Following Boyhood (1997) and Youth (2002), Summertime concludes J.M. Coetzee’s autobiographical trilogy. It is a teasing and surprisingly funny book, at once as elaborately elusive and determinedly confessional as ever autobiography could be. If Boyhood and Youth were remarkable for Coetzee’s use of the third person (the author declining to identify with his younger self) and the present tense (a narrative device more commonly associated with fiction than memoir), Summertime takes both distancing and novelizing a step further. Despite our seeing Coetzee’s name on the cover and hence assuming the author alive and well, we are soon asked to believe that he is now dead, the book being made up of five interviews conducted by an anonymous biographer who is speaking to people he presumes were important to the writer during the years 1972–1975.

Coetzee’s reflections on his younger self are thus articulated through his imaginings of what people might remember of him and choose to disclose to an unauthorized biographer who is increasingly anxious that the material he is gathering will disappoint. It is at once clear that any attempt to establish the truth status of Summertime, or indeed the trilogy as a whole, is unlikely to yield satisfying results.

Two of the three books bear the subtitle “Scenes from Provincial Life,” suggesting an attempt to shift the focus away from biography and to remind us that “no man is an island, entire unto himself”; each of us must be understood in relation to those we live among. The irony here is that in Youth the young Coetzee is determined to prove “that each man is an island” (my emphasis), while in Summertime an ex-lover remembers Coetzee as having an “autistic quality,” not “constructed to fit into or be fitted into. Like a sphere. Like a glass ball. There was no way to connect with him.” If personality is to be understood through one’s negotiations with others, the burden of this trilogy is that for Coetzee such negotiations have always been arduous.

Boyhood tells of a child trying to find a position he can be comfortable with, first inside a family, then in a larger community. But in the South Africa of the 1940s, in a family of Afrikaans origin that has chosen to speak English, in a stridently Christian community where his parents are agnostic, with a father who never hits his children but allows a black servant boy to be whipped, this is far from easy. The young John wants his mother to be always “in the house, waiting for him when he comes home” but at the same time resents her possessive love and is secretive in response. He does not speak about his problems with violence, his revulsion—whether it be the castration of farm animals, canings at school, or the whipping of black boys—yet fascination with it.

It is over the issue of violence that John first feels isolated. Other boys in the class have been caned; he has not. He fears the cane, the humiliation of punishment, but feels he must undergo this initiation to take his place in the world. However, initiation is understood as a test that might expose his inadequacy. John behaves scrupulously to avoid arousing his teachers’ ire and works hard to be top of the class, hoping that this achievement will substitute for initiation, though in fact it only emphasizes his isolation.

The question of religion provides another comedy of positioning. Leaving Cape Town for provincial Worcester, on arrival at his new school John is asked whether he is Christian, Catholic, or Jewish. Since his family is “nothing,” he says Catholic at random, unaware that as a consequence he will be excluded from the morning assemblies of the Christian majority, mocked as Jewish by other boys, and harassed by the school’s few real Catholics who realize at once that he has never been to catechism. The predicament would be hilarious if the boy didn’t suffer so much. He now wishes to declare himself Christian and join the majority, but fears that if he does so his shameful ignorance will be exposed and he will be “disgraced.” “Disgrace” is an important word for Coetzee: it marks the point where a test is failed, shame is made public, and the guilty party ostracized.

In a world divided into blacks and whites, Afrikaans and English, Christians and Jews, the boy tries to line up the various sides and decide where he stands. The Afrikaans are surly and violent, the English gentlemanly and nonviolent, except that then it is a nice English friend of his father’s who whips the black boy. Confused, John looks to his mother for guidance but “she says so many different things at different times that he does not know what she really thinks.” Exasperated, he nevertheless sympathizes with his mother when his father’s relatives are less than warm to her on their huge farm in the Karoo. However, this Afrikaans farm is the only place where John feels at home:

Advertisement

The secret and sacred word that binds him to the farm is belong…: I belong on the farm. What he really believes but does not utter, what he keeps to himself for fear that the spell will end, is a different form of the word: I belong to the farm.

It is a fatal attraction, for, as John will later appreciate, the farm, the Karoo, Africa itself does not belong to him or his forebears. It was stolen. There is no honorable place for John in the Karoo he loves.

Boyhood ends with the disgrace of John’s father. Expelled from legal practice for shady dealings, he lies on his bed tossing cigarette stubs into the urine in his chamber pot while his wife works all hours to save the family from ruin. John cannot bear the thought that his mother’s self-sacrifice will demand a lifetime’s gratitude in return. Yet he fears her judgment of his mean-spiritedness. “He would rather be blind and deaf than know what she thinks of him. He would rather live like a tortoise inside its shell.” It is the closest the boy gets to imagining a position for himself.

Youth picks up the story as Coetzee, in his late teens, seeks an escape from his dilemmas in literature: “For he will be an artist, that has long been settled.” Yet at Cape Town University he is studying mathematics and in London he will work as a computer programmer, hiding his vocation for fear of being exposed as a fool. While in Boyhood John looked for his place among religions and ethnic groupings, now he measures himself against great minds past and present. Rousseau and Plato would approve of his simple diet. Pound and Eliot warn him to be ready to suffer; Picasso and Henry Miller invite him to initiation through passion. Sexual passion is a sign of election in an artist. So John allows himself to be seduced by the neurotic, older Jacqueline, who moves in with him and makes his life miserable for six months. Again, and always with Coetzee’s characteristic precision and restraint, the book allows comedy and misery to vibrate together, never quite inviting us to laugh or weep out loud, but constantly forcing the smile on the wince, the wince on the smile.

There have been other memoirs written in the third person. In The Education of Henry Adams (1907) the author passes disparaging remarks about himself with polished irony, preempting more aggressive biographers while eliding uncomfortable sections of his private life, in particular his marriage and his wife’s suicide. Thomas Hardy wrote a guarded autobiography in the third person and arranged for its posthumous publication under his second wife’s name. Anxious about exposure of any kind, Hardy destroyed the letters and notebooks he worked from, forcing biographers to use his own version of his life as their principal source.

But while Coetzee has always been an extremely private man and his trilogy offers only a very incomplete account of his life, it would be hard to claim that he is guarding against exposure. Unflinchingly, he describes a younger self whose inadequacy when faced with a girlfriend’s unwanted pregnancy, or the bloody sheets of a lost virginity, or simply a stranger’s generosity comes across as cowardly and caddish. Perhaps, having worried constantly in his youth about being shamed, the older Coetzee is determined to be so “ruthlessly honest” that no future biographer can outdo him. Alternatively, one might say that in the absence of the corporal punishment he still feels he deserves, he is obliged to run the whole show on his own—transgression, trial, judgment, and punishment—the third person he uses suggesting the divided self that such a solipsistic project entails.

Where Youth differs from Boyhood is in its obsessive use of questions, the young man’s thinking being made up of one uncertainty after another. So when Jacqueline makes a scene after discovering what John has written about her in his diary, we read:

If he is to censor himself from expressing ignoble emotions—resentment at having his flat invaded, or shame at his own failures as a lover—how will those emotions ever be transfigured and turned into poetry? And if poetry is not to be the agency of his transfiguration from ignoble to noble, why bother with poetry at all? Besides, who is to say that the feelings he writes in his diary are his true feelings? Who is to say that at each moment while the pen moves he is truly himself? At one moment he might truly be himself, at another he might simply be making things up. How can he know for sure? Why should he even want to know for sure?

Having no clear position in the world goes together with an uncertainty about who one is. In Summertime one ex-lover will pronounce John such a “radically incomplete man” that it was impossible to fall in love with him. Yet toward the end of Youth there is a growing sense that precisely this incompleteness, his failure to become a South African, or a Londoner, or a passionate lover, his feeling that he hasn’t really lived, will be his subject.

Advertisement

In the British Museum he discovers the chronicles of early travelers in South Africa. Aware that this is “the country of his heart…he is reading about,” John is “dizzied” by the realization that these men “really lived, their travels were real travels,” and it occurs to him that he might, in prose, construct a tale that, though fiction, would have the same “aura of truth” as these old travel books. It will be the “purely literary” project of one who didn’t experience these things but whose concentration is such that the account will seem more “alive” than that of men who were there. This achievement will enable him to “lodge” his book in this “library that defines all libraries.” Unable to find a home or to place himself in an intense relationship, Coetzee will be a lodger in the house of literature, writing fiction that seems truer than truth.

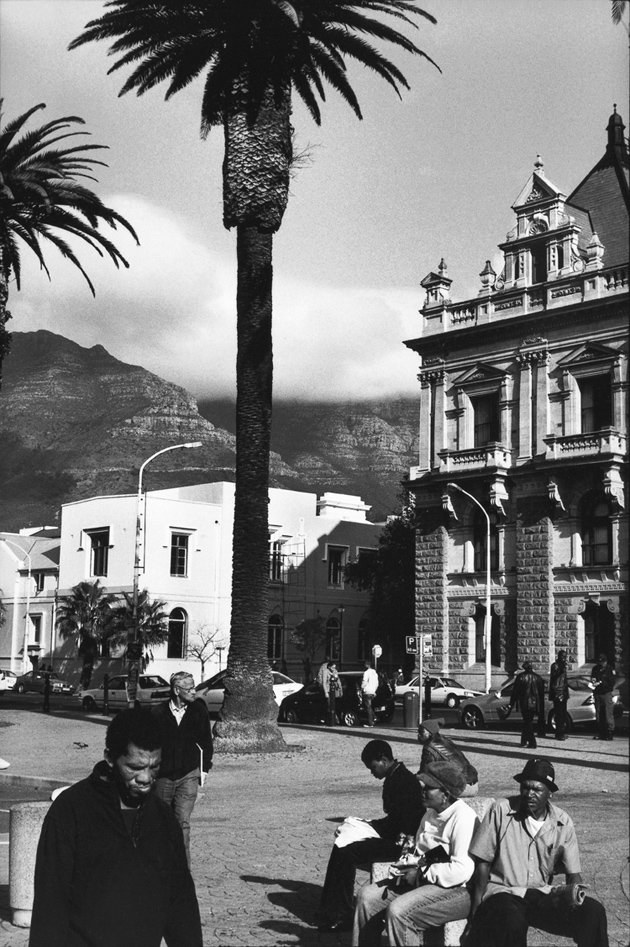

“How to escape the filth?” Summertime opens with a would-be biographer reading from Coetzee’s notebooks of 1972–1975 to a woman who was his lover at the time. The “filth” is the South African government’s brutal repression of the anti-apartheid movement as reported in the newspapers and denied by the politicians. Refused residency in the United States, John, aged thirty-two, is back in Cape Town and living with his widowed, apathetic father. Once again, positioning is important. Less than a mile from their gloomy home with its rotting mudbrick foundations is Pollsmoor Prison, “the South African gulag.” Most of the middle-class community lives in denial, but John feels shame and frustration. In indirect response, he labors at putting a “concrete apron” of ninety-six square meters around the crumbling house, doing “what people like him should have been doing ever since 1652, namely, his own dirty work”—as if this refusal to resort to black labor could make up for the shame of apartheid and earn John an honorable place in South Africa. What does Julia, the ex-lover, think about all this? the biographer asks.

There follows a sixty-five-page interview in which Julia, now a psychotherapist in Canada, speaks as much about herself as about Coetzee. John, she says, was actually “a minor character” in a drama played out between herself and her husband. While the latter was traveling, the lovers enjoyed an “erotic entanglement” in the marital bed. Yet John was peripheral to her life; at the one moment when she was ready to leave her husband and he could have become a major player, he “took fright” and snuck out of the motel where she was sleeping.

Julia—or rather, of course, Coetzee who is writing Julia’s part—puts this behavior in relation to his fiction. Dusklands, she says of the novel published during their affair, is largely about cruelty, but the source of that cruelty “seems to me [to lie] within the author himself.” Not that Coetzee was cruel to her. On the contrary, “his life project was to be gentle.” He had “announced to me he was becoming a vegetarian…. He had decided he was going to block cruel and violent impulses in every arena of his life…and channel them into his writing.” As a result, John was “the only man I knew who would let me beat him in an honest argument…. And I always beat him,” since “pragmatism always beats principles…. Principles are the stuff of comedy. Comedy is what you get when principles bump into reality.”

Certainly there’s comedy to be had in the description of this willfully unassertive man partnering a woman who sees sex “as a contest, a variety of wrestling in which you do your best to subject your opponent to your erotic will.” “He was not in my league,” Julia complains. When John tries to persuade her to moderate her lovemaking to fit the slow movement of a Schubert string quintet, the better to “re-experience” the sexual feelings of a bygone age, Julia shows him the door. “The man who mistook his mistress for a violin,” she comments.

The humor intensifies in the next interview. This time the biographer has already written up the taped transcript as a colorful narrative and is reading it back to Coetzee’s cousin, Margot, who frequently objects that “your version doesn’t sound like what I told you.” So we are constantly reminded that Summertime is a most indirect account of the author’s life, Coetzee taking the same resourcefully guarded approach to the reader that his novelized self assumes in his relationships.

Margot tells how John brought his father to the family farm for Christmas, spending much of his time repairing his pick-up because he was determined not to resort to black labor. As a result the vehicle breaks down while the two cousins are driving across the desolate Karoo and they are forced to spend a shivering night leaning against each other across the gearstick. John, “whose body manages to be both scrawny and soft at the same time”—not a good fit for Margot—withdraws at once into twitching sleep while Margot berates him as a “failed runaway, failed car mechanic too, for whose failure she is at this moment having to suffer.”

John’s enemy on the farm is another cousin, Carol, who feels that John is “affected and supercilious.” Married to a successful German engineer and planning to escape to the States before South Africa collapses, Carol is a “hard” woman who is nevertheless “soft” when it comes to the suffering around her. “She is the one who…blocks her ears when the slaughter-lamb bleats in fear.” In short, Carol, like the middle-class whites around Pollsmoor Prison, lives in denial. In his wry, roundabout fashion, Coetzee is giving us clues here to the political side to his work. When Margot asks John if he remembers how as a boy he once pulled the leg off a locust, he tells her: “I remember it every day of my life…. Every day I ask the poor thing’s forgiveness.” Later, when Margot can’t see the point of his studying the now dead Hottentot language—who can he speak to in Hottentot?—John replies: “The dead…who otherwise are cast out into everlasting silence.”

Uneasy about his position in a violent world, experiencing every forceful action of his own as crime, Coetzee steps aside and in an expiatory gesture writes against the denial of the majority who are at ease, giving voice to the suffering that people like Carol are determined to shut out. Coetzee’s insistence on evoking the world’s unloveliness is part of this assault on the deniers, while his constant reminders that his text is made up prevents us from rushing to verify it or disprove it—he will no more confront us than he will Carol. Rather we are forced back on our own experience to decide what truth there is here.

One sufferer unlikely to have had her story told if she hadn’t crossed Coetzee’s path is the subject of the third interview. Adriana, a Brazilian dancer, had gone to Angola with her husband in the 1960s. Expelled, they came to Cape Town where the husband was brutally assaulted. While he languishes in a coma, Adriana teaches dancing and raises her two daughters, paying for the youngest to take extra English lessons. But hearing that the teacher has an Afrikaans name, she fears he is not a native speaker. Worse still, the teenage Maria Regina has a crush on him. “Mr. Coetzee is not an Afrikaaner,” the girl protests. “He has a beard. He writes poetry.” Indeed! Determined to investigate, Adriana invites Coetzee to their house.

What follows is high comedy. Coetzee tries to explain his Platonic “philosophy of teaching” to this no-nonsense mother. “What a strange, vain man,” she thinks. And weak. And frightened. And ignorant. He invites the family to a hopelessly organized picnic. Convinced he is after her daughter, Adriana withdraws the girl from his classes, only to find Coetzee writing love letters (about Schubert!) to her and embarrassing her by attending her dance classes. In Youth the young Coetzee had seen “no reason why people need to dance.” Now his incompetence provokes Adriana’s contempt. “The Wooden Man ” she dubs him. “Disembodied.” “He could not dance to save his life.” Nowhere else does Coetzee have so much fun at his own expense, while simultaneously pushing toward the core of his uneasiness: he is not even at home in his own body.

The remaining two interviews, with university colleagues, confirm the bundle of character traits that over the trilogy we have been persuaded to recognize as Coetzee’s. Nobody who actually knew him, the author would have us believe, found him convincing. “He had no feeling for black South Africans,” Professor Sophie Denoël, a colleague and ex-lover, reflects; he romanticized them as “guardians of the truer, deeper, more primitive being of humankind.” It was “politically unhelpful.” Then Summertime ends as it opened with fragments from Coetzee’s notebooks. His father has cancer of the larynx and undergoes an operation. John realizes he is being called on to nurse a dying man. The book’s closing words are:

He is going to have to abandon some of his personal projects and be a nurse. Alternatively…he must announce to his father: I cannot face the prospect of ministering to you day and night. I am going to abandon you. Goodbye. One or the other: there is no third way.

It is the last of a long series of tests. How John fared we do not know.

Nor is it clear how the reader is to respond to the fact—available for all to read on www.nobelprize.org—that in 1972 J.M. Coetzee was married with two children. Presumably his family remained in the United States when he returned to South Africa. That he might never have mentioned this to lovers and friends is possible; that they, at the time of these interviews, would not have commented on the fact seems unlikely. So is Summertime an autobiographical novel that simply elides one part of Coetzee’s life but is otherwise more or less accurate? Or does it excite the prospect of biography only to offer something mostly fictional? Or is the omission of the author’s marriage and children at once the most discreet statement of his uneasiness and the loudest proclamation that we must leave aside categories and genres and make of the book what we will?

Whatever the case, Summertime’s shifty position between biography and fiction becomes a powerful analogy for Coetzee’s difficulties positioning himself in the world; it is as we struggle to get to grips with its mixture of disclosure and secretiveness that we come closest to him. And precisely as we fail to pin him down, we feel sure that this trilogy has earned its place at the heart of contemporary literature.

This Issue

February 11, 2010