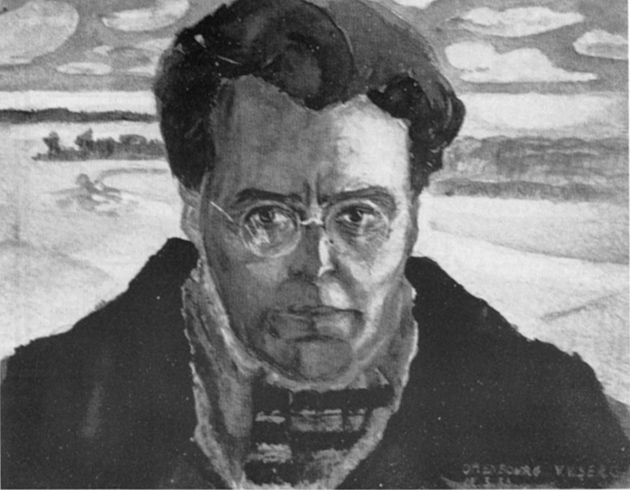

Singular and solitary, the novelist Victor Serge (1890–1947) appears as an orphan of history, a chance survivor improbably clinging to the coffin of the Bolshevik Revolution. The main characters of Unforgiving Years, Serge’s final novel, written in Mexico, the place of his own final exile, are his fictional brothers—disillusioned Soviet agents surviving the hell of wartime Europe only to be thrown, like he, into some hitherto unimagined Atlantic void.

Unforgiving Years begins with D, a dedicated revolutionary with a cyanide capsule adhered to his scalp who now believes himself hunted by Stalin’s agents. Looking for a way out of 1938 Paris, he contemplates his “final break with all the reasons for living—ideas, cause, motherland, unity in danger, invisible battle for the future, vision of a forward-marching world!” After D escapes to Mexico, his spiritual comrade Daria follows him on a westbound freighter, seven years and considerable suffering later. She’s “traveling on her last passport, her last money; outside every law, very possibly pursued, free, free!”—and naturally, for a Serge character in such circumstances, contemplating her extinction.

Creatures of thought as well as action, D and Daria are descendants of the talkative nineteenth-century Russian intelligentsia. Even (or perhaps especially) as the world falls apart, they are absorbed with the workings of their minds. “I’m turning into a character out of a novel for intellectuals,” D jokes to himself. During the siege of Leningrad, Daria hastens over blackened snow amid exploding shells, wondering if she is “still thinking within the material truth of history.” Stalin appears only as a poster in a government office; his name is never mentioned—nor are those of Lenin and Trotsky—but D and Daria spend considerable time pondering past associations, turning their service to the Party and Revolution over and over in their thoughts. During his last night on earth, D mentally revisits the Central Asian scene of a youthful exploit in the Russian civil war and poses the essential question: “How did we—insurgent, united, uplifted, and victorious—bring about the opposite of what we wanted to do?”

These characters may not speak for Serge but theirs are the voices that haunted him. D, the same age as Serge, muses that an entire historical epoch was required to shape him. Born in Brussels to revolutionary parents, brought up in one exile and dying in another, Serge passed his life in a succession of prisons and left-wing political parties. A participant in three European revolutions, he became familiar with millennial expectation and catastrophic loss. Only after he ceased to be a professional revolutionary did he become a novelist. His first book, Men in Prison, was set in France, written in German (and Germany), finished in Moscow, then mailed piecemeal back to France for publication. His best-known novel, The Case of Comrade Tulayev, was begun in Paris, then continued while he was on the run through France, crossed the Atlantic, and detained in the Dominican Republic. The book was finally completed in Mexico and published in France a year after the writer’s death. He was buried in Mexico City’s French cemetery, a “Spanish Republican.”

Victor Serge may not be a household name but neither is he completely unknown. His devastating analyses of Stalin’s Soviet Union were first translated by American Trotskyists in the late 1930s and were reprinted into the 1970s. Partisan Review published his essays and fiction. The Case of Comrade Tulayev was well received, if deemed by some critics inferior to Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon, when it appeared in English in 1950. In The Nation, Irving Howe called Serge’s novel “the best fictional portrait we have of Stalinist Russia, richly credible in atmospheric detail and bound by a coherent view of what Stalinism means.” (Writing in The New International, a sectarian Trotskyist publication, Howe was less detached, cautioning readers that “the material is so close to us, the point of view so congenial, the pathos so unbearable…that we are emotionally defenseless against the entire impact of the book.”) Despite his arguments with Trotsky, Serge was a Trotskyist hero. If he was largely forgotten by cold war liberals en route from youthful Trotskyism to mature neoconservatism, the British publication of Serge’s Memoirs of a Revolutionary, written in 1941 with the encouragement of Dwight Macdonald, stimulated his rediscovery by the New Left. Beginning in 1967, Richard Greeman translated and introduced Serge’s early novels, which at the same time had been reissued in France.1

The memoirs are crucial, for Serge’s greatest story was his life. His father, Lvov Kibalchich, was a noncommissioned officer of the Russian imperial guard with ties to the extremist revolutionary Narodniks who in 1881 assassinated Alexander II. (Indeed, his assignment was to shoot the Tsar should Alexander survive the first attempt on his life.) Serge’s parents escaped and took refuge in a Brussels slum. “On the walls of our humble and makeshift lodgings there were always the portraits of men who had been hanged,” their son would recall.

Advertisement

By age fifteen, Victor Kibalchich, as Serge was then known, had begun living on his own—as a photographer’s apprentice, a draftsman, and a linotype operator, organizing all the while for the Belgian Socialist Party. A few years later, having read Peter Kropotkin’s Appeal to the Young, he toured utopian colonies in Belgium and France. At nineteen, he moved to Paris and, working intermittently as a printer and translator, threw himself into the fringe political scene. Serge was a precursor of the New Left before he even joined the old one: he followed from the start anarchism’s most extreme line, asserting that not class warfare but the individual’s total revolt against the strictures of society would serve as the engine of social change. Calling himself Le Rétif (The Unbroken One), Serge wrote for L’anarchie and later, as the journal’s editor, went on to defend the violence of a few colorful motorcar-driving bank robbers known as the Bonnot Gang. The police searched L’anarchie ‘s offices and in 1911 found two revolvers; the fiery young editor was arrested, charged with harboring the bandits he had publicly defended, and imprisoned for five years (an experience he would describe in his first novel, Men in Prison).

Released in the midst of World War I, now calling himself Victor Serge, the twenty-seven-year-old anarchist made his way to neutral Barcelona to join up with the syndicalist organizer Salvador “Sugar Boy” Seguí. A rebellion broke out (and was crushed) but Serge was already en route to Russia; or rather, already on his way to a French prison camp where, although he then had no connection other than sentiment to the Russian Revolution, he would be detained for over a year as a Bolshevik agent. The uprising in Barcelona, the World War, and his abortive journey home provided material for Serge’s second novel, Birth of Our Power.

The Russian Revolution would be the supreme event of Serge’s life. He arrived in Red Petrograd, capital of the motherland he’d never seen, in early 1919; by May Day, he had become a functionary of the Communist Party. Serge criticized Lenin’s intolerance and his faith in the power of the state but he was also a realist—or so he thought at the time. “Within the current situation of Europe, bloodstained, devastated, and in profound stupor, Bolshevism was,” in his eyes, “tremendously and visibly right. It marked a new point of departure in history.”

Serge fought in defense of Petrograd, attacked twice that year by the White Army. He taught political education courses, working under Grigory Zinoviev, chairman of the Petrograd Soviet. Setting up the Com- intern publishing house and running its Romance-language section, editing international journals and cataloguing the archives of the tsarist secret police, Serge knew everyone—he moved in Petrograd’s ruling circles, while keeping in touch with Mensheviks, Left Social-Revolutionaries, and members of the so-called Workers’ Opposition. (He was the lone Bolshevik to attend the funeral of Kropotkin, the anarchist-Communist whose books had sent him off in search of Utopia as a teenager.)

The Bolsheviks’ massacre of thousands of sailors following the 1921 Kronstadt Rebellion shook Serge’s faith. Requesting to be sent on a mission to the West, he was dispatched to Berlin to edit the Comintern’s European press service—and also to serve as an agent of the German Communist Party. Spirited out of Berlin with the failure of the Communists’ 1923 Hamburg putsch, Serge returned to the Soviet Union in 1926. Two years later, having written an imprudent article that described the recent expulsion of Trotsky and the oppositionists as a “grave error,” Serge was himself expelled from the Party and shortly thereafter arrested by the secret police for “anti-Soviet activity.” He nearly died of an intestinal occlusion twenty-four hours after leaving prison. It was then, approaching forty, that Serge resolved to become an artist, mentally sketching a series of documentary novels about what he had seen and experienced—the extreme circumstances of prison, revolution, and political persecution.

Over the next few years, Serge completed Men in Prison and two other novels, Birth of Our Power and Conquered City (a nightmarish account of Red terror), as well as a history, Year One of the Russian Revolution—all composed in fragments and mailed to friends in Paris so that if their author was again arrested (as he eventually would be), the assembled manuscripts could be published abroad (as they were). In their tone, the novels have the immediacy of battlefield reports. The nameless narrators of Men in Prison and Birth of Our Power, and even that of the more personal Memoirs of a Revolutionary—itself a series of snapshot portraits—are observers. Apparently blessed with total recall, Serge excelled at character vignettes; his books are remarkable for their swarming casts. Notwithstanding a talent for describing different personalities, he took seriously the notion of a collective hero, writing in his memoirs:

Advertisement

Individual existences were of no interest to me—particularly my own—except by virtue of the great ensemble of life whose particles, more or less endowed with consciousness, are all that we ever are.

In early 1933, Serge was deported to a prison camp in Orenburg, on the border of Kazakhstan (the setting for his later novel Midnight in the Century). But by now he was a known figure in Paris. Intellectuals rallied to his cause; he was released in the spring of 1936 (a favor Stalin granted the French fellow traveler Romain Rolland) and expelled from the Soviet Union. Two complete novels—one an account of the pre-war French anarchists, the other a sequel to Conquered City—as well as a book of poetry and the continuation of his history, Year Two of the Russian Revolution, were confiscated by the secret police before he left. The Spanish civil war broke out shortly after he arrived back in the West. Weeks later, Stalin charged his old Bolshevik comrades with treason. That summer, the first major show trial opened, with Serge’s erstwhile boss Grigory Zinoviev, an early Bolshevik and former supporter of Trotsky, accused along with fifteen coconspirators of the murder of Sergei Kirov and planning the death of Stalin, among other crimes.

Serge’s remaining family members in the Soviet Union began to vanish; in Paris, he set up a Committee for Inquiry into the Moscow Trials and, for a time, served as Trotsky’s French translator. Some anti-Stalinists mistrusted Serge; he was one of the few oppositionists to survive the purges and perhaps the only one to escape to the West; but his inside accounts of the Soviet system were widely read. An edition of Russia After Twenty Years even appeared in English, translated by the Trotskyist leader Max Schachtman. Still, Serge was something of an oppositionist within the opposition. Highly critical of the sectarian feuding within the Fourth International, he insisted that the anti-Stalinist movement was not essentially Trotskyist (“we regarded the Old Man only as one of our greatest comrades”).

By the time Stalin and Hitler made their pact in 1939, Serge had been denounced by the Trotskyists as well as the Popular Front. The nomination of Midnight in the Century, his novel about exile in Kazakhstan, for the 1939 Prix Goncourt provided little solace. Less than a year later, he was forced to flee Paris as the Germans entered the city, and worked on The Case of Comrade Tulayev while awaiting an American visa in Marseilles. In March 1941, he crossed the Atlantic, along with André Breton, Anna Seghers, Wilfredo Lam, Claude Lévi-Strauss, and another 350 passengers on a boat with cabin space for seven. Denied entry to the US, he found asylum in Mexico where, one year before, Trotsky had been murdered by Stalin’s agents.

There Serge spent the remaining six years of his life, poor and isolated, organizing protests, publishing analyses of the international situation, dodging the sporadic attacks of Mexican Communists, writing his memoirs, and completing The Case of Comrade Tulayev as well as two other novels, The Long Dusk and Unforgiving Years. Only the The Long Dusk would be published in Serge’s lifetime. In November 1947, he hailed a Mexico City taxi, got in, and died.2

Written as they were in the aftermath of revolutionary failure, Serge’s novels all concern crises of faith. “What is ‘conscience’?” D wonders as he prepares to break with the Party, noting that he’s “behaving almost like a believer”—which, of course, he is. Conquered City, published in 1932, inaugurated this final, increasingly self-conscious phase in Serge’s writing, which culminated with Unforgiving Years. With these books, he trades the anonymous first-person narrator of his earlier work for the personal perspective of a single, dedicated revolutionary. Conquered City introduces this penultimate Sergeian character type in the form of Ryzhik, a reluctant member of the Cheka, the early version of the KGB. Ryzhik next appears in Midnight in the Century, exiled beyond the Urals but no less devoted to the Revolution, and turns up for the last time two thirds of the way through The Case of Comrade Tulayev, Serge’s fictionalized account of the Sergei Kirov murder and its aftermath. A chapter titled “The Brink of Nothing” has Ryzhik held in solitary confinement on a Black Sea collective farm—and thus spared arrest in the rigged, worldwide manhunt that follows the assassination of the Chief’s right-hand man. (Tulayev’s actual killer, an obscure clerk with an obscure motive, was also ignored.) Ryzhik is the last of his kind:

Prison had providentially protected him for over ten years, from 1928 on. A series of pure chances, such as save a single soldier out of a destroyed battalion, kept him out of the way of the great trials, of the secret investigations, and even of the “prison conspiracy”!

These three Ryzhik novels, directly preceding Unforgiving Years and forming a kind of Bolshevik trilogy, show how the experience of the old revolutionaries suggested the basis for a strange underground faith. Lost in the Gulag and deliberately starving himself to death, Ryzhik hallucinates about a powerful collective intelligence—the Bolshevik spirit that “brought together thousands of brains to perform its work during a quarter of a century, now destroyed in a few years by the backlash of its own victory, now perhaps reflected only in his own mind.”

Serge began writing Unforgiving Years in September 1945, hardly more than a month after the atomic bomb brought World War II to a close. The following January, writing to the French leftist Daniel Guérin, he referred to his current project as “a rather terrifying novel on the problems of consciousness in wartime,” and Unforgiving Years is the most self-conscious of Serge’s novels. The prose is thick with literary effects. The characters are acutely self-questioning, engaged as much with the effect of war on human consciousness as with the struggle of consciousness to change existing conditions when those conditions include war. Serge told Guérin that the novel was causing him physical pain; and D, like Serge, is suffering migraines. “Truth, stripped of its metaphysical poetry, exists only in the brain,” he thinks. “Destroy a few brains, quickly done!”

D shares Ryzhik’s martyr-like self-consciousness, but lacks his absolute purity. Instead, it is Daria, nineteen years old in 1919, who is the keeper of the faith. D associates her with the memory of fierce, dogged, uncomplicated zealotry: once upon a time, in the Revolution’s infancy, there was “surprise that enthusiasm could exist, that the new faith could be stronger than all else, action more desirable than happiness and ideas more real than old facts; that the world could be more alive than the self.” Her confidence in history ebbing as she speaks with a comrade in the ruins of Europe, Daria nonetheless echoes Ryzhik, her literary forebear, prophesying that “we have no life beyond working for a great common destiny.”

Serge’s female characters often seem abstract and Daria is no exception. But she is also something new in Serge’s fictional world. She’s a writer, albeit an amateur, with highly conventional thoughts on literature: “Let the imagination of poets and novelists put on a uniform and obey orders.” Exiled to Kazakhstan, however, Daria disciplines herself by keeping a journal that, as described by Serge, suggests a French new novel avant la lettre :

A curious document, this journal, whose carefully chosen words sketched out only the outer shapes of people, events, and ideas: a poem constructed of gaps cut from the lived material, because—since it could be seized—it could not contain a single name, a single recognizable face, a single unmistakable strand of the past….

Since it cannot express the least trace of sorrow or doubt or ideological thought, Daria finds working on this “thought puzzle in three dimensions” (with an “undefinable and secret” fourth one) exhilarating work. Pure as she is, perhaps even more so than Ryzhik, Daria writes not for the desk drawer but for the abyss. Summoned to Leningrad when the city comes under German siege, she burns her notebooks “without a twinge of regret.”

Daria is something of a literary critic as well. Her initial job in Leningrad is evaluating letters confiscated from German prisoners. Among these she discovers a tragic love story and, moved by a soldier’s hopeless passion for the doomed niece of a Ukrainian partisan, suggests to her superior that, revised by a writer, this narrative could be usefully published. The colonel is unimpressed: “Let our unionized pencil pushers do their own writing, they know their business.”

Unforgiving Years is composed of four linked sections. The first is a political thriller set in France a few months after the Munich Pact. Thereafter, Serge focuses on the war, as experienced by the inhabitants of two ravaged European cities. The novel’s second section belongs to Daria, exiled to Kazakhstan most likely as a result of her contacts with D in Paris. Four years later, she is released to work as an intelligence operative during the siege of Leningrad. (“Here the front line is everywhere, I warn you,” her unimpressed superior informs her.) The scene of Leningrad’s frozen rubble segues to one of utter urban destruction. Vaulting over the Eastern Front for the novel’s third and longest section, Serge describes the war’s final days as they are played out in a devastated suburb of Berlin. (“‘We’re going to be baked like potatoes in ashes,’ an old man calmly remarked.”) In a postwar coda, “Journey’s End,” Daria finally finds D himself, hiding from the NKVD on a coffee plantation in deepest Mexico.

Serge’s final book, like all of his novels, is characterized by a visceral sense of historical process. Birth of Our Power celebrated the newborn revolution by describing it as if through a child’s eyes. Conquered City opened in “prehistoric gloom” with Red Petrograd visualized as a settlement of cave dwellers, the action unfolding in the “primordial night” of Marxist prehistory, as Bolsheviks huddle in “oases of electricity” and engage in the primal bloodletting of the terror. Unforgiving Years (which had the elemental working title Sands, Snows, Fire) takes an even longer view. Paris slumbers under sentence of death, as oblivious as a city in the first reel of a Hollywood disaster film. Only D is cognizant of impending doom: “The avalanche rolls onward, and we’re in its path,” he warns his lover Nadine. Daria flies into a Leningrad that, despite the mastodon-sized truck that greets her, is not only pre- but post-historic:

There were caved-in roofs, whole stories exposed to the air and clogged with snow, gaping bays, stage-set façades of wood and sailcloth with rows of windows painted sketchily across them. A faded inscription read INTREPID CITY! TOMB OF——. As the banner was torn, its last words missing, the city could be the tomb of whoever you liked….

Daria notes the absence of the customary huge images of the Chief and finds it hard to imagine one in this setting:

How would he look? Standard confident smile, full cheeks, bushy mustache? No portraitist would dare to give him the only face appropriate for this city—hollow as a death’s-head, wet with tears.

Assigned work as a translator, Daria accompanies a commando unit on a mission to capture stray Germans. Beyond the city is a void where distant explosions amplify “the absolute silence of uninhabited expanses,” and the snow dunes suggest total extinction. (“The landscapes of dead planets must look like this,” she thinks; the novel’s metaphors often suggest science fiction.) After a confused skirmish on the white desert of the Neva River, the Soviets take a German prisoner; interrogated in a rude shelter, he turns out to be mad. Daria emerges from her evening’s work as if “from a grave,” into “a vast tomb.”

Serge then moves from Daria asleep in her makeshift communal apartment, dreaming that she is “a half dead woman,” to the vast necropolis of Berlin—a “ghostly city bristling with the skeletons of churches lashed by sky, wind, rain, and fire,” where after the previous night’s “hurricane,” the streets are “buried under a desert of scorched, blackened rubble, dusted with a powder as fine and light as mineral dew.” The prospect suggests nothing so much as Max Ernst’s epic canvas Europe After the Rain, painted between 1940 and 1942 when the artist, like Serge, was on the run from France to the New World.

Unforgiving Years has something of Ernst’s discomfiting lushness as well. Just as “the bogus reality of civilization reverted back to first principles” in bombed-out Germany, so the novel ends with a regression to the primal Mexican landscape. Lush and magical, populated by angelic Indian children, it is a “riotous disorder,” an unstable cosmos, the site of ancient sacrificial altars. These are given meaning by the images of death gods (“stark, attentive, abstract”) who, in another world, presided over Leningrad.

It may be that for Serge, the most terrifying aspect of Unforgiving Years was his own despair:

If there ever had been, if there ever were, somewhere in the world, another reality, it now remained in human memory as no more than a recollection, tinged more by doubt and sadness than by nostalgia.

“The past marked the older people most deeply,” he writes of the civilians huddled in a German bomb shelter. “People who seemed to have lived through so many events in the half century that they were probably exaggerating….” As the war ends in Germany, a friend of D’s, wandering in the ruins of Europe, looks to the heavens for a new revolutionary program. “But where are the men? Where are the grand ideas? Perhaps ideas are nothing but ephemeral stars. They point the way while they last, and then they go out….”

This Issue

October 22, 2009

-

1

Since then, The Case of Comrade Tulayev has returned to print (New York Review Books, 2004), while various small presses have brought out anthologies of Serge’s political pamphlets, his correspondence with Trotsky, and even his poems. An English-language biography, Victor Serge: The Course Is Set on Hope (Verso) by Susan Weissman, was published in 2001.

↩ -

2

That Serge evidently never told the driver his destination is appropriate to the speculation that surrounds the political thinking of his last months. Where would Serge’s anti-Stalinism have taken him? To judge from his American publications, his wartime politics oscillated between the left-wing social democracy of the Socialist Call and the right-wing social democracy of The New Leader. That Serge hoped to return to France may explain the ambiguous letter he wrote in 1947 to his onetime Popular Front enemy André Malraux, now a hero of the French Resistance and adviser to General de Gaulle:

↩