The rise and triumph of the Soviet dissident movement in the second half of the twentieth century surely ranks as one of the finest episodes in Russian cultural history. Its significance lies not just in its civic achievements as a hugely effective political opposition, but also in a body of literary work fully worthy of Russia’s rich traditions. We need only think of the metaphysical poems of Joseph Brodsky or the dialogic novels and documentary prose of Alexander Solzhenitsyn (both winners of the Nobel Prize), the modernist fiction and essays of Andrei Sinyavsky, who wrote under the name of Abram Tertz, the polished stories of Varlaam Shalamov, and the penetrating memoirs of Nadezhda Mandelstam, Lydia Chukovskaya, and Evgenia Ginzburg, not to speak of the works of such diverse writers as Vassily Grossman, Venyamin Erofeyev, Vladimir Voino- vich, Inna Lisnyanskaya, and the singer-songwriters Bulat Okudzhava and Alexander Galich (and these are only a few of a great many gifted writers). If the classic nineteenth-century authors of Russia marked the golden age of Russian literature, and the modernists of the early twentieth, its silver age, the writers of the latter half of the twentieth century constitute a kind of bronze age and a fully worthy restoration of a great tradition, despite having to work in conditions of repression and censorship that far exceeded anything their predecessors had to cope with before the October Revolution.

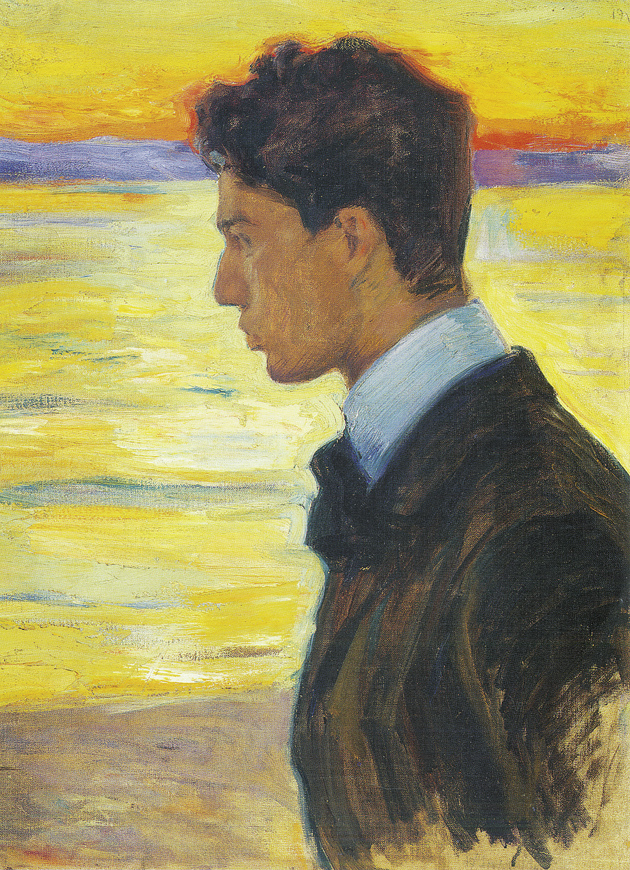

Such were some of the thoughts aroused by Vladislav Zubok’s new book with its enticing title, and by his eloquent prologue, in which he discusses the extraordinary publication of Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago outside the Soviet Union in 1957 and the implications of this event for Soviet cultural and political life. No one would call Pasternak a “dissident” in the usual sense of the word, yet his stubborn independence and his decision to allow foreign publication of his novel set an important precedent in post-Stalinist Russia. Although he was forced by government pressure to reject the Nobel Prize awarded to him in 1958, the damage was already done. Disregarding the reality of Pasternak’s situation, Solzhenitsyn later upbraided him for rejecting the prize, but without Pasternak, Solzhenitsyn’s own path would have been harder. As it was, Soviet censorship was breached for the first time after World War II, and Pasternak remained alive to tell the tale.

Pasternak also proved Stalin right about one thing. If you ease up on absolute censorship, you never know where things will end. Zubok understands this, just as he understands Pasternak’s significance as a taboo breaker and a living link to the moral and literary traditions of the Russian past. But Zubok, educated in Moscow during the last years of the Soviet Union and now a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute in Washington and a history professor at Temple University, has a peculiar understanding of Pasternak’s legacy. He is little interested in Pasternak’s natural heirs in the dissident movement, and connects the poet instead to what might be called the “loyal opposition” of Soviet intellectuals, that is, to the postwar intellectual nomenklatura—the officially recognized writers, artists, and editors—and especially its liberal wing. This sleight of hand is unsettling, for his heroes prove to be Alexander Tvardovsky, editor of the leading literary journal of the period, Novy Mir (which published Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich); Konstantin Simonov and Konstantin Paustovsky, two conventional novelists and memoirists; and Ilya Ehrenburg, the mercurial Jewish author and journalist.

From the younger generation he selects the novelist Vladimir Dudintsev (author of the “thaw” novel Not by Bread Alone), the poets Yevgeny Yevtushenko and Andrei Voznesensky, and the prose writer Vassily Aksyonov. To be fair, Zubok’s dense narrative encompasses a cast of many hundreds of writers, editors, painters, sculptors, scholars, critics, and literary bureaucrats of diverse views, and the liberal writers don’t take up a great deal of space. The point for Zubok is that they were leaders—ambitious, progressive, and rebellious (up to a point)—but the problem is that their other defining feature was their loyalty to the system.

This virtual exclusion of the dissidents from the equation takes some getting used to, especially since Zubok insists on referring to his subjects throughout as “Zhivago’s children,” but once one adjusts to this questionable idea, it’s impossible not to admire the thoroughness of his narrative. He defines his “children” as coming from three different generations: middle-aged liberals who survived World War II with their ideals more or less intact; people born in the Thirties who got most of their education after the war and derived their ideals from wartime experiences; and a postwar generation of students and young people who were completely post-Stalinist (but still Communist) in their idealism. Zubok alludes in passing to the role of several distinguished members of Pasternak’s generation as well: Anna Akhmatova, Lydia Chukovskaya, Nadezhda Mandelstam, and Dmitry Likhachev, acknowledging their role as carriers of prerevolutionary Russian values, but as with the dissidents, he pays little attention to their influence, a neglect that is doubly surprising since one of his themes is the attempt by Soviet intellectuals to revive some of the traditions of their prerevolutionary predecessors.

Advertisement

That said, Zubok is a reliable and prodigiously well-informed guide to the opinions, attitudes, and changing fortunes of loyal Soviet intellectuals during the approximately twenty years between the early 1950s and 1970s. Among other things he shows how members of all three generations endured a series of shocks after the war and how they repeatedly had to adjust or change their thinking as their hopes for reform rose and sank with each new crisis. The first major shock was the death of Stalin, of course, in 1953, a leader with almost godlike stature in the eyes of older generations, who were almost afraid to confront the future when Stalin’s deep freeze suddenly lifted. Universal fear soon gave way to a cautious cultural liberalization, dubbed “the thaw” after a novel of the same name by Ehrenburg, which was then eclipsed by Khru- shchev’s dramatic secret speech of 1956, in which he enumerated some (but far from all) of Stalin’s crimes and denounced him as a despot. For educated Russians, “a world of certainties came to an end, now that core beliefs and commonly accepted wisdom had turned to dust.”

Khrushchev’s speech turned out to be even more important than Stalin’s physical death, for it announced the death of Stalinist metaphysics. Khrushchev, writes Zubok, had dealt “an irreparable blow to the teleological view of Soviet history” and revived the “‘accursed’ questions” of the nineteenth century: “who was to blame and what was to be done,” and so on. The publication of Pasternak’s novel was one byproduct of the upheaval. Another, according to Zubok, was that Soviet intellectuals—and especially the young—began to turn increasingly to the “universal ideals of justice and human rights” for answers to those questions, thus becoming, in Zubok’s view, “Zhivago’s children.”

Zubok tells his story with a density of detail and complexity of analysis that is truly remarkable. Ranging across the entire spectrum of Soviet cultural life, he carefully plots the rise and fall of magazines, publishing houses, and cultural institutions, together with the changing consciousness of the intellectuals—writers, editors, scholars, government bureaucrats—as they adjusted to ongoing revelations about the past, digested each new crisis, and tried to take advantage of the new freedoms they appeared to promise. Zubok shows how Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization led to a cautious opening to the West, encouraging the intellectuals to begin looking abroad for wider horizons. He also explains how the regime was always uneasy about these efforts if not hostile to them, and shows how the complex interplay between Soviet foreign and domestic policy created not only opportunities but also unexpected setbacks.

The first and most serious setback came with the crushing of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, which brought particularly bad news for intellectuals. The KGB reported that the rebellion had been sparked in part by subversive literary discussions in the Petöfi Circle Club for writers and intellectuals in Budapest, and the implications were clear: lift the lid on intellectual life and you’ll get a counterrevolution. The resulting surge in Soviet nationalism threw a pall on the very idea of more cultural freedoms, and liberalization was temporarily halted. But this backlash was followed by a hugely successful World Youth Festival in Moscow in the summer of 1957, and the launching of the Sputnik satellite in the fall of that year.

The publication of Doctor Zhivago in December was a double-edged sword: the fact that it happened—and Pasternak survived—was an encouraging sign, but its publication also led to an outburst of official anti-Western propaganda that almost canceled its benefits. The festival seemed to indicate that controlled cultural exchanges with the West were a good idea after all, and the success of Sputnik emboldened Khrushchev to declare that the Soviet Union had completed “the full and final construction of socialism.”

It was an empty boast, of course, but however capricious and erratic, Khrushchev’s policy of making overtures to the West linked the Soviet Union to the outside world more closely than at any time since the early Thirties, and Zubok astutely argues that the subterranean changes that occurred inside Soviet society can be connected to parallel cultural trends on the other side of the no longer quite iron curtain as well. In his desire to emphasize these similarities and explain Soviet society to Western readers, Zubok plays a bit too fast and loose with terms like “new deal” to characterize Khrushchev’s decision to supply more consumer goods, “new journalism” to describe Izvestia ‘s cautious investigative articles, “new wave” for the arrival on the literary scene of poets like Yevtushenko and Voznesensky, and especially “baby boomers” for the younger Soviet generation.

Advertisement

Still, he makes some valid comparisons between the young radicals of 1968 in both the East and the West, and judges the social and political upheavals of that era to have common roots in political stasis and frustrated idealism. His argument is generally convincing, though he passes over the irony that young Western radicals were promoting many “socialist” ideas that were being discredited in the East (though not so much by Zubok’s “Zhivago’s children”).

Zubok is the author or coauthor of several books on the cold war. He writes about his present subject with both academic rigor and the informed sympathy of a former insider, and he charts the progress of his “children” with a wealth of illustration, drawing on the memoirs, diaries, and published reminiscences of many of the leading writers and other cultural figures, as well as making excellent use of the newly opened archives of the Writers’ Union and other official bodies, not to speak of the vast literature that has grown up around this subject. His book is scholarly but also highly readable and accessible, and is rich in anecdotal material that enlivens the sociological analysis.

Among other things, he gives an excellent account of the importance of science to Soviet intellectuals after the successes of the Soviet nuclear and space programs, emphasizing the “free spirit” to be found among research scientists in their formerly sealed scientific institutes and the way that progressive scientists such as Andrei Sakharov interacted with literary and other artists. He dutifully records the rise to rock star fame and fortune of Yevgeny Yevtushenko, Bella Akhmadulina, and Andrei Voznesensky (who specialized in importing physics imagery into his lyrics), along with the singer-songwriter Bulat Okudzhava and others who explored the limits of the permissible. He notes how the poets began gathering informally by the statue of Mayakovsky (fittingly nicknamed mayak, or lighthouse) in downtown Moscow—in a pale imitation of Mayakovsky’s own public readings before and during the Revolution—and joined forces with young artists to put out unofficial pamphlets and journals, while the artists, impatient with socialist realism, started exhibiting experimental work at scientific institutes. And as he points out, it was an exhibition of painting and sculpture by nonconformist artists in December 1962 that set off the next explosion and blowback in Soviet culture.

The art itself, like most of the (by Soviet standards) avant-garde poetry and prose of the time, was mildly experimental and largely derivative, but it was far too advanced for Khrushchev, who went berserk when he saw it, characterizing the artists as “pederasts” and their work as “dog shit.” That Khrushchev went to an art exhibition in the first place was, as Zukov explains, a set-up by the KGB, which was increasingly involved in damage control after Khrushchev’s reckless moves in the cultural sphere (he had just authorized publication of Solzhenitsyn’s A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich) and foreign policy (he had recently been forced to back down over missiles in Cuba). Khrushchev called a large gathering of the cultural elite at the Kremlin to discuss the state of the arts in the Soviet Union, and after a long vulgar harangue bellowed: “The Thaw is over! This is not even a light morning frost. For you and your likes it will be the arctic frost.”

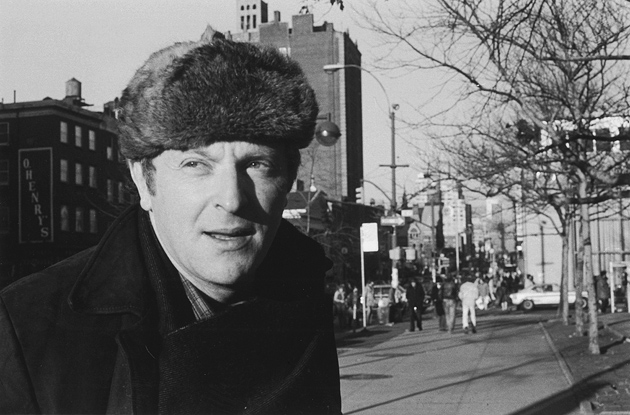

In Leningrad, the phenomenally gifted Joseph Brodsky was arrested on charges of “parasitism” and sentenced to five years’ exile and hard labor. In Moscow, gatherings at the mayak were prohibited, visual artists retired to the privacy of their unofficial studios, and Solzhenitsyn, the party’s darling for a while, was turned down for the Lenin Prize and ultimately silenced. Soon, Khrushchev, too, caught frostbite and in 1964 was replaced by the ultimate apparatchik, Leonid Brezhnev, who soon ordered the arrest of two little-known writers, Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel, for publishing their work abroad under pseudonyms.

Sinyavsky and Daniel had been two of the pallbearers at Pasternak’s funeral, and their decision to follow his example—consciously and boldly, rather than by semiaccident—gave birth indirectly to the dissident movement. On “Constitution Day,” December 5, 1965, not long after the disappearance of the two writers into the Lubyanka, about fifty people gathered in Pushkin Square in Moscow, ostensibly to mark the holiday but in reality to protest the arrests. Though modest, the demonstration was unprecedented in postwar Soviet history, and the unofficial organizers were clever enough not to challenge the Soviet authorities outright. They outflanked them by unfurling banners calling on the government to respect its own laws and constitution (which in theory—and on paper—guaranteed civil rights) and conduct an open trial.

It was a brilliant move, notwithstanding its costs. The KGB confiscated the banners, arrested half the demonstrators, and arranged for Sinyavsky and Daniel to get prison terms of seven and five years respectively on charges of “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda,” a catch-all indictment that mocked the very idea of legality. But the trial, even though rigged, was opened to the public, allowing representatives of the Western press to attend, and draw international attention to the issue of civil and human rights in the Soviet Union.

An unofficial transcript of the trial was smuggled abroad and broadcast back to Russia by Western radio stations, and Alexander Ginzburg (with the help of Yuri Galanskov) compiled a White Book of documents about it that was circulated in samizdat, a form of self-publishing that Ginzburg and Galanskov had helped to invent five years earlier with their unofficial magazines Syntax and Phoenix. The White Book inevitably made its way abroad, leading to a trial of its compilers and a new samizdat book, The Trial of the Four, starting a deadly whirligig of more protests, more samizdat, more arrests, and a steadily growing opposition to censorship and arbitrary imprisonment that eventually spawned the hugely influential human rights journal The Chronicle of Current Events. Samizdat was followed by tamizdat—publication abroad—and the burgeoning dissident movement entered into its long, punishing, and deadly struggle with the authorities.

Zubok finds room for an outline of these developments, but keeps his focus fixed on efforts for reform within the establishment, which became increasingly feeble and led to a depressing denouement. Jolted by the setback of the trial of Sinyavsky and Daniel and its consequences, loyalist writers, though deeply sympathetic and supportive to begin with, allowed themselves to be edged to the sidelines by Brezhnev’s creeping re-Stalinization, and they were virtually silenced when Soviet troops invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968, crushing hopes raised (in the Soviet Union as well as Czechoslovakia) by the Prague Spring.

Zubok describes the helpless Yevtushenko as shedding “the tears of a deceived idealist” over this disaster, while Aksyonov “drowned his rage in alcohol.” True, the loyalists still attempted to remonstrate with the authorities behind the scenes, but the only public demonstration against the Soviet invasion attracted exactly seven people—all dissidents—and they were either jailed or sent into exile. “The hopes and illusions of Zhivago’s children had come face to face with a brutal reality check,” writes Zubok. “The myth of a socially engaged and morally potent intelligentsia collapsed in August 1968, smashed by the brutal force of the authoritarian state.”

Zubok’s central story comes to a virtual end with this dramatic declaration. His last chapter, “The Long Decline,” forsakes the detailed narrative of his first three hundred pages to cover the next twenty years in thirty-seven pages, in which he briefly describes the disillusionment of the elder “children,” the cynicism of their younger brethren, and the general passivity of the Soviet intellectuals in the face of Brezhnev’s reactionary policies. In his epilogue he briefly chronicles Gorbachev’s last-ditch effort to save the system with his “golden age of glasnost,” and then comes up with another surprise. Not only did “Zhivago’s children” let Gorbachev down by not responding gratefully to his efforts, but they were also responsible for the collapse of the Soviet empire. In Zubok’s reading, the intellectuals grew so intoxicated with their newfound freedoms that they turned against Gorbachev’s unprecedentedly liberal regime and destroyed it by accusing it of stopping short of abolition of Party control:

Nobody realized that this was the last time that the intelligentsia…would play a central role in Russian history…. The squabbling chattering classes…dug the grave not only of Soviet communism, but also of the Soviet state.

It’s a staggering leap from the preceding narrative to this conclusion, which seems to reflect Zubok’s nostalgia for a Soviet system on the brink of becoming workable and his corresponding disappointment over its failure, and it strikes me as doubly flawed. As Zubok himself makes clear, the generations of intellectuals who came after Pasternak knew very little about life before or without communism, and although they imagined themselves recreating the old traditions of the Russian intelligentsia, they “remained by and large Soviet, and in many instances communist” in their thinking. They opposed “Stalinist dogmas and lies,” yet based themselves on “the values of the Revolution and socialism.” Zubok adds that “a great number of them, perhaps the majority, had no clear understanding of Western notions of freedom, democracy, and the rule of law” (notions that certainly inspired the dissidents) or interest in prerevolutionary forms of government. What they aspired to was to act as enlightened cultural umpires and to encourage freedom of expression and debate within the assumptions of Marxism, without threatening the state in any way.

In other words, the loyal intellectuals operated within a sort of cage. Sometimes the bars were widened or bent a bit, and sometimes the inmates were let out to play, but the Soviet government always kept the key in its pocket. So what was the nature of the “intellectual, spiritual and moral” authority that Zubok accuses them of squandering by not supporting Gorbachev, and how can they be held responsible for bringing down the state when they never held any real power?

The fact is that by Zubok’s own lights, the Soviet intellectuals weren’t Zhivago’s (still less Pasternak’s) true children at all. They were distant relations, perhaps, with some family resemblances, cousins or second cousins, who recognized Pasternak’s qualities and admired his virtues without fully understanding them, let alone being able to emulate them. The truer children—in both the ethical and literary sense—were the dissidents such as Brodsky and Sinyavsky, and Zubok actually suggests this in his last chapter, observing that many of the dissidents undoubtedly did think of themselves as the heirs of the prerevolutionary intelligentsia, as did many others inside and outside the Soviet Union. But having raised the thought, he simply leaves it there, neither agreeing nor disagreeing with it, though by virtually ignoring the dissidents in his analysis, he indicates that he disagrees with such a view.

The second problem lies with Zubok’s grand contention that the death of the Soviet intelligentsia marks the death of the Russian intelligentsia as a whole. In support of this idea he cites Czes aw Mi osz to the effect that the depth of Russian literature was “bought at too high a price,” and adds, “one may suspect that Russia needed its critical intelligentsia and its high culture only as long as it suffered from tyranny, misery, and backwardness.” It’s hardly a new idea (especially as expressed by a Central European), but although the unique intensity of Russian writers might owe something to social pressures, these hardly explain, for example, the brilliance of the modernist movement in Russia, starting with Alexander Blok and Andrei Bely, and continuing with the generation of Mandelstam, Pasternak, and Akhmatova, to name only a few. In fact the true sources of Russian creativity are impossible to isolate, but they would seem to lie much closer to Russia’s religious and philosophical traditions than to a hostile political environment.

Zubok suggests that he is disillusioned with a post-Soviet Russia that has embraced market capitalism and mass culture, and that like the West now treats art as “a commodity,” literature and cinema as “a form of entertainment,” and “high culture” as “elitist.” It’s a familiar leftist complaint, which rests on the fallacy that high culture was ever anything but elitist (my dictionary, incidentally, defines intelligentsia as “intellectuals who form an artistic, political, or social vanguard or elite”), and it does less than justice to the arts both in Russia and in the West.

But perhaps Zubok should take heart. Russia’s present government, with a nudge from old KGB hands, is well on the way to a restoration of the old repressive norms, and may well reproduce the conditions he apparently regards as necessary for an intelligentsia to thrive. No doubt he would resent such an implication; but it’s absurd to imagine a future Russia without its eminent writers, artists, and intellectuals, whatever they call themselves. Zubok has done a fine job of characterizing a slice of Russian intellectual life over a couple of turbulent decades of Soviet history, but his claims to a larger significance for the loyalist writers and others he studies strike me as misleading and overblown. The unfortunate effect is to seriously skew the message of an otherwise intelligent and engrossing book.

This Issue

January 14, 2010