The Art Student’s War, Brad Leithauser’s new novel, is a loving, elegiac caress of a city used to rougher treatment: Detroit, where he grew up. But this is not the already rusting city that Leithauser knew as a child; it is his parents’ Detroit, active, essential, and alive, its factories going twenty-four hours a day, turning out the tanks and jeeps needed by America’s boys overseas.

This is Leithauser’s seventh novel. He is also the author of five collections of poetry. Leithauser’s literary curiosity and skill allow him to roam freely across borders of poetry and prose. But even within the landscape of the novel, this playful, erudite, and emotional writer travels lightly and far and never in quite the direction one would have predicted. A Few Corrections (2001), for example, his novel about a son trying to understand his late father, is a touching, exuberant, multigenerational epic masquerading as a tight, short volume, neatly arranged around corrections to an obituary. The Friends of Freeland (1997), on the other hand, is a darkly comic, sprawling invention, a scathing satire of a place that does not exist—the windy, wintry northern isle of Freeland, complete with its ancient sagas and modern culture wars.

And then there is Darlington’s Fall (2002). It was another poet, Randall Jarrell (who also wrote a novel, the exquisite, unerring comedy of academic manners Pictures from an Institution), who famously said that a novel is a prose narrative of some length that has something wrong with it. (Jarrell’s novel, perhaps the funniest book I have ever read, had no plot.) With Darlington’s Fall, Leithauser has proved Jarrell partly wrong, for his novel is written entirely in verse. And verse or no verse, a novel it surely is. The story of Russell Darlington, a boy who grows up to be a passionate and eminent entomologist, Darlington’s Fall is so beautiful and so suspenseful that the reader is breathless both with the headlong narrative excitement of a novel and, simultaneously, with poetry’s call to stop—to repeat, reread, recite.

None of these vigorously composed novels would have predicted the next, and none, certainly, would have predicted The Art Student’s War. Throughout the books, however, runs a persistent, underlying, unobtrusive, and beautifully balanced formality. And Leithauser’s own sense of these works as a continuum is clear: each book contains, as an epigraph, a quotation from his own previous novel. Finally, there is Leithauser’s preoccupation and fascination with the past—how it lives and how it dies—which shows up, as real as any character, in his rain forests, arctic snows, and midwestern suburbs. The Art Student’s War, though utterly different in timbre, rhythm, and key from his earlier prose, is no exception.

Coming from such a fiercely eloquent writer, one who can construct a cold and scruffy nation out of ice water or deconstruct a slick and reckless life from an inaccurate obituary paragraph, one whose rich, energetic prose and poetry can veer from fearless satire to the precise glory of a butterfly’s wing to the enormous, romantic relief of love, The Art Student’s War is surprisingly soft and filtered, like an old postcard.

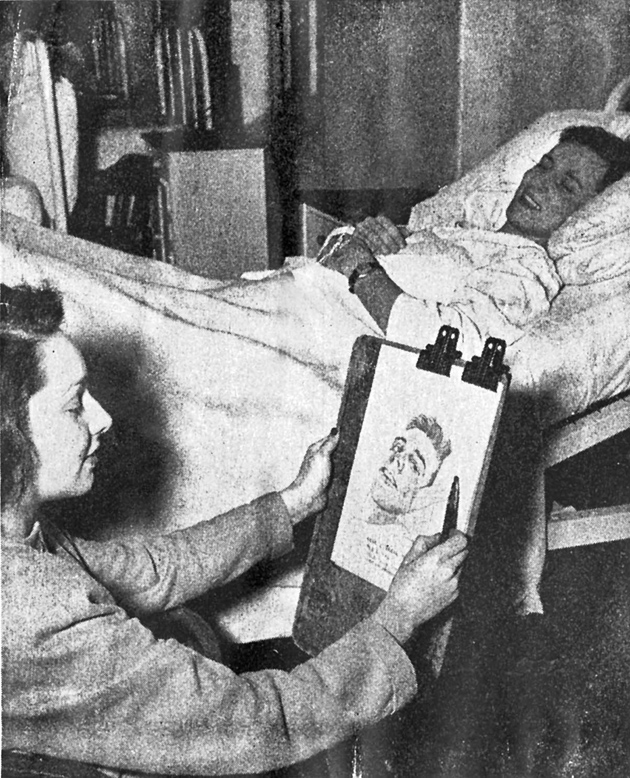

We meet the eighteen-year-old heroine on a streetcar in an opening scene that is also like an old postcard, a tableau tinted with color: “A tall girl wearing a red hat…. The olive drab and navy blue of the boys’ uniforms have reconstituted the palette of the city.” The girl, so aware of color, is named Bianca, that pure absence of color that is really a reflection of all the colors of the visible light spectrum. Her last name is Paradiso, and Leithauser’s novel openly, warmly honors a world less self-consciously polluted than our own. In an author’s note, he explains that the novel was inspired by his mother-in-law, who drew portraits of hospitalized soldiers, some of which, bold and disarming, appear scattered through the book. A photograph of his mother-in-law is also included: “artist, bed-ridden soldier, and the portrait that binds them. It’s a small image that seemed to summon me to write a large and grateful book.”

The Art Student’s War is imbued with that feeling of gratitude, as well as a potent nostalgia not just for a time and place, but for a state of mind that, like Freeland, one suspects, never really existed. In this “tribute—to my mother-in-law, and to my parents, whose Midwest I would seek to capture, and not least to Detroit itself, my beleaguered and beloved hometown, in all its clanking, gorgeous heyday,” Leithauser is in search of nothing less than purity. If the attempt sometimes feels a little gauzy or mild, the generosity of the whole enterprise more than makes up for it.

Advertisement

Bea, as Bianca is called, is an art student, determined to embody her professor’s remark that a true artist observes everything. On a crowded streetcar, she stands busily, dutifully, and somewhat dreamily trying to observe, when a young wounded soldier on crutches climbs aboard:

And then—then, to the girl’s horror, to her crawling, incredulous, consummate horror—the soldier signals to her. She prays she’s mistaken, but there it is, undeniably: the soldier repeats the gesture and lifts a beckoning eyebrow….

Everybody’s watching. It’s just as though the streetcar has halted. It’s as if the whole city has halted and everybody in Detroit is gaping at her, while she, so keenly susceptible to embarrassment, undergoes paralysis.

It is an unimportant moment, really —a man rises to offer the soldier his seat, and the polite soldier offers the seat to a pretty girl. Just a confluence of small gestures, which an impressionable teenager experiences as a rushing, Romantic cataract of meaning; and the prose here, Bea’s prose, is eager, almost gushing.

The language is far different from the astringent irony of some of Leithauser’s earlier characters. Eggert, for example, the self-described rat-like narrator of The Friends of Freeland, observes everything, too—everything dark and weak and scabby and raw. His description of sex? “It was meant to leave you, at its best, with the winded feeling of accomplishment savored by a man who has just squeezed himself and his baggage onto a crowded subway train.” His friend Hannibal’s most intimate endearments? “You’re my bristly old sow’s belly…. My very own fly-dotted sheep’s dropping. Fish stink and rat’s plunder.” Eggert is a writer, a cultural reactionary compulsively pumping out books about Freeland’s ancient sagas and language, trying to hold back the tide of American junk.

The wild, reckless richness of Leithauser’s Freeland vocabulary is invigorating. But far from being amused by such rank wordplay, Bea Paradiso would be appalled, if she could even grasp its meaning. She is far too innocent. Yet The Friends of Freeland is also about innocence, a knowing, sly, and desperately clawing reach for a world that is gone; an angry insistence on an imaginary world that feels more real than the one stretched out ahead.

The idea of a “vanished world” is central to A Few Corrections as well. Leithauser sends his narrator to the town of Restoration, Michigan, to try to understand what his father experienced there. In this case, the medium Leithauser uses to outline the vanished world is not brilliantly cranky linguistic excess, but emptiness:

I’m wandering the streets of Restoration and something is missing—where are the people? It’s as if I’ve stepped onto a movie set when everyone’s on lunch break. Where are the people?—where’s the life? Long blocks of dilapidated houses, boarded-up storefronts, weedy parking lots, and the few straggling souls I do encounter might have been put here expressly to illustrate just how moribund the town’s become. A drunk fishing with a stick through a trash can. An aged orange-haired woman with a cotton ball in her ear, marching out of the post office and shaking her head combatively at a fire hydrant. A couple of ashen men…so weathered it takes you a moment to recognize they’re identical twins. A shirtless, towheaded, obese young man wheeling a pair of shirtless, towheaded, obese babies in a stroller that isn’t a stroller but a supermarket cart.

Bianca, trying so hard to notice everything, would not have seen a cotton ball pressed into a woman’s ear, and if she had, she would not have thought it worthy of mention. She is young and patriotic, untouched by cynicism; untouched, even, by life. Leithauser presents her as an eager blank slate, and she doesn’t so much see a vanished world as embody it. With Bianca Paradiso, Leithauser has envisioned his vanished world through a kind of mimicry, through a glass, the glass of a faraway girl:

The ghastly moment unfreezes itself, there is no way out except forward, and, stooping (she’s quite a tall girl, who tends to stoop accommodatingly), Bea slips into the empty seat. She plants her gaze on the gritty floor, where a couple of last-drag smokers have, on boarding, pitched cigarette butts. The true painter observes everything, and yet she cannot bear to meet anyone’s eyes. She vows not to look up again—not once—until her stop is reached.

It is one of the unsettling qualities of this novel that Bea’s old-fashioned, girlish diction sometimes feels less like Bea’s words in 1946 than the words of an eighteen-year-old in a 1946 novel. This is not a question of authenticity; it is a question of distance, the distance of time. Leithauser wants us to know Bea, to accompany her as she travels through the grandness of wartime Detroit; he wants to peer through the veil of history. At the same time, he uses that veiled distance to keep Bea shrouded, almost as if he were protecting her and the world she represents.

Advertisement

Leithauser has written a novel that is not only nostalgic for a previous generation’s world, but is also about nostalgia, the way it comes to us in drawings, photographs, family memories: the way the living experience the dead. In Darlington’s Fall, he wrote:

(The dead are realer than the living, insofar

As they alone sound the remotest notes on the scale

Of the irretrievable. They have their own

Music. There’s a timbre to the simoom whistling

Through the eye socket of an ankylosaurus skull

No living creature can match; a rustling

Nearly beyond hearing in the feathers-turned-to-stone

Of archaeopteryx; a dim booming hum, bizarre

And regal and queer-comical, to the mastodon

Hung in the warehouse of a glacier, upside down.)

Bea’s encounter with the handsome wounded soldier becomes immediately a bittersweet memory, perfect in every way, transformed into almost generic, uplifting language: she “savors this sensation of having been enlisted in a sweeping modern military enterprise.”

Leithauser gives us this moment in the present tense, an agitated and layered tableau, a moment out of time, a mastodon, massive and complex and frozen. When the soldier exits, the narrative shifts to the past tense, and Bea comes down to earth, as it were, to her family. Papa is warm and kind, a contractor, an Italian immigrant who speaks with an accent though he came to America when he was thirteen. Bea’s sister, Edith, is an amusingly officious little girl who collects paper for the war effort; her brother, Stevie, a kid with terrible eyesight, loudly plays war in the alley. They seem to be a pleasant, typically idiosyncratic family. Until we meet Mama. “Mamma was subject to ‘moods,’ sitting immobile over coffee for hours, staring at the kitchen wall calendar….”

She is, from the moment she appears, a wonderful character, the dark shadowing that lends depth and perspective to Bea’s chaste point of view. Unpleasant, undermining, addicted to candy that she hides all over the house, Mama lurks powerfully through the story and through Bea’s life, by far the most comic character—really the only comic character—and by far the most tragic. Here is our first glimpse, when Bea arrives home from the streetcar:

“I’m home,” Bea said.

“Isaac Lustig is dead,” her mother replied….

The Lustigs lived way up the street. They had moved in only a month or two ago. Bea hadn’t actually laid eyes on any of them yet, but she knew they were Jewish.

“He was a soldier?”

“A student. At Kenyon College in Ohio. Exactly your age, too,” Mamma pointed out. “He drove his car into a tree. He planned to be a doctor.”

“How terrible. The accident was around here?”

“In Ohio.”

“Had you met him?”

Bea’s mother took a moment to answer. “N-no.” Then she added, on a note of funereal triumph, “And now, I never will.”

The balance of Paradiso life is changed suddenly by an incident at a lake, an exposure of nakedness like that other incident in that biblical paradise, another tableau-like scene in which time seems to stand still. The family is at the beach for their annual picnic with Mama’s sister, the beautiful, gentle, and kind Aunt Grace, and her benevolent husband, Dennis, a doctor. The aunt and uncle are revered by Bea. They seem so civilized compared to her own erratic mother and her warm but old-fashioned father. They are revered by Papa, too. Uncle Dennis is his closest friend and most trusted adviser in all things. It is a bright, joyous day and the younger children are splashing and playing in the lake, chasing each other, when Stevie, who is practically blind, throws himself at Aunt Grace thinking she is Edith:

It all happened with such suddenness, Bea could make sense of it only later….

When Aunt Grace rose to her feet, the sight was so very strange that, for just a fraction of a second, Bea couldn’t isolate its strangeness. The top of Aunt Grace’s suit had been yanked from her left shoulder. Her ample white breast above her blue suit was bared for anyone in the world to ogle. The big shocking nipple was dark as a plum.

Papa is wading a few feet away, holding a hand bandaged from an accident at work above the water:

Now both his hands, the normal, bare hand and the bandaged hand, lunged forward, toward her. Oh, he meant to shelter his poor sister-in-law—shield her from the leering, squalid gazes of a beach full of strangers! But his hands halted. They did not quite touch her.

Only a moment’s duration—this surreal little tableau lasted only a moment.

It lasts only a moment, but it is vivid enough to change their lives. Mama goes off the rails, convinced that her husband has always loved Aunt Grace, and makes any further contact between the two families impossible. It is a painful change for Bea, and a shock, at a time when her girlish romantic notions of love are just beginning to run into the reality of adult, physical attraction, for at her art school, Bea meets Ronny, a fellow student, more talented than she is, and far more worldly. He

was not merely extremely handsome but handsome in a fashion guaranteed to fire up Bea’s imagination. He looked intensely literary—meaning not so much that he read books as that he belonged in one. She’s come across him before, somewhere in her constant novel reading. But which one was he—this pale, tall, dark-haired young man who wore a beautiful camel’s hair sports coat and a tawny suede hat? (Not many young men could have gotten away with that hat.) Some disguised prince in exile? Some nineteenth-century consumptive poet on a final pilgrimage?

Ronny is very rich, his mother a great beauty Bea recognizes from the society pages of the newspaper, but even his family has sorrow skulking beneath the cultivated small talk and elegant clothes. Some of that sadness centers on Ronny, a boy with a weak heart and a dreamy nature who cannot please his macho father. The two idealistic young people often argue about art—is it enough in wartime to “paint a peony, a pack of playing cards, a guttered candle”? Ronny, the aesthete, thinks it is more than enough, but Bea experiences still-life painting as almost a betrayal in this time of violent battles overseas.

Her need to feel useful is met when she is asked, like Leithauser’s mother-in-law in real life, to sketch wounded soldiers in the hospital. These portraits—both the drawings Leithauser skatters through the book and his own descriptions of young men joking and winking and bumming cigarettes from the nurses in an attempt to overlook their missing limbs or shattered skulls—are tender and unexpectedly lovely. In style, the drawings and the prose are from another era, a little brash, colloquial, cocky. Again, Leithauser is not so much describing a wounded World War II soldier as describing a World War II vision of one of the brave wounded boys. Any irony or perspective afforded by hindsight is relinquished. Rather than viewing the past critically or analytically, Leithauser embraces its view of itself, a different kind of imagination for a writer who devoted all of A Few Corrections to uncovering the lies of a rosy account of the past.

There is great beauty and dignity in Leithauser’s description of Detroit, noble in the purpose of its fiery factories. There is a sense of both the fullness and the waste of a life as Bea grows up and relinquishes her artistic ambitions, as her family finds and loses its way, as her city sprawls into suburbs and so disappears. There is some sentimentality, too. But Brad Leithauser is not afraid of sentimentality. As he wrote in Darlington’s Fall, when an old professor refers, in front of Russell Darlington, to butterflies and their brief lives devoted to mating as being “fucking machines,”

…Why mar and muddy everything?

Russ was sentimental? Perhaps, but wasn’t it far worse

To go through life without some touchstone

Of the sacred—nothing to hold off the disintegration

Of everything that’s decent? No, by every means

At his disposal Darlington intended to cling

To the quaint notion that our Universe

Admits a few objects without flaw or stain.

Butterflies, say. Or a sweet girl, barely in her teens.

This Issue

March 11, 2010