The hopes for a peaceful, rational world, which had sustained so many of those who struggled through World War II, did not long survive the peace. The smiles of the San Francisco Conference, which, in June 1945, had agreed on the Charter of the United Nations, soon faded. Two months later the first nuclear bomb exploded over Hiroshima, radically changing the nature of power among the world’s strongest states.1 In February 1946 Josef Stalin, in a speech at the Bolshoi Theater, blamed the West and capitalism for World War II and assured his audience that the Soviet Union would be able, in the near future, “not only to overtake but even outstrip the achievements of science beyond the borders of our country.” Some four weeks later Winston Churchill made his Iron Curtain speech in which he denounced Soviet control of postwar Eastern Europe.

The capacity of the fledgling United Nations to keep and enforce the peace was based on the assumption that the leaders of the victorious wartime alliance would cooperate in this and other tasks. It soon became clear that this was an illusion. Not much later it also became obvious that the relations between the two superpowers were likely to become the greatest threat of all to the peace of the world. The situation came to be called the cold war, an ever-present possibility of nuclear Armageddon that dominated both international relations and the policies of Moscow and Washington. The world at large learned to live with, and worry about, a situation described, in another cliché, as the “balance of terror.”

It is useless, though tempting, to speculate on who was most responsible for the cold war and for the fantastic risk and expense that it entailed. The paranoia of Stalin; the aggressive language of the ideological struggle between communism and capitalism; the wild exaggerations and panicky assumptions, sometimes for short-term political objectives, that created dangerous reactions; the tendency, on both sides, to confuse military capacity with military intentions; the mutual ignorance and hostility that led to the most hazardous and expensive arms race in history—to none of these factors, or to the people involved in them, can be confidently assigned the entire blame for a phenomenon that held the world in dread and suspense for more than forty years. The contestants in the cold war, it now seems, were all caught up in a monstrous nuclear nightmare of fear, anger, suspicion, and irrationality that no leader seemed able to dispel.

That nightmare was occasionally interrupted by flashes of common sense. The fear that a regional conflict might trigger a nuclear war between the superpowers led to the development of international peacekeeping as a firebreak against the ultimate disaster. It now seems clear that both sides were convinced from an early stage that the use of nuclear weapons by large sovereign states against each other was virtually unthinkable, but also that only a balance of nuclear capacity could hold that conviction in reasonable equilibrium. Twenty years after the end of the cold war, we are seeing the first tentative official approaches to an infinitely complex and probably very distant objective, the total abolition of nuclear weapons.2

1.

Nicholas Thompson’s The Hawk and the Dove describes the careers and relationship of George Kennan and Paul Nitze, two men—perhaps the only two—who held responsible positions in the United States government or in public life throughout the cold war. Thompson has made this tale into a fascinating and highly readable book. He neither exaggerates the importance of his subjects nor underestimates their influence. Instead he gives a very human account of both their achievements and their failures. Wisely, he does not attempt to make a final judgment on their historical importance or on how other ideas and policies might have worked better. He describes two remarkable, and very different, men doing what they believed right among the infernal distorting mirrors of the cold war, and leaves readers to form their own conclusions.

Coming from very different backgrounds—Kennan’s impecunious and provincial, Nitze’s wealthy and cosmopolitan—the two had very different introductions to war and to international relations. Kennan, after military academy and Princeton, started as a clerk in the State Department and made himself, during his four pre-war years in the US embassy in Moscow, an outstanding expert on Russia and its Soviet regime. Nitze, after Hotchkiss and Harvard and a stint in Berlin studying the German economy, went to work at the powerful Wall Street firm of Dillon Read.3 Both men committed typical youthful gaffes, which were triumphantly dug up by their critics later on. Nitze, for example, is said to have “exclaimed at a dinner party in 1940” that he would rather live under Hitler than under the British Empire, while Kennan, disillusioned by changes at home during his absence in Moscow, had written an essay in which he advocated that the US should become an authoritarian state. They first met in 1943 on a train to Washington.

Advertisement

A visit to the bombed-out city of Hamburg had intensified Kennan’s revulsion at the monstrosity of modern war. After the Hiroshima bomb, he accompanied Averell Harriman to the Kremlin, apparently to persuade Stalin that nuclear weapons could help keep the peace. Nitze was a member of the United States Strategic Bombing Survey in the closing months of the war and had observed close-up the nuclear ruins of Hiroshima. His reaction was a practical one. The Soviets were sure to produce their own nuclear weapons and might well use them against the United States. The United States, therefore, until it could deter such an attack, must urgently prepare to survive it. In September 1945 Kennan, still in a hawkish mood about the detested government in Moscow, declared that there was nothing in the history of the Soviet regime to indicate that it would hesitate for a moment to use nuclear weapons against the US if it thought that would strengthen its own power position in the world.

2.

After Stalin’s Bolshoi speech, Kennan, once again posted to Moscow, was asked by Washington for an urgent analysis of the speech and of the current situation in Russia. His reply, on February 22, 1946, which came to be known as the “Long Telegram,” immediately became compulsory reading in Washington, and it transformed Kennan’s career. “My reputation was made” he wrote in his memoirs. “My voice now carried.” It also provided the conceptual foundation of US policy toward the Soviet Union for the duration of the cold war. “We have here,” Kennan had written,

a political force committed fanatically to the belief that with US there can be no permanent modus vivendi, that it is desirable and necessary that the internal harmony of our society be disrupted, our traditional way of life destroyed, the international authority of our state be broken, if Soviet power is to be secure.

However, “the problem is within our power to solve—and that without recourse to any general military conflict.” The solution was firm “containment”—primarily by political and economic means—of Soviet Russia’s inherently expansive tendencies. A talk at the Council on Foreign Relations amplified Kennan’s views and was published, signed “X,” in Foreign Affairs in July 1947.

As Secretary of State George Marshall’s chief of policy planning, Kennan became extremely influential and played a major part in, among other matters, the creation of the Marshall Plan. He was, however, to his great frustration, never able to snuff out the idea that his concept of containment could also be construed as a military policy. In his old age Nitze remarked that Kennan “always thought that I hijacked our Cold War policy of containment away from him. And I did, of course.” When Dean Acheson succeeded Marshall, Kennan brought in Nitze as his deputy at the policy planning staff and soon began to lose his own influence. Over Kennan’s opposition, Acheson supported the construction of the H-bomb. Kennan also vainly opposed the creation of NATO (it would, he said, divide Europe).

Still, in 1947, in a talk he later regretted and tried to suppress, he speculated about a US atomic attack that could cripple Soviet war potential. Two years later, in August 1949, he was horrified by the US reaction to the first Soviet explosion of an atomic bomb and by the apparently general belief that the Russians “conceivably could drop atomic bombs on this country.” He began to feel that his own warnings had created in Washington an excessively hostile, militaristic attitude toward the Soviet Union.

Nitze’s and Kennan’s views now went off in opposite directions for nearly forty years. Acheson, who respected both men, also judged their weaker moments presciently. After Stalin’s Bolshoi speech of 1946, Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, to whom Nitze had described the speech as a “delayed declaration of war on the US,” sent Nitze to see Acheson. After hearing Nitze’s alarmist views, Acheson told him he was “just seeing mirages.” “Paul,” he said, “you see hobgoblins under the bed. They aren’t there. Forget it!”4 Kennan’s 1957 Reith Lectures on the BBC were as controversial as they were widely read. Among other things, he suggested that American, British, and Russian troops should be withdrawn from Europe. Acheson was outraged that this and other suggestions in Kennan’s lectures were being reported as representing the views of the Democratic Party. “Most categorically they do not,” Acheson wrote in a press release. “Mr. Kennan has never, in my judgment, grasped the realities of power relationships, but takes a rather mystical attitude toward them.”

Advertisement

By 1950 Nitze had, in the words of one of Acheson’s biographers, Robert Beisner, become “a virtual alter ego of Acheson.” In that capacity he went to work on what was to be his equivalent of Kennan’s “Long Telegram,” the state document that was to ensure his place in history. This was the full strategic review that Truman had ordered from the State Department after the US decision to develop the H-bomb. As NSC-68, it prescribed the military version of the policy of containment. Although the United States was at the height of its power and influence, Nitze portrayed a country, and indeed a world, in the deepest peril from the Kremlin’s drive for world domination, and proposed a strategic military overhaul both nuclear and conventional on a huge and immensely expensive scale.

In his excellent book The Limits of Power: The End of American Exceptionalism (2008),5 Andrew J. Bacevich, a retired army officer and now a professor at Boston University, maintains that the “informal national security elite,” of which Nitze and James Forrestal were founding members, was responsible for an “atmosphere of permanent crisis” and the resulting weakening of the most important responsibilities of Congress, particularly its power to declare war. NSC-68 was, in Bacevich’s words, “one of the foundational documents of postwar American statecraft.” It helped to create, by persistent fear-mongering, a permanent militarization of US policy and ever-increasing military budgets. In Bacevich’s view the national security elite’s ideology, with its reliance on the false security of overwhelming military power, proved to be the most baleful form of American exceptionalism.

Nitze’s masterwork depended on an interpretation of Soviet intentions with which Kennan was beginning profoundly to disagree. The Korean War, starting in June 1950, showed that a small Communist state was willing, with support from the major Communist powers, to attack an American ally but that those powers were, if challenged, essentially cautious and able to negotiate peace with the United States. In fact it was Kennan, summoned back to Washington from Princeton, who made the first contacts—with the Soviet UN ambassador, Jacob Malik—to establish back-channel talks with the USSR on peace in Korea. In his gloomy, solitary, introspective way, Kennan had become increasingly disturbed at the course US foreign policy was taking. Instead of grandstanding and warring and constantly meddling in countries we did not understand, we should have, he wrote, “an attitude of detachment and soberness and readiness to reserve judgment.”

The Cuban Missile Crisis, in October 1962, provided an extraordinarily dangerous, but ultimately successful, test of this attitude. Nitze, with moderately hawkish views on how it should be handled, was a member of Excom, President Kennedy’s top advisory group on the crisis. He clashed with the President, who wished the standing order that no nuclear weapons could be fired without the President’s order to be urgently confirmed to all the US military services concerned. Nitze protested that this was unnecessary and was then told unceremoniously to confirm the order. After the Cuban crisis was over, his relationship with the Kennedys remained distant. The crisis also showed both that the Soviet leaders were willing to risk a secret installation of nuclear weapons close to the US and that they wanted to avoid a nuclear war.

3.

Both Kennan and Nitze opposed the escalation of the Vietnam War. Kennan, before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, made a comment that remains remarkably relevant today: “There is more respect to be won in the opinion of this world by resolute and courageous liquidation of unsound positions than by the most stubborn pursuit of extravagant or unpromising objectives.” Much as he may have sympathized with the antiwar protesters’ objectives, Kennan deeply disliked noise, violence, and lawlessness in domestic affairs. He was at heart an old-fashioned European conservative6 and at a time of national rage and uproar, he unwisely and unhistorically proclaimed that civil disobedience had no role in a democratic society. Distilling the furious public reaction to this remark, W.H. Auden responded that holding such a view is “to deny that human history owes anything to its martyrs.”

Neither Nitze nor Kennan was a central player in the Vietnam War period. Kennan supported the 1968 presidential campaign of Eugene McCarthy. (The New York Review reprinted his powerful supporting speech.7) Nitze, rejected at first by the incoming Nixon administration, set up, with Dean Acheson, the Committee to Maintain a Prudent Defense Policy with recruits like Richard Perle, Edward Luttwak, and Paul Wolfowitz. He was then appointed negotiator on the new Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT), thereby, as Thompson puts it, being given “a chance to try to bargain away the system his charges were working so hard to save”—a task he impressively performed.

Nitze was an immensely knowledgeable negotiator and problem solver, with an extraordinary grasp of detail and a firm conviction that only a stable balance between the two nuclear arsenals could keep the peace. The United States wanted to shrink the Soviet arsenal; the Soviets wanted to limit US missile defense technology. Nitze’s conduct of the highly technical SALT talks was paralleled by Kissinger’s simultaneous talks with the Soviet ambassador to the US, Anatoly Dobrynin, on the same topic. Nixon wanted a SALT success in time for the 1972 elections, and Brezhnev needed one to relieve the exhausted Soviet economy. In May 1972 Nixon and Kissinger arrived in Moscow to sign, with Brezhnev, the SALT agreements that reflected in large part Nitze’s two years of negotiation. Thompson writes, “Given the political benefits of the deal,” Nitze and his SALT delegation were left “to remain in Helsinki, out of the limelight.”

Kennan’s two-volume memoirs, published in 1967 and 1972, were extremely successful with the public and seemed to show how right he had been about major events, from Stalin’s 1930s purge trials, which he saw as Stalin’s murderous attempt to establish supreme power, to the advantages of negotiation, as with Nixon’s opening to China in the early 1970s. Kennan admired “détente” and Kissinger’s pragmatism in negotiations with the Chinese and the USSR. “Henry,” Kennan wrote, “understands my views better than anyone at State ever has.” Nonetheless, as the decade dragged on, Kennan fell into one of his dark moods about the fate of the world. He feared that US policy was becoming totally militarized and would inevitably lead to an armed showdown. In The Cloud of Danger (1977) he launched a withering attack on the United States and its policies. The book also presented a very different view of the Soviet leaders, as “an old and aging group of men, commanding—but also very deeply involved with—a vast and highly stable bureaucracy.” Unluckily for Kennan, Pravda approved, writing that Kennan’s “views have substantially evolved in the direction of common sense.”8

Meanwhile Nitze, with no place in the Carter administration, set up yet another citizen-lobbying group, the Committee on the Present Danger.9 It included among its members Ronald Reagan, Dean Rusk, Saul Bellow, Richard Perle, Richard Pipes, Elmo Zumwalt, and Norman Podhoretz. Thompson calls it “a holding pen for the men and women later called neoconservatives.” To emphasize the perils of Soviet supremacy, Nitze took to carrying around models of nuclear weapons. The Soviet ICBMs were ten inches long and black; US weapons were five inches long and white and were often laid down horizontally, while the Soviet ones pointed aggressively skyward. He was determined to derail the SALT II negotiations being pursued by the Carter administration and finally succeeded, deeply humiliating Carter.

Kennan, at first impressed by Ronald Reagan, was soon disenchanted. He was horrified by the “Evil Empire” speech and the demonization of Soviet leaders, the lack of communication with Moscow, and the vast and growing stockpiles of increasingly powerful nuclear weapons. He proposed an immediate 50 percent reduction of nuclear stockpiles, followed by a further two-thirds cut in the size of arsenals, and invoked “our duty to the great experiment of civilized life on this rare and rich and marvelous planet.” He led a group including McGeorge Bundy and Robert McNamara that urged a “no first strike” policy. When Nitze publicly denounced this idea, Moscow thought it meant that Reagan was planning a first strike.

Nitze, now the negotiator on intermediate-range missiles in Europe, was anxious to show this was not the case. When he was actually given responsibilities as a negotiator, he did not, as Thompson makes clear, follow the more aggressive policy he sometimes advocated while out of office. He disobeyed his instructions and took his Soviet counterpart on the famous “walk in the woods” in the Jura mountains in a desperate effort to get agreement on limiting nuclear weapons in Europe, a move that was strongly disapproved of by practically everyone else. The story, leaked to The New York Times on Nitze’s seventy-sixth birthday, made him, in the public eye, a new champion of peaceful solutions.

Reagan’s Star Wars (Strategic Defense Initiative) speech of 1983 surprised some of his advisers almost as much as it did Moscow, where SDI was seen as an offensive weapon that nullified the principle of Mutually Assured Destruction and violated the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. With Gorbachev’s succession to the Soviet leadership in March 1985, the long nightmare began slowly to be dissolved. Nitze’s most dramatic involvement as a nuclear negotiator was at the October 1986 meeting between Gorbachev and Reagan in Reykjavik. Reagan, contrary to expectations, came close to proposing nuclear disarmament. After a strong start the talks broke down over Star Wars.

Nitze was “exhausted, run down and crushed.” George H.W. Bush did not retain him, and Nitze played no further part in the START negotiations that, by reducing the stocks of strategic nuclear weapons, began to reverse the process that Nitze himself had spent much of his life driving in the opposite direction.

4.

By writing a surprisingly personal account of two men who lived their professional lives at very high intensity, Thompson has given human form to the most terrifying aspect of the cold war, the nuclear arms race. The atomic bomb, created in panic in the mistaken belief that Hitler would shortly have nuclear weapons, used, for the first and, it is to be hoped, last time, to defeat Japan, and copied by a paranoid Soviet Union, became the dark center of the mutual hostility and fear between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Thus, until quite recently, we lived in a time when many of the most powerful and brilliant people in the world spent their energy and talent, and huge sums of public money, on developing weapons that, if used, would have almost certainly destroyed orderly life on this planet. That it was impossible, for forty years, for the two superpowers to discuss this most lethal of threats to all life in a rational manner must rank, in retrospect at least, as the greatest foolishness and the greatest shared irresponsibility in history. The Hawk and the Dove reminds us poignantly of this fact.

Kennan and Nitze ended up as friends, although not very close ones, after nearly forty years of disagreement. Nitze declared, in 1999, that we should eliminate our entire nuclear arsenal, a change of heart of the kind that seems usually to occur in public men only after retirement. I am not sure that the two men actually “complemented” each other, as Thompson puts it. Kennan formulated the basis for handling, for nearly forty years, the most important challenge of US foreign policy. Nitze tried to apply the formula to a high-stakes military and psychological gamble, at huge cost, as Kennan argued, to civilian society, the US economy, and even to an orderly Russia. It is a miracle that the world avoided a near-terminal disaster.

For much of their careers, Nitze and Kennan represented opposite positions, morally, politically, and militarily. Nitze won out in the short term, Kennan in the long term. When the cold war was clearly at an end, it was Kennan who was awarded the Medal of Freedom. “George is a happy man now,” Arthur Schlesinger wrote in his diary. “He basks in an atmosphere of belated but heartfelt recognition and approval.” Nitze too, although more grudgingly, was praised as the designer of the military strategy that may have kept America safe, but there were many who thought that American belligerence had encouraged Soviet belligerence and therefore intensified the arms race. Both men were sincerely convinced that their course was the right and patriotic one. Thanks particularly to Gorbachev and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet regime, things eventually worked out reasonably well, and no one could say with absolute certainty which one was right.

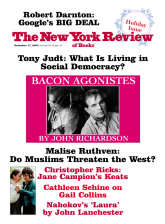

This Issue

December 17, 2009

-

1

In a forthcoming book, Bomb Power: The Modern Presidency and the National Security State (Penguin, 2010), the historian Garry Wills advances the thesis that “the Bomb altered our subsequent history down to its deepest constitutional roots.”

↩ -

2

As of January 2009, the US had 2,702 warheads deployed and Russia 4,834 (this figure includes 2,047 nonstrategic warheads). SIPRI Yearbook 2009, Summary, p. 16.

↩ -

3

Thompson provides much enjoyable trivia. At Milwaukee’s Fourth Street School, one of Kennan’s classmates was Golda Mabovitch, later Golda Meir; Nitze’s roommate in Berlin was Alexander Calder.

↩ -

4

James Chace, Acheson (Simon and Schuster, 1998), p. 149.

↩ -

5

See my review in these pages, March 26, 2009.

↩ -

6

Thompson reveals that in the 1940s Kennan had proposed a Foreign Service School with strict discipline and uniforms.

↩ -

7

George F. Kennan, “Introducing Eugene McCarthy,” The New York Review, April 11, 1968.

↩ -

8

In 1952, Kennan, talking to a reporter in Germany after four disagreeable months as ambassador in Moscow, described the treatment Americans received in Moscow as about like being interned in Germany during the war. He was immediately declared persona non grata by Stalin, who evidently could not accept being compared, by implication, with Hitler.

↩ -

9

Nitze was an indefatigable institution-builder. As early as 1943, he and Christian Herter had founded the School of Advanced International Studies, now Johns Hopkins’s highly respected SAIS.

↩