For most Israelis, the fact that the Hamas government in Gaza was firing missiles deliberately aimed at killing Israeli civilians is enough to justify whatever Israeli soldiers did in Gaza last January. In the public media within Israel, to say nothing of the government’s pronouncements, the ongoing international debate on questions of human rights abuses in Israel and the charges of war crimes put forward by the report of Richard Goldstone for a UN fact-finding mission have produced little more than the usual disingenuous accusations of anti-Semitism. Even Moshe Halbertal, an unusually cogent Israeli participant-observer, takes the Goldstone commission to task for trying to link the Gaza campaign to the wider context of the occupation and Israeli policies toward the Palestinians. “Why,” he asks, “should a committee with a mandate to inquire into the operation in Gaza deal with the Israeli–Palestinian conflict at large?”1

There are, in my view, problems, distortions, and lacunae in the Goldstone report—some of them resulting from the fact that the Israeli government refused to cooperate with the commission. At the very least, Israeli testimony, by both ordinary soldiers and higher-ranking officers, might have modulated the sweeping conclusions in three of the most damning chapters of the report: “Chapter X. Indiscriminate Attacks by Israeli Armed Forces Resulting in the Loss of Life and Injury to Civilians”; “Chapter XI. Deliberate Attacks Against the Civilian Population”; and “Chapter XIII. Attacks on the Foundations of Civilian Life in Gaza.”2 I also agree with Halbertal that Hamas benefits from an almost eerily neutral tone in the report.3

But the report’s attempt to link whatever happened in Gaza with what has been going on in the West Bank for the last forty-two years is wholly justified. The political background to the report is, before all else, a cultural and moral one. I do not believe that a society can disenfranchise, dispossess, and effectively dehumanize large numbers of people living between Jenin and Hebron without this process influencing the way it conducts a war in Gaza. No one who regularly visits the Palestinian territories controlled by Israel has to speculate about whether or not Israel is engaged in the routine abuse of human rights.

Such abuse is the very stuff of the occupation—a daily reality exacerbated above all by the endless hunger for more land and the ever-expanding settlement project. That reality has been amply documented by Israeli human rights organizations such as B’Tselem and, more recently, Yesh Din (which offers legal aid to Palestinians), as well as by a large corpus of writings produced by firsthand witnesses, including those discussed in my bookDark Hope.4

Since the publication ofDark Hope and, in particular, since the formation of the present Israeli government last spring, the situation on the ground has markedly deteriorated. Here is one relatively minor example: the imposition of Closed Military Zones by local Israeli commanders in the territories has had the effect—and, quite likely, the intention—of keeping Palestinian villagers and Israeli peace activists away from Palestinian fields. Establishing these zones has become standard practice; we encounter them nearly every week in the south Hebron hills. Palestinian lands that are not cultivated for three years automatically revert to state ownership; Palestinian farmers and shepherds are frequently chased off their lands at gunpoint by Israeli settlers and sometimes gain access to these fields or grazing grounds only when accompanied by Israeli activists.

The Israel Supreme Court ruled in 2004 that it is illegal for the army to declare Closed Military Zones as a routine practice, especially if this means distancing Palestinian farmers from their lands. But the court’s writ, backed up by a directive issued by the army’s own legal adviser for the territories, doesn’t have much practical effect. Just four weeks ago, I spent a day in detention at the Qiryat Arba’ police station together with seven other activists precisely because a local commander declared the fields of the village of Samu’a, which border on the “illegal outpost” of Asahel, a Closed Military Zone.

Israeli peace groups and human rights activists often challenge the actions of the Israeli army, the border police, the Civil Administration, and other government authorities in court or in nonviolent protests in situ, with occasional successes; mostly, however, we fail, as we did recently in East Jerusalem, where large-scale settlement projects, including the expulsion of Palestinian families from their homes, are now in progress. There is, no doubt, something to be said for the fact that these matters are at least freely discussed in the Israeli press and are adjudicated by a still functional legal system—although the record of Israeli courts in matters relating to the occupation and, above all, the settlements is, in my view, a dismal one.

Advertisement

For decades now, the courts have allowed the settlement enterprise to proceed unimpeded by significant legal constraints, despite its evident criminal nature under international law. The courts have failed to stop the large-scale expropriation of private (also communally owned) Palestinian lands. They have let rampant violence by settlers throughout the territories, and very conspicuously in the city of Hebron, go largely unpunished. They have sanctioned the fencing off of Palestinian villages into tiny, discontinuous enclaves cut off from markets, schools, hospitals, and workplaces. The list of such failures by the courts could easily go on and on.

To be fair, as mentioned earlier, there is often a wide gap between the rulings of the courts, including the Supreme Court, and the reality of how those rulings are implemented, especially within the occupation system, which has been thoroughly penetrated by settlers.5 But at heart the problem is not, after all, a legal one: rather, it reflects our deeper vision of ourselves in the world and our ability to see, to imagine, and to acknowledge the suffering of other human beings, including those aspects of their suffering for which we are directly responsible. It is also important to note that the public debate itself has its limits, as you can see by the recent attempts to silence Dr. Neve Gordon of Ben-Gurion University6 or the no less invidious government campaign to dry up international funding for Shovrim Shtika (“Breaking the Silence”), the remarkably courageous group of ex-soldiers who have exposed recurrent acts of army violence against Palestinian civilians that they witnessed in Hebron and elsewhere in the territories. Shovrim Shtika has also meticulously collected soldiers’ testimony about what they saw or did during the Gaza campaign last December and January.

So does it help me, as an Israeli, to be told—by Robert Bernstein in aNew York Times Op-Ed—that, so far as human rights abuses are concerned, Israel’s record is considerably better than that of various neighboring “authoritarian regimes with appalling human rights records”?7 It does not. As an Israeli, I would like to know, to take only one example selected at random, if Israeli soldiers did or did not deliberately shoot a handcuffed, unarmed Palestinian named Iyad al-Samouni in the legs on January 5, 2009, and then prevent members of his family from helping him, with the result that Iyad bled to death—as reported in the Goldstone report, paragraphs 736–744. Either the report of the circumstances of Iyad’s death is true, or it is not. If it is false, then we would like to know about this.

If it is true—and the Goldstone committee found the Palestinian testimony credible—then as an Israeli I have a stake in seeing the guilty soldiers brought to justice; and if they were only “following orders,” a line of defense no Israeli should ever want to adopt, then I would want whoever issued the order to be held responsible, even if (especially if) it were the Minister of Defense himself. This case is one of many and is also part of the wider setting mentioned earlier. Israel’s steadfast refusal to investigate such cases by an official, high-level commission of inquiry or its equivalent—combined with its refusal to cooperate with UN investigators—looks alarmingly like an admission of guilt.

As prophesied long ago by the late philosopher Yeshayahu Leibowitz and others, the occupation—and above all the settlement project—have profoundly eroded the moral fiber of Israel, corroded central institutions of the society, and undermined our integrity as a political community. None of this happened in a vacuum; the “other side” has much to atone for as well. But even I can remember a time when charges of war crimes were not simply sloughed off by Israel’s leaders, when military mistakes that cost innocent civilian lives were acknowledged as such and elicited expressions of sorrow, and when Israeli courts clearly articulated the principle that a soldier has not only the right but indeed the duty not to carry out an order that is at odds with his conscience as a human being or with basic human values.

I remember vividly an eloquent apology offered on national television by then Chief of Staff Mota Gur for accidental civilian casualties caused by shelling during Operation Litani in Lebanon in the spring of 1978. One might also recall the time in late 1982 when some 400,000 ordinary Israelis came out to demonstrate in Tel Aviv because of Israel’s indirect responsibility, as occupying power, for the Sabra and Shatila massacre in Beirut. Times have changed.

—November 18, 2009

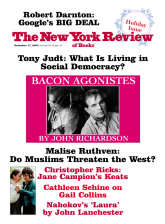

This Issue

December 17, 2009

-

1

”The Goldstone Illusion,”The New Republic, November 6, 2009.

↩ -

2

The full text of the report, titled “Human Rights in Palestine and Other Occupied Arab Territories: Report of the United Nations Fact-Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict,” is available online at www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrcouncil/specialsession/9/FactFindingMission.htm. See the précis in section 61 of the Executive Summary: “Taking into account the ability to plan, the means to execute plans with the most developed technology available, and statements by the Israeli military that almost no errors occurred, the Mission finds that the incidents and patterns of events considered in the report are the result of deliberate planning and policy decisions.” This means that in the eyes of the commission, Israel deliberately targeted civilians and destroyed civilian infrastructures in order to punish the population of Gaza and enhance Israel’s deterrent.

↩ -

3

For example: “These acts [missile and mortar attacks from Gaza on Israeli cities] would constitute war crimes and may amount to crimes against humanity” (section 108). Note the slippery subjunctives: “would constitute,” “may amount to.” The phrases recur in section 1950.

↩ -

4

University of Chicago Press, 2007; see the review in these pages by Avishai Margalit, December 6, 2007.

↩ -

5

It has been over two years since the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the army must move the separation barrier at the village of Bil’in westward in order to restore the village lands to their rightful owners; so far the barrier has not been shifted by a single inch.

↩ -

6

See the “Open Letter to Rivka Carmi, President, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel,” inThe New York Review, November 5, 2009.

↩ -

7

”Rights Watchdog, Lost in the Mideast,” October 19, 2009.

↩