1.

In his entertaining memoir Younger Brother, Younger Son (1997), Colin Clark, a son of the art historian Kenneth Clark, recounts a story from his time working as a production assistant on the film The Prince and the Showgirl. To explain why Marilyn Monroe came across far more vividly on screen than her classically trained costar Laurence Olivier, Clark observed that, in front of the cameras, she knew how to speak a language an actor trained for the stage simply could not understand. To Olivier’s fury and frustration, the less the Hollywood goddess appeared to act, the more she lit up the screen. “Some years later,” Clark continues,

I experienced a similar situation when I took my father to the studio of the Pop artist Andy Warhol in New York. My father was an art historian of the old school, used to the canvasses of Rembrandt and Titian. He simply could not conceive that Andy’s silk-screened Brillo boxes were serious art.

Just as Monroe understood that you don’t have to act for the camera in the way the stage-trained Olivier defined acting, so Warhol realized that you don’t need to make art for an audience brought up on film and television in the way Kenneth Clark defined art. Actress and artist grasped that in the modern world, presentation counts for more than substance. The less you do, the greater may be the impact.

What defeated Kenneth Clark about Warhol’s paintings was not only their banal subject matter but also the means he used to make them. Before it is anything else, Warhol’s portrait of Marilyn Monroe is a silk screen, a simple reproductive technique in which the artist or craftsman stencils a design onto an acetate plate and then fits the plate into a meshed screen. When ink or paint is forced through the mesh, the design is transferred onto fabric or paper.1

Late in 1962 Warhol started to transfer silk-screen images onto canvas to make paintings. Other American artists, notably Roy Lichtenstein and James Rosenquist, were already painting images they found in comic strips and on billboards. It was not, therefore, Warhol’s subject matter that constituted the significant breakthrough in his early work but his decision to make fine art using a technique primarily associated with printmaking and with cheap commercial products such as T-shirts and greeting cards. Warhol’s friend Henry Geldzahler, a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, recognized that the artist’s two great innovations were “to bring commercial art into fine art” and “to take printing techniques into painting. Andy’s prints and paintings are exactly the same thing. No one had ever done that before. It was an amazing thing to do.”

After his early experiments painting cartoon characters and Coca-Cola bottles in the loose, drippy style of the Abstract Expressionists, Warhol liked the grainy, slightly out-of-register images produced by a silk screen because, he said, “I wanted something…that gave more of an assembly-line effect.” Warhol’s new paintings didn’t look as though they were painted by hand; they looked like mechanically reproduced photos in cheap tabloid newspapers.

A silk-screened image is flat, and without depth or volume. This perfectly suited Warhol because in painting Marilyn Monroe he wasn’t painting a woman of flesh, blood, and psychological complexity but a publicity photograph of a commodity created in a Hollywood studio. As Colin Clark’s anecdote suggests, you can’t look at Warhol’s Marilyn in the same way that you look at a painting by Rembrandt or Titian because Warhol isn’t interested in any of the things those artists were—the representation of material reality, the exploration of character, or the creation of pictorial illusion.

Warhol asked different questions about art. How does it differ from any other commodity? What value do we place on originality, invention, rarity, and the uniqueness of the art object? To do this he revisited long-neglected artistic genres such as history painting in his disaster series, still life in his soup cans and Brillo boxes, and the society portrait in Ethel Scull Thirty-Six Times. Though Warhol isn’t always seen as a conceptual artist, his most perceptive critic, Arthur C. Danto, calls him “the nearest thing to a philosophical genius the history of art has produced.”

Silk screen also enabled Warhol to produce serial images—that is, to choose a motif and then reproduce it repeatedly by silk-screening it in different color combinations. In a conventional printmaking process like etching, the artist makes a limited number of impressions, then destroys the copper plate. But Warhol’s series are not finite in this way. The number of finished works he made depended on how many he needed, or thought he could sell.

In Pop: The Genius of Andy Warhol, their fascinating study of Warhol’s rise from commercial artist to the most celebrated painter and filmmaker in 1960s America, Tony Scherman and David Dalton are clear that Warhol’s move from painting his pictures by hand to photo silk-screening was at the heart of his artistic achievement:

Advertisement

Traditional, manual virtuosity no longer mattered. The fact that Warhol could draw had no bearing on his art now: how an artwork was made ceased to be a criterion of its quality. The result alone mattered: whether or not it was a striking image. Making art became a series of mental decisions, the most crucial of which was choosing the right source image:—as Warhol would contend some years later, “The selection of the images is the most important and is the fruit of the imagination.”

Throughout the 1960s Warhol was personally involved in choosing, mixing, and applying the paint in most of the silk-screened works. But it was also his frequent practice to delegate the manual task of silk-screening an image onto canvas to his assistants Gerard Malanga and Billy Name. Malanga has said that in the summer of 1963 he was responsible for painting several canvases, including some Electric Chairs, entirely by himself. The following year Warhol told a journalist from Glamour magazine, “I’m becoming a factory,” and of course the building he worked in wasn’t called the “Studio” but the “Factory.”

Those who witnessed Warhol at work on a daily basis in these years—Malanga, Billy Name, his manager Paul Morrissey, and his primary assistant from 1972 to 1982, Ronnie Cutrone—all attest that, just as you’d expect from a mind as restless, inventive, and original as Warhol’s, the degree of his intervention in the creation of a painting varied—not only from series to series, but also from painting to painting within the same series.2

By the 1970s Warhol no longer had any sustained involvement in the mass production of his paintings. In his book about Warhol, Holy Terror, Bob Colacello quotes Warhol’s longtime printer Rupert Smith:

We had so much work that even Augusto [the security man] was doing the painting. We were so busy, Andy and I did everything over the phone. We called it “art by telephone.”3

One person they were calling was Horst Weber von Beeren, who was responsible for painting many of Warhol’s later works in a studio in Tribeca (and not at the Factory in Union Square). He has said that Warhol’s primary role in the creation of these paintings was simply to sign them when they were sold.4 The artist had come to realize that a painting could be an original Andy Warhol whether or not he ever touched it.

In fact, Warhol had long been familiar with this arm’s-length working method. In his days as a successful commercial fashion illustrator, his job was simply to make the drawing and hand it over to the art director, not to become involved in the layout. Scherman and Dalton quote Tina Fredericks, the art director at Glamour who gave Warhol his first New York job: “He didn’t care about that stuff—’Will my drawing be displayed big enough? Are you going to shrink it down?’ You could say to him, ‘We want this,’ and he’d just do it, he’d understand.”

Moreover, in his early fashion drawings Warhol developed a technique of blotting his initial design onto high-quality paper in such a way that his pen nib never touched the final drawing. “In fact,” Scherman and Dalton continue,

the original mattered so little to Warhol that he didn’t even draw it—his longtime assistant Nathan Gluck made the first sketch, rubbed it down to make the tracing, and hinged the tracing to the Strathmore [a brand of high quality drawing paper]. Andy entered only for the coup de grâce, the inking and blotting…. What remained constant throughout Warhol’s career, whether he drew, painted, or silk-screened photographs, was his fascination with the simulacrum, the copy, the second-generation image. In commercial art, the division of labor is the norm. When Andy began using it in fine art in the sixties, he undermined the myth of the auteur, the sole, and solitary, fount of art.

In this conceptual approach to making art, Warhol inherited the legacy of Marcel Duchamp, an artist he knew, admired, painted, and filmed. Like Duchamp’s ready-mades, the ultimate importance of a work by Warhol is not who physically made each object, but the ideas it generates. As the son of immigrants, Warhol in his early works returned again and again to the theme of America itself. What else are the paintings of cheap advertisements for nose jobs and dance lessons concerned with if not the American dream and the price of conformity it exacts? As soon as he’d examined the American obsession with celebrity and glamour in the portraits of Elizabeth Taylor and Marilyn Monroe, he was quick to show its race riots and electric chair. Unlike Duchamp’s, his was a highly public art, one that criss-crossed between high art, popular culture, commerce, and daily life.

Advertisement

Everything that passed before Warhol’s basilisk gaze—celebrities, socialites, speed freaks, rock bands, film, and fashion—he imprinted with his deadpan mixture of glamour and humor, then cast them back into the world as narcissistic reflections of his own personality. This is what makes him one of the most complex and elusive figures in the history of art. As Danto explains in his brilliant short study of Warhol, the question Warhol asked is not “What is art?” but “What is the difference between two things, exactly alike, one of which is art and one of which is not?”

2.

That is very like the question at the heart of a class-action lawsuit brought by the film producer Joe Simon-Whelan and other yet-to-be-named plaintiffs against the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., and the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board, Inc., which is the committee that was set up eight years after the artist’s death in 1987 to pronounce on the authenticity of his work. The case revolves around a series of ten identical silk-screened self-portraits from 1965 (Red Self Portraits), one of which is owned by the plaintiff and all of which the authentication board has declared are not by Warhol. The background to the case, which has become something of a cause célèbre among dealers, curators, and critics on both sides of the Atlantic, is discussed in detail in I Sold Andy Warhol (Too Soon), Richard Polsky’s breezy memoir of the art market before the economic crash. New developments can be followed in Simon-Whelan’s crusading Web site www .myandywarhol.com.

Anthony d'Offay

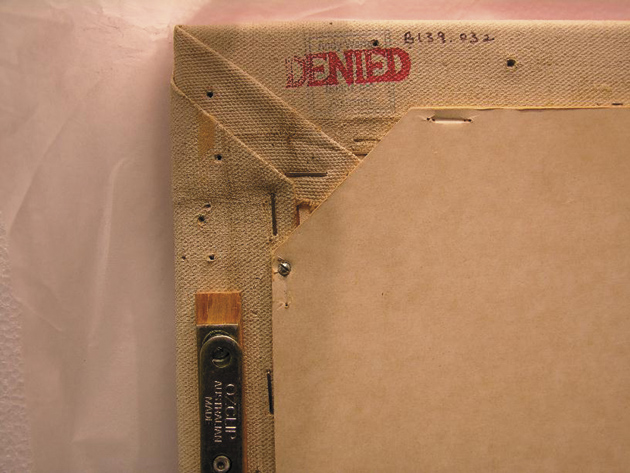

The back of Andy Warhol’s Red Self Portrait dedicated to ‘Bruno B.’ The Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board stamped it “DENIED” in 2003, asserting that it is not an authentic work by Warhol because he was not present when it was printed, although he signed and dated it on the bottom of the frame.

The Red Self Portraits are among Warhol’s best-known works, endlessly reproduced in books about the artist and on exhibition posters. Based on an image taken in an automatic photo booth, the portrait shows Warhol’s head and shoulders head-on and slightly from below, a pose much like those in two other important works from this period, the mug shots he used in Thirteen Most Wanted Men and the anonymous young man in his underground film Blow Job. Warhol presents himself as insolent and impassive, in the take-it-or-leave-it stance of the hustler or gangster. Out of register, like a color TV on the blink, the person in the portrait is a new kind of human being, one trapped in some fathomless, unreal televisual space, without physical mass or emotional depth. The dead, unseeing eyes in the self-portrait suggest that he was perfectly serious when he said, “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface: of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.”

As usual in making a silk screen, Warhol started by having the photo transferred to acetate plates. From these acetates he made two series of self-portraits. The first, which he began in the spring of 1964, consists of eleven self-portraits printed on linen, with several different background colors. These the authentication board considers genuine. The following year, a second series was printed from the same acetates on cotton, each with the same red background. The board denies the authenticity of this second series because Warhol was not present when they were printed.

What happened is that Warhol gave the acetates to the publisher Richard Ekstract in exchange for the use of the expensive Norelco video equipment that Ekstract had loaned him to make his first, groundbreaking videos. Prompted by Morrissey (who asked Warhol “why he didn’t save money by having the silk screen factory do the entire job with his instructions for all of his images”), Warhol told Ekstract to send the acetates to a commercial printer for silk-screening. Morrissey further says that Warhol spoke to the printer over the phone to give him specific, detailed instructions regarding the colors he wanted the printer to use. Both Warhol and Morrissey communicated with the printer, but Morrissey is clear that neither was present during the silk-screening process.5 After the printing, Ekstract returned the acetates to Warhol.

The second series is printed on white cotton duck. Its surfaces are slightly flatter, which makes the images look more machine-made than the ones in the first series because there is no evidence of the artist’s hand in the form of under-drawing or paint texture. The effect pleased Warhol. Sam Green, the curator of Warhol’s famous retrospective that opened at the ICA in Philadelphia on October 8, 1965, did not wish to include the Red Self Portrait in the exhibition

because it seemed too “manufactured” to go with the other paintings. Andy was pushing for it, though, because he said it exemplified his new technique for having works produced without his personal touch: he wanted to get away from that.6

The ten self-portraits in the second series were exhibited at a party Ekstract gave on September 29, 1965, both to celebrate the premiere of Warhol’s first video with Edie Sedgwick and to launch Ekstract’s magazine, Tape Recording. When the party was over, Warhol gave the self-portraits as a form of payment to Ekstract, who in turn took one for himself, gave two to the printer, and presented the rest to the people who had helped with the videotaping.7

So far, it might be possible to argue that whatever Warhol’s working practice was later in his career, the second series of self-portraits is not authentic because he was not present when they were printed. But this argument is undermined by one overwhelming fact: one picture in the series, now owned by the London collector Anthony d’Offay, is signed and dated by Warhol, and dedicated in his own handwriting to his longtime business partner, the Zurich-based art dealer Bruno Bischofberger (“To Bruno B Andy Warhol 1969”). Since the Renaissance, a signature is the way artists such as Mantegna and Titian acknowledge the authenticity of their work.

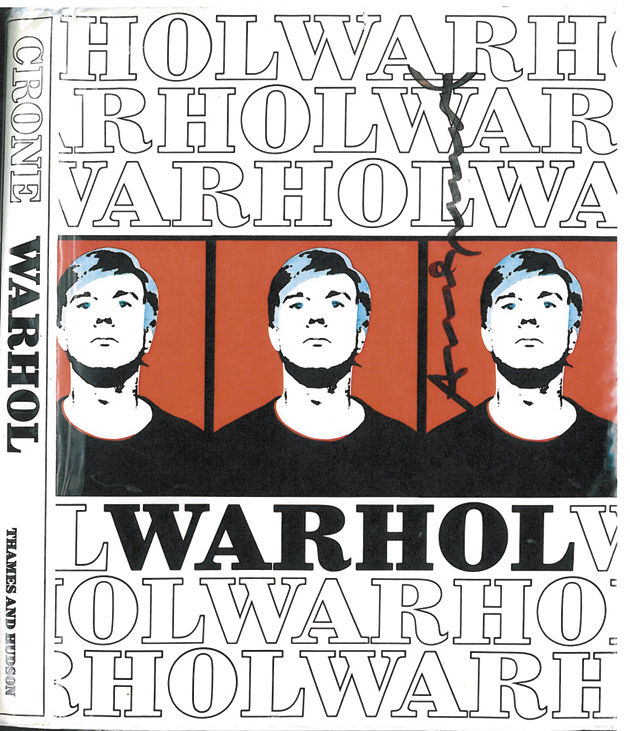

As if this were not enough to authenticate the work, the Bischofberger self-portrait appeared in Rainer Crone’s 1970 catalogue raisonné of Warhol’s work and is reproduced in color on the jacket. Crone is a highly respected independent scholar who worked closely with Warhol over a two-year period to compile this catalogue raisonné. Anthony d’Offay, who was Warhol’s dealer in London, writes in his statement about the “Bruno B Self-Portrait”:

When Andy Warhol came to London for his show with us in 1986, he signed in my presence our copy of Crone’s book in two places: one signature was across the dust-wrapper [cover] which reproduces our “Bruno B” Self Portrait eight times. The other was on the book’s half-title.

It is important to realise that Crone and Warhol together chose the “Bruno B” Self Portrait for the cover of the book and Andy Warhol’s signature across the “Bruno B” image on the dust jacket is further unequivocal evidence that Warhol not only was authenticating the work, but remained extremely proud of it.

On page 294, the catalog entry (no 169) for the “Bruno B” Self Portrait makes it clear that this is the picture that appears on the front cover of the book and was owned at the time by Bruno Bischofberger.

It is unthinkable that Warhol would have signed the book and the image if there was the smallest doubt in his mind that the work was not authentic. The combination of the dedication on the back of the painting with the choice of that image for the cover of the catalog raisonné, together with his further endorsement of the image by signing across it leave no room whatsoever for any doubt as to the authenticity of the work and the artist’s intention.

In the letter denying that d’Offay’s picture is genuine (May 21, 2003), the board writes, “It is the opinion of the authentication board that said work is NOT the work of Andy Warhol, but that said work was signed, dedicated, and dated by him.”

We are now in the realms of farce—and there is more to come. In 2004, the Warhol Foundation copublished its own updated catalogue raisonné with Thomas Ammann AG, a firm of Zurich-based art dealers heavily involved in the sale of Warhol’s work. In it, the authors, all of whom who are paid either by the Warhol Foundation or by Thomas Ammann AG, silently omit all mention of the Bischofberger self-portrait, even in a footnote or an appendix. A picture that existed in 1970 has been made to vanish: so much for scholarly rigor.

This may be the first time in history that a signed, dated, and dedicated painting personally approved by an artist for the cover of his first major monograph, which included a catalogue raisonné of his works, has been removed from his oeuvre by those he did not personally appoint. Although Rainer Crone has worked closely with the artist and possesses an important archive of the work they did together, at no time was he consulted by the compilers of the 2004 catalogue raisonné. In a statement of August 14, 2009, Crone writes, “I am aware of no other instance in which a revised catalog raisonné omits a hitherto accepted work without explanation.”

When challenged to explain why it continues to deny the authenticity of works in this series, the board replied in a letter of October 2004 that it

knows of no independent verifiable documentation from the period in question, 1964 through to 1965, to indicate or suggest that Warhol sanctioned or authorized anyone to make the work.

But how is it possible to say this? Quite apart from his signature and dedication, there are on record numerous statements from Warhol employees, assistants, and his manager all supporting the evidence regarding Warhol’s intentions about the series.

Few artists in the twentieth century were as restlessly experimental as Warhol. This ruling by the board represents a complete misunderstanding of the very nature of what he achieved, and how his approach to making his work changed Western art. Innovation has to start somewhere, and it is precisely because the 1965 Red Self Portraits were made without Warhol’s on-the-spot supervision that they are so critically important. They are the kind of transitional works museums and collectors particularly value because they show Warhol groping toward the working method he would adopt in the following decade, when his participation in the creation of his own paintings was often limited to choosing the image and signing the picture.

3.

The single most important thing you can say about a work of art is that it is real, that the artist to whom it is attributed made it. Until you are certain that a work of art is authentic, it is impossible to say much else that is meaningful about it. The separation of the real from the fake is the cornerstone on which our understanding of any artist’s work is based. The very nature of the silk-screening process makes Warhol a particularly easy artist to fake because there is virtually no difference between the appearance of a silk screen that Andy Warhol made with his own hands and one that an assistant might have run off after-hours. From early on, Warhol signed some works and used a stamp of his signature on others—but sometimes he didn’t sign a work at all.

The task of an authentication board for Warhol’s works is therefore not easy. But decisions like the one about the “Bruno B Self Portrait” at best raise doubts about this board’s competence and at worst about its integrity. For with assets in the region of $500 million worth of art, the Andy Warhol Foundation funds its charitable activities by selling the works it owns. This has left it open to the accusation that it is in the foundation’s financial interest to control the market in Warhols. Simon-Whelan’s lawsuit alleges that the board routinely denies the authenticity of works by Warhol in order to restrict the number of Warhols on the market and thereby to increase the value of its holdings.

Whether this is true or not I can’t say because, unlike any other authentication board that I’m familiar with, this one operates in secret, and is not required to divulge the reasons why a work has not been authenticated. Before it will look at a work submitted to it, the owners must sign a document saying that they will not challenge its verdict in court. Nor is the board obliged to reveal the reason for its decisions, even reserving the right to deauthenticate works that it has already authenticated, and to reinstate works it has already denied.

When a work is deemed not to be by Warhol, it is mutilated by stamping it in ink on the reverse with the word “DENIED”—thereby rendering the picture unsaleable even if the board later changes its mind. Although a lawyer for the board has said that no one forces applicants to submit works for authentication, no auction house or dealer will handle a work whose authenticity the board has questioned. A painting stamped DENIED is worthless.

Normally, authentication boards consist of independent experts who have spent their lifetime studying and familiarizing themselves with the work of a particular artist. Often they are made up of former studio assistants, a spouse, and art historians who have organized major shows and written extensively about that artist.8 But the two longest-serving members of the Warhol board are Neil Printz, a teacher at Caldwell College in New Jersey, and Sally King-Nero, curator of drawings at the Andy Warhol Foundation. We’ve already seen one example of the standard of their scholarship, and neither can be said to have independent status since both are also editors of the catalogue raisonné that is paid for with funds from the Andy Warhol Foundation and the Thomas Ammann firm (Thomas Ammann died in 1993).9 Vincent Fremont, a former Warhol assistant whom the foundation appointed exclusive sales agent for its paintings, and who personally takes a commission on each sale, is a “consultant” to the authentication board. In his lawsuit, Simon-Whelan says that defendants in his case also enforce their control over the market for Warhol works through a select group of powerful galleries and dealers who enjoy a special relationship with Fremont, the foundation, and the authentication board.

Over the years, a number of respected writers and scholars have joined the authentication board. Some have written about or helped organize exhibitions of Warhol’s work, but none has had expertise in the authentication of his work or firsthand knowledge of his working methods. In the light of cases like the Red Self Portraits, this has led to the suspicion that the real role of the outside scholars and curators has been to lend credibility to decisions made by Printz and Sally King-Nero in consultation with Fremont.

The Andy Warhol Foundation is packed with lawyers, and with hundreds of millions of dollars it has all the time in the world to fight lawsuits like Simon-Whelan’s, drawing them out until their opponents run out of money. So far, it has been impossible for ordinary people to challenge its decisions. But there may now be hope for those whose works have been denied without explanation and for no creditable reason. In May federal judge Laura Taylor Swain, in deciding against the Warhol Foundation’s motion to dismiss Simon-Whelan’s case, gave the plaintiffs the all-important right of “discovery” so that the authentication board’s long-suppressed methods of reaching its decisions can now be brought to light. If the plaintiffs are successful, this case has the potential to break the stranglehold the board has had on the authentication of Warhol’s work.

One person who will be following the case with close attention is Tate director Sir Nicholas Serota. In 2008 Anthony d’Offay sold his collection of contemporary art to the English nation (accepting £28 million for a collection then conservatively estimated to be worth £125 million), an act Prime Minister Gordon Brown called “the greatest gift this country has ever received from a private individual.” Among the many works d’Offay included in the donation was the self-portrait signed by Warhol and dedicated to “Bruno B.” Until its status is resolved, d’Offay has been forced to withdraw the painting.

—September 23, 2009

This Issue

October 22, 2009

-

1

Until the twentieth century the stencils used for silk-screening had to be cut by hand, but around 1910 a new technique of photo stenciling greatly expanded the usefulness of the silk-screening process in commercial design. Warhol would clip a photo from a newspaper or use a photo he’d taken himself. This would be sent to a lab to create a “negative” that Warhol would work on. When finished, this was sent to a silk-screening lab to create the screens that were use to print the image on the canvas. Multicolored prints required multiple silk screens.

↩ -

2

Of Warhol’s increasing reliance on assistants, Malanga says:

↩ -

3

Bob Colacello, Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up (Cooper Square Press, 1990), p. 478.

↩ -

4

BBC1 television program “Imagine,” January 24, 2006.

↩ -

5

Statement by Paul Morrissey made to the Andy Warhol Authentication board on November 1, 2002.

↩ -

6

Statement of Sam Green to the Andy Warhol Authentication Board, January 30, 2003.

↩ -

7

At this date an original painting by Andy Warhol was not worth very much, and Warhol often bartered his paintings for services—for example to settle dentist and lawyer’s bills, his restaurant tab at Max’s Kansas City, or in payment for arranging a recording session for his band, the Velvet Underground.

↩ -

8

In Warhol’s case one might expect to find scholars of the stature of Rainer Crone, Whitney curator Donna De Salvo, who organized Tate Modern’s magisterial Warhol retrospective in 2002, or Tom Sokolowski, who is director of the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh.

↩ -

9

Warhol: Paintings and Sculpture 1964–1969 volume 2, The Andy Warhol Catalog Raisonnee (New York and London, 1970), edited by Neil Printz and Sally King-Nero, both members of Andy Warhol authentication committee, and Georg Frie, an art dealer with Thomas Ammann AG, Zurich Fine Arts.

↩