Musée du Louvre, Paris

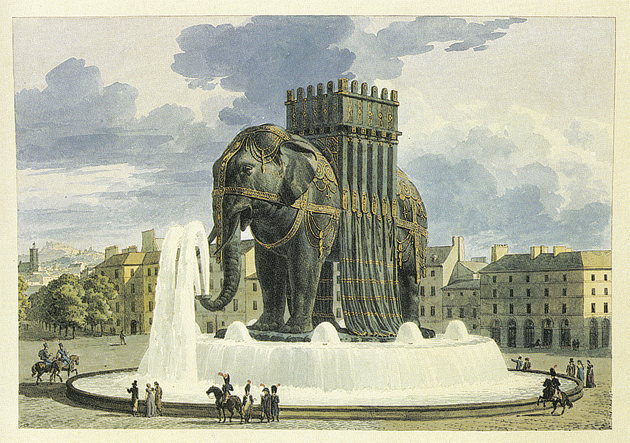

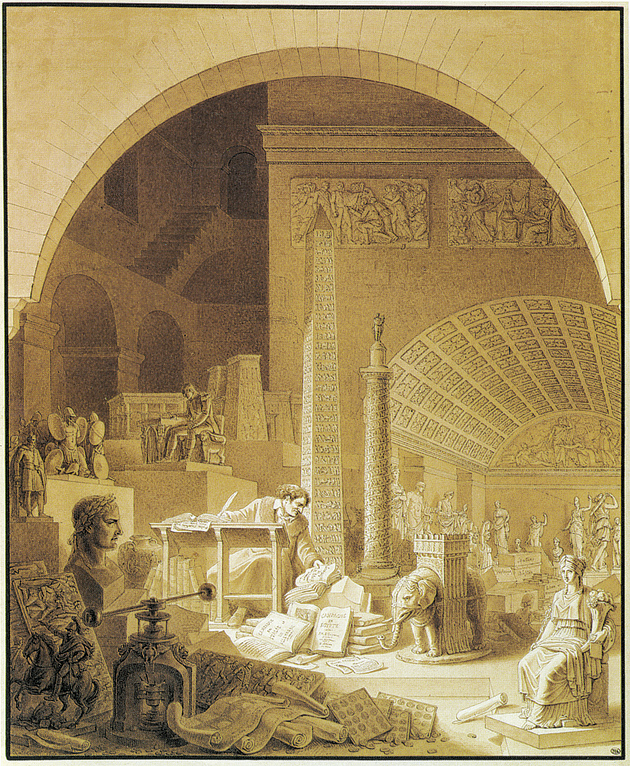

Benjamin Zix: Allegorical Portrait of Vivant Denon, 1811. Denon, whom Napoleon appointed the first director of French museums, is depicted at the entrance to the Louvre’s Salle de Diane, surrounded by, among other objects, the Vendôme Column; an obelisk planned for the Pont Neuf; the elephant fountain planned for the Place de la Bastille (see page 32); and two statues of Napoleon, a bust and a seated figure (left).

Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, pried off just under one half of the Parthenon frieze (some 247 feet) and added to it fifteen metopes and seventeen of the great sculptures from the east and west pediments, then shipped them to England, eventually to repose in the British Museum, where they remain as the clamor from the Greek government to return them to Athens grows ever more intense. Lord Elgin acquired a vast store of antiquities during his ambassadorship to the Sublime Porte—the Ottoman court in Constantinople—from 1799 to 1803, and after. He seems to have had some sort of a sales contract (now lost) with the Ottoman rulers of Greece (who had no interest in pagan monuments) that conferred some legitimacy on his removing sculptures from the world’s most famous temple (then a storehouse) and giving them refuge in London, where they were certainly better preserved.

But Elgin appears something of an amateur in the matter of the transshipment of artifacts from one country to another when you compare him to his French counterpart, Baron Dominique-Vivant Denon, who assumed the directorship of the Louvre—soon to be known as the Musée Napoléon—in 1802. The Louvre, as imagined by the French Revolution—it opened during the Reign of Terror—and then as realized by Denon under Napoleon, was the first encyclopedic public museum, dedicated to providing a new setting for art objects taken from their original location. They would be displayed in a way that would be instructive to a large public, as well as protective of the objects themselves.

The Louvre of this time was largely built on the systematic looting of Western Europe, and Egypt, of which Napoleon had made himself master. The acquisition of artworks was in fact stipulated in the various treaties Napoleon imposed on defeated regimes, and had all the subtlety of spoils of war. Teams of art experts dispatched from Paris followed closely in the wake of the victorious armies. The spoliation began before Denon’s directorship—the Belgian Campaign in 1794 brought in prized examples of Rubens; Napoleon’s invasion of Italy in 1796 led to the Pope’s ceding some one hundred works to France, including eighty-three universally admired sculptures from the Vatican and Capitoline museums. Denon as director was himself often on location, in Germany, Austria, Spain, and Italy, to inspect the goods.

The loot continued to arrive, and it became Denon’s task to organize, preserve, and make sense of it all. As Pierre Rosenberg, longtime director of the modern Louvre, writes in the catalog of the exhibition the museum devoted to Denon in 1999–2000, he was “Napoleon’s Malraux”—referring to the part played by André Malraux as culture czar during Charles de Gaulle’s presidency. The comparison is apt, in that Denon clearly had a gift for making the power he served understand that there was symbolic capital to be gained from cultural acquisition and display. As the exhibition catalog’s subtitle puts it, he was the eye of a ruler who had little aesthetic knowledge but grand ambitions for the visual imposition of power.

When a hundred cases of antiquities “acquired” in Italy arrived at the Louvre on October 1, 1803—without a single instance of loss or breakage—Denon made a short speech to the savants of the Institut de France, introducing the highlights of the collection. Master courtier that he was, he opened with adept praise for his lord and master:

Taken up at one and the same time with all genres of glory, the hero of our century, during the torment of war, required of our enemies trophies of peace, and he has seen to their conservation.

And what a haul of trophies it was, including the Capitoline Venus and Venus de’ Medici—the latter of which the Italians had hidden in Palermo, in vain: the French got it anyway (it went back to Florence, to the Uffizi, after Napoleon’s fall). France had no one quite up to Keats, whose emotion in “On Seeing the Elgin Marbles” could apply as well to Denon’s new possessions:

Such dim-conceivèd glories of the brain

Bring round the heart an indescribable feud;

So do these wonders a most dizzy pain,

That mingles Grecian grandeur with the rude

Wasting of old Time—with a billowy main—

A sun—a shadow of a magnitude.

That is not quite Denon’s style. He naturally—as author of one of the erotic masterpieces of French literature—chooses to describe the Venus de’ Medici (a Hellenistic and somewhat mannered piece considered the summa of beauty for his contemporaries):

Advertisement

Dressed in her modesty alone, her nakedness is pure. Her expression of happiness belongs to her perfection, to the plenitude of her being. The smile on her face is not yet that of voluptuousness, and yet happiness is already on her lips.

One can hardly blame Denon for his sycophancy toward Napoleon. Like a number of his contemporaries (he was born in 1747, and lived till 1825), he had had to learn how to survive through the most turbulent decades of French history. He evolved from being the Chevalier de Non (he came from minor nobility, of “the robe”—the magistrature—rather than “the sword”) to Citizen Denon to Baron Denon in the Napoleonic revival of titles. Under the Old Regime, his intelligence, good manners, and cultivation of useful connections earned him diplomatic missions to St. Petersburg (which, under Catherine the Great, was a kind of imitation of the French court) and Naples (seat of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies at the time).

When the Revolution broke out in 1789, he managed to be in Venice, where he had apparently planned to settle, to create his own engraving studio, and to marry his beloved mistress, Isabella Teotochi, herself the center of a literary and artistic salon. But he was expelled from Venice for suspected sympathies with revolutionary exiles, and set out for Florence. Then he discovered his name on the list of émigrés whose property could be expropriated, so he made a risky return to France during the Reign of Terror, and managed to put himself under the protection of the painter Jacques-Louis David, who enjoyed excellent standing with the Jacobins.

With the fall of the Jacobin Republic, Denon once again managed a graceful metamorphosis: he became friends with Joséphine de Beauharnais, then wife of the young General Napoleon Bonaparte. When Bonaparte undertook the conquest of Egypt in 1798—from personal ambition, and because those then governing France wanted to get him out of the country (he would return to stage his coup d’état the following year)—Denon was offered a place as chronicler, one of a number of “savants” sent to explore and create a record of this great if implausible and somewhat disastrous expedition. (This would be the occasion of the discovery of the Rosetta Stone—but it took another two decades to decipher it.) Though past the age of fifty, Denon accepted, embarked on the frigate Juno on May 1, 1798, and arrived in Alexandria on July 2, in time to take part in the Battle of the Pyramids. With characteristic concision and wit, he commented on the pyramids themselves:

One doesn’t know what ought to astonish the most: the tyrannical madness that dared to order their construction, or the stupid obedience of the people willing to lend their labor to such edifices.

During the campaign, under the command of General Desaix, Denon was often on the front line, stopping to sketch monuments and buildings and cities, as well as the occasional battle, working on a pad held on a drawing board supported across his saddle, dodging enemy musket balls. His energy and his cool under fire made him popular among the troops. He claims they held his drawing board on their knees and provided him with a sunshade when the army came upon the grandiose ruins of the city of Thebes, “a phantom so gigantic…that the army, coming in view of its scattered ruins, stopped of its own accord and, by a spontaneous movement, applauded….” French culture everywhere, even in conquest.

The result of Denon’s participation in the Egyptian Campaign was Voyage dans la Basse et la Haute Égypte pendant les campagnes du général Bonaparte (Travels in Lower and Upper Egypt During the Campaigns of General Bonaparte), a splendid account of his travels, illustrated by his engravings, that conveys the experience of conquest as cultural tourism. 1 Conquest and curiosity led him all the way up the Nile to Aswan and the first cataract. Denon is no militarist, though: after the pillage of one village—the women raped, the men robbed and dishonored—he notes: “War, how brilliant you shine in history! But seen close up, how hideous you become, when history no longer hides the horror of your details.”

What interests Denon most is the power of historical evocation; as he puts it when meditating in Alexandria on the Ptolomies, on Cleopatra, Caesar, Mark Antony, on the moment “the empire of glory gave way to the empire of voluptuousness,” he enjoys “the happiness of dreaming before great historical objects.” A contemporary described Denon as devoted to “two ardent but inoffensive passions, the love of women and enthusiasm for the arts.” To which one must add: the passion for intelligent travel and the eloquent recording, in word and image, of what he saw.

Advertisement

The result of the Egyptian Campaign and the Voyage he published in 1802 (there was earlier travel writing on Sicily) was his appointment by Napoleon as first director of French museums. Still today, when you enter the courtyard of the Louvre where I.M. Pei’s glass pyramid dominates the scene and look up toward the façade to your right, you can see “Pavillon Denon” inscribed above the majestic arcade. And in fact, the Louvre as we know it is in large measure Denon’s product. He conceived of the “Musée Napoléon” as the European capital of cultural artifacts, inevitably situated within the city that Walter Benjamin later called the “capital of the nineteenth century.” He saw no problem: the French were the masters of civilization, as of much of the Western world. It was far better for the spoils of Napoleon’s campaigns to be displayed in one place, available to enlightened and knowing connoisseurs, to young artists wishing to learn their trade, and to the general public.

This is where the Louvre—first the Muséum Français, then the Musée Central des Arts, then from 1803 to 1814 the Musée Napoléon—was something new in the world. There had long been talk of a gallery in Paris to display to a wider audience the royal collections of paintings and sculpture. The older private “cabinet” of the collector would be superseded by something more public. The Palais du Luxembourg had served as a first place of display for the royal collections, from 1750 to 1785, and its success among art lovers led to the project of using the vast Palais du Louvre, largely abandoned when Louis XIV moved the court to Versailles late in the seventeenth century.

But it took the revolutionary regime, in a law passed in 1791, to bring the museum into being. It opened on August 10, 1793, in the midst of the Reign of Terror—during Year I of the new Republic, on the anniversary of the deposition of Louis XVI, and some six months following his execution—on one of the Revolutionary days of celebration: the Fête de l’Unité. Lodged in a palace, it was symbolically a new nation’s creation for its people. The expropriation by the state of Church property (in November 1789), then of the possessions of the émigrés, the royal academies, and the Crown, yielded a good if unsystematic first collection.

The first creators of the museum did not know how quickly it would be enriched by the military prowess of the young General Bonaparte. But the arrival of new shipments of “trophies” quickly became a matter of public celebration. On July 27, 1798, for instance, the third convoy from Italy arrived in Paris, too late for the July 14 fête nationale but given its own ceremony, as the heavily laden wagons were paraded around the Champ de Mars. The only works unpacked for display during the parade were the four famous gilded bronze horses of San Marco, removed from their proud place above the entry of Saint Mark’s Basilica in Venice (the Venetians themselves had looted them from Constantinople in 1204), eventually set atop the new Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel constructed for that purpose outside the museum. Packed in another case lay the Apollo Belvedere, a Roman copy of another Hellenistic statue that, along with the Venus de’ Medici and the famous Laocoön—also taken from Rome—would long constitute the antique ideal and the sources of French neoclassicism.

The collections grew under Denon’s directorship. Napoleon’s victory at Jena in 1806 produced hundreds of paintings from Prussia. In 1809, Vienna ceded four hundred art objects. More collections came from Italy. Following the suppression of monasteries in Tuscany, Parma, and the Roman States in 1810, Denon was able to undertake a mission dear to his heart: the search for Italian “primitives,” as they were then called—the string of precursors to high Renaissance art. Paintings by Cimabue, Giotto, Pisano, Fra’ Angelico, Lorenzo di Credi, and Ghirlandaio made their way to the Louvre, as well as large numbers of works by Perugino—specially prized as the teacher of Raphael, who stood uncontested, as Vasari had taught, at the summit of art.

As Denon wrote to Napoleon on New Year’s Day 1803, the museum was to offer its treasures a “character of order, instruction, and classification.” The museum would indeed furnish “a history course in the art of painting.” It was a didactic instrument in the propagation of taste. In addition to works of the great masters, the museum should present “to the artist and the studious amateur” a “complete set” of the most distinguished representatives of all the diverse schools of painting “since the Renaissance of the arts up to our own time.”

Andrew McClellan in his Inventing the Louvre analyzes how Denon’s various decisions on hanging the profusion of works brought back from Italy (and from Flanders and Vienna) constituted an art history, bringing Italian Renaissance art to its climax in Raphael’s Transfiguration, then marking out subsequent individual assimilations of the great tradition, and thus claiming to propagate a master tradition for art. 2

Display itself became a new subject for thought, as the older norm of covering a wall with paintings gradually gave way to the idea of isolating each as an autonomous object of spectatorship. Lighting became a crucial question in a preelectric age: windows encroached on hanging space and created shadows. From early on, Denon wanted to eliminate windows and replace the roof with an ironwork and glass clerestory—a wish only eventually and partially realized by way of skylights at the base of the curve of the vault in the Grande Galerie. Mid-nineteenth-century renovations finally achieved Denon’s full glass ceiling for this central exhibition space.

The Louvre realized a kind of Kantian ideal for art as the object of disinterested contemplation. It had from the start its dissenters, notably the aesthetic and architectural theorist Quatremère de Quincy, who in 1796 led fifty artists in a protest against the removal of Italian masterpieces from their original settings. The battle over the museum as the place where art is stripped from its original context and shown in a new setting has been with us since the first years of the first museum. From the outset, the museum as collected booty had its justifications as well. One of the principal defenses—as with the Elgin Marbles—was the capacity of the museum to restore and conserve artworks that were often in a parlous state of disrepair. Restoration at the Louvre was an extensive enterprise: the flaking paint of Raphael’s Madonna di Foligno, for instance, was transferred between 1800 and 1802 onto canvas from the brittle and cracked wooden panel on which it was painted, in an astonishingly delicate and meticulous procedure.

When Napoleon fell in 1814, the first Restoration stipulated that the collections of the Louvre would be “respected” as “inalienable property of the Crown.” All that changed after Napoleon escaped from Elba and rallied his armies for the Hundred Days, which ended on the mournful plain of Waterloo. The second Restoration was more vengeful. The Duke of Wellington insisted in his turn that art was a legitimate military trophy, and the caissons began taking things back to their countries of origin (or elsewhere: the English grabbed the Rosetta Stone). Denon couldn’t abide the dissolution of his great institution, and resigned as director. Yet through administrative foot-dragging and diplomacy, and the incapacity of some of France’s enemies to act with the iron fist of Wellington, about half of the Napoleonic acquisitions remained, including, for instance, Veronese’s immense Marriage at Cana and Titian’s Christ Crowned with Thorns.

Denon survived after Waterloo. In a kind of retrospective gesture toward the Old Regime’s “cabinets of curiosities,” he created his own private museum in his Paris apartment on the Quai Voltaire, a place that those in the know sought out for a visit. It was often described, perhaps most succinctly by the novelist Anatole France, who noted that Denon had acquired a fifteenth-century reliquary into which he had placed his own sacred objects:

Some of the ashes of Eloise [Abelard’s Eloise, that is], taken from the tomb of the Holy Ghost; a piece of the beautiful body of Inez de Castro, that a royal lover had exhumed in order to ornament it with a crown; a few hairs from the gray mustache of Henri IV, bones of Molière and La Fontaine, one of Voltaire’s teeth, a lock of hair of the heroic General Desaix, a drop of Napoleon’s blood, gathered at Longwood [the Emperor’s final place of exile, on the island of Saint Helena].

It seems a parody in miniature of the nineteenth-century passion for the collection, including the encyclopedic imagination, something that you would ascribe to one of Balzac’s maniacal collectors or one of Maupassant’s fetishists, rather than to the elegant Denon. He also labored long at a Histoire générale des arts, which he never would complete. In addition to his Egyptian travelogue, he left a brief novella, first published in 1777, then again—revised and improved—in 1812: Point de Lendemain (No Tomorrow), one of the most elegant, and chaste, of erotic tales.

No Tomorrow falls into the tradition of the eighteenth-century “libertine” novel that culminates in Choderlos de Laclos’s masterpiece, Les Liaisons dangereuses, published five years after the first version of Denon’s tale. Like most of the works in that tradition, it’s about the rules of the game of seduction—and of being seduced. In No Tomorrow, it’s a twenty-year-old man who is expertly abducted for a night of refined pleasures by an older woman, who professes herself his mistress’s best friend, and is faithful, in her fashion, to both a husband and a steady lover. If the tale is all about the tactics of seduction and pleasure, it’s also about the ethics of the game played correctly. The high stylishness of the goings-on is matched by Denon’s impeccably elegant style, his capacity to suggest everything while naming nothing. If it is recognizably part of the world of dangerous affairs, it doesn’t have the sulphurousness that made Baudelaire say that Laclos’s novel burned like ice. It is happier in spirit. At the end, the woman returns her young lover to his previous mistress with this envoi:

Good-bye, Monsieur; I owe you so many pleasures; but I have paid you with a beautiful dream. Now, your love summons you to return; the object of that love is worthy of it. If I’ve stolen a few moments of bliss from her, I return you more tender, more attentive, and more sensitive.

That’s the structure of erotic exchange, of reciprocity: gifts given, and rewarded by dreams; moments of bliss stolen, but restored by return to one’s partner.

We know very little about Denon’s own sentimental life, other than his lifelong devotion to Isabella Teotochi, who remained in Venice while he was busy with the affairs of empire—which resulted in a long correspondence between them. He must, one guesses, have been familiar with the boudoir games he narrates so well. But Isabella may suggest something about his spirit, and that of No Tomorrow, when she writes of him: “a rare and perhaps unique case, he was always dear to men, although he was infinitely so to women.”

Everyone who encountered Denon found him pleasing—women only especially so. Isabella also says: “The constant joviality of his very amiable wit never offends the thin-skinned egotism of others, and never gets in the way of the unchangeable natural humanity of his heart.” An interesting tribute to an erotic writer. But then again, pre-Revolutionary France believed that eros was part of what Talleyrand famously called “the sweetness of life,” la douceur de vivre, undone by modern politics. You can find a statue of Denon in Père Lachaise cemetery, in Paris. He looks like the happy man his contemporaries said he was.

It is worth noting that the post-Waterloo exodus of Denon’s great collections back to Italy and elsewhere did not always result in the return of paintings and sculptures to the sites—often churches and convents—from which they were snatched, but rather their placement in museums, especially the Vatican collections. And if the Elgin Marbles were returned to Greece, they would go into the New Acropolis Museum, not back to the Parthenon. Despite the many arguments in favor of Quatremère de Quincy’s plea for art to remain in its original setting, a consensus has emerged that it is the fate of great art to end up in the museum—it’s neither safe nor viewable elsewhere. The argument no longer concerns the original setting versus the museum—by the mid-nineteenth century, every major European city had a museum, and the US would not be far behind—but simply which museum is to win out. Are the Parthenon sculptures specifically part of Greek culture, or should one accept the British argument that they belong to the culture of a Western civilization far broader in concept? Would returning them to Athens be an appropriate tribute to the origins of a tradition assimilated through English, French, Italian, and German education, or a surrender to self-interested nationalism? The dispute in any event is no longer about art but about cultural politics. 3

We seem to be stuck with the museum—and competing concepts of museology—as an essential part of our understanding of global cultural history. A walk through the Louvre, or the Metropolitan, always gives a dizzying yet deeply satisfying sense of command, of riches at one’s disposal. We might never have had the museum without cultural looting, but who would give it up today? On the wisdom of the museum, we should perhaps give the final word to that seasoned museum-goer Henry James’s fictional politician-turned-painter, Nick Dormer, hero of the novel The Tragic Muse, who visits London’s National Gallery to seek reassurance that he has chosen the right path. Faced with its works:

As he stood before them the perfection of their survival often struck him as the supreme eloquence, the virtue that included all others, thanks to the language of art, the richest and most universal. Empires and systems and conquests had rolled over the globe and every kind of greatness had risen and passed away, but the beauty of the great pictures had known nothing of death or change, and the tragic centuries had only sweetened their freshness. The same faces, the same figures looked out at different worlds, knowing so many secrets the particular world didn’t, and when they joined hands they made the indestructible thread on which the pearls of history were strung.

Where the museum is concerned, James’s eloquence seems triumphant.

This Issue

November 19, 2009

-

1

Denon’s Voyage, annotated by Hélène Guichard, Adrien Goetz, and Martine Reid, was reprinted by Gallimard in 1998. For a wealth of documents by and about Denon, see the anthology edited by Patrick Mauriès, Vies remarquables de Vivant Denon (Paris: Gallimard, 1998).

↩ -

2

See Andrew McClellan, Inventing the Louvre: Art, Politics, and the Origins of the Modern Museum in Eighteenth-Century Paris, p. 147. See also Andrew McClellan, The Art Museum from Boullé to Bilbao (University of California Press, 2008). Also of interest is Cecil Gould, Trophy of Conquest: The Musée Napoléon and the Creation of the Louvre (London: Faber and Faber, 1965).

↩ -

3

See, on these questions, Kwame Anthony Appiah, “Whose Culture Is It?,” The New York Review, February 9, 2006.

↩