—It is this hour of a day in mid June, Stephen said, begging with a swift glance their hearing. The flag is up on the playhouse by the bankside. The bear Sackerson growls in the pit near it, Paris garden. Canvasclimbers who sailed with Drake chew their sausages among the groundlings.

Local colour. Work in all you know. Make them accomplices.

—Shakespeare has left the huguenot’s house in Silver street and walks by the swanmews along the riverbank. But he does not stay to feed the pen chivying her game of cygnets towards the rushes. The swan of Avon has other thoughts.

Composition of place. Ignatius Loyola, make haste to help me!

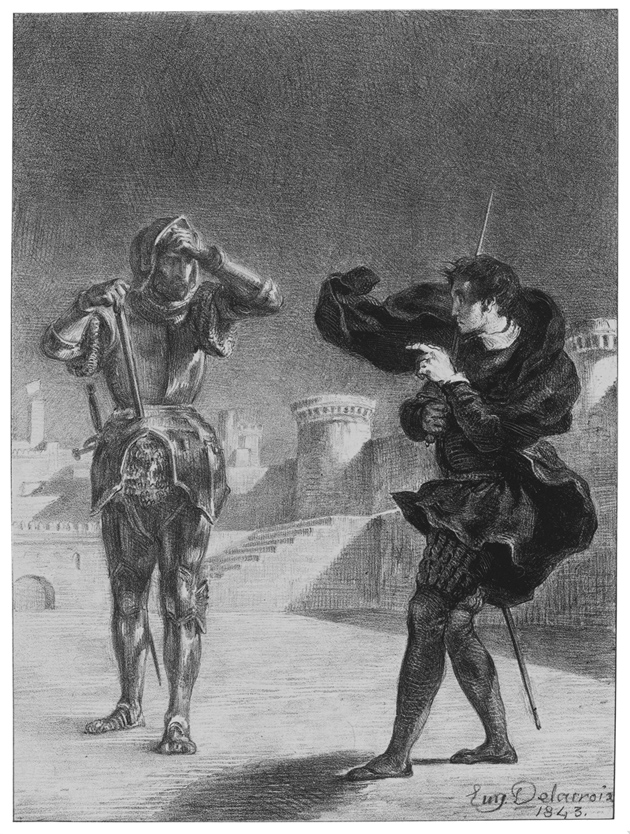

So begins the poet Stephen Daedalus’s celebrated fantasia on the life of Shakespeare in the “Scylla and Charybdis” episode of James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922). Stephen asks his listeners to imagine Shakespeare on the way from his rented rooms on Silver Street to the Globe Theatre, situated alongside other places of entertainment by the banks of the Thames. An actor as well as a playwright, Shakespeare is about to perform the part of the Ghost in Hamlet, a part that deeply preoccupies him, for—as Joyce spins out the yarn—it arose from a hidden trauma in his own life. In creating the role of the Ghost, he consciously drew upon this trauma, and in speaking the Ghost’s words onstage to Hamlet, he was covertly addressing his own dead son Hamnet. To his son’s spirit the grieving father disclosed the terrible family scandal: “you are the dispossessed son: I am the murdered father: your mother is the guilty queen. Ann Shakespeare, born Hathaway.”

With whom did Shakespeare’s wife betray their marriage bed? Given the dark premise of the Hamlet story—Queen Gertrude was evidently having an affair with her brother-in-law—it follows logically, Stephen suggests, that Ann’s adulterous lover must have been one of William Shakespeare’s three brothers, Gilbert, Edmund, or Richard. Of Gilbert, there is no trace in the playwright’s work, but Edmund and Richard are, after all, the names of Shakespearean villains. It must have been one of them. What more proof could anyone need?

There is, it should quickly be said, not a shred of actual evidence that Ann Shakespeare was unfaithful to her husband of thirty-four years, let alone that she committed adultery with one or more of her brothers-in-law.1 What Stephen Daedalus invokes in place of evidence is the plot of Hamlet and, more generally, the presence of “the theme of the false or the usurping or the adulterous brother or all three in one” in so many of Shakespeare’s plays:

The note of banishment, banishment from the heart, banishment from home, sounds uninterruptedly from The Two Gentlemen of Verona onward till Prospero breaks his staff, buries it certain fathoms in the earth and drowns his book.

This thematic omnipresence, a virtual Shakespearean signature, invites Joyce to weave his biographical speculation into a novel that broods brilliantly for hundreds of pages on adultery, a dead child, and a husband’s banishment from his wife’s bed.

Once the relevant Shakespearean materials are introduced, Joyce—or rather, his character Stephen—no longer insists on their literal truth:

—You are a delusion, said roundly John Eglinton to Stephen. You have brought us all this way to show us a French triangle. Do you believe your own theory?

—No, Stephen said promptly.

So much for the truth-claims of this exuberant exercise in Shakespeare biography.

But in the meantime Joyce has revealed deftly some of the key operating procedures of all but the briefest and most ascetic of such biographies. The writer of a life of Shakespeare starts building, as Joyce’s Stephen does, from the small number of more or less verifiable facts. Shakespeare was an actor: that much is known. His name was printed, along with the names of his fellow actors, in the list of the players that was included in the first collected edition of Ben Jonson’s plays (1616) and of his own (1623). These lists, unfortunately, do not specify the particular parts that the individual actors played, so there is no secure evidence of the actual roles Shakespeare took, either in his own plays or in those of others.

By the time someone—the biographer and editor Nicholas Rowe, in 1709—thought to investigate, anyone who might have seen Shakespeare on stage was long dead, and even family memories, passed down from generation to generation, had faded. “Tho’ I have inquir’d,” Rowe reported, “I could never meet with any further Account” of Shakespeare’s career as an actor “than that the top of his Performance was the Ghost in his own Hamlet.”2 That third- or fourth-hand report (hardened into a certainty in Stephen Daedalus’s account—another typical feature) is then brought together with the fact that Shakespeare’s only son, who died at the age of eleven in 1596, was named Hamnet, a name almost interchangeable with that of the hero of Shakespeare’s tragedy. The stage is set, and the illusionist can begin to perform.

Advertisement

“Local color. Work in all you know.” Since the eighteenth century, when steadily mounting interest in his achievement began to call forth a spate of biographical books and essays, the documented facts about Shakespeare’s life—for the most part, traces left in bureaucratic records—have almost always been supplemented by facts culled from the social, cultural, and intellectual history of Elizabethan and Jacobean England. According to legal documents unearthed only in the early twentieth century, in 1604 Shakespeare was renting rooms in London at 13 Silver Street, in the house of Christopher Mountjoy, a French-born Protestant (Huguenot).3 Around that small biographical fact—recorded only because the Mountjoys were embroiled in a lawsuit in which their lodger Shakespeare was called as a witness—Joyce arrays a mass of details meant to give it the thickness of a lived life: the swans along the Thames; the bearbaiting pit at Paris Garden, on the south bank of the river; the flag flown at the nearby Globe Theatre, to signal performances that afternoon.

To these details Joyce casually adds the epithet—swan of Avon—conferred upon Shakespeare by his friend and rival Ben Jonson, along with the name of the most famous Elizabethan bear, Sackerson (referred to in The Merry Wives of Windsor), while with the colorful coinage “canvasclimbers,” lifted from Pericles, he gives Drake’s sailors, glimpsed on shore as sausage-chewing members of the audience, a sudden physical presence. The whole rhetorical performance is calculated, as Stephen Daedalus says to himself, to make his listeners enter, almost without knowing it, into the act of conjuring up the missing person of the playwright. “Make them accomplices.”

Trained by Jesuits, Stephen draws upon a technique called by Ignatius Loyola ” composition of place,” whereby a person is enabled “to see with the eye of the imagination” an absent object or person by forming a vivid mental image of the place where that object or person is found. This technique is the traditional mainstay of Shakespeare biographies. Joyce draws most of his Elizabethan details from three such biographies—Frank Harris’s The Man Shakespeare and His Tragic Life-Story (1909), Sidney Lee’s A Life of William Shakespeare (1898), and, above all, Georg Brandes’s splendid two-volume William Shakespeare: A Critical Study (1898)—and the many biographies written over the course of the last century have succeeded admirably in adding more and more such details. But despite feverish attempts to comb the archives and find further documentary records of Shakespeare’s life, very little has turned up in the last century that was not already known to Joyce.

The paucity of new discoveries has not inhibited the constant writing of new biographies. (I am guilty of one of them.) The lure is almost irresistible, and with good reason: the aesthetic power, the enduring cultural importance, and above all perhaps the uncanny personal intensity of Shakespeare’s poetry and plays make anyone drawn into their orbit want to know more about their maker. Never mind that he left so few traces of himself. Never mind that none of his personal letters or notes or drafts survives; that no books with his marginal annotations have turned up; that no police spy was ordered to ferret out his secrets; that no contemporary person thought to jot down his table talk or solicit his views on life or art. Never mind that Shakespeare—son of a middle-class provincial glover—flew below the radar of ordinary Elizabethan and Jacobean social curiosity. The longing to encounter him and know him endures.

With Soul of the Age: A Biography of the Mind of William Shakespeare, Jonathan Bate, professor at the University of Warwick and author of several distinguished scholarly studies and editions of Shakespeare, has now entered the lists of those who set out to address this longing. He duly reviews many of the now-familiar biographical records that permit us to reconstruct how a young man without inherited wealth, university education, or a powerful social network could become successful, rich, and widely celebrated as a writer of stupendous distinction.

The celebration was not, or not only, the work of later ages. Already during his lifetime enraptured students memorized his love poems—“I’ll worship sweet Mr. Shakespeare,” a character in a college play of the time effuses, “and to honor him will lay his Venus and Adonis under my pillow”—and the appearance of his name on the title page of a playbook helped increase sales. More published plays were attributed to Shakespeare than to any other contemporary dramatist.4 A mere seven years after his death, in the prefatory poem to the collected edition of his plays now known as the First Folio (1623), the notoriously prickly Ben Jonson likened his deceased friend and theatrical rival not only to some of the greatest English writers—Chaucer, Spenser, and Marlowe—but also to the greatest playwrights of classical antiquity, Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. It was Jonson who gave Shakespeare the epithet Bate adopts as his title: “Soul of the Age.”

Advertisement

What distinguishes Bate’s account of this success story from most of the others produced in recent memory is the degree of his uneasiness about his own project. To be sure, he makes a valiant if fitful effort to do what he evidently thinks is required of him. “Winter 1563. Mary Shakespeare, born Mary Arden in the village of Wilmcote on the fringes of the Forest of Arden, is pregnant for the third time.” A moment later, shifting tenses, he tries a slightly different tack: “A few months later, Chamberlain Shakespeare’s first son would be born into a new world.” And after a sentence or two more, another verb tense marks yet another tack: “William Shakespeare grew up to become the father of twins and a dramatist who mingled comedy and tragedy, low life and high, prose and verse.”

Nervous shifts of this kind in sentences not exactly weighed down by the complexity of their ideas suggest a writer uncomfortable with what he is doing. Bate makes periodic stabs at writing a kind of action prose, usually in the form of a self-conscious run of sentence fragments—

The office of William Cecil, Lord Burghley. First minister of state, eyes and ears of Her Majesty. A table piled high with state papers; a steady stream of officials coming in with reports, requesting signatures on letters for dispatch out into the regions.

—but his heart is clearly not in them. One can almost hear the sigh of relief when he is able to relax into a more comfortable professorial mode: “Tudor intellectuals were so intrigued by this idea of Englishness as a mixture of county and national identity that they invented a new art form to express it: ‘chorography,’ or the geographical and historical description of a particular region.” But then, he reminds himself, he is not in the classroom, and he forces himself back to an enterprise very little to his liking.

Given the paucity of the evidence, that enterprise demands speculation, imaginative daring, and narrative cunning, but these are all qualities that arouse the scholar’s suspicion and anxiety. Bate’s attempts to enter the life-world of his subject are underwhelming: “Even if you grow up to become the greatest writer the world has ever seen, you begin like every other baby, mewling and puking. When William Shakespeare was born in April 1564, he doubtless mewled….” Young Shakespeare grew up—for even if you are destined to be a splendid playwright, you need to grow up—and “then he got the acting bug.” Casting about somewhat desperately for a way to breathe life into this moribund tale, Bate briefly tries a scene from a 1950s sitcom:

John Shakespeare, coming from a class where “idleness” was a sin, would have subscribed to the common view that actors were little better than vagabonds…. When John heard that his son had become employed in the theater, he would have been flabbergasted.

But it won’t work: Bate knows that there is no evidence for casting the Shakespeares as a family in Father Knows Best, and he quickly abandons the effort.

Still, he cannot simply throw over the whole enterprise. Another staple of popular biography is the resonant historical parallel, and Bate pluckily gives that a try too. “The small but proud island nation is under threat. Europe has been taken over by a ruthless empire with ambitions of global domination…. The invasion force has gathered. Now England can only wait, watch the Channel, and pray.” Enter Winston Churchill, cigar in hand. “This was their finest hour.” But no, it is August 1588, with the Spanish Armada poised for invasion. The Queen, dressed in armor, reviews the troops at Tilbury and rallies her shaken subjects. The Queen’s armor was meant, Bate claims, to evoke Pallas Athene, for “Classical Athens was a city famed for everything that the English nation held dear: democracy, debate, learning, sport, poetry, theater, empire.” What? Democracy in 1588? Held dear by whom? Even poetry and theater were hardly without their fierce enemies. Bate knows that his whole list, with the possible exception of empire, is an absurd mismatch. So once again he beats a hasty retreat.

Where does this leave the beleaguered biographer? In a no-man’s- land of swirling hypotheticals and self-canceling speculations; stillborn claims that expire at the moment they draw their first breath. Here is a brief sampling: “It is not outrageous to imagine…” “Could it have been at the same age…?” “Could he be the voice not only of Guy but also of William…?” “Could he have been Shakespeare’s apprentice in the acting company?” “It seems more than fortuitous that…” “It is unlikely to be a coincidence that…” “Guesswork of course, but I have a hunch that…” “I have an instinctive sense that…” “It is hard not to notice…” “We cannot rule out the possibility that…” “Could it then be that…?” “One of the two could easily have been…” “He may well have been there…” “The players may well have been…” “This could have been the occasion…” “It is not beyond the bounds of possibility that…” “…requires us to countenance the possibility that…”

Toward the end of this very long book, Bate wonders why Shakespeare did not take more care to oversee the publication of his works. “We simply do not know.” Sensing that this simple declaration of ignorance will not do, he gropes nervously for a theory: “If the 1609 sonnets really were unauthorized, and if they were perceived to smack of lechery or even sodomy, Shakespeare may have shied away from the world of print.” At last the germ of a claim. It is not a claim that most Renaissance scholars would accept—it “smacks” more than a bit of Victorian prudery—but at least it stakes out an argument: the sonnets, with their homoeroticism and their allusions to venereal disease, were meant to remain in private circulation; their unauthorized publication embarrassed their author and make him leery of appearing any longer in print. Yet the bugle immediately sounds for a retreat: “But that takes us back into the realm of wild surmise.”

Why this level of skittishness in a learned scholar who is at the pinnacle of professorial distinction and who has, after all, freely chosen to write on this subject? In part, of course, phrases like “could have” and “may well have” are the stock-in-trade of Shakespeare biographies, but the spectacle of anxiety in Bate’s book goes well beyond the ordinary signals of caution. Perhaps it is a function of the professional policing that is characteristic of certain corners of the academic world, Shakespearean scholarship among them. There are people who make it their business to try to catch mistakes, even the tiniest ones, and who take intense pleasure in shaming those guilty of carelessness, rashness, or ignorance. Scholarship depends on this policing—its absence haunts the Internet and makes much of what circulates on it worthless—yet it can also produce a painful aura of fear and inhibition, especially among those whose very gifts make them most sensitive to criticism.

But this, as Bate would say, is wild surmise. When Soul of the Age is at its best, it is liberated altogether from the self-imposed obligation of biography and engaged in something completely different: a genial, confident, relaxed, and slightly random survey of Shakespeare’s perspective on the “seven ages of man.” Sketched in a famous speech in As You Like It, the scheme of the seven ages—infant, schoolboy, lover, soldier, justice, pantaloon, and second childishness (“sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything”)—was not Shakespeare’s invention, and it cannot be mapped in any coherent way onto Shakespeare’s actual life.

Bate does not claim that Shakespeare served as either a soldier or a justice, and it is a bit difficult to conjure him up, even in his retirement, as a lean and slippered pantaloon. But that is what frees Bate from the pressures of constructing a plausible narrative. He can abandon the idea that there is anything in Shakespeare’s life to interest a serious person and devote himself to assembling brief discussions of the plays and poems, institutional and historical tidbits, fragments of cultural history, and excerpts from ancient and contemporary philosophy that have a loose bearing on one or another of the seven ages of man.

Bate is particularly good at teasing out the rhetorical training Shakespeare would have shared with his fellow schoolboys—“elaborate figures of verbal symmetry—syllepsis, antimetabole, zeugma, threefold amplificatio (otherwise known as tricolon)”—and at constructing a list of the books he is most likely to have prized. As one might expect from the author of a fine study on Shakespeare and Ovid, Bate is highly alert to all that Shakespeare owed to the Metamorphoses, and he also writes well on the playwright’s pervasive debts to Plutarch’s Lives and to Montaigne’s Essays. But Shakespeare, in Bate’s view, “traveled light.” This means not only that Shakespeare could, Bate thinks, have fit all of the books that mattered to him into a small chest but also that he rarely plunged very deeply into anything he read. Bate’s Shakespeare is, like the thief Autolycus in The Winter’s Tale, a snapper-up of trifles, an inveterate skimmer.

It would be difficult to know from this “biography of the mind of William Shakespeare” that its subject was one of the greatest thinkers of his age as well as its greatest writer. Profound thought is not, after all, one of the stations in the conventional seven ages.

Soul of the Age ends with a flurry of quotations from an early-seventeenth-century reader of the Folio who jotted down his reflections in the margins. The marginalia in this Folio, which is now in Japan’s Meisei University library, have been conveniently transcribed by Akihiro Yamada, from whose edition Bate liberally quotes. “Counsellors can not command the Weather.” “Subiects s[h]ould not prye in the affaires of state.” “Warre is phisicke to restlesse young men surfetted with ease.”

Very little is particularly interesting in the annotations, but that is the point: they can serve as a conspectus of the thought typical of the age. And they are as well a kind of figure for what Bate himself has done. He has written a florilegium, a commonplace book, pieced together out of fragments of social, cultural, and above all intellectual history. This is a perfectly reasonable and useful thing to do. The fault is only to suggest that the result enters very deeply into Shakespeare’s mind, let alone that it reveals anything significant about his life. For that, the reader is better served indulging in the extravagant fantasies of James Joyce.

This Issue

December 17, 2009

-

1

See Germaine Greer, Shakespeare’s Wife (HarperCollins, 2007).

↩ -

2

Nicholas Rowe, “Some Account of the Life, &. of Mr. William Shakespear,” in The Works of William Shakespeare, edited by Rowe (London: Jacob Jonson, 1709), Vol. 1, p. vi.

↩ -

3

The documents were unearthed in London’s Public Record Office by an American scholar, Charles William Wallace, associate professor of English at the University of Nebraska, and his wife Hulda. The significance of the discovery has been richly mined in Charles Nicholl, The Lodger Shakespeare: His Life on Silver Street (Viking, 2008). Since the Wallaces’ discovery was made in 1909 and announced to the world (in Harper’s Monthly) in 1910, Joyce’s Stephen Daedalus could not in fact have known this biographical detail of Shakespeare’s life at the time of the fictional conversation on June 16, 1904.

↩ -

4

”A True, perfect, and exact Catalogue of all the Comedies, Tragedies, Tragi-Comedies, Pastorals, Masques, and Interludes, that were ever yet printed and published, till this present year 1661,” in the library of Trinity College, Cambridge, includes, under Shakespeare’s name, “Cromwels History,” “John King of England 2nd part,” “The London Prodigal,” “The Merry Divel of Edmonton,” “Mucidoris,” “Old Castles life and death,” “The Puritan widow,” and “The Yorkshire tragedy.” The singularity of Shakespeare’s achievement—his strategy for conjoining high literary ambition and popular success—is analyzed brilliantly in a new book by Jeffrey Knapp, Shakespeare Only (University of Chicago Press, 2009).

↩