual step of releasing the text of a letter he had sent to the Scottish justice secretary, Kenny MacAskill, in which he complained that MacAskill’s action, “blithely defended on the grounds of ‘compassion,'” would give “comfort to terrorists around the world.”

The devolved Scottish government —under the Scottish National Party (SNP), which has announced its intention to hold a referendum on full independence—has robustly denied claims that business interests or pressures from the UK government had any part in its decision to release Megrahi. Its position was supported—after a lengthy and deafening silence—by British Prime Minister Gordon Brown, whom the opposition has accused of “double-dealing” over the Lockerbie affair:

I made it clear that for us there was never a linkage between any other issue and the Scottish government’s own decision about Megrahi’s future…. On our part there was no conspiracy, no cover-up, no double-dealing, no deal on oil, no attempt to instruct Scottish ministers, no private assurances by me to Colonel Qaddafi. We were absolutely clear throughout with Libya and everyone else that this was a decision for the Scottish government.

In an effort to support their position, the UK and Scottish governments released a pile of documents, including previously leaked correspondence between MacAskill and Jack Straw, his counterpart in London. The British justice secretary explained that in his dealings with the Libyan authorities he had been unable to persuade them to exclude Megrahi from a prisoner transfer agreement between Britain and Libya under which prisoners would serve their sentences in their respective countries. The documents also reveal that when the Libyan minister for Europe told his British counterpart that Megrahi’s death in a Scottish prison would have “catastrophic effects” on UK–Libyan relations, he was told that “neither the Prime Minister nor the Foreign Secretary would want Mr. Megrahi to pass away in prison but the decision on transfer lies in the hands of Scottish ministers.”

In fact the medical prognosis giving Megrahi less than three months to live provided both governments with a loophole in their dealings with Libya. Scottish prison service guidelines state that compassionate release “may be considered where a prisoner is suffering from a terminal illness and death is likely to occur soon,” with a life expectancy of around three months an “appropriate time” to consider release. Doctors had earlier concluded that Megrahi might have a year or more to live, rendering him ineligible for release in time for the celebrations marking the fortieth anniversary of the coup on September 1, 1969, that overthrew the Libyan monarchy and brought Qaddafi, a twenty-seven-year-old army captain, to power.

The three doctors—two British and one Libyan—who produced a revised prognosis in July were paid by the Libyan government. One of them, the British oncologist Professor Karol Sikora, medical director of CancerPartners UK, a private health care organization, admitted that the period of three months had been suggested by the Libyans. After examining Megrahi in prison and looking at the clinical details “in much greater depth” than previous doctors, Sikora concluded that Megrahi’s tumor “was behaving in a very aggressive way, unlike [tumors afflicting] most people with prostate cancer” and that “the three-month deadline seemed about right.” The Libyan doctor concurred. The third doctor would only say that Megrahi “had a short time to live.” After it became clear that Megrahi could not be excluded from the prisoner transfer agreement, it seems the Scottish and British governments actively encouraged him and his legal team to seek a release on compassionate grounds.

Advertisement

At stake, for the British, were contracts for oil and gas exploration worth up to £15 billion ($24 billion) for British Petroleum (BP), announced in May 2007, as well as plans to open a London office of the Libyan Investment Authority, a sovereign fund with £83 billion ($136 billion) to invest. Libya refused to ratify the contracts until Straw abandoned his insistence on excluding Megrahi from the prisoner transfer agreement. Shortly after Brown’s statement, Straw admitted—in apparent contradiction to his prime minister—that oil had been “a very big part” of his negotiations. British leaders were also warned that trade deals worth billions could be canceled. “The wider negotiations with the Libyans are reaching a critical stage,” Straw wrote to MacAskill in December 2007, “and in view of the overwhelming interests for the United Kingdom I have agreed that in this instance the PTA [prisoner transfer agreement] should be in the standard form and not mention any individual.” Within six weeks of the British government’s concession, Libya had ratified the BP deal. The prisoner transfer agreement was finalized in May of this year, leading to Libya formally applying for Megrahi to be transferred to its custody.

For the SNP government in Edinburgh, the “compassion loophole” made it possible to avoid authorizing Megrahi’s release under an agreement negotiated by London. The decision was widely condemned in Scotland, with the minority SNP administration losing a vote by 73–50 in the Scottish parliament on a government motion that the release of Megrahi on compassionate grounds was “consistent with the principles of Scottish justice.” But there was a further twist to this story. Before his release from Greenock prison near Glasgow and his flight to Tripoli in a chartered Libyan jet, Megrahi agreed to drop his appeal against the life sentence he received from the specially convened Scottish court sitting at Camp Zeist in the Netherlands in 2001.

Megrahi has always insisted on his innocence, and doubts about his conviction have been expressed by several influential figures, most notably Dr. Jim Swire, a spokesman for the UK families of Flight 103, whose daughter Flora died in the crash, and Professor Hans Köchler, official UN observer at Megrahi’s trial at Camp Zeist. In his reports to the UN secretary-general, Köchler deplored the political atmosphere of the trial and the failure of the court to consider evidence of foreign (i.e., non-Libyan) government involvement that formed part of a special defense—inculpating others—that is available under Scottish law.

He was even more forthright in condemning the rejection of Megrahi’s first appeal in March 2002—calling it a “spectacular miscarriage of justice”—which took place at the same time as discussions with Libya over compensation for the victims’ families. The presence of a Libyan “defense support team” hampered the efforts of the Scottish defense lawyers, who failed to raise vital questions about the withholding of evidence and the reliability of witnesses. Two notable omissions Köchler highlighted were the alleged coaching of a key prosecution witness by Scottish police and the appeal court’s failure to consider evidence of a break-in at the baggage storage area in London’s Heathrow airport on the night before the bombing.

Conspiracy theories have plagued the bombing ever since the clearing-up operation when unidentified Americans, thought to be CIA agents, were seen sorting through the debris alongside officially authorized Scottish police. The most plausible theories do not necessarily exonerate Megrahi, but do suggest that at most he was little more than a small cog in a much larger and more complex machine.

A widely held suspicion at the beginning of the investigation pointed toward the culpability of a Palestinian faction, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine–General Command (PFLP-GC), working under the protection of Syria. The theory held that the PFLP-GC, who specialized in aircraft hijackings using semtex bombs concealed in tape recorders, may have been “sub- contracted” by Syria’s Iranian allies to bring down Pan Am Flight 103 in revenge for the accidental shooting down of an Iranian civilian airliner by the USS Vincennes in July 1988, just months before the bombing of Flight 103.

At the time Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini vowed that the skies would “rain blood” in revenge for the loss of 290 civilian lives, including 66 children. Two defectors from Iranian intelligence agencies—or alleged defectors—subsequently accused the Iranian government of being behind the attacks for which the PFLP-GC was said to have been paid $10 million. Some analysts have argued that leads pointing toward the Palestinian-Syrian-Iranian connection were purposefully deflected after the 1990 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, when Syria became—albeit temporarily—a US coalition ally. Libya, the only Arab state to support Saddam’s invasion, remained a more tenable target for exacting exemplary justice.

Advertisement

After a decade of sanctions and interventions by UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan and South African President Nelson Mandela, the Libyans in 1999 gave up Megrahi and his alleged associate Lamin Khalifah Fhimah, who would later be acquitted. The case against Megrahi hinged on a fragment recovered at Lockerbie of a timing device traced to a Swiss manufacturer, Mebo. The firm had sold timers to Libya that differed in design from those allegedly used in cassette bombs of the type attributed to the PFLP-GC. The clothing in which the bomb was said to have been wrapped inside a suitcase was traced to a shop in Malta that Megrahi was alleged to have visited, traveling under an assumed name, on December 20–21, 1988.

Although the evidence was purely circumstantial (there was no direct evidence that either he or Fhimah had placed the device aboard the aircraft), the judges wrote in their decision that the preponderance of the evidence led them to believe that Megrahi was guilty as charged. He was sentenced to life imprisonment, with a recommended minimum of twenty-seven years, to be served in a Scottish jail. A major reason for US anger at Megrahi’s release has been the repeated assurances given by the British government that he would serve out his full term.

In December 2003, as part of its campaign to end UN sanctions and abandon its pariah status, Libya accepted responsibility for the bombing, and agreed to pay compensation to the victims’ families—although it continued to maintain Megrahi’s innocence, as he had done throughout his trial. His position divided observers: some see his continuing denial as the standard response of a professional intelligence officer, as summarized by the unofficial motto of the CIA’s Office of Technical Services—“admit nothing, deny everything, make counter-accusations.”

Others, including a significant group of Scottish lawyers and laypersons, take a different view. In June 2007, after an investigation lasting nearly four years, the Scottish Criminal Case Review Commission delivered an eight-hundred-page report—with thirteen annexes—that identified several areas where “a miscarriage of justice may have occurred” and referred Megrahi’s case to the Court of Criminal Appeal in Edinburgh. The commission considered evidence that cast doubt on the dates on which Megrahi was supposed to have been in Malta as well as the testimony of the Maltese shopkeeper who claimed to have sold clothing to Megrahi. He had changed his testimony several times, and had been shown Megrahi’s photograph before picking him out of a line-up. It was expected that the fresh appeal would also consider new evidence about the timing device, as well as the reported break-in at Heathrow airport, which indicate that the bomb could have been planted in London rather than in a suitcase checked from Malta to New York, as the prosecution had claimed.

In July 2007, Ulrich Lumpert, a former engineer at Mebo and a key technical witness, admitted that he had committed perjury at the Camp Zeist trial. In a sworn affidavit he declared that he had stolen a handmade sample of an MST-13 Timer PC-board from Mebo in Zurich and handed it to an unnamed official investigating the Lockerbie case. He also affirmed that the fragment of the timer presented in court as part of the Lockerbie wreckage had in fact been part of this stolen sample. When he became aware that this piece was to be used as evidence for an “intentionally politically motivated criminal undertaking,” he said, he decided to keep silent out of fear for his life.

Although it would have been necessary for Megrahi to drop his appeal under the prisoner transfer scheme, this was not a precondition for release on compassionate grounds. Nevertheless it seems likely that he was pressured into abandoning the appeal. Oliver Miles, a former British ambassador to Libya, has suggested that the dropping of the appeal, rather than “a deal involving business,” was the real quid pro quo behind Megrahi’s release. According to Miles, Scottish legal sources had been talking of a mood of “growing anxiety in the Scottish justice department that a successful appeal…would severely damage the reputation of the Scottish justice system.”

Although many British and American victims’ families are demanding a fuller inquiry, Megrahi’s decision means the end of any formal legal investigation into the Lockerbie atrocity. However, this is unlikely to be the end of the controversy, whatever the unpublicized hopes of the Scottish, UK, and US governments. Mark Zaid, the Washington lawyer who represents thirty American families and launched a lawsuit against the Libyan government, securing compensation of up to $2.7 billion, has announced that he is filing suit under the Freedom of Information Act to try to ascertain what agreements and discussions have taken place between the US and the UK, not just with respect to the release of Megrahi, but dating back to before the 1991 indictment. “It is ironic,” he told the BBC, “that in the latest release of documents from the British authorities the US viewpoint was redacted [i.e., parts of it were omitted] at the specific request of my government.”

In retrospect, the connection between the downing of the Iranian Airbus in July 1988 and of Pan Am Flight 103 five months later has never been adequately established, and probably never will be. In settlements ending hostilities, justice is often the victim.

— September 9, 2009

This Issue

October 8, 2009

-

*

Just published by Oxford University Press.

↩